172nd Tunnelling Company

The 172nd Tunnelling Company was one of the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers created by the British Army during World War I. The tunnelling units were occupied in offensive and defensive mining involving the placing and maintaining of mines under enemy lines, as well as other underground work such as the construction of deep dugouts for troop accommodation, the digging of subways, saps (a narrow trench dug to approach enemy trenches), cable trenches and underground chambers for signals and medical services.[1]

| 172nd Tunnelling Company | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | World War I |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Royal Engineer tunnelling company |

| Role | military engineering, tunnel warfare |

| Nickname(s) | "The Moles" |

| Engagements | World War I The Bluff Vimy Ridge |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | William Henry Johnston VC William Clay Hepburn |

Background

By January 1915 it had become evident to the BEF at the Western Front that the Germans were mining to a planned system. As the British had failed to develop suitable counter-tactics or underground listening devices before the war, field marshals French and Kitchener agreed to investigate the suitability of forming British mining units.[2] Following consultations between the Engineer-in-Chief of the BEF, Brigadier George Fowke, and the mining specialist John Norton-Griffiths, the War Office formally approved the tunnelling company scheme on 19 February 1915.[2]

Norton-Griffiths ensured that tunnelling companies numbers 170 to 177 were ready for deployment in mid-February 1915.[3] In the spring of that year, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and The Bluff which required the deployment of new drafts of tunnellers for several months after the formation of the first eight companies. The lack of suitably experienced men led to some tunnelling companies starting work later than others. The number of units available to the BEF was also restricted by the need to provide effective counter-measures to the German mining activities.[4] To make the tunnels safer and quicker to deploy, the British Army enlisted experienced coal miners, many outside their nominal recruitment policy. The first nine companies, numbers 170 to 178, were each commanded by a regular Royal Engineers officer. These companies each comprised 5 officers and 269 sappers; they were aided by additional infantrymen who were temporarily attached to the tunnellers as required, which almost doubled their numbers.[2] The success of the first tunnelling companies formed under Norton-Griffiths' command led to mining being made a separate branch of the Engineer-in-Chief's office under Major-General S.R. Rice, and the appointment of an 'Inspector of Mines' at the GHQ Saint-Omer office of the Engineer-in-Chief.[2] A second group of tunnelling companies were formed from Welsh miners from the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the Monmouthshire Regiment, who were attached to the 1st Northumberland Field Company of the Royal Engineers, which was a Territorial unit.[5] The formation of twelve new tunnelling companies, between July and October 1915, helped to bring more men into action in other parts of the Western Front.[4]

Most tunnelling companies were formed under Norton-Griffiths' leadership during 1915, and one more was added in 1916.[1] On 10 September 1915, the British government sent an appeal to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand to raise tunnelling companies in the Dominions of the British Empire. On 17 September, New Zealand became the first Dominion to agree the formation of a tunnelling unit. The New Zealand Tunnelling Company arrived at Plymouth on 3 February 1916 and was deployed to the Western Front in northern France.[6] A Canadian unit was formed from men on the battlefield, plus two other companies trained in Canada and then shipped to France. Three Australian tunnelling companies were formed by March 1916, resulting in 30 tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers being available by the summer of 1916.[1]

Unit history

172nd Tunnelling Company included a significant number of miners from South Wales, as did the 184th, 170th, 171st, 253rd and 254th Tunnelling Company.[7]

From its formation in April 1915 until the end of the war the company served under First Army south of the Ypres Salient.[3][8]

Ypres Salient

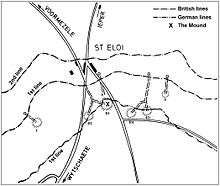

Following its formation, 172nd Tunnelling Company was first employed in the area of St Eloi and The Bluff at Ypres,[1] added to which the 172nd Tunnelling Company was also active at Hill 60.

The Germans held the top of Hill 60 from 16 December 1914 to 17 April 1915, when it was captured briefly by the British 5th Division after the explosion of five mines under the German lines by the Royal Engineers. The early underground war in the area had involved both the 171st and 172nd Tunnelling Company.[9] In July 1915, 175th Tunnelling Company was extended to Hill 60,[1] and 172nd Tunnelling Company focused on The Bluff instead.[1]

The Bluff, located halfway in between Voormezele and Hollebeke, is an artificial ridge in the landscape created by spoil from failed attempts to dig a canal.[10] With the additional height in an otherwise relatively flat landscape, The Bluff was an important military objective.[11] German forces took The Bluff in February 1916.[12] In addition to The Bluff, 172nd Tunnelling Company was also responsible for mining at St Eloi south of Ypres.

