Lahore

Lahore (/ləˈhɔːr/; Punjabi: لہور; Urdu: لاہور, pronounced [lɑːˈɦɔːr]) is the capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab, and is the country's 2nd largest city after Karachi, as well as the 18th largest city proper in the world.[6] Lahore is one of Pakistan's wealthiest cities with an estimated GDP of $65.14 billion (PPP) as of 2017.[4] Lahore is the largest city and historic cultural centre of the wider Punjab region,[7][8][9][10] and is one of Pakistan's most socially liberal,[11] progressive,[12] and cosmopolitan cities.[13]

Lahore

| |

|---|---|

.jpg)    .jpg)   Clockwise from the top: Badshahi Mosque, Wazir Khan Mosque, Naulakha Pavilion, Lahore Museum, Shalimar Gardens, Minar-e-Pakistan, Lahore Fort. | |

Emblem | |

| Nickname(s): The Heart of Pakistan, Paris of the East, City of Gardens, City of Hazrat Ali Hujwiri | |

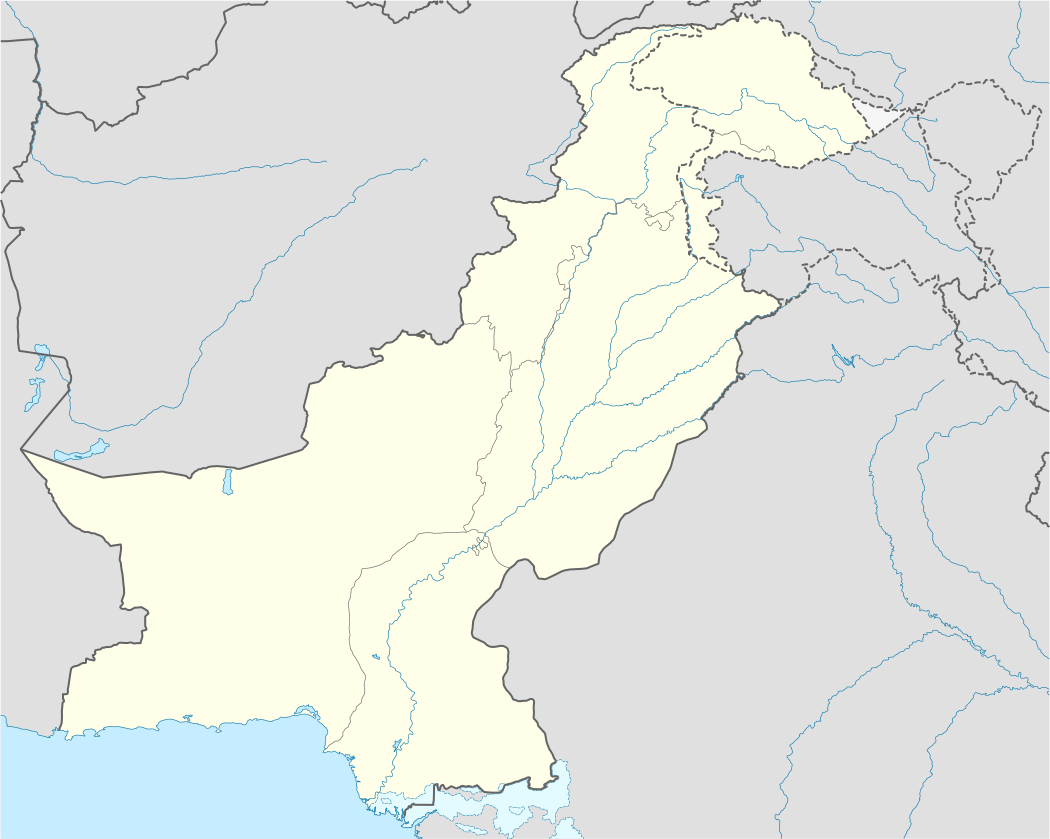

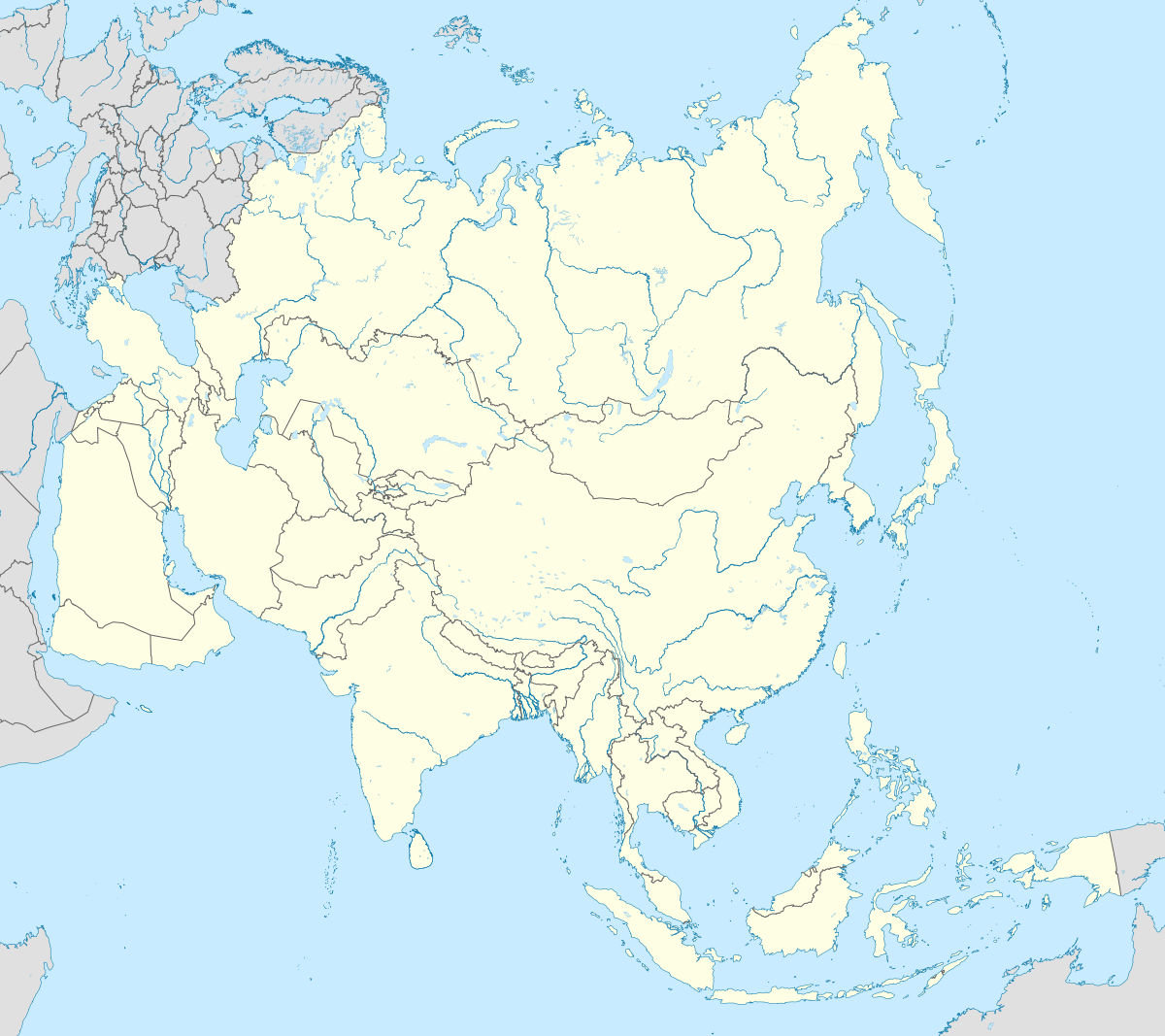

Lahore Location within Pakistan  Lahore Location within Asia  Lahore Lahore (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 31°32′59″N 74°20′37″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Division | Lahore |

| District | Lahore |

| Metropolitan corporation | 2013 |

| Zones | 10 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mubashar Javed |

| • Deputy Commissioner | Danish Afzal |

| • Deputy Mayors | 9 Zonal Mayors |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,772 km2 (684 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 217 m (712 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 11,126,285 |

| • Rank |

|

| • Density | 6,300/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Lahori |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PKT) |

| Postal code | 54000 |

| Dialing code | 042[3] |

| GDP/PPP | $65.14 billion (2017)[4] |

| HDI (2017) | |

| Website | www |

Lahore's origins reach into antiquity. The city has been controlled by numerous empires throughout the course of its history, including the Hindu Shahis, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, and Delhi Sultanate by the medieval era. Lahore reached the height of its splendour under the Mughal Empire between the late 16th and early 18th century, and served as its capital city for a number of years. The city was captured by the forces of the Afsharid ruler Nader Shah in 1739, and fell into a period of decay while being contested between the Afghans and the Sikhs. Lahore eventually became capital of the Sikh Empire in the early 19th century, and regained some of its lost grandeur.[14] Lahore was then annexed to the British Empire, and made capital of British Punjab.[15] Lahore was central to the independence movements of both India and Pakistan, with the city being the site of both the declaration of Indian Independence, and the resolution calling for the establishment of Pakistan. Lahore experienced some of the worst rioting during the Partition period preceding Pakistan's independence.[16] Following the success of the Pakistan Movement and subsequent independence in 1947, Lahore was declared capital of Pakistan's Punjab province.

