Battle of Dinant

The Battle of Dinant was an engagement fought by French and German forces in and around the Belgian town of Dinant in the First World War, during the German invasion of Belgium. The French Fifth Army and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) advanced into Belgium and fought the Battle of Charleroi (21–23 August) and Battle of Mons (23 August), from the Meuse crossings in the east, to Mons in the west. On 15 August 1914, German troops captured the Citadel of Dinant which overlooked the town; the citadel was recaptured by a French counter-attack during the afternoon. French troops spent the next few days fortifying the Meuse crossings and exchanging fire with German troops on the east bank.

A German raiding-party drove into Dinant on the night of 21/22 August but the attack degenerated into a fiasco, in which Germans may have fired at each other. Rather than assume that the small-arms fire had come from the French on the west bank, the Germans blamed Belgian civilians, killing seven and burning down 15 to 20 houses in reprisal. The raiders ran away, with 19 dead and 117 wounded. On 23 August, the Germans attacked Dinant again, under the impression that the town was full of francs-tireurs (free shooters; terrorists to the Germans) and massacred 674 unarmed Belgian civilians, while fighting the French, who were dug in along the west bank and on the east end of the bridge. The massacre was a systematic attack on assumed civilian resisters and was the largest German atrocity perpetrated during the invasion, which became known as The Rape of Belgium.

Background

In 1914, the town had a population of 7,000 people and was an important strategic crossing on the Meuse, where the river flows through a south–north gorge. Three roads and a path converged on the town from the east, over an escarpment and down into the town, along which an attack from the east would come. The wooded ridge on the east bank was topped by the Napoleonic era stone Citadel of Dinant overlooking the town and the Meuse bridge, 100 m (330 ft) below.[1] In 1914 there was a ribbon of streets about 4 km (2.5 mi) long on the east bank, a few hundred metres wide.[2] Before the battle, the Mayor of Dinant urged the population to not take part in the fighting and forbade manifestations in support of the Allies.[3]

Prelude

6–14 August

The initial operations in the German invasion of France began with the Occupation of Luxembourg and the invasion of Belgium on 4 August. Five German infantry brigades, three cavalry divisions with horse artillery and machine-gun detachments and ten Jäger battalions crossed the Belgian border. The 5th Cavalry Division and the Guard Cavalry Division advanced through Luxembourg and entered Belgium on 10 August, with orders to advance 60 km (37 mi) north-west to Dinant and then scout the Meuse as far as the French border near Givet.[4] The town of Dinant was close to the French border, between Liège and Mons on the east bank of the Meuse.[1] On 6 August, Belgian engineers dispersed a patrol of German hussars at Anseremme and on 12 August, French infantry at Dinant destroyed a cavalry patrol. By 14 August, the French Fifth Army had occupied Dinant and the west bank of the Meuse with two divisions and next day, the main force of the German 3rd Army (Colonel-General Max von Hausen) arrived.[5]

15 August

.jpg)

On 15 August, troops of the German 3rd and 4th Cavalry divisions, five battalions of Jäger and three field artillery groups, attempted to take Dinant by coup de main.[6] The French I Corps held the west bank of the Meuse and at Dinant, the 2nd Division (Général de division Henry Victor Deligny) had a battalion of the 33rd Infantry Regiment, two companies of the 148th Infantry Regiment (detached from the 4th Division) and a section of machine-guns in the citadel and in the exits from Dinant, towards the St. Nicolas and Leffe suburbs. At 6:00 a.m., German cavalry guarded the flanks as the 12th Freyberg Jäger Battalion and the 13th Garde-Jäger Battalion supported by horse artillery and machine-guns, attacked the town and citadel.[5] The Germans got a machine-gun into the citadel around 11:45 a.m. and the French retreated through a small stairway along the cliff, having had 50 percent casualties. Jäger descended the stairway and advanced into the town by 1:30 p.m.[7]

The French, with no artillery, were forced out of the citadel and then back over the bridge to the west bank. Parties of Jäger crossed the bridge in pursuit, as Germans on the high ground on the east bank and in the citadel, engaged the French at the end of the bridge with machine-gun fire.[7] The French retired to the slopes on the west bank, where there was good cover and towards 2:00 p.m., French artillery were heard, as the 8th and 73rd Infantry regiments counter-attacked down the slope with great determination. The Jäger were forced back across the Meuse and by 5:00 p.m., the French had climbed the 408 stairs to the citadel and retaken it. The Germans withdrew from the town and the heights with their prisoners, towards the main body of the 3rd Army. During the battle, the French Cavalry Corps (Général de Corps d’Armée A. Sordet), attempted to attack the German flank on the east bank but was held up by German infantry.[8] The French retired to the west bank having lost 1,100 casualties and occupied the bridge and houses nearby.[6] Two battalions of the 148th Infantry Regiment in Leffe and St. Nicolas also retired to the west bank. In Dinant a civilian had been killed, one had been wounded and the hospital and houses on the east bank had been hit by shells.[7]