At St Eloi, military mining began in early 1915. The Germans had built an extensive system of defensive tunnels and were actively mining at the intermediate levels.[13] In March 1915, they fired mines under the elevated area known as The Mound just south-east of St Eloi[14] and in the ensuing fighting (the Action of St Eloi,[15] 14–15 March 1915) the British infantry suffered some 500 casualties. A month later, on 14 April 1915, the Germans fired another mine producing a crater over 20 metres (66 ft) in diameter. After these experiences, the British started an extensive programme of defensive mining at St Eloi to protect the British trenches from future German mines, but also included offensive elements by placing large attack mines beneath the German trenches. Much of this work was done by the 177th Tunnelling Company and the 172nd Tunnelling Company, the latter commanded in early 1915 by Captain William Henry Johnston VC.[14] Johnston left 172nd Tunnelling Company in early May, when he was succeeded as officer commanding by William Clay Hepburn, a Territorial Army Captain in the Monmouthshire Regiment. Hepburn was a mining engineer and colliery agent in civilian life, and the first non-regular Royal Engineer officer to command a Tunnelling Company.[16] The officer in charge of 172nd Tunnelling Company's offensive mining activities at St Eloi was Lieutenant Horace Hickling, who would go on to command 183rd Tunnelling Company on the Somme in 1916,[17] supported by Lieutenant Frederick Mulqueen, who would go on to command 182nd Tunnelling Company at Vimy in 1917.[18] The geology of the Ypres Salient featured a characteristic layer of sandy clay, which put very heavy pressures of water and wet sand on the underground works and made deep mining extremely difficult. In autumn of 1915, 172nd Tunnelling Company managed to sink shafts through the sandy clay at a depth of 7.0 metres (23 ft) down to dry blue clay at a depth of 13 metres (43 ft), which was ideal for tunneling, from where they continued to drive galleries towards the German lines at a depth of 18 metres (60 ft).[19] This constituted a major achievement in mining technique and gave the Royal Engineers a significant advantage over their German counterparts.

Meanwhile, at The Bluff, mining was continued by the 172nd Tunnelling Company and in November 1915, John Norton-Griffiths proposed to sink 20 or 30 shafts, about 46–64 metres (50–70 yd) apart, into the blue clay from St Eloi to The Bluff. On 21 January 1916, German miners blew several large charges at The Bluff, which caused 172nd Tunnelling Company to halt its work on the shallow galleries in St Eloi in order to complete the deep mines as soon as possible. On 14 February, the German infantry succeeded in capturing The Bluff from the British and advanced towards St Eloi, raising fears that the British deep mines might be captured before they could be fired.[19]

The British decided to use the deep mines created by 172nd Tunnelling Company at St Eloi in a local operation (the Battle of St Eloi Craters, 27 March – 16 April 1916) and six charges were prepared.[20][14] There were four central mines, of which two were laid from shaft D and two from shaft H. The largest, code-named D1, contained 14,000 kilograms (31,000 lb) of ammonal and was placed beneath The Mound, while the mines code-named D2, H1 and H4 were charged with between 5,400 kilograms (12,000 lb) and 6,800 kilograms (15,000 lb). The two flanking mines, code-named I and F, were significantly smaller charges laid short of the German front line. For most of the time, the British preparations were severely obstructed by highly efficient German counter-mining.[21] When the mines were fired at 4.15 a.m. on 27 March 1916, D1 and D2 were detonated first, followed by H1 and H4, then I and finally F. To witnesses it "appeared as if a long village was being lifted through flames into the air" and "there was an earth shake but no roar of explosion".[22] The detonation obliterated The Mound and killed or buried some 300 men of the 18th Reserve Jäger Battalion;[23] two miles away, at Hill 60, the trenches rocked and heaved.[22] The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers attacked and held the D1, D2 and F craters, but efforts to dig communications trenches to their positions failed under the heavy German fire, the muddy ground and debris thrown up by the explosions. British attempts to gain a line beyond the craters were unsuccessful for a week but eventually took the four central craters in the early morning of 3 April, shortly before the 3rd Division was relieved by the 2nd Canadian Division. A German counter-attack during the night of 5 April captured the craters, and the Canadians were ordered to withdraw. The operation had been a failure and the advantage of the mines had been lost; the problem lay in the problem of integrating mines into the attack and the Allied inability to hold crater positions after they had been captured.[24] It also demonstrated that holding a crater against concentrated fire and determined German counterattack was extremely difficult.[25]

In March 1916, 172nd Tunnelling Company handed its work at St Eloi over to 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company.[26] It then relieved 181st Tunnelling Company in the Rue du Bois area, but soon moved back to The Bluff.[1]