Lahore exerts a strong cultural influence over Pakistan.[7] Lahore is a major center for Pakistan's publishing industry, and remains the foremost center of Pakistan's literary scene. The city is also a major centre of education in Pakistan,[17] with some of Pakistan's leading universities based in the city.[18] Lahore is also home to Pakistan's film industry, Lollywood, and is a major centre of Qawwali music.[19] The city also hosts much of Pakistan's tourist industry,[19][20] with major attractions including the Walled City, the famous Badshahi and Wazir Khan mosques and Sikh shrines. Lahore is also home to the Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens, both of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[20]

Etymology

The origins of Lahore's name are unclear. Lahore's name had been recorded by early Muslim historians as Lūhar, Lūhār, and Rahwar.[21] Al-Biruni referred to the city as Luhāwar in his 11th century work, Qanun,[21] while the poet Amir Khusrow, who lived during the Delhi Sultanate, recorded the city's name as Lāhanūr.[22] Yaqut al-Hamawi records the city's name as Lawhūr, mentioning that it's famously known as Lahāwar.[23] Rajput sources recorded the city's name as Lavkot.[22]

One theory suggests that Lahore's name is a corruption of the word Ravāwar, as R to L shifts are common in languages derived from Sanskrit.[24] Ravāwar is the simplified pronunciation of the name Iravatyāwar - a name possibly derived from the Ravi River, known as the Iravati River in the Vedas.[24][25] Another theory suggests the city's name may derive from the word Lohar, meaning "blacksmith."[26]

According to Hindu legend,[27][28] Lahore's name derives from Lavpur or Lavapuri ("City of Lava"),[29] and is said to have been founded by Prince Lava,[30] the son of Sita and Rama. The same account attributes the founding of nearby Kasur by his twin brother Prince Kusha.[31]

History

Early

No definitive records exist to elucidate Lahore's earliest history, and Lahore's ambiguous early history have given rise to various theories about its establishment and history. Hindu legend states that Keneksen, the founder of the Great Suryavansha dynasty, is believed to have migrated out from the city.[33] Early records of Lahore are scant, but Alexander the Great's historians make no mention of any city near Lahore's location during his invasion in 326 BCE, suggesting the city had not been founded by that point, or was unimportant.[34]

Ptolemy mentions in his Geographia a city called Labokla situated near the Chenab and Ravi Rivers which may have been in reference to ancient Lahore, or an abandoned predecessor of the city.[35] Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang gave a vivid description of a large and prosperous unnamed city when he visited the region in 630 CE that may have been Lahore.[36]

The first document that mentions Lahore by name is the Hudud al-'Alam ("The Regions of the World"), written in 982 CE[37] in which Lahore is mentioned as a town which had "impressive temples, large markets and huge orchards."[38][39]

Few other references to Lahore remain from before its capture by the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century. Lahore appears to have served as the capital of Punjab during this time under Anandapala of the Kabul Shahi empire, who had moved the capital there from Waihind.[40] The capital would later be moved to Sialkot following Ghaznavid incursions.[36]

Medieval

Ghaznavid

Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni captured Lahore on an uncertain date, but under Ghaznavid rule, Lahore emerged effectively as the empire's second capital.[36] In 1021, Sultan Mahmud appointed Malik Ayaz to the Throne of Lahore—a governorship of the Ghaznavid Empire. The city was captured by Nialtigin, the rebellious Governor of Multan, in 1034, although his forces were expelled by Malik Ayaz in 1036.[41]

With the support of Sultan Ibrahim Ghaznavi, Malik Ayaz rebuilt and repopulated the city which had been devastated after the Ghaznavid invasion. Ayaz erected city walls and a masonry fort built in 1037–1040 on the ruins of the previous one,[42] which had been demolished during the Ghaznavid invasion. A confederation of Hindu princes then unsuccessfully laid siege to Lahore in 1043-44 during Ayaz' rule.[36] The city became a cultural and academic centre, renowned for poetry under Malik Ayaz' reign.[43][44]

Lahore was formally made the eastern capital of the Ghaznavid empire in 1152,[14] under the reign of Khusrau Shah.[45] The city then became the sole capital of the Ghaznavid empire in 1163 after the fall of Ghazni.[46] The entire city of Lahore during the medieval Ghaznavid era was probably located west of the modern Shah Alami Bazaar, and north of the Bhatti Gate.[14]

Mamluk

In 1187, the Ghurids invaded Lahore,[36] ending Ghaznavid rule over Lahore. Lahore was made capital of the Mamluk Dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate following the assassination of Muhammad of Ghor in 1206. Under the reign of Mamluk sultan Qutbu l-Din Aibak, Lahore attracted poets and scholars from as far away as Turkestan, Greater Khorasan, Persia, and Mesopotamia. Lahore at this time had more poets writing in Persian than any city in Persia or Khorasan.[47][48]

Following the death of Aibak, Lahore came to be disputed among Ghurid officers. The city first came under control of the Governor of Multan, Nasir ad-Din Qabacha, before being briefly captured by the sultan of the Mamluks in Delhi, Iltutmish, in 1217.[36]

In an alliance with local Khokhars in 1223, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu of the Khwarazmian dynasty of modern-day Uzbekistan captured Lahore after fleeing Genghis Khan's invasion of Khwarazm.[36] Jalal ad-Din's then fled from Lahore to capture the city of Uch Sharif after Iltutmish's armies re-captured Lahore in 1228.[36]

The threat of Mongol invasions and political instability in Lahore caused future Sultans to regard Delhi as a safer capital for medieval Islamic India,[49] though Delhi had before been considered a forward base, while Lahore had been widely considered to be the centre of Islamic culture in the subcontinent.[49]

Lahore came under progressively weaker central rule under Iltutmish's descendants in Delhi - to the point that governors in the city acted with great autonomy.[36] Under the rule of Kabir Khan Ayaz, Lahore was virtually independent from the Delhi Sultanate.[36] Lahore was sacked and ruined by the Mongol army in 1241.[50] Lahore governor Malik Ikhtyaruddin Qaraqash fled the Mongols,[51] while the Mongols held the city for a few years under the rule of the Mongol chief Toghrul.[49]

In 1266, Sultan Balban reconquered Lahore, but in 1287 under the Mongol ruler Temür Khan,[49] the Mongols again overran northern Punjab. Because of Mongol invasions, Lahore region had become a city on a frontier, with the region's administrative centre shifted south to Dipalpur.[36] The Mongols again invaded northern Punjab in 1298, though their advance was eventually stopped by Ulugh Khan, brother of Sultan Alauddin Khalji of Delhi.[49] The Mongols again attacked Lahore in 1305.[52]

Tughluq

Lahore briefly flourished again under the reign of Ghazi Malik of the Tughluq dynasty between 1320 and 1325, though the city was again sacked in 1329, by Tarmashirin of the Central Asian Chagatai Khanate, and then again by the Mongol chief Hülechü.[36] Khokhars seized Lahore in 1342,[53] but the city was retaken by Ghazi Malik's son, Muhammad bin Tughluq.[36] The weakened city then fell into obscurity, and was captured once more by the Khokhars in 1394.[41] By the time Tamerlane captured the city in 1398 from Shayka Khokhar, he did not loot it because it was no longer wealthy.[33]

Late Sultanates

.jpg)

Timur gave control of the Lahore region to Khizr Khan, Governor of Multan, who later established the Sayyid dynasty in 1414 – the fourth dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate.[54] Lahore was briefly occupied by the Timurid Governor of Kabul in 1432-33.[49] Lahore began to be incurred upon yet again the Khokhar tribe, and so the city was granted to Bahlul Lodi in 1441 by the Sayyid dynasty in Delhi, though Lodi would then displace the Sayyids in 1451 by establishing himself upon the throne of Delhi.[36]

Bahlul Lodi installed his cousin, Tatar Khan, to be governor of the city, though Tatar Khan died in battle with Sikandar Lodi in 1485.[55] Governorship of Lahore was transferred by Sikandar Lodi to Umar Khan Sarwani, who quickly left management of this city to his son Said Khan Sarwani. Said Khan was removed from power in 1500 by Sikandar Lodi, and Lahore came under the governorship of Daulat Khan Lodi, son of Tatar Khan and former employer of Guru Nanak – founder of the Sikh faith.[55]