16–21 August

On 16 August the French fortified the west bank of the Meuse at Dinant. The bridge was blocked with barbed-wire entanglements and the streets near the river were barricaded. The railway station and the level crossing on the Dinant–Onhaye road were garrisoned and the Hotel de la Poste and houses along the Meuse were loopholed to command the riverbanks, bridge and the approach roads. On the east bank the French built barricades and put up barbed-wire in front of the bridge-piers and near the church.[9] From 15–22 August, skirmishing took place between the Germans on the hills on the east bank and French patrols. Some German detachments conveyed in motor vehicles armed with machine-guns, attacked houses in the neighbourhood of Dinant and several inhabitants of Houx were killed and the village sacked and burnt down.[10] On 20 August, the infantry divisions of the 3rd Army closed up to the cavalry divisions east of Dinant. By 21 August, four of the six divisions of the German 3rd Army intended to cross the Meuse, had arrived but the heavy artillery was a day away, yet an attack by frontal assault had been ordered by the German Chief of the General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, for 23 August.[11] Hausen ordered XII Corps (General Karl Ludwig d'Elsa) and the XIX Corps (General Maximilian von Laffert) to advance on the town and artillery began to bombard Dinant, preparatory to the attack. Barges and pontoon bridges were gathered in anticipation of the French blowing the Meuse bridges.[12]

Night raid, 21/22 August

A German raiding party mounted in motor vehicles attacked Dinant in the night of 21/22 August. German infantry and pioneers advanced from Ciney along the central road into Dinant, killed seven civilians and burned 15–20 houses. Members of the reconnaissance force claimed later that civilians had attacked them and civilians thought that it had been an attack by drunken soldiers.[2] A German soldier wrote later that they had been ordered to

... kill everyone and wipe off the map one part on the left bank [sic] of the Meuse!!! It was a tremendously (kolossal) honourable task and if successful, it would be famous for all time.

— Private Kurt Rasch[2]

The party moved along rue Saint-Jacques in the dark and threw a hand grenade into a café, at which gunfire was opened; the party panicked and ran off, leaving 19 dead and 117 wounded. The foremost troops had reached the Meuse, where they were fired on from all sides; in the panic, Germans may have shot at each other but claimed later that revolvers and shotguns had been used by civilians (no survivors admitted to taking up arms). French soldiers held the bridge over the Meuse and had patrols in the town, which may have engaged the Germans in the rue Saint-Jacques and probably fired on the Germans at the river. In the aftermath the Germans took Dinant to be full of hostile civilians.[2]

Massacres, 23 August

At 4:50 a.m. on 23 August, in a thick fog, 57 German artillery batteries began to bombard Dinant. Most of the 40th Division was sent south to Givet and Fumay, thence to cross the Meuse and attack the right flank of the Fifth Army, which reduced the attack on Dinant to XII Corps.[13] The 32nd Division (Major-General Horst von der Planitz) and the 23rd Reserve Division (Major-General Alexander von Larisch) crossed the Meuse on barges and pontoons at Leffe, north of the town and the 23rd Division (Major-General Karl von Lindemann) crossed to the south at Les Rivages.[2]

The French I Corps had been moved north-west to reinforce X Corps (General Gilbert Desforges) at Arsimont, having been relieved by the 51st Reserve Division (Général de division René Boutegourd) and two brigades of the 2nd Division.[2] Four columns of the German 46th Infantry Brigade of the 23rd Division advanced into Dinant, against a regiment of the 51st Reserve Division and (allegedly) Belgian irregulars.[14] The northern column entered Leffe and the hamlet of Devant-Bouvignes, as two columns advanced into the Dinant town centre, along rue Saint-Jacques and a road down into Faubourg Saint-Nicolas and the Place d'Armes. The southern column attacked along the Froidvau road into Les Rivages. French troops on the west bank engaged the Germans with small-arms fire and artillery; the French also held both ends of the principal Dinant bridge and some advanced posts in the town centre.[2]

