Action of 25 September 1917

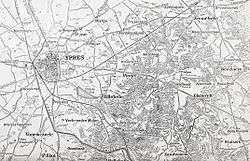

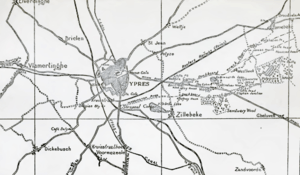

The Action of 25 September 1917 was a German methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) which took place during the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July – 10 November) on the Western Front during the First World War. On the front of the British X Corps (Lieutenant-General Thomas Morland) at the south-east side of the Gheluvelt Plateau, two regiments of the German 50th Reserve Division attacked on both sides of the Reutelbeek stream, on a 1,800 yd (1,600 m) front. The Gegenangriff was supported by German aircraft and 44 field and 20 heavy batteries of artillery, four times the usual amount of artillery for a German division.

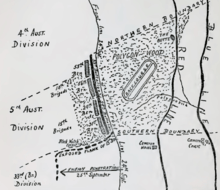

The German infantry managed to advance for about 100 yd (91 m) near the Menin road on the southern flank and 600 yd (550 m) on the northern flank beyond the Reutelbeek, close to Black Watch Corner. The attack was supported by artillery-observation aircraft, ground-attack aircraft and a box-barrage fired behind the British front-line, which isolated the British defenders from reinforcements and cut off the supply of ammunition. Return-fire from the 33rd Division south of Polygon Wood and the 15th Australian Brigade of the 5th Australian Division along the southern edge of the wood forced the attackers under cover. German parties re-captured several pillboxes of the Wilhelmstellung near Black Watch Corner, which had fallen to the British during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge (20 September) but attempts to reinforce the attackers failed.

General Herbert Plumer, the commander of the Second Army, ordered the attack scheduled for 26 September to go ahead but modified the objectives of the 33rd Division. The 98th Brigade was to advance and cover the right flank of the 5th Australian Division and the 100th Brigade to the south was to re-capture the lost ground. The depleted 98th Brigade was delayed and only managed to reach Black Watch Corner, 1,000 yd (910 m) short of its objectives. Reinforcements moved forward into the 5th Australian Division area to the north and attacked south-westwards at noon, combined with a frontal attack from Black Watch Corner. By 2:00 p.m. the attack had succeeded despite massed machine-gun fire; later in the afternoon, the 100th Brigade re-took the lost ground north of the Menin road. Casualties in the 33rd Division were so great that it was relieved on 27 September by the 23rd Division.

Background

Strategic developments

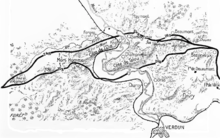

The failure of the Kerensky Offensive in Russia in July had hastened the disintegration of the Russian army, the possibility of a Russian armistice and a huge reinforcement of the German Western Front. From 15 to 25 August, the Battle of Hill 70 was fought against the 6th Army by the Canadian Corps and forestalled the transfer of divisions to Flanders. On 20 August, the French attacked the German 5th Army at Verdun and in four days captured much of the remaining ground lost to the Germans in 1916 and took 9,500 prisoners, thirty guns, 100 trench mortars and 242 machine-guns.[1] The Germans were not able to mount big counter-attacks, because their specialist counter-attack divisions (Eingreif divisions Eingreifdivisionen) had been transferred to Flanders.[2] French preparations continued for an offensive on the Chemin des Dames (the Battle of La Malmaison) in October and the British Third Army planned a surprise artillery and tank attack (the Battle of Cambrai) on the Flesquières Salient. France was running short of manpower; at the end of September, the French Minister of War had been told that another defeat could provoke more mutinies, which would be terminal for the French war effort. The British General Headquarters (GHQ) of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) feared that the French might be forced into a separate peace.[3]