Mughals

Early Mughal

Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, captured Lahore in 1524 after being invited to invade by Daulat Khan Lodi, the Lodi governor of Lahore.[36] The city became refuge to Humayun and his cousin Kamran Mirza when Sher Shah Suri rose in power on the Gangetic Plains, displacing Mughal power. Sher Shah Suri continued to rise in power, and seized Lahore in 1540, though Humayun reconquered Lahore in February 1555.[36] The establishment of Mughal rule eventually led to the most prosperous era of Lahore's history.[36] Lahore's prosperity and central position has yielded more Mughal-era monuments in Lahore than either Delhi or Agra.[57]

By the time of rule of the Mughal empire's greatest emperors, a majority of Lahore's residents did not live within the walled city itself but instead lived in suburbs that had spread outside of the city's walls.[14] Only 9 of the 36 urban quarters around Lahore, known as guzars, were located within the city's walls during the Akbar period.[14] During this period, Lahore was closely tied to smaller market towns known as qasbahs, such as Kasur and Eminabad, as well as Amritsar, and Batala in modern-day India, which in turn, linked to supply chains in villages surrounding each qasbah.[14]

Akbar

Beginning in 1584, Lahore became the Mughal capital when Akbar began re-fortifying the city's ruined citadel, laying the foundations for the revival of the Lahore Fort.[14] Akbar made Lahore one of his original twelve subah provinces,[14] and in 1585–86 relegated governorship of the city and subah to Bhagwant Das, brother of Mariam-uz-Zamani, who was commonly known as Jodhabhai.[58]

Akbar also rebuilt the city's walls, and extended their perimeter east of the Shah Alami bazaar to encompass the sparsely populated Rarra Maidan.[14] The Akbari Mandi grain market was set up during this era, and continues to function until present-day.[14] Akbar also established the Dharampura neighbourhood in the early 1580s, which survives today.[59] The earliest of Lahore's many havelis date from the Akbari era.[14] Lahore's Mughal monuments were built under Akbar's reign of several emperors,[14] and Lahore reached its cultural zenith during this period, with dozens of mosques, tombs, shrines, and urban infrastructure developed during this period.

Jahangir

During the reign of Emperor Jahangir in the early 17th century, Lahore's bazaars were noted to be vibrant, frequented by foreigners, and stocked with a wide array of goods.[14] In 1606, Jehangir's rebel son Khusrau Mirza laid siege to Lahore after obtaining the blessings of the Sikh Guru Arjan Dev.[60] Jehangir quickly defeated his son at Bhairowal, and the roots of Mughal-Sikh animosity grew.[60] Sikh Guru Arjan Dev was executed in Lahore in 1606 for his involvement in the rebellion.[61] Emperor Jahangir chose to be buried in Lahore, and his tomb was built in Lahore's Shahdara Bagh suburb in 1637 by his wife Nur Jahan, whose tomb is also nearby.

Shah Jahan

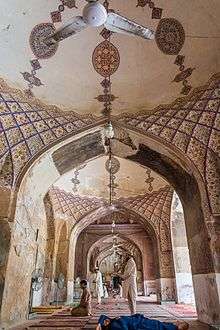

Jahangir's son, Shah Jahan reigned between 1628 and 1658 and was born in Lahore in 1592. He renovated large portions of the Lahore Fort with luxurious white marble and erected the iconic Naulakha Pavilion in 1633.[62] Shah Jahan lavished Lahore with some of its most celebrated and iconic monuments, such as the Shahi Hammam in 1635, and both the Shalimar Gardens and the extravagantly decorated Wazir Khan Mosque in 1641. The population of pre-modern Lahore probably reached its zenith during his reign, with suburban districts home to perhaps 6 times as many compared to within the Walled City.[14]

Aurangzeb

Shah Jahan's son, and last of the great Mughal Emperors, Aurangzeb, further contributed to the development of Lahore. Aurangzeb built the Alamgiri Bund embankment along the Ravi River in 1662 in order to prevent its shifting course from threatening the city's walls.[14] The area near the embankment grew into a fashionable locality, with several pleasure gardens laid near the bund by Lahore's gentry.[14] The largest of Lahore's Mughal monuments was raised during his reign, the Badshahi Mosque in 1673, as well as the iconic Alamgiri gate of the Lahore Fort in 1674.[63]

Late Mughal

Civil wars regarding succession to the Mughal throne following Aurangzeb's death in 1707 lead to weakening control over Lahore from Delhi, and a prolonged period of decline in Lahore.[64] Mughal preoccupation with the Marathas in the Deccan eventually resulted in Lahore being governed by a series of governors who pledged nominal allegiance to the ever weaker Mughal emperors in Delhi.[14]

Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah I died en route to Lahore as part of a campaign in 1711 to subdue Sikh rebels under the leadership of Banda Singh Bahadur.[36] His sons fought a battle outside Lahore in 1712 for succession to the Mughal crown, with Jahandar winning the throne.[36] Sikh rebels were defeated during the reign of Farrukhsiyar, when Abd as-Samad and Zakariyya Khan suppressed them.[36]

Nader Shah's brief invasion of the Mughal Empire in early 1739 wrested control away from Zakariya Khan Bahadur. Though Khan was able to win back control after the Persian armies had left,[36] Nader Shah's invasion shifted trade routes away from Lahore, and south towards Kandahar instead.[14] Indus ports near the Arabian Sea that served Lahore also silted up during this time, reducing the city's importance even further.[14]

Struggles between Zakariyya Khan's sons following his death in 1745 further weakened Muslim control over Lahore, thus leaving the city in a power vacuum, and vulnerable to foreign marauders.[65]

Durrani Empire

Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of the Afghan Durrani Empire, captured Lahore in January 1748,[36] Following Ahmed Shah Durrani's quick retreat, the Mughals entrusted Lahore to Mu’īn al-Mulk Mir Mannu.[36] Ahmad Shah Durrani again invaded in 1751, forcing Mir Mannu into signing a treaty that submitted Lahore to Afghan rule.[36] The Mughal Wazīr Ghazi Din Imad al-Mulk would seize Lahore in 1756, provoking Ahmad Shah Durrani to again invade in 1757, after which he placed the city under the rule of his son, Timur Shah Durrani.[36]

Durrani rule was briefly interrupted by the Maratha Empire's capture of Lahore in 1758 under Raghunathrao, who drove out the Afghans,[66] while a combined Sikh-Maratha defeated an Afghan assault in the 1759 Battle of Lahore.[67] Following the Third Battle of Panipat, Ahmad Shah Durrani crushed the Marathas and recaptured Lahore, Sikh forces quickly occupied the city after the Durranis withdrew from the city.[36] The Durranis invaded two more times, while the Sikhs would re-occupy the city after both invasions.[36]

Sikh

Early

Expanding Sikh Misls secured control over Lahore in 1767, when the Bhangi Misl state captured the city.[69] In 1780, The city was divided among three rulers, Gujjar Singh, Lahna Singh, and Sobha Singh. Instability resulting from this arrangement allowed nearby Amritsar to establish itself as the area's primary commercial centre in place of Lahore.[14]

Ahmad Shah Durrani's grandson, Zaman Shah invaded Lahore in 1796, and again in 1798-9.[36] Ranjit Singh negotiated with the Afghans for the post of ‘’subadar’’ to control Lahore following the second invasion.[36]

By the end of the 18th century, the city's population drastically declined, with its remaining resident's living within the city walls, while the extramural suburbs lay abandoned, forcing travelers to pass through abandoned and ruined suburbs for a few miles before reaching the city's gates.[14]

Sikh Empire

Following Zaman Shah’s 1799 invasion of Punjab, Ranjit Singh of nearby Gujranwala to consolidate his position in the aftermath of the invasion. Singh was able to seize control of the region after a series of battles with the Sikh Bhangi Misl chiefs who had seized Lahore in 1780.[36][71] His army marched to Anarkali, where according to legend, the gatekeeper of the Lohari Gate, Mukham Din Chaudhry, opened the gates allowing Ranjit Singh's army to enter Lahore.[64] After capturing the Lahore, Sikh soldiers immediately began plundering Muslim areas of the city until their actions were reined in by Ranjit Singh.[72]

Ranjit Singh's rule restored some of Lahore's lost grandeur, but at the expense of destroying the remaining Mughal architecture for its building materials.[14] He established a mint in the city in 1800,[64] and moved into the Mughal palace at the Lahore Fort after repurposing it for his own use in governing the Sikh Empire.[73] In 1801, he established the Gurdwara Janam Asthan Guru Ram Das to mark the site where Guru Ram Das was born in 1534.