Leffe was overlooked by Leffe Abbey and its brewery and as Infantry Regiment 178 (IR 178) and Infantry Regiment 103 (IR 103) advanced into the area, they thought that civilians fired on them as well as the French from Bouvignes-sur-Meuse on the west bank. Three civilians were shot at the riverbank where they had fled from the soldiers, who later admitted that they had no idea if the victims had taken up arms. The 3rd Company of IR 178 was ordered to clear Leffe of francs-tireurs, who had supposedly fired at the Germans from a saw-mill.[15] Infantry Regiment 108 (IR 108) and Infantry Regiment 182 (IR 182), accompanied by artillery moved along rue Saint Jacques into the town just north of the bridge, where they were fired on by the French. The Germans killed male civilians during the day and at 5:30 p.m., 27 men were shot by IR 108 in the rue des Tanneries. The German troops barricaded streets with furniture and soldiers from IR 182 captured a man on suspicion of firing at them, although he was unarmed and tied him to a barricade as a human shield. When German artillery mistakenly bombarded the force, the man was shot before the Germans withdrew.[16]

German troops set fire to houses and by late afternoon the area was on fire; in Leffe and Saint-Jacques 312 civilians had been killed by the Germans. Near the town centre, Grenadier Regiment 100 (GR 100) entered Faubourg Saint-Nicolas, where they were fired on by French troops. The Germans had anticipated attacks by civilians, moved forward in two columns and each time they reached a door they stopped, fired through windows and threw bombs into the cellars. To cross the Place d'Armes, which was visible to the French across the river, the Germans used civilians as a human shield. Dinantais forced from houses were held at an iron works and the prison in the Place d'Armes. German soldiers on high ground outside the town fired on civilians in the prison courtyard for a time. In the late afternoon, 19 men at the ironworks were shot; the rest were taken to the Place d'Armes, being made to shout, "Long live Germany! Long live the Kaiser!" along the way. Soldiers of GR 100 separated 137 men, lined them up against a garden wall and shot them, on the orders of Lieutenant-Colonel von Kielmannsegg, the I Battalion commander.[17][lower-alpha 1]

Grenadier Regiment 101 and the 3rd Pioneer Company entered Les Rivages during the afternoon, to build a pontoon bridge over the Meuse. The right bank narrows to a defile between the escarpment and the river, with only a road and one line of dwellings. The area was particularly exposed to French fire but for an hour no resistance was encountered. Houses were searched, hostages were taken and 40 m (44 yd) of the bridge assembled. At about 5:00 p.m. several Germans working on the bridge were shot and killed and German soldiers later claimed that the gunfire came from francs-tireurs on both sides of the river, while Belgian civilians said the bullets came from the French on the west bank. Some inhabitants of Dinant cheered the success of the French and the cliffs nearby created echoes, which made it difficult to judge the direction of fire. The unusual acoustics contributed to the German belief that they were attacked from behind by civilians, while they were being engaged by the French from Bourdon on the west bank.[19]

A local magistrate was sent across the river to warn francs-tireurs that the hostages would be shot if the firing continued. The magistrate returned, having been shot and wounded by the Germans on the way and said that only French soldiers were firing. After more gunfire, civilians were lined up against a wall and shot. Of the 77 victims, seven were men over 70, 38 were women or girls and 15 were children under 14 (seven being babies).[20] When the Grenadiers reached the west bank, they killed 86 civilians in Neffe; 23 civilians found hiding under a railway viaduct were shot and 43 were taken to the east bank and shot there.[21] German attacks between Houx and Dinant were repulsed but the Germans got across the Meuse at Hastierès and pushed the 51st Division reservists back 2 km (1.2 mi) to Onhaye. Boutegourd called on I Corps for reinforcements and d'Esperey ordered the corps to reverse direction. Two battalions of the 8th Infantry Brigade were in reserve with an attached cavalry regiment and d'Esperey ordered the commander, Charles Mangin to rush to Dinant. The reinforcements met the remnants of the 51st Reserve Division, made a bayonet charge towards Onhaye, on the Philippeville road and established a blocking position east of Onhaye. With the 51st Reserve Division to the north, the 8th Infantry Brigade restricted the Germans to a bridgehead from Onhaye to Anhée.[22][23][24] Next day the French I Corps arrived from the Sambre to Dinant and contained the 3rd Army in bridgeheads on the west bank of the Meuse, as the Fifth Army retreated from the angle of the Sambre and Meuse rivers.[25]