Vimy sector

In April 1916, the 172nd Tunnelling Company was relieved at The Bluff by 2nd Canadian Tunnelling Company and moved to Neuville-Saint-Vaast near Vimy in northern France,[1] where it was deployed alongside 176th Tunnelling Company, which had moved to Neuville-Saint-Vaast in April 1916 and remained there for a considerable time.[1] The front sectors at Vimy and Arras, where extremely heavy fighting between the French and the Germans had taken place during 1915, were taken over by the British in March 1916.[18] Vimy, in particular, was an area of busy underground activity. From spring 1916, the British had deployed five tunnelling companies along the Vimy Ridge, and during the first two months of their tenure in the area, 70 mines were fired, mostly by the Germans.[18] Between October 1915 and April 1917 an estimated 150 French, British and German charges were fired in this 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) sector of the Western Front.[27]

Neuville-Saint-Vaast was close to the German "Labyrinth" stronghold between Arras and Vimy and not far from Notre Dame de Lorette.[6] British tunnellers progressively took over work on the shafts in the area from the French between February and May 1916.[27] As part of this process, the New Zealand Tunnelling Company took over a sector between Roclincourt and Écurie from the French 7/1 compagnie d'ingénieurs territoriaux during March 1916. On 29 March 1916, the New Zealanders exchanged position with the 185th Tunnelling Company and moved to Roclincourt-Chantecler, a kilometre south of their old sector.[6] 172nd Tunnelling Company seems to have shared the Neuville-Saint-Vaast sector with the 176th and 185th Tunnelling Company until it was relieved there in May 1916 by the 2nd Australian Tunnelling Company.[1] Also in May 1916, a German infantry attack, which forced the British back 640 metres (700 yd), was aimed at neutralising British mining activity by capturing the shaft entrances. From June 1916, however, the Germans withdrew many miners to work on the Hindenburg Line and also for work in coal mines in Germany. In the second half of 1916 the British constructed strong defensive underground positions, and from August 1916, the Royal Engineers developed a mining scheme to support a large-scale infantry attack on the Vimy Ridge proposed for autumn 1916, although this was subsequently postponed.[18] After September 1916, when the Royal Engineers had completed their network of defensive galleries along most of the front line, offensive mining largely ceased[27] although activities continued until 1917. The British gallery network beneath Vimy Ridge eventually grew to a length of 12 kilometres (7.5 mi).[27]

172nd Tunnelling Company stayed near Vimy and remained active in the area in preparation for the Battle of Vimy Ridge (9–12 April 1917), together with 175th and 182nd Tunnelling Companies.[27] 184th Tunnelling Company and 255th Tunnelling Company also served a tenure at Vimy. The Canadian Corps was posted to the northern part of Vimy Ridge in October 1916 and preparations for an attack were revived in February 1917.[18] Prior to the Battle of Vimy Ridge, the British tunnelling companies secretly laid a series of explosive charges under German positions in an effort to destroy surface fortifications before the assault.[28] The original plan had called for 17 mines and 9 Wombat charges to support the infantry attack, of which 13 (possibly 14) mines and 8 Wombat charges were eventually laid.[27] At the same time, 19 crater groups existed along this section of the Western Front, each with several large craters.[29] In order to assess the consequences of infantry having to advance across cratered ground after a mining attack, officers from the Canadian Corps visited La Boisselle and Fricourt where the mines on the first day of the Somme had been blown. Their reports and the experience of the Canadians at St Eloi in April 1916 – where mines had so altered and damaged the landscape as to render occupation of the mine craters by the infantry all but impossible –, led to the decision to remove offensive mining from the central sector allocated to the Canadian Corps at Vimy Ridge. Further British mines in the area were vetoed following the blowing by the Germans on 23 March 1917 of nine craters along no man's land as it was probable that the Germans were aiming to restrict an Allied attack to predictable points. The three mines already laid by 172nd Tunnelling Company were also dropped from the British plans. They were left in place after the assault and were only removed in the 1990s.[30] Another mine, prepared by 176th Tunnelling Company against the German strongpoint known as the Pimple, was not completed in time for the attack. The gallery had been pushed silently through the clay, avoiding the sandy and chalky layers of the Vimy Ridge, but by 9 April 1917 was still 21 metres (70 ft) short of its target.[31] In the end, two mines were blown before the attack, while three mines and two Wombat charges were fired to support the attack,[27] including those forming a northern flank.[32]

In early 1918 half of 252nd Tunnelling Company, arriving in the Vimy Ridge sector from Beaumont-Hamel, was attached to 172nd Tunnelling Company.[27]