Lahore became the empire's administrative capital, though nearby economic center of Amritsar had also been established as the empire's spiritual capital by 1802.[14] By 1812 Singh had mostly refurbished the city's defenses by adding a second circuit of outer walls surrounding Akbar's original walls, with the two separated by a moat. Singh also partially restored Shah Jahan's decaying Shalimar Gardens.[74] Ranjit Singh also built the Hazuri Bagh Baradari in 1818 to celebrate his capture of the Koh-i-Noor diamond from Shuja Shah Durrani in 1813.[70] He also erected the Gurdwara Dera Sahib to mark the site of Guru Arjan Dev's 1606 death. The Sikh royal court also endowed religious architecture in the city, including a number of Sikh gurdwaras, Hindu temples, and havelis.[75][76]

While much of Lahore's Mughal era fabric lay in ruins by the time of his arrival, Ranjit Singh's rule saw the re-establishment of Lahore's glory – though Mughal monuments suffered during the Sikh period. Singh's armies plundered most of Lahore's most precious Mughal monuments, and stripped the white marble from several monuments to send to different parts of the Sikh Empire during his reign.[77] Monuments plundered for decorative materials include the Tomb of Asif Khan, the Tomb of Nur Jahan, and the Shalimar Gardens.[78][64] Ranjit Singh's army also desecrated the Badshahi Mosque by converting it into an ammunition depot and a stable for horses.[79] The Sunehri Mosque in the Walled City of Lahore was also converted to a gurdwara,[80] while the Mosque of Mariyam Zamani Begum was repurposed into a gunpowder factory.[81]

Late

The Sikh royal court, or the Lahore Durbar, underwent a quick succession of rulers after the death of Ranjit Singh. His son Kharak Singh quickly died after taking the throne on 6 November 1840, while the next appointed successor Nau Nihal Singh to the throne died in an accident at Lahore's Hazuri Bagh also on 6 November 1840 - the very same day of Kharak Singh's death.[64] Maharaja Sher Singh was then selected as Maharajah, though his claim to the throne was quickly challenged by Chand Kaur, widow of Kharak Singh and mother of Nau Nihal Singh, who quickly seized the throne.[64] Sher Singh raised an army that attacked Chand Kaur's forces in Lahore on 14 January 1841. His soldiers mounted weaponry on the minarets of the Badshahi Mosque in order to target Chand Kaur's forces in the Lahore Fort, destroying the fort's historic Diwan-e-Aam.[79] Kaur quickly ceded the throne, but Sher Sing was then assassinated in 1843 in Lahore's Chah Miran neighborhood along with his Wazir Dhiyan Singh.[70] Dhyan Singh's son, Hira Singh, sought to avenge his father's death by laying siege to Lahore in order to capture his father's assassins. The siege resulted in the capture of his father's murderer, Ajit Singh.[64] Duleep Singh was then crowned Maharajah, with Hira Singh as his Wazir, but his power would be weakened by continued infighting among Sikh nobles,[64] as well as confrontations against the British during the two Anglo-Sikh Wars

After the conclusion of the two Anglo-Sikh wars, the Sikh empire fell into disarray, resulting in the fall of the Lahore Durbar, and commencement of British rule after they captured Lahore and the wider Punjab Region.[64]

British

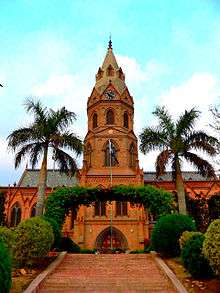

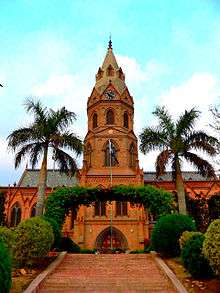

Government College University

Government College University

.jpg)

The British East India Company seized control of Lahore in February 1846 from the collapsing Sikh state, and occupied the rest of Punjab in 1848.[14] Following the defeat of the Sikhs at the Battle of Gujrat, British troops formally deposed Maharaja Duleep Singh in Lahore that same year.[14] Punjab was then annexed to the British Indian Empire in 1849.[14]

At the commencement of British rule, Lahore was estimated to have a population of 120,000.[82] Prior to annexation by the British, Lahore's environs consisted mostly of the Walled City surrounded by plains interrupted by settlements to the south and east, such as Mozang and Qila Gujar Singh, which have since been engulfed by modern Lahore. The plains between the settlements also contained the remains of Mughal gardens, tombs, and Sikh-era military structures.[83]

The British viewed Lahore's Walled City as a bed of potential social discontent and disease epidemics, and so largely left the inner city alone, while focusing development efforts in Lahore's suburban areas, and Punjab's fertile countryside.[84] The British instead laid out their capital city in an area south of the Walled City that would first come to be known as “Donald's Town” before being renamed "Civil Station."[85]

Under early British rule, formerly prominent Mughal-era monuments that were scattered throughout Civil Station were also re-purposed, and sometimes desecrated – including the Tomb of Anarkali, which the British had initially converted to clerical offices before re-purposing it as an Anglican church in 1851.[86] The 17th century Dai Anga Mosque was converted into railway administration offices during this time, the tomb of Nawab Bahadur Khan converted into a storehouse, and tomb of Mir Mannu was used as a wine shop.[87] The British also used older structures to house municipal offices, such as the Civil Secretariat, Public Works Department, and Accountant General's Office.[88]

The British built the Lahore Railway Station just outside the Walled City shortly after the Mutiny of 1857, and so built the station in the style of a medieval castle to ward off any potential future uprisings, with thick walls, turrets, and holes to direct gun and cannon fire for defence of the structure.[89] Lahore's most prominent government institutions and commercial enterprises came to be concentrated in Civil Station in a half-mile wide area flanking The Mall, where unlike in Lahore's military zone, the British and locals were allowed to mix.[90] The Mall continues to serve as the epicentre of Lahore's civil administration, as well as one of its most fashionable commercial areas. The British also laid the spacious Lahore Cantonment to the southeast of the Walled City at the former village of Mian Mir, where unlike around The Mall, laws did exist against the mixing of different races.

Lahore was visited on 9 February 1870 by Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh – a visit in which he received delegations from the Dogras of Jammu, Maharajas of Patiala, the Nawab of Bahawalpur, and other rulers from various Punjabi states.[91] During the visit, he visited several of Lahore's major sights.[91] British authorities built several important structures around the time of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887 in the distinct Indo-Saracenic style. The Lahore Museum and Mayo School of Industrial Arts were both established around this in this style.[92]

The British carried out a census of Lahore in 1901, and counted 20,691 houses in the Walled City.[93] An estimated 200,000 people lived in Lahore at this time.[82] Lahore's posh Model Town was established as a "garden town" suburb in 1921, while Krishan Nagar locality was laid in the 1930s near The Mall and Walled City.

Lahore played an important role in the independence movements of both India[94] and Pakistan. The Declaration of the Independence of India was moved by Jawaharlal Nehru and passed unanimously at midnight on 31 December 1929 at Lahore's Bradlaugh Hall.[95] The Indian Swaraj flag was adopted this time as well. Lahore's jail was used by the British to imprison independence activists such as Jatin Das, and was also where Bhagat Singh was hanged in 1931.[96] Under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah The All India Muslim League passed the Lahore Resolution in 1940, demanding the creation of Pakistan as a separate homeland for the Muslims of India.[97]

Partition

The 1941 census showed that city of Lahore had a population of 671,659, of which was 64.5% Muslim, with the remainder 35% being Hindu and Sikh, alongside a small Christian community.[16][98] The population figure was disputed by Hindus and Sikhs before the Boundary Commission that would draw the Radcliffe Line to demarcate the border of the two new states based on religious demography.[16] In a bid to have Lahore awarded to India, they argued that the city was only 54% Muslim, and that Hindu and Sikh domination of the city's economy and educational institutions should trump Muslim demography.[16] Two-thirds of shops, and 80% of Lahore's factories belonged to the Hindu and Sikh community.[16] Kuldip Nayyar reported that Cyril Radcliffe in 1971 had told him that he originally had planned to give Lahore to the new Dominion of India,[99][100][101] but decided to place it within the Dominion of Pakistan, which he saw as lacking a major city as he had already awarded Calcutta to India.[102][99][100]

As tensions grew over the city's uncertain fate, Lahore experienced Partition's worst riots.[16] Carnage ensued in which all three religious groups were both victims and perpetrators.[103] Early riots in March and April 1947 destroyed 6,000 of Lahore 82,000 homes.[16] Violence continued to rise throughout the summer, despite the presence of armoured British personnel.[16] Hindus and Sikhs began to leave the city en masse as their hopes that the Boundary Commission to award the city to India came to be regarded as increasingly unlikely. By late August 1947, 66% of Hindus and Sikhs had left the city.[16] The Shah Alami Bazaar, once a largely Hindu quarter of the Walled City, was entirely burnt down during subsequent rioting.[104]