Tactical developments

GHQ quickly studied the results of the attack of 31 July (the Battle of Pilckem Ridge) and on 7 August, sent questions to the Fifth Army headquarters about the new conditions produced by German defence-in-depth. The German 4th Army had spread strong points and pillboxes in the areas between its defensive lines and made rapid counter-attacks with local reserves and Eingreif divisions against Allied penetrations.[4][lower-alpha 1] At the end of August, Haig moved the Fifth Army–Second Army boundary northwards and put the Second Army in charge of the main offensive effort on the Gheluvelt Plateau. Plumer issued a preliminary order on 1 September, which defined the Second Army area of operations as Broodseinde and the area to the south. The plan was based on the use of much more medium and heavy artillery, which had been brought to the Gheluvelt Plateau from VIII Corps on the right flank of the Second Army and by removing more guns from the Third Army and Fourth Army, which were further south in Artois and Picardy. The heavy artillery reinforcements for the Second Army were to be used to destroy German concrete shelters and machine-gun nests, which were more numerous in the German battle zones than the outpost zones which had been captured since July and to engage in more counter-battery fire.[5] Few German concrete pill-boxes and machine gun nests had been destroyed during earlier preparatory bombardments and attempts at precision bombardment before attacks had also failed. The 112 heavy and 210 field guns and howitzers in the Second Army on 31 July were increased to 575 heavy and medium and 720 field guns and howitzers for the battle, which was equivalent to one artillery piece for every 5 ft (1.5 m) of the attack front, more than double the density at Pilckem Ridge.[6]

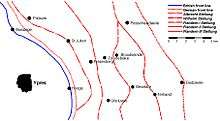

Plumer made tactical refinements to defeat the German defence-in-depth, by setting closer objectives and then fighting the principal battle against the German Eingreifdivisionen. Plumer ensured that the depth of the attacking divisions roughly corresponded to the depth of local German counter-attack reserves and the Eingreifdivisionen. By further reorganising the infantry reserves, more men were provided for the later stages of the advance, to defeat German counter-attacks. Advances of no more than 1,500 yd (1,400 m) were to be mand and then the infantry were to consolidate their positions, preferably on reverse-slopes.[7] When the Germans counter-attacked, they would encounter a British defence-in-depth protected by artillery and suffer many casualties to little effect, rather than the small and disorganised groups of infantry that the Germans had driven back on 31 July, 10 and 16 August.[8] After the big defeat at the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge on 20 September, the 4th Army changed the organisation of regiments and battalions in their defensive positions. During August, each German front-line division had kept two regiments in the front position with all six of their battalions; the third regiment was held further back in reserve. The front battalions had needed to be relieved much more frequently than expected, due to constant British bombardments and the wet weather. Periods in the line were exhausting and battalions had been sent where needed, dispersing units and disorganising their command structures. Regiments in reserve had not been able to conduct an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoß), which had left the battalions furthest forward unsupported, until Eingreifdivisionen arrived from the rearmost parts of the defences, some hours later.[9]

By 26 September, all three regiments of the German line-holding divisions (Stellungsdivisionen) had been deployed the front line, each holding an area 1,000 yd (910 m) wide and 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) deep, with one battalion in the front line, one in support and the third in close reserve. The three battalions of each regiment were to move forward, successively to engage British battalions, which leap-frogged through those of the previous stage of an attack. The Eingreifdivisionen were to deliver a methodical counter-attack with artillery and air support (Gegenangriff) later in the day, before the British could consolidate captured ground.[10] The change was intended to remedy the neutralisation of the front division reserves which had occurred on 20 September, because of the massed bombardments and barrages of the British artillery. The reserve battalion in each regimental sector would be able to counter-attack before the Eingreifdivisionen arrived. On 22 September, new tactical requirements were laid down, that more artillery bombardments were to be fired between British attacks, half of the artillery was to conduct counter-battery fire against British artillery and the other half to bombard infantry positions. More infantry raids were to be conducted to induce the British to reinforce the front line and make a denser target for the German artillery. Improvements in artillery observation in the battle zone were also ordered, to increase the accuracy of German artillery-fire as the British attacked.[11]

Prelude

German offensive preparations

On 23 September, Crown Prince Rupprecht wrote in his diary that the higher ground at Zonnebeke and Gheluvelt was vulnerable to another British attack and that it was vital that the Gegenstoß instant counter-attack tactic did not fail again. Next day, Rupprecht wrote that he hoped that another British attack would be delayed, as the 4th Army had insufficient reserves for the whole of the active front east of Ypres.[12] Rupprecht ordered a Gegenangriff (methodical counter-attack) against the British flank between the Menin Road and Polygon Wood, which had been lengthened by the British the advance on 20 September. Group Wytschaete (Gruppe Wijtschate was to attack with the 50th Reserve Division, which had relieved the Bavarian Ersatz Division. The attackers were to recapture 1,800 yd (1,600 m) of the Wilhelmstellung from the Menin road to Polygon Wood and then establish a position 100–150 yd (91–137 m) further on.[13] The commander of Reserve Infantry Regiment 229 (RIR 229) warned that the attack would fail unless it was most carefully prepared and supported by an attack by Group Ypres (Gruppe Ypern) opposite Polygon Wood but he was over-ruled. The counter-attack was postponed by one day and command was transferred to Major Litzmann, the commander of Reserve Infantry Regiment 230 (RIR 230).[14]