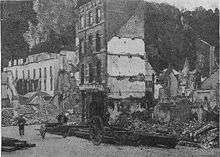

Aftermath

24 August

On 24 August, the area of Dinant south of the bridge, which had not been attacked on 23 August, was systematically burned down by the Germans.[20] Dinant was looted and German troops destroyed public and historic buildings, including the collegial church and the town hall. When IR 178 crossed the Meuse to Bouvignes, 31 villagers were killed and south of Dinant at Hastière-par-delà and Hastière-Lavaux, civilians were caught between Infantry Regiment 104 and Infantry Regiment 133 as they tried to cross the Meuse and French troops on the west bank. The Germans claimed that the civilians helped the French and 19 people, including two ten-year-olds from Hastière-par-delà, were killed and the village burned.[21] By 24 August, when the German advance resumed, the French had gone.[11][25]

Casualties and commemoration

Fires set by the Germans on the night raid of 21/22 August provoked the flight of 2,500 inhabitants the next day. On 23 August, about 674 civilians were massacred, 1,200 houses were burned down and 400 people were deported to Germany and interned until November. This massacre was the largest of "The Rape of Belgium", which was instrumental in the US involvement in the war.[26] The killings continued on 24 August; houses burned for days and lit up the countryside and a stench of corpses polluted the air as they decomposed in the sun.[20] The Germans lost 1,275 men killed and about 3,000 wounded and the French had about 1,100–1,200 casualties in the fighting around Dinant.[6][26] In the 4th Infantry Brigade (Général de brigade Philippe Pétain), Lieutenant Charles de Gaulle was among the first to be wounded, receiving a bullet in the fibula.[22] On 6 May 2001, Walter Kolbow, a high secretary at the German Ministry of Defence, placed a wreath and bowed before a monument in Dinant to the victims bearing the inscription: To the 674 Dinantais martyrs, innocent victims of German barbarism.[27]

Notes

- The survivors gave evidence recorded by the Belgian Second Commission report. The Tschoffen wall massacre was not committed to punish alleged francs-tireurs, because the soldiers knew the victims were innocent as individuals but perceived them as collectively responsible for the actions of supposed francs-tireurs. When people asked the guards why they had been assembled in the iron works; "Some said it was for our own safety. Others said we were to be executed for shooting".[18]

Footnotes

- Herwig 2009, p. 162.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, p. 46.

- Lipkes 2007, p. 257.

- Brose 2001, p. 185.

- Brose 2001, pp. 190–191.

- Tyng 2007, p. 76.

- Essen 1917, p. 143.

- Spears 1999, p. 53.

- Essen 1917, p. 156.

- Essen 1917, p. 144.

- Brose 2001, pp. 199–200.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, p. 45.

- Herwig 2009, p. 164.

- Herwig 2009, pp. 164–165.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, pp. 46–47.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, p. 47.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, p. 48.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, pp. 49–50.

- Francois & Vesentini 2000, pp. 51–82.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, pp. 50–51.

- Horne & Kramer 2001, p. 52.

- Herwig 2009, pp. 166, 168.

- Spears 1999, p. 158.

- Tyng 2007, p. 115.

- Doughty 2005, p. 74.

- Herwig 2009, p. 168.

- Emsley 2003, p. 28.

References

Books

- Brose, E. D. (2001). The Kaiser's Army: The Politics of Military Technology in Germany during the Machine Age, 1870–1918. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517945-3.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Emsley, C. (2003). War, Culture and Memory. Milton Keynes: The Open University. ISBN 978-0-7492-9611-7.

- Essen, L. J. van der (1917). The Invasion and the War in Belgium From Liège to the Yser. London: T. F. Unwin. OCLC 800487618. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- Horne, J. N.; Kramer, A. (2001). German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08975-2.

- Lipkes, J. (2007). Rehearsals. The German Army in Belgium August 1914. Leuven: Leuven University Press. ISBN 978-3-515-09159-6.

- Spears, E. (1999) [1968]. Liaison 1914 (2nd Cassell, repr. ed.). London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 978-0-304-35228-9.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme Publishing ed.). New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-1-59416-042-4.

Journals

- Francois, A.; Vesentini, Frédéric (2000). "Essai sur l'origine des massacres du mois d'août 1914 à Tamines et à Dinant" [Essay on the Origin of the Massacres of August 1914 at Tamines and Dinant]. Cahiers d'histoire du temps présent (in French) (7). ISSN 0769-4504.