When Pakistan's independence was declared on 14 August 1947, the Radcliffe Line had not yet been announced, and so cries of Long live Pakistan and God is greatest were heard intermittently with Long live Hindustan throughout the night.[16] On 17 August 1947, Lahore was awarded to Pakistan on the basis of its Muslim majority in the 1941 census, and was made capital of the Punjab province in the new state of Pakistan. The city's location near the Indian border meant that it received large numbers of refugees fleeing eastern Punjab and northern India, though it was able to accommodate them given the large stock of abandoned Hindu and Sikh properties that could be re-distributed to newly arrived refugees.[16]

Modern

Partition left Lahore with a much weakened economy, and a stymied social and cultural scene that had previously been invigorated by the city's Hindus and Sikhs.[16] Industrial production dropped to one third of pre-Partition levels by end of the 1940s, and only 27% of its manufacturing units were operating by 1950, and usually well-below capacity.[16] Capital flight further weakened the city's economy while Karachi industrialized and became more prosperous.[16] The city's weakened economy, and proximity to the Indian border, meant that the city was deemed unsuitable to be the Pakistani capital after independence. Karachi was therefore chosen to be capital on account of its relative tranquility during the Partition period, stronger economy, and better infrastructure.[16]

.jpg)

After independence, Lahore slowly regained its significance as an economic and cultural centre of western Punjab. Reconstruction began in 1949 of the Shah Alami Bazaar, the former commercial heart of the Walled City until it was destroyed in the 1947 riots.[104] The Tomb of Allama Iqbal was built in 1951 to honour the philosopher-poet who provided spiritual inspiration for the Pakistan movement.[16] In 1955, Lahore was selected to be capital of all West Pakistan during the single-unit period that lasted until 1970.[16] Shortly afterwards, Lahore's iconic Minar-e-Pakistan was completed in 1968 to mark the spot where the Pakistan Resolution was passed.[16] With support from the United Nations, the government was able to rebuild Lahore, and most scars from the communal violence of Partition were ameliorated.

The second Islamic Summit Conference was held in the city in 1974.[105] In retaliation for the destruction of the Babri Masjid in India by Hindu fanatics, riots erupted in 1992 in which several non-Muslim monuments were targeted, including the tomb of Maharaja Sher Singh,[70] and the former Jain temple near the Mall. In 1996, the International Cricket Council Cricket World Cup final match was held at the Gaddafi Stadium in Lahore.[106]

Eight people were killed in the March 2009 attack on the Sri Lanka national cricket team in Lahore. The Walled City of Lahore restoration project began in 2009, when the Punjab government restored the Royal Trail from Akbari Gate to the Lahore Fort with money from the World Bank.[107]

Geography

| Lahore | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lying between 31°15′—31°45′ N and 74°01′—74°39′ E, Lahore is bounded on the north and west by the Sheikhupura District, on the east by Wagah, and on the south by Kasur District. The Ravi River flows on the northern side of Lahore. Lahore city covers a total land area of 404 square kilometres (156 sq mi). Lahore is located approximately 24 kilometres (15 mi) from the border with India.

Climate

Lahore has a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh). The hottest month is June, when average highs routinely exceed 40 °C (104.0 °F). The monsoon season starts in late June, and the wettest month is July,[108] with heavy rainfalls and evening thunderstorms with the possibility of cloudbursts. The coolest month is January with dense fog.[109]

The city's record high temperature was 48.3 °C (118.9 °F), recorded on 30 May 1944.[110] 48 °C (118 °F) was recorded on 10 June 2007.[111][112] At the time the meteorological office recorded this official temperature in the shade, it reported a heat index in direct sunlight of 55 °C (131 °F). The record low is −1 °C (30 °F), recorded on 13 January 1967.[113] The highest rainfall in a 24-hour period is 221 millimetres (8.7 in), recorded on 13 August 2008.[114] On 26 February 2011, Lahore received heavy rain and hail measuring 4.5 mm (0.18 in), which carpeted roads and sidewalks with measurable hail for the first time in the city's recorded history.[115][116]

| Climate data for Lahore (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.8 (82.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

46.1 (115.0) |

48.3 (118.9) |

47.2 (117.0) |

46.1 (115.0) |

42.8 (109.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

48.3 (118.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

27.1 (80.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

38.6 (101.5) |

40.4 (104.7) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.9 (91.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

24.3 (75.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 23.0 (0.91) |

28.6 (1.13) |

41.2 (1.62) |

19.7 (0.78) |

22.4 (0.88) |

36.3 (1.43) |

202.1 (7.96) |

163.9 (6.45) |

61.1 (2.41) |

12.4 (0.49) |

4.2 (0.17) |

13.9 (0.55) |

628.8 (24.78) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 218.8 | 215.0 | 245.8 | 276.6 | 308.3 | 269.0 | 227.5 | 234.9 | 265.6 | 290.0 | 259.6 | 222.9 | 3,034 |

| Source 1: NOAA (1961-1990) [117] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: PMD[118] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1881 | 138,878 | — |

| 1891 | 159,947 | +15.2% |

| 1901 | 186,884 | +16.8% |

| 1911 | 228,687 | +22.4% |

| 1921 | 281,781 | +23.2% |

| 1931 | 400,075 | +42.0% |

| 1941 | 671,659 | +67.9% |

| 1951 | 1,130,000 | +68.2% |

| 1961 | 1,630,000 | +44.2% |

| 1972 | 2,198,890[119] | +34.9% |

| 1981 | 2,988,486[119] | +35.9% |

| 1998 | 5,209,088[119] | +74.3% |

| 2017 | 11,126,285[119] | +113.6% |

Population

The results of the 2017 Census determined the population to be at 11,126,285,[2] with an annual growth rate of 4.07% since 1998.[120] Gender-wise, 52.35% of the population is male, while 47.64% is female, and transgender people make only 0.01% of the population.[120] Lahore is a young city with over 40% of its inhabitants below the age of 15. The average life expectancy stand at less than 60 years of age.[121]

Religion

The city has a Muslim majority (97%), Christian (2%) minority population, Sikh and Hindu constitute (1%) combined.[122] There is also a small but longstanding Zoroastrian community. Additionally, Lahore contains some of Sikhism's holiest sites, and is a major Sikh pilgrimage site.[123][124]

According to the 1998 census, 94% of Lahore's population is Muslim, up from 60% in 1941. Other religions include Christians (5.80% of the total population, though they form around 9.0% of the rural population) and small numbers of Ahmediya, Bahá'ís, Hindus, Parsis and Sikhs. Lahore's first church was built during the reign of Emperor Akbar in the late 16th century, which was then leveled by Shah Jahan in 1632.[125]

Languages

The Punjabi language is the most-widely spoken native language in Lahore, with 87% of Lahore counting it as their first language according to the 1998 Census,[126][127] Lahore is the largest Punjabi-speaking city in the world.

Urdu and English are used as official languages and as mediums of instruction and media administration. However Punjabi is also taught at graduation level and used in theaters, films and newspapers from Lahore.[128][129] Several Lahore based prominent educational leaders, researchers, and social commentators demand that Punjabi language should be declared as the medium of instruction at the primary level and official use in Punjab assembly, Lahore.[130][131]

Cityscape

.jpg)

Urban form

Lahore's modern cityscape consists of the historic Walled City of Lahore in the northern part of the city, which contains several world and national heritage sites. Lahore's urban planning was not based on geometric design but was instead built piecemeal, with small cul-de-sacs, katrahs and galis developed in the context of neighbouring buildings.[14] Though certain neighbourhoods were named for particular religious or ethnic communities, the neighbourhoods themselves typically were diverse and were not dominated by the namesake group.[14]

By the end of the Sikh rule, most of Lahore's massive haveli compounds had been occupied by settlers. New neighbourhoods occasionally grew up entirely within the confines of an old Mughal haveli, such as the Mohallah Pathan Wali, which grew within the ruins of a haveli of the same name that was built by Mian Khan.[14] By 1831, all Mughal Havelis in the Walled City had been encroached upon by the surrounding neighbourhood,[14] leading to the modern-day absence of any Mughal Havelis in Lahore.

A total of thirteen gates once surrounded the historic walled city. Some of the remaining gates include the Raushnai Gate, Masti Gate, Yakki Gate, Kashmiri Gate, Khizri Gate, Shah Burj Gate, Akbari Gate and Lahori Gate. Southeast of the walled city is the spacious British-era Lahore Cantonment.

Architecture

Lahore is home to numerous monuments from the Mughal Dynasty, Sikh Empire, and British Raj. The architectural style of the Walled City of Lahore has traditionally been influenced by Mughal and Sikh styles.[132] The leafy suburbs to the south of the Old City, as well as the Cantonment southwest of the Old City, were largely developed under British colonial rule, and feature colonial-era buildings built alongside leafy avenues.