German plan

On 25 September, German troops were to conduct a Gegenangriff on the Fifth Army front opposite the 20th (Light) Division in XIV Corps and a bigger attack against the X Corps front, in the centre of the Second Army, south of the I Anzac Corps in Polygon Wood.[15] The 50th Reserve Division had been the Eingreif division for Group Dixmude (Gruppe Dixmude) from 10 August to 19 September and was moved south to the Menin area in reserve. The division relieved the Bavarian Ersatz Division on 21 September, Reserve Infantry Regiment 231 (RIR 231) south of the Menin road, RIR 230 north of the road to the Reutelbeek stream and RIR 229 north of the stream. Each regiment was to attack on a battalion front in each regimental sector, a width of about 1,800 yd (1,600 m) from the Menin road, north to Polygon Wood on the Gheluvelt Plateau. The attack was to begin at 5:15 a.m. and recapture the Wilhelmstellung opposite Gruppe Wytschaete, with an advance of about 500 yd (460 m) to the west, from the Menin road northwards to the Reutel, road south of Polygon Wood. A company of the 4th Army stormtroop battalion (Stoßtbataillon was to hold the Wilhelmstellung after it was captured.[16] The III Battalion, RIR 229 was to attack north of the Reutelbeek and the III Battalion, RIR 230 (Colonel Litzmann), was to attack from the Reutelbeek north to Polygon Wood; the Stoßtrupp was to attack in the area of RIR 231, on the Menin road.[14] The German artillery was augmented by 27 field artillery and 17 field howitzer batteries, the guns of the 25th and 207th divisions to the south, the 3rd Reserve Division and the long-range artillery group (Fernkampfgruppe) of Gruppe Ypern. The heavy artillery of Gruppe Tenbrielen to the south comprised 15 batteries of heavy howitzers and 5 batteries of heavy guns.[17]

British offensive preparations

On 21 September, Haig instructed the Fifth and Second armies to make the next step across the Gheluvelt Plateau, on a front of 8,500 yd (4.8 mi; 7.8 km). The I Anzac Corps was to conduct the main advance of about 1,200 yd (1,100 m), to complete the occupation of Polygon Wood and take the south end of Zonnebeke village.[18] The huge volume of shell-fire from both sides had cut up the ground and destroyed the roads. After the advance of 20 September, new road and light railway circuit extensions, to carry artillery and ammunition forward, were completed in four days of fine weather. Heavier equipment bogged in churned mud and had to be brought forward by wagons along the new roads and tracks, rather than being moved cross-country and many of the new routes could be seen by German artillery observers on Passchendaele ridge. British bombardment and counter-battery fire began immediately, with practice barrages fired daily as a minimum.[18] Artillery from VIII Corps and IX Corps, on the southern flank, fired bombardments to simulate preparations for an attack on Zandvoorde and Warneton. [19]

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.0 | 66 | dull |

| 21 | 0.0 | 62 | dull |

| 22 | 0.0 | 63 | clear |

| 23 | 0.0 | 65 | clear |

| 24 | 0.0 | 74 | dull |

| 25 | 0.0 | 75 | mist |

| 26 | 0.5 | 68 | mist |

| 27 | 0.0 | 67 | dull |

The Second Army altered its corps frontages soon after the attack of 20 September to concentrate each attacking division on a 1,000 yd (910 m) front. The frontages of VIII and IX corps were moved northwards, for X Corps to take over 600 yd (550 m) of front up to the southern edge of Polygon Wood, which kept the frontages of the two Australian divisions of I Anzac Corps to 1,000 yd (910 m) each. The 33rd Division (Major-General Reginald Pinney) replaced the 23rd Division (Major-General James Babington) beyond the Menin Road on the night of 24/25 September and the 5th Australian Division (Major-General Talbot Hobbs) and 4th Australian Division (Major-General Ewen Sinclair-Maclagan), replaced the 1st Australian Division and the 2nd Australian Division in Polygon Wood.[21]