Somme sector

March 1918 saw 172nd Tunnelling Company working on a new defensive line on the Somme, near Bray-Saint-Christophe. It fought as emergency infantry near Villecholles, where it carried out a fighting retreat.[1]

Memorial

On a small square in the centre of Sint-Elooi stands the 'Monument to the St Eloi Tunnellers' which was unveiled on 11 November 2001. The brick plinth bears transparent plaques with details of the mining activities by 172nd Tunnelling Company and an extract from the poem Trenches: St Eloi by the war poet T.E. Hulme (1883–1917). There is a flagpole with the British flag next to it, and in 2003 an artillery gun was added to the memorial.[33]

Notable people

- Captain William Henry Johnston VC commanded 172nd Tunnelling Company at St Eloi in early 1915, at a time when the Germans exploded mines under the area known as The Mound just south-east of St Eloi. Johnston had won the Victoria Cross on 14 September 1914 during the Race to the Sea at Missy in France. He was killed in the Ypres Salient on 8 June 1915.[14]

- William Hackett enlisted in the British Army on 25 October 1915, after having been rejected three times by the York and Lancaster Regiment for being too old and having been diagnosed with a heart condition. He spent two weeks of basic training at Chatham, joining 172nd Tunnelling Company.[34] He later served with 254th Tunnelling Company. He was 43 years old and a Sapper when he performed a deed for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross on 22 June/23 June 1916 at Shaftesbury Avenue Mine, near Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée, France.

See also

- Mine warfare

References

- An overview of the history of 172nd Tunnelling Company is also available in Robert K. Johns, Battle Beneath the Trenches: The Cornish Miners of 251 Tunnelling Company RE, Pen & Sword Military 2015 (ISBN 978-1473827004), p. 215 see online

- A detailed account of 172nd Tunnelling Company's activities at St Eloi and The Bluff: see online

- The Tunnelling Companies RE Archived May 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, access date 25 April 2015

- "Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths (1871–1930)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Watson & Rinaldi, p. 49.

- Peter Barton/Peter Doyle/Johan Vandewalle, Beneath Flanders Fields - The Tunnellers' War 1914-1918, Staplehurst (Spellmount) (978-1862272378) p. 165.

- "Corps History – Part 14: The Corps and the First World War (1914–18)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Anthony Byledbal, "New Zealand Tunnelling Company: Chronology" (online Archived July 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine), access date 5 July 2015

- Ritchie Wood, Miners at War 1914-1919: South Wales Miners in the Tunneling Companies on the Western Front, Wolverhampton Military Studies, Solihull (Helion and Company) 2016, ISBN 978-1911096498.

- Watson & Rinaldi, p. 19.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 247.

- Karel, Roose (2003-02-03). "Cycling Belgium's Waterways: Comines-Ieper". Gamber Net Home. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Baker, Chris. "Fighting at the Bluff". The Long, Long Trail. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- "CWGC: Cemetery Details". Information on the burial places of Commonwealth soldiers, sailors and air crew. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Jones 2010, p. 101.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 248.

- "Action of St. Eloi". theactionofsteloi1915.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- Jones 2010, p. 79.

- Jones 2010, p. 130.

- Jones 2010, p. 133.

- Jones 2010, pp. 101-103.

- "St Eloi Craters". firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- Jones 2010, pp. 104-105.

- Jones 2010, p. 106.

- Jones 2010, p. 137.

- Jones 2010, p. 107-109.

- Jones 2010, p. 100.

- Jones 2010, p. 146.

- The Durand Group: Vimy Ridge online, access date 2016-08-03

- Boire (1992) pp. 22–23

- Boire (1992) p. 20

- Jones 2010, pp. 134-135.

- Jones 2010, p. 136.

- Jones 2010, p. 135.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 184.

- "Tunnelling in the First World War". tunnellersmemorial.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-23. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

Further reading

- Ritchie Wood. Miners at War 1914-1919: South Wales Miners in the Tunneling Companies on the Western Front. ISBN 978-1-91109-649-8.

- Alexander Barrie. War Underground – The Tunnellers of the Great War. ISBN 1-871085-00-4.

- The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914–1919, – MILITARY MINING.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arthur Stockwin (ed.), Thirty-odd Feet Below Belgium: An Affair of Letters in the Great War 1915-1916, Parapress (2005), ISBN 978-1-89859-480-2 (online).

- Holt, Tonie; Holt, Valmai (2014) [1997]. Major & Mrs Holt's Battlefield Guide to the Ypres Salient & Passchendaele. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-0-85052-551-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graham E. Watson & Richard A. Rinaldi, The Corps of Royal Engineers: Organization and Units 1889–2018, Tiger Lily Books, 2018, ISBN 978-171790180-4.