Sikh period

By the arrival of the Sikh Empire, Lahore had decayed from its former glory as the Mughal capital. Rebuilding efforts under Ranjit Singh and his successors were influenced by Mughal practices, and Lahore was known as the 'City of Gardens' during the Ranjit Singh period.[133][134] Later British maps of the area surrounding Lahore dating from the mid-19th century show many walled private gardens which were confiscated from the Muslim noble families bearing the names of prominent Sikh nobles – a pattern of patronage which was inherited from the Mughals.

While much of Lahore's Mughal era fabric lay in ruins by the time of his arrival, Ranjit Singh's army's plundered most of Lahore's most precious Mughal monuments, and stripped the white marble from several monuments to send to different parts of the Sikh Empire.[77] Monuments plundered of their marble include the Tomb of Asif Khan, Tomb of Nur Jahan, the Shalimar Gardens were plundered of much of its marble and costly agate.[78][64] The Sikh state also demolished a number of shrines and monuments laying outside the city's walls.[135]

Sikh rule left Lahore with several monuments, and a heavily altered Lahore Fort. Ranjit Singh's rule had restored Lahore to much of its last grandeur,[14] and the city was left with a large number of religious monuments from this period. Several havelis were built during this era, though only a few still remain.[14]

British period

As capital of British Punjab, British colonialists made a lasting architectural impression on the city. Structures were built predominantly in the Indo-Gothic style – a syncretic architectural style that blends elements of Victorian and Islamic architecture, or in the distinct Indo-Saracenic style. The British also built neoclassical Montgomery Hall, which today serves as the Quaid-e-Azam Library.[136]

Lawrence Gardens were also laid near Civil Station, and were paid for by donations solicited from both Lahore's European community, as well as from wealthy locals. The gardens featured over 600 species of plants, and were tended to by a horticulturist sent from London's Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.[137]

The British authorities built several important structures around the time of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887 in the distinct Indo-Saracenic style. The Lahore Museum and Mayo School of Industrial Arts were both established around this in this style.[92] Other prominent examples of the Indo-Saracenic style in Lahore include Lahore's prestigious Aitchison College, the Punjab Chief Court (today the Lahore High Court), Lahore Museum and University of the Punjab. Many of Lahore's most important buildings were designed by Sir Ganga Ram, who is sometimes called the "Father of modern Lahore."[138]

Parks and gardens

The Shalimar Gardens were laid out during the reign of Shah Jahan and were designed to mimic the Islamic paradise of the afterlife described in the Qur'an. The gardens follow the familiar charbagh layout of four squares, with three descending terraces.

The Lawrence Garden was established in 1862 and was originally named after Sir John Lawrence, late 19th-century British Viceroy to India. The Circular Garden, which surrounds on the Walled City on three sides, was established by 1892.[64]

The many other gardens and parks in the city include Hazuri Bagh, Iqbal Park, Mochi Bagh, Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park, Model Town Park, Race Course Park, Nasir Bagh Lahore, Jallo Park, Lahore Zoo Safari Park, and Changa Manga, a man-made forest near Lahore in the Kasur district. Another example is the Bagh-e-Jinnah, a 141-acre (57 ha) botanical garden that houses entertainment and sports facilities as well as a library.[139][140]

Economy

PIA Head Office

PIA Head Office

As of 2008, the city's gross domestic product (GDP) by purchasing power parity (PPP) was estimated at $40 billion with a projected average growth rate of 5.6 percent. This is at par with Pakistan's economic hub, Karachi, with Lahore (having half the population) fostering an economy that is 51% of the size of Karachi's ($78 billion in 2008).[141] The contribution of Lahore to the national economy is estimated to be 11.5% and 19% to the provincial economy of Punjab.[142] As a whole Punjab has $115 billion economy making it first and to date only Pakistani Subdivision of economy more than $100 billion at the rank 144.[141] Lahore's GDP is projected to be $102 billion by the year 2025, with a slightly higher growth rate of 5.6% per annum, as compared to Karachi's 5.5%.[141][143]

A major industrial agglomeration with about 9,000 industrial units, Lahore has shifted in recent decades from manufacturing to service industries.[144] Some 42% of its work force is employed in finance, banking, real estate, community, cultural, and social services.[144] The city is Pakistan's largest software & hardware producing centre,[144] and hosts a growing computer-assembly industry.[144] The city has always been a centre for publications where 80% of Pakistan's books are published, and it remains the foremost centre of literary, educational and cultural activity in Pakistan.[17]

The Lahore Expo Centre is one of the biggest projects in the history of the city and was inaugurated on 22 May 2010.[145] Defense Raya Golf Resort, also under construction, will be Pakistan's and Asia's largest golf course. The project is the result of a partnership between DHA Lahore and BRDB Malaysia. The rapid development of large projects such as these in the city is expected to boost the economy of the country.[146] Ferozepur Road of the Central business districts of Lahore contains high-rises and skyscrapers including Kayre International Hotel and Arfa Software Technology Park.

Transport

Public transportation

Lahore's main public transportation system is operated by the Lahore Transport Company (LTC) and Punjab Mass Transit Authority (PMTA). The backbone of its public transport network is the PMTA's Lahore Metrobus and soon to be Orange Line of the Lahore Metro train. LTC and PMTA also operates an extensive network of buses, providing bus service to many parts of the city and acting as a feeder system for the Metrobus.

Metro Bus

The Lahore Metrobus, is a bus rapid transit service operating in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan.[147] Lahore Metrobus service is integrated with Lahore Transport Company's local bus service to operate as one urban transport system, providing seamless transit service across Lahore District with connections to neighboring suburban communities.

Metro Train

Orange Line

The Orange Line Metro Train is an automated rapid transit system in Lahore.[148][149] The Orange line is the first of the three proposed rail lines proposed for the Lahore Metro. The line spans 27.1 km (16.8 mi) with 25.4 km (15.8 mi) elevated and 1.72 km (1.1 mi) underground and have a cost of 251.06 billion Rupees($1.6 billion).[150][151] The line consists of 26 subway stations and is designed to carry over 250,000 passengers daily. CRRC Zhuzhou Locomotive rolled out the first of 27 trains for the metro on 16 May 2017.[152] Successful initial test trials were run in mid 2018.[153] Since Lt Gen. (R) Asim Saleem Bajwa became the chairman of CPEC Authoriy,[154] he boosted the work already going under his supervision and has announced the Orange Line Train will open as soon as 23 March 2020.[155]

Blue Line

The Blue Line is a proposed 24 kilometres (15 mi) line from Chauburji to College Road, Township.

Purple Line

The Purple Line is a proposed 32 km Airport rail link.

Taxi and Rickshaw

Radio cab services Uber and Careem are available in the city. These taxis need to be booked in advance by apps or by calling their number. Motorcycle ride is also available in the city which have been introduced by private companies. These motorcycles need to be booked in advance by apps.

Auto rickshaws play an important role of public transport in Lahore. There are 246,458 auto rickshaws, often simply called autos, in the city. Motorcycle rickshaws, usually called "chand gari" (moon car) or "chingchi" (after the Chinese company Jinan Qingqi Motorcycle Co. Ltd who first introduced these to the market) are also a very common means of domestic travel. Since 2002, all auto rickshaws have been required to use CNG as fuel.[156]

Urban (LOV) Wagon / Mini Bus

Medium-sized vans/wagons or LOVs(Low Occupancy Vehicle) run on routes throughout the city. They function like buses, and operate on many routes throughout the city.[157][158]

Intercity transportation

Lahore Junction Station serves as the main railway station for Lahore, and serves as a major hub for all Pakistan Railway services in northern Pakistan. It includes services to Peshawar and national capital Islamabad-Rawalpindi, and long-distance services to Karachi and Quetta. Lahore Cantonment Station also operates a few trains.

The Lahore Badami Bagh Bus Terminal serves as a hub for intercity bus services in Lahore, served by multiple bus companies providing a comprehensive network of services in Punjab and neighboring provinces.

Airports

Pakistan's third busiest airport, Allama Iqbal International Airport (IATA: LHE), straddles the city's eastern boundary. The new passenger terminal was opened in 2003, replacing the old terminal which now serves as a VIP and Hajj lounge. The airport was named after the national poet-philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal.[159] and is a secondary hub for the national flag carrier, Pakistan International Airlines.[160] Walton Airport in Askari provides general aviation facilities. In addition, Sialkot International Airport (IATA: SKT) and Faisalabad International Airport (IATA: LYP) also serve as alternate airports for the Lahore area in addition to serving their respective cities.