The 33rd Division was to act in support of the 5th Australian Division in the forthcoming attack, taking over a length of the Wilhelmstellung captured by the Australians on 20 September. The divisional boundary ran along the Black Watch Corner–Reutel road, along the southern fringe of Polygon Wood. The left (northern) flank of the 33rd Division was in an area east of Carlisle Farm, with supporting units in the farm ruins and a reserve position 250 yd (230 m) back at Lone House. On 24 September, the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment took over the line for about 570 yd (520 m) from Black Watch Corner southwards, taking post in shell holes and scraps of trench, with two companies holding outposts and two in the support line. The relief had been most difficult, with guides getting lost and the approach march being made worse by German artillery-fire, which increased during the evening. The last troops took until 4:30 a.m. on 25 September to arrive and received a message that two Second Army practice barrages were due in the morning.[17]

Battle

25 September

50th Reserve Division

The attacking battalions of the 50th Reserve Division assembled during the night of 24 September with few casualties, covered by parties of the line-holding battalions which had moved into no-man's-land. The exceptionally large amount of supporting field and heavy artillery began a bombardment at 5:15 a.m. and the German infantry immediately fired red flares, signalling that the bombardment was falling short onto them, especially the III Battalion, RIR 230, south of the Reutelbeek. The troops retired until the bombardment began to creep forward at 5:30 a.m. and then advanced close behind it. German artillery-observation aircraft flew at low altitude and fired white flares showing the position of the German infantry to the artillery. On the right flank, the 4th Company of I Battalion, RIR 229, advanced against the 58th Australian Battalion, to form a defensive flank linking with the southern flank of RIR 49 of the 3rd Reserve Division in Gruppe Ypern to the north. Major Hethey, the Kampf-Truppen-Kommandeur (KTK, front battalion commander) of the area north of the Reutelbeek, had kept the 9th Company of the III Battalion, RIR 229 further back behind the northern flank as a tactical reserve.[22]

German contact-patrol aircrew established the position of the German line and reported this within ten minutes to the Gruppe Wijtschate headquarters. Hethey came forward and made Jerk House, a re-captured pillbox, the headquarters of the KTK, then ordered the 9th Company to reinforce the centre. At 10:00 a.m., the attack resumed but two companies of II Battalion, RIR 229 were not needed, as by 11:00 a.m., the objective had been reached. South of the Reutelbeek, the III Battalion, RIR 230 had advanced into muddy ground against the area held by the 4th King's and no ground was gained. The Stoßbataillon got forward, along the Menin road then was repulsed by a local counter-attack. British prisoners said that a British attack was due the next day.[23] On the right flank, Hethey organised the consolidation of the new positions during the night as the infantry companies had become mingled and all the commanders of the III Battalion and two in the I Battalion, had been wounded. The I Battalion (Captain Fischer) with the 4th, 3rd, 5th and 6th companies and attached Stoßtruppen, took over on the right near Polygon Wood. Hethey, with the III Battalion, a company of the II Battalion, RIR 229 and half of II Battalion, RIR 230, held the left flank in the Reutelbeek valley; the 1st, 7th and 8th companies of RIR 229 were kept back in Cameron Covert as a reserve. The III Battalion, Fusilier Regiment 90, the most advanced battalion of the fresh 17th Division, acted as an Eingreif unit in Flandern I Stellung.[24]

33rd Division

At 5:15 a.m. on 25 September, just as the 33rd Division completed the relief of the 23rd Division, a huge German bombardment began on the divisional front. The shell-fire reached so far back that road transport was made impossible and the sound of the bombardment and vibrations in the ground were felt at Boulogne.[25] SOS rockets were fired all along the 33rd Division front and British artillery and machine-guns replied at once. German infantry attacked up the Menin road from Gheluvelt, supported by flame-thrower teams, who fired burning oil 100 yd (91 m) forwards and upwards into trees, which had dried out in the sunny weather and caught fire immediately. The forward positions of the 1st Queen's (Royal West Surrey) (1st Queen's), on the right flank of the 100th Brigade were overrun and the 2nd Worcester in reserve at Inverness Copse lost half its strength in the bombardment. The 1/9th Highland Light Infantry (1/9th HLI) advanced quickly and filled a gap on the flank of the 1st Queen's and the remnants of the 2nd Worcester dug in as the 4th Battalion King's Liverpool (4th King's) of the 98th Brigade extended its right flank. The 4th King's regained touch with the 2nd Worcester after it had sidestepped southwards, to keep in contact with the 1st HLI behind the 1st Queen's and to add to the small-arms fire being directed at the attackers.[25]