Allama Iqbal International Airport connects Lahore with many cities worldwide (including domestic destinations) by both passenger and cargo flight including Ras al Khaimah, Guangzhou (begins 28 August 2018),[161] Ürümqi,[162] Abu Dhabi, Barcelona,[163] Beijing–Capital, Copenhagen, Dammam, Delhi, Dera Ghazi Khan, Doha, Dubai–International, Islamabad, Jeddah, Karachi, Kuala Lumpur–International, London–Heathrow, Manchester, Medina, Milan–Malpensa, Multan, Muscat, Oslo–Gardermoen, Paris–Charles de Gaulle, Peshawar, Quetta, Rahim Yar Khan, Riyadh, Salalah,[164] Tokyo–Narita, Toronto–Pearson, Mashhad, Bangkok–Suvarnabhumi, Tashkent[165]

Roads

There are a number of municipal, provincial and federal roads that serve Lahore.

- Municipal roads

- Canal Road (serves as the major north–south artery)

- Provincial highways

- Lahore Ring Road

- Lahore–Kasur Road (Ferozepur Road)

- Lahore–Raiwind Road (Raiwind Road)

- Lahore–Sharaqpur Road (Sagianwala Bypass Road)

- Lahore–Wagah Road

- Grand Trunk Road (G.T Road )

- Federal highways

- M-2 motorway

- M-3 motorway

- M-11 motorway

- N-5 National Highway (Multan Road)

- N-60 National Highway (Sargodha–Lahore road)

Government

Metropolitan Corporation

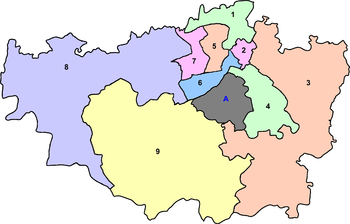

Under Punjab Local Government Act 2013, Lahore is a metropolitan area and under the authority of the Metropolitan Corporation Lahore.[166] The district is divided into 9 zones, each with its own elected Deputy Mayor. The Metropolitan Corporation Lahore is a body of those 9 deputy, as well as the city's mayor – all of whom are elected in popular elections. The Metropolitan Corporation approves zoning and land use, urban design and planning, environmental protection laws, as well as provide municipal services.

Mayor

As per the Punjab Local Government Act 2013, the Mayor of Lahore is the elected head of the Metropolitan Corporation of Lahore. The mayor is directly elected in municipal elections every four years alongside 9 deputy town mayors. Mubashir Javed of the Pakistan Muslim League (N) was elected mayor of Lahore in 2016. The mayor is responsible for the administration of government services, the composition of councils and committees overseeing Lahore City District departments and serves as the chairperson for meeting of Lahore Council. The mayor also functions to help devise long-term development plans in consultation with other stakeholders and bodies to improve the condition, livability, and sustainability of urban areas.

Neighbourhoods

Lahore District is a subdivision of the Punjab, and is further divided into 9 administrative zones.[167] Each town in turn consists of a group of union councils, which total to 274.[168]

|

|

Politics

The 2015 Local Government elections for Union Councils in Lahore yielded the following results:

MCL/Zones Parties |

UC seats |

|---|---|

| Pakistan Muslim League (N) | 229 |

| Independents | 27 |

| Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf | 12 |

| Pakistan Peoples Party | 1 |

| Awaiting results | *5 |

| Total | 274 |

Festivals

The people of Lahore celebrate many festivals and events throughout the year, including Islamic, traditional Punjabi, Christian, and national holidays and festivals.

Many people decorate their houses and light candles to illuminate the streets and houses during public holidays; roads and businesses may be lit for days. Many of Lahore's dozens of Sufi shrines hold annual festivals called urs to honor their respective saints. For example, the mausoleum of Ali Hujwiri at the Data Darbar shrine has an annual urs that attracts up to one million visitors per year.[170] The popular Mela Chiraghan festival in Lahore takes place at the shrine of Madho Lal Hussain, while other large urs take place at the shrines of Bibi Pak Daman, and at the Shrine of Mian Mir.[171] Eid ul-Fitr and Eid ul-Adha are celebrated in the city with public buildings and shopping centers decorated in lights. Lahoris also commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husain at Karbala during massive processions that take place during the first ten days of the month of Muharram.[172]

Basant is a traditional Punjabi festival that marks the coming of spring. Basant celebrations in Pakistan are centred in Lahore, and people from all over the country and from abroad come to the city for the annual festivities. Kite-flying competitions traditionally take place on city rooftops during Basant, while the Lahore Canal is decorated with floating lanterns. Courts have banned the kite-flying because of casualties and power installation losses. The ban was lifted for two days in 2007, then immediately reimposed when 11 people were killed by celebratory gunfire, sharp kite-strings, electrocution, and falls related to the competition.[173]

Lahore's churches are elaborately decorated for Christmas and Easter celebrations.[174] Shopping centers and public buildings also install Christmas installations to celebrate the holiday, even though Christians make up a minority of Lahore's population.[175]

Tourism

.jpg)

Lahore Fort (Shahi Qila)

Lahore Fort (Shahi Qila) Minar-e-Pakistan at night

Minar-e-Pakistan at night_main_building.jpg) Shalimar Gardens

Shalimar Gardens

Lahore remains a major tourist destination in Pakistan. The Walled City of Lahore was renovated in 2014 and is popular due to the presence of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[176] Among the most popular sights are the Lahore Fort, adjacent to the Walled City, and home to the Sheesh Mahal, the Alamgiri Gate, the Naulakha pavilion, and the Moti Masjid. The fort along with the adjoining Shalimar Gardens has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981.[177]

The city is home to several ancient religious sites including prominent Hindu temples, the Krishna Temple and Valmiki Mandir. The Samadhi of Ranjit Singh, also located near the Walled City, houses the funerary urns of the Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The most prominent religious building is the Badshahi Mosque, constructed in 1673; it was the largest mosque in the world upon construction. Another popular sight is the Wazir Khan Mosque,[178] known for its extensive faience tile work and constructed in 1635.[179]

Religious sites

Other well-known religious sites in the city are:

- St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church

- Sacred Heart Cathedral

- Badshahi Mosque

- Lava Temple

- Suneri Mosque

- Grand Jamia Mosque[180]

- Masjid of Mariyam Zamani

- Neevin Mosque

- Dai Anga Mosque

- Shab Bhar Mosque

- Wazir Khan Mosque

- Moti Masjid (Lahore Fort)

- Muhammad Saleh Kamboh Mosque

- Masjid Shuhada

- Oonchi Mosque

- Lohari Gate Mosque

- Shaheed Ganj Mosque

- Data Durbar Complex

- Grand Jamia Mosque, Lahore

- Valmiki Temple

- Krishna Mandir, Lahore

- Darbar Madho Lal Hussain

- Sacred Heart Cathedral, Lahore

Museums

- Lahore Museum

- Army Museum Lahore

- National History Museum

- Fakir Khana

- Javed Manzil

- Shakir Ali Museum

- Islamic Summit Minar

- National Museum of Science and Technology

- Tollinton Market-Lahore City Heritage Museum

Tombs

- Tomb of Ali Mardan Khan

- Tomb of Allama Iqbal

- Tomb of Anarkali

- Tomb of Asif Khan

- Tomb of Dai Anga

- Tomb of Jani Khan

- Tomb of Jahangir

- Tomb of Nadira Begum

- Tomb of Nur Jahan

- Buddhu

- Cypress Tomb or Sarowala Maqbara

- Kuri Bagh

- Mai Dai

- Mian Khan

- Nusrat Khan

- Prince Pervez

- Qutb-ud-din Aibak

- Saleh Kamboh

- Mir Niamat Khan

- Rasul Shahyun

- Gul Begam

- Malik Ayaz

- Zafar Jang Kokaltash

- Zeb-un-Nisa

Shrines

- Bibi Pak Daman

- Ali Hujwiri

- Mian Mir

- Madho Lal Hussain

- Khawaja Tahir Bandgi

- Ghazi Ilm Din Shaheed

- Sheikh Musa Ahangar

- Khawaja Mehmud

- Nizam-ud-Din

- Siraj-ud-Din Gilani

- peer makki

- Baba Shah Jamal

Samadhis

- Bhai Vasti Ram

- Ranjit Singh

- Sir Ganga Ram

- Bhai Taru Singh

Havelis

There are many havelis inside the Walled City of Lahore, some in good condition while others need urgent attention. Many of these havelis are fine examples of Mughal and Sikh Architecture. Some of the havelis inside the Walled City include:

- Mubarak Begum Haveli Bhatti Gate

- Chuna Mandi Havelis

- Haveli of Nau Nihal Singh

- Nisar Haveli

- Haveli Barood Khana

- Salman Sirhindi ki Haveli

- Dina Nath Ki Haveli

- Mubarak Haveli – Chowk Nawab Sahib, Mochi/Akbari Gate

- Lal Haveli beside Mochi Bagh

- Mughal Haveli (residence of Maharaja Ranjeet Singh)

- Haveli Sir Wajid Ali Shah (near Nisar Haveli)

- Haveli Mian Khan (Rang Mehal)

- Haveli Shergharian (near Lal Khou)