On the left of the 98th Brigade, the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (2nd Argyll) and the 1st Middlesex were forced back and a company of each battalion was cut off by German troops by-passing their flanks. The 207th (Independent) Machine-gun Company had been placed behind the front line, with 16 Vickers machine-guns in groups, which watched as German officers led their troops forward over slight rise. When the second line of German infantry was visible on the forward slope as far down as their knees and too far forward to retreat, the guns opened fire. German aircrews flying low over the battlefield soon saw the British machine-guns. The aircrews called for artillery-fire and began to strafe the Vickers gun crews, causing many casualties, until the guns were withdrawn a short distance. During the day, the intensity of British artillery-fire diminished, due to the huge amount of German counter-battery fire cutting off the guns from their ammunition supply. Communication with the front line was cut, except for a few lucky message-runners who managed the three-hour journey from Brigade headquarters at the Tor Tops pillbox. The smoke and dust raised by the German and British bombardments obscured the battlefield and the troops who moved forward as reinforcements disappeared from view, many never to return.[26]

5th Australian Division

On 25 September, dawn broke fine but hazy, as preparations for the big attack due next day continued behind the Second Army front line. Practice barrages had been scheduled for 6:30 a.m. by all the artillery of the Second Army for an hour and then an 18-minute bombardment was due at 8:30 a.m. from the I Anzac Corps artillery. German artillery opened fire at 4:30 a.m. and an hour later, SOS rockets were fired in the 33rd Division sector on the left flank of X Corps and by the 5th Australian Division on the right flank of the I Anzac Corps. The quantity of German shell-fire was much greater than normal and at 7:15 a.m., a messenger pigeon returned to the 33rd Division headquarters, with news that the front line in the southern sector on the Menin road had been captured.[27][lower-alpha 2] German infantry had pushed back the 1st Middlesex and got machine-guns onto the Reutelbeek road on the boundary between X Corps and the I Anzac Corps at the Reutelbeek and Polygon Wood. Further south, an attack against the 4th King's of the 100th Brigade had been repulsed.[27]

German aircraft bombed the area behind the 5th Australian Division and hit the advanced divisional ammunition dump, which blew up, scattering bullets and hand grenades and destroying several lorries on the Menin road. The 58th Battalion of the 15th Australian Brigade on the right flank, requested reinforcements but the only troops available were those preparing for the attack on 26 September; a company of the 60th Battalion was sent up.[29] On the right flank, the 33rd Division sector was also under such bombardment that communication had become impossible. The commander of the 98th Brigade also called on troops, intended for the attack next day, to co-operate with the 15th Australian Brigade to the north. At 9:40 a.m., two companies the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders were sent forward to join the 1st Middlesex counter-attack.[30]

At the beginning of the German attack, the 58th Australian Battalion, in the south-western edge of Polygon Wood, saw the German infantry 500 yd (460 m) away, advancing in small "worm" columns.[14] The I Anzac Corps barrage came down within 15 seconds of the SOS call but it fell between the foremost German troops and the supporting units. The Australian infantry engaged the Germans with small-arms fire as they advanced from Cameron House and sheltered behind the remnants of hedges along the Reutel road. The 1st Middlesex on the right flank retreated and at 5:55 a.m., the attackers tried to rush the Australian right flank. The Germans were repulsed three times, although a German party held on in a shell-crater, from which they threw grenades into the right-flank post, until silenced by a rifle-grenade. Most of the surviving German infantry went under cover about 100 yd (91 m) from the Australians. At 6:10 a.m., a soldier of the 1st Middlesex reported to the Australians that the Germans had got into the 1st Middlesex front line close on the right, by when the Germans had placed a line of machine-guns along the Reutel road. The Australians swung their right flank further to the right, parallel to the road. Germans were then seen infiltrating towards the 1st Middlesex support line and more reinforcements were requested.[31]

The German barrage was at its greatest intensity but from 9:00 a.m., more troops went forward through the curtain of shells and extended the Australian right flank. The British practice barrages had fallen behind the German infantry, after which the accuracy of the British artillery reply increased. At 10:00 a.m., German troops were seen working forward from Jerk House towards several pillboxes in the 1st Middlesex area, on a rise 150 yd (140 m) behind the right flank of the 58th Australian Battalion. The Australian Stokes mortar crews ran short of bombs and the battalion was engaged from behind its right flank. From the German rear, a large number of troops advanced in close order and were engaged with small-arms fire.[32]

The 58th Battalion received warning of the 1st Middlesex counter-attack due at 2:00 p.m., with which the 60th Battalion was to co-operate. The 58th Battalion was ordered to hold on and at 12:30 p.m., a company of the 60th Battalion arrived and took post on the right flank. Two platoons of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders also arrived and extended the flank back past Black Watch Corner. No barrage was seen and no infantry attack took place at zero hour but at 2:03 p.m., the Australians attacked anyway, advancing from shell-hole to shell hole, covered by Stokes mortar fire and forced back the Germans. The advance was stopped while touch was sought with the 1st Middlesex and a small party of troops was found over to the right. Australian troops far out to the right rear saw two companies of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders advance down the head of the valley, with no protective barrage.[33]

The Scots advanced in two lines, through a huge amount of return-fire and the first line passed Lone House, south-west of Black Watch Corner, cutting off a small party of Germans. Together with a few men of the 1st Middlesex, the Argylls dug in with a second line 100 yd (91 m) behind, about 350 yd (320 m) behind the Australian flank; information about the new positions did not get back to the British and Australian commanders. The main German attack had ended at 11:00 a.m. but German airmen, unopposed by British aircraft, saw the advance of the Australian flank and ground observers watched reserves moving forward through Glencorse Wood under constant bombardment, which caused many British and Australian casualties. The Australian defensive flank was also bombarded and a retirement from there was contemplated, because of the number of German troops visible at Cameron House. After waiting until 5:00 p.m., in case of a British counter-attack, the Australians retired by dribbling back.[34]

The 98th Brigade planned to counter-attack behind a creeping barrage at 2:03 p.m., after a short bombardment and the 15th Australian Brigade was ordered to participate. At 4:55 p.m., Hobbs was told by the 33rd Divisional artillery, that the counter-attack had not taken place and by the 33rd divisional headquarters that the 98th Brigade had been seen advancing at 2:45 p.m. At 5:08 p.m., the 33rd Division reported that the counter-attack had succeeded but information from the 58th Battalion, was that many Germans had been seen assembling at Cameron House, opposite the corps boundary. At 7:30 p.m., the 98th Brigade reported that it had been forced back to the area of Verbeek Farm, about 750 yd (690 m) behind the right flank of the 58th Brigade.[35]

By nightfall, three of the four Australian battalions due for the attack on 26 September, had been committed. The 15th Australian Brigade in the north and the 4th King's of the 98th Brigade south of the gap made by the German counter-attack, had maintained their front line. On the Australian right, the Germans were level with the Australian support line, well behind the alignment on which the attacking troops must assemble. The Germans not been repulsed and the 33rd Division was uncertain where its troops were. Tapes to mark the start-lines for the next day's attack were almost due to be laid but officers of the 58th Battalion, who were to guide the assembling battalions, had been killed or wounded. The divisional dump and two forward dumps, from which the attacking troops were to have drawn their stores and ammunition, had been blown up and it had to be assumed that the Germans now knew of the attack due on 26 September. During the evening, Hobbs warned the 8th Australian Brigade (Brigadier-General Tivey) in reserve, that it might have to carry out the attack or detach two battalions for it.[36]

26 September

The 4th Suffolk and 5th Scottish Rifles replaced the Argylls and 1st Middlesex for the attack on 26 September, with orders to pass through them during the advance. With no knowledge of their positions, a creeping barrage could not be used and tanks were substituted, to advance in front of the infantry. Groups of the isolated battalions were discovered around Lone Farm 400 yd (370 m) south of Black Watch Corner.[37] RIR 230 managed to counter-attack the British near Jut Farm at about 2:00 p.m. and IR 78 of the 19th Reserve Division moved up behind IR 231. The main counter-attack was conducted by the 17th Division, which had been hurried forward from Gheluve to Gheluvelt and was attached to IR 231, to advance through the positions of the 50th Reserve Division, with the 236th Division on its right and capture the Wilhelmstellung.[38] The I Battalion, IR 75 and II Battalion, IR 75, attacked from the Menin road north to the Reutelbeek against the positions of the 100th Brigade, the first battalion in extended order and the other following in close formation. British artillery-observers directed so much artillery-fire onto the German infantry, that only a few parties reached the front line west of Polderhoek, where they were engaged by small-arms fire and the few Germans who kept going were dispersed by bayonet charges.[39]

As the 5th Australian Division attacked at 5:50 a.m.,, Hethey ordered a counter-attack from Jerk House by two companies of the II Battalion, RIR 230. The counter-attack took thirty prisoners but Hethey was killed at 6:30 a.m. and Lieutenant Glaubitz, then Lieutenant Weigel took over, being killed in turn around 7:00 a.m. Lieutenant Stolting of the machine-gun company was killed at 7:30 a.m., after which the adjutant, Lieutenant Körber, took over the defence and was the last man to get out of Polygon Wood.[40] The Germans retired from Jerk House at noon but machine-gun crews farther south gained a good view of the attack at about 11:00 a.m., when mist on the right flank dispersed. Troops of RIR 230 on the Polderhoek spur, saw the British advancing behind a creeping barrage, pushing to the south-east.[41]

At 1,100–2,000 yards (1,000–1,800 m), every machine-gun opened fire, the British artillery being unable fully to suppress them; seven machine-guns of the 1st Company fired more than 20,000 rounds.[42] Grenadier Regiment 89 was to attack through the positions held by RIR 229 on the right of the 50th Reserve Division but ran into artillery-fire in the Hollow Wood (Holle Bosch). The regiment was shattered by the Australian defensive barrage as it advanced over Reutel Hill, towards the south end of Polygon Wood. At 6:50 p.m., the Germans made a final counter-attack from Tower Hamlets spur to the south-west to Polygon Wood to the north-east. A few Germans got through the defensive barrages and were engaged by small-arms fire, suffering exceptional losses; around 8:30 p.m. the German counter-attacks stopped and a lull lasted for the rest of the night.[43]

Aftermath

Analysis

An intelligence summary of the Second Army assessed the German artillery in support of the Gegenagriff of 25 September, to have been the greatest concentration of artillery on a German divisional sector ever known and was nearly four times the usual quantity for a division. The attacking battalions had assembled during the night of 24/25 September, covered by parties of the line-holding battalions opposite the 33rd Division. The great mass of German artillery began a bombardment at 5:15 a.m. but fell short and German infantry fired red flares to signal to the German artillery that they were falling short, especially on the III Battalion, RIR 230, south of the Reutelbeek. The attacking troops withdrew slightly until 5:30 a.m., when the barrage began to creep forward. Rupprecht was well pleased with the results of the attack on 25 September and went on leave that evening, under the impression that the British would not be able to attack for a few days.[44]

In 1948, James Edmonds, the British official historian, wrote that the "desperate" German counter-attack had failed even to change the British zero hour for the attack on 26 September. Edmonds quoted Der Weltkrieg, the German official history, that on 26 September, counter-attacks by the specialist 17th, 236th and 4th Bavarian Eingreif divisions took 1 1⁄2–2 hours to move 0.62 miles (1 km), that their formations had been broken and their capacity to attack eliminated.[45] The German government presented allegations in November, that the 1st Middlesex had been ordered to shoot any armed German stretcher-bearers taken prisoner. It was alleged that this was against Article Six of the Geneva Convention of 1906, which allowed medical personnel to be armed for self-defence and defence of the wounded in their care; the claim was denied by the British government in its reply.[46]

Robert Perry wrote in 2014, that the German Gegenangriff had been successful in disrupting the British preparations to attack on 25 September. Most of the 98th Brigade was in front of Verbeek Farm, 700 yd (640 m) west of the original front line and it could be assumed that prisoners taken on 24 September had disclosed the date and time of the attack; Morland doubted that the attack should go ahead but was over-ruled by Plumer. The objectives of the 33rd Division were changed to the 98th Brigade covering the flank of the 5th Australian Division and the 100th Brigade recapturing the ground lost the day before. The 1st Anzac Corps also made sure that its divisions knew that there was no question of postponing the attack despite the vulnerability of the southern flank.[47]

Casualties

The 33rd Division lost 2,905 casualties and the 5th Australian Division had 3,723 losses from 25–26 September, the 15th Australian Brigade total being 1,203 men.[48] Detailed information on German casualties from 25–26 September is limited but the effect of the British attack on 26 September inflicted such casualties on the ground-holding and Eingreif divisions in its path, that all were relieved urgently.[49]

Subsequent operations

On 27 September, the 39th Division on the right flank of the X Corps defeated three German counter-attacks with artillery fire. On the 33rd Division front, after a report that Cameron House had been captured, a battalion attacked past it and reached the blue line, the original objective for the attack on 25 September. The 98th Brigade to the north attacked towards the 5th Australian Division, against determined German resistance and linked with the Australians in Cameron Covert at 3:50 p.m. A lull followed until 4:30 a.m. on 30 September, when an attack was made by regiments of the fresh 8th Division, the 45th Reserve Division and the 4th Army Sturmbataillon, with flame-throwers and a smoke screen, from the Menin road to the Reutelbeek against the 23rd Division (which had returned from reserve to take over the 33rd Division front). Massed small-arms fire repulsed the attack against the 70th Brigade, despite SOS signals to the artillery being obscured by mist and a smaller attempt at 6:00 a.m. was also defeated.[50]

Notes

- Bidwell and Graham wrote that since Plumer had described the new German system after the Battle of Messines, this was already known and lay behind the reservations of Major-General John "Tavish" Davidson, the BEF Director of Military Operations, to the Fifth Army plan for the attack of 31 July.[4]

- Power buzzer leads were broken and pigeons were killed or made unconscious by concussion from bursting shells.[28]

Footnotes

- Michelin 1919, pp. 23–24; Doughty 2005, pp. 382–282.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 231.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 235–236.

- Bidwell & Graham 1984, pp. 127–128.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 238, 244.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 239.

- Malkasian 2002, p. 41.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 247.

- Rogers 2011, p. 168.

- Rogers 2011, pp. 168–170.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 295.

- Bean 1941, p. 803.

- Perry 2014, p. 303.

- Bean 1941, p. 804.

- Moorhouse 2003, pp. 174–175; Bean 1941, pp. 799–809.

- Sheldon 2007, p. 167; Edmonds 1991, p. 283; Perry 2014, p. 303.

- Perry 2014, pp. 303–304.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 280.

- Bean 1941, pp. 791–796.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 69–82.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 282–283.

- Bean 1941, pp. 804–805.

- Bean 1941, pp. 804–807.

- Bean 1941, p. 816.

- Seton Hutchinson 2005, p. 67.

- Seton Hutchinson 2005, p. 68.

- Bean 1941, pp. 799–800.

- Ellis 1920, p. 240.

- Bean 1941, pp. 800–801.

- Bean 1941, p. 801.

- Bean 1941, p. 805.

- Bean 1941, p. 806.

- Bean 1941, p. 807.

- Bean 1941, p. 808.

- Bean 1941, pp. 802–803.

- Bean 1941, p. 809.

- Dunne 1938, pp. 392, 394.

- Sheldon 2007, p. 169.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 291.

- Bean 1941, p. 816; Sheldon 2007, p. 169.

- Bean 1941, p. 821.

- Bean 1941, p. 821; Edmonds 1991, p. 287.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 291–292.

- Bean 1941, pp. 803–804.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 284.

- Seton Hutchinson 2005, pp. 74–75.

- Perry 2014, pp. 318, 308–309.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 293; Bean 1941, p. 831.

- Sheldon 2007, pp. 176, 183.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 301.

References

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941) [1933]. The A. I. F. in France 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. IV (11th ed.). Sydney: Halstead Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-1710-4. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Bidwell, S.; Graham, D. (2004) [1984]. Fire-Power: British Army Weapons and Theories of War 1904–1945. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-216-2.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Dunne, J. C. (1989) [1938]. The War The Infantry Knew: 1914–1919: A Chronicle of Service in France and Belgium (Cardinal ed.). London: P. S. King and Son. ISBN 978-0-7474-0372-2.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Ellis, A. D. (1920). The Story of the Fifth Australian Division, Being an Authoritative Account of the Division's Doings in Egypt, France and Belgium. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 12016875. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Malkasian, C. (2002). A History of Modern Wars of Attrition. Westport: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97379-7.

- McCarthy, C. (1995). The Third Ypres: Passchendaele, the Day-By-Day Account. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-217-5.

- Moorhouse, B. (2003). Forged By Fire: The Battle Tactics and Soldiers of a World War One Battalion, The 7th Somerset Light Infantry. Kent: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-191-3.

- Perry, R. A. (2014). To Play a Giant's Part: The Role of the British Army at Passchendaele. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-78331-146-0.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-90603-376-7.

- Seton Hutchinson, G. (2005) [1921]. The Thirty-Third Division in France and Flanders 1915–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Waterlow & Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-995-1.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. London: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-564-4.

- Verdun and the Battles for its Possession. Clermont Ferrand: Michelin and Cie. 1919. OCLC 654957066. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

Further reading

Books

- Harington, C. (2017) [1935]. Plumer of Messines (facsimile pbk. Gyan Books, India ed.). London: John Murray. OCLC 186736178.

- Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War (1914–1918). Document (United States. War Department) 905. Washington D.C.: United States Army, American Expeditionary Forces, Intelligence Section. 1920. OCLC 565067054. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Theses

- Freeman, J. (2011). A Planned Massacre?: British Intelligence Analysis and the German Army at the Battle of Broodseinde, 4 October 1917 (PhD). Birmingham: Birmingham University. OCLC 767827490. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (PhD). London: London University. OCLC 557496951. Retrieved 13 November 2016.