Other landmarks

Historic neighbourhoods

Education

Lahore is known as Pakistan's educational capital, with more colleges and universities than any other city in Pakistan. Lahore is Pakistan's largest producer of professionals in the fields of science, technology, IT, law, engineering, medicine, nuclear sciences, pharmacology, telecommunication, biotechnology and microelectronics, nanotechnology and the only future hyper high-tech center of Pakistan.[181] Most of the reputable universities are public, but in recent years there has also been an upsurge in the number of private universities. It has the only AACSB accredited business school in Pakistan, namely, Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). The literacy rate of Lahore is 74%. Lahore hosts some of Pakistan's oldest and best educational institutes:

- Lahore Garrison University

- Lahore University of Management Sciences, established in 1986

- St. Francis High School, established in 1842

- King Edward Medical University, established in 1860

- Forman Christian College, established in 1864

- Government College University, Lahore, established in 1864

- Convent of Jesus and Mary, established in 1867

- University Law College, established in 1868

- National College of Arts, established in 1875

- Oriental College, established in 1876

- University of the Punjab, established in 1882[182]

- University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, established in 1882

- Central Model School, established in 1883

- Aitchison College, established in 1886

- Muslim Model High School, established in 1890

- Islamia College, established in 1892

- St. Anthony's High School, established in 1892

- Sacred Heart High School, established in 1906

- Queen Mary College, established in 1908

- Dayal Singh College, established 1910

- Kinnaird College for Women University, established in 1913

- University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, established in 1921

- Lahore College for Women University, established in 1922

- Hailey College of Commerce, established in 1927

- De'Montmorency College of Dentistry, established in 1929

- Garrison College for Boys, 52-A Sarfaraz Rafiqui Road, established in 2014

- M.A.O College, established in 1933

- Lady Maclagan Training College, established in 1933

- Lady Willingdon Nursing School, established in 1933

- University College of Pharmacy, established in 1944

- Jamia Ashrafia, established in 1947

- Fatima Jinnah Medical University, established in 1948

- College of Statistical and Actuarial Sciences, established in 1950

- College of Home Economics, established in 1955

- Don Bosco High School, established in 1956

- Lahore Grammar School, established in 1979

- University of Education, established in 2002

- PakTurk International Schools and Colleges, established in 2006

- University of Management and Technology (Lahore), established in 2002

- University of Central Punjab, established in 2002

- Beaconhouse National University, established in 2003

- Lahore School of Economics, established in 1993

- Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, established in 1994

- University College Lahore, established in 1994

- University of Lahore, established in 1999

- University of Health Sciences, Lahore, established in 2002

- Lahore Medical and Dental College, established in 1997

- Aitchison College, established in 1886

Sports

- Sports venues

Pakistan playing against Argentina in 2005.

Pakistan playing against Argentina in 2005. Gaddafi Stadium is one of the largest stadiums of Pakistan with a capacity of 27,000 spectators.

Gaddafi Stadium is one of the largest stadiums of Pakistan with a capacity of 27,000 spectators.

Lahore Garrison Shooting Gallery

Lahore Garrison Shooting Gallery

Lahore has successfully hosted many international sports events including the finals of the 1990 Men's Hockey World Cup and the 1996 Cricket World Cup. The headquarters of all major sports governing bodies are located here in Lahore including Cricket, Hockey, Rugby, Football etc. and also has the head office of Pakistan Olympic Association.

Gaddafi Stadium is a Test cricket ground in Lahore. It was completed in 1959 and later in the 1990s, renovations were carried out by Pakistani architect Nayyar Ali Dada.

Lahore is home to several golf courses. The Lahore Gymkhana Golf Course, the Lahore Garrison Golf and Country Club, the Royal Palm Golf Club and newly built DHA Golf Club are well maintained Golf Courses in Lahore. In nearby Raiwind Road, a 9 holes course, Lake City, opened in 2011. The newly opened Oasis Golf and Aqua Resort is another addition to the city. It is a state-of-the-art facility featuring golf, water parks, and leisure activities such as horse riding, archery and more. The Lahore Marathon is part of an annual package of six international marathons being sponsored by Standard Chartered Bank across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. More than 20,000 athletes from Pakistan and all over the world participate in this event. It was first held on 30 January 2005, and again on 29 January 2006. More than 22,000 people participated in the 2006 race. The third marathon was held on 14 January 2007.[183] Plans exist to build Pakistan's first sports city in Lahore, on the bank of the Ravi River.[184]

- Professional sports teams from Lahore

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lahore Qalandars | Abu Dhabi T20 Trophy | Cricket | Sheikh Zayed Cricket Stadium | 2018 |

| Lahore Qalandars | Pakistan Super League | Cricket | Dubai International Cricket Stadium | 2015 |

| Lahore Lions | National T20 League/National One-day Championship | Cricket | Gaddafi Stadium | 2004 |

| Lahore Eagles | National T20 League/National One-day Championship | Cricket | Gaddafi Stadium | 2006 |

| WAPDA F.C. | Pakistan Premier League | Football | Punjab Stadium | 1983 |

Twin towns and sister cities

The following international cities have been declared twin towns and sister cities of Lahore.

.svg.png)

Awards

In 1966, the Government of Pakistan awarded a special flag, the Hilal-i-istaqlal to Lahore (also to Sargodha and Sialkot) for showing severe resistance to the enemy during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 as these cities were targets of the Indian advance.[191] Every year on Defence Day (6 September), this flag is hoisted in these cities in recognition of the will, courage and perseverance of their people.[192]

See also

- Lahore Fashion Week

- Lahore Knowledge Park

- Lahore Literary Festival

- Lahore Railway Station

- Lahori cuisine

- List of cemeteries in Lahore

- List of cities proper by population

- List of films set in Lahore

- List of hospitals in Lahore

- List of largest cities in Organisation of Islamic Cooperation member countries

- List of metropolitan areas in Asia

- List of people from Lahore

- List of streets in Lahore

- List of tallest buildings in Lahore

- List of towns in Lahore

- List of urban areas by population

- Sikh period in Lahore

- Transport in Lahore

- Walled City of Lahore

References

- "Punjab Portal". Government of Punjab. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "Population of Major Cities Census – 2017 [pdf]" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "National Dialing Codes". Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1382881

- https://www.geo.tv/amp/196173-punjab-fares-much-better-than-other-provinces-on-hdi

- "Pakistan: Provinces and Major Cities - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de.

- Lahore Cantonment, globalsecurity.org

- "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". 22 April 2008. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Shelley, Fred (16 December 2014). The World's Population: An Encyclopedia of Critical Issues, Crises, and Ever-Growing Countries. ABC-CLIO. p. 356. ISBN 978-1-61069-506-0.

Lahore is the historic center of the Punjab region of the northwestern portion of the Indian subcontinent

- Usha Masson Luther (1990). Historical Routes of North West Indian Subcontinent, Lahore to Delhi, 1550s–1850s A.D.: Network Analysis Through DCNC-micro Methodology. Sagar Publications.

- Diminishing Conflicts in Asia and the Pacific: Why Some Subside and Others Don't. Routledge. 2013. ISBN 978-0-415-67031-9. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

Lahore, perhaps Pakistan's most liberal city...

- Craig, Tim (9 May 2015). "The Taliban once ruled Pakistan's Swat Valley. Now peace has returned". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

"We now want to dress like the people of Punjab," said Abid Ibrahim, 19, referring to the eastern province that includes Lahore, often referred to as Pakistan's most progressive city.

- "Lahore attack: Pakistan PM Sharif demands swift action on terror". BBC. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

Lahore is one of Pakistan's most liberal and wealthy cities. It is Mr Sharif's political powerbase and has seen relatively few terror attacks in recent years.

- Glover, William (January 2007). Making Lahore Modern, Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. Univ of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5022-4.

- "Rising Lahore and reviving Pakistan – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 21 July 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- Kudaisya, Gyanesh; Yong, Tan Tai (2004). The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134440481. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 4 March 2005. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Zaidi, S. Akbar (15 October 2012). "Lahore's domination". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- Windsor, Antonia (22 November 2006). "Out of the rubble". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- Planet, Lonely. "Lahore, Pakistan – Lonely Planet". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities: With an Account of Its Modern Institutions, Inhabitants, Their Trade, Customs, &c. Printed at the New Imperial Press.

- Suvorova, Anna (22 July 2004). Muslim Saints of South Asia: The Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries. Routledge. ISBN 1134370059.

- al-Hamawi, Yaqut. "Mu'jam al-Buldan". http://arabiclexicon.hawramani.com/. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

لَوْهُور: بفتح أوله، وسكون ثانيه، والهاء، وآخره راء، والمشهور من اسم هذا البلد لهاور: وهي مدينة عظيمة مشهورة في بلاد الهند.

External link in|website=(help) - Journal of Central Asia. Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia, Quaid-i-Azam University. 1978.

- Boltz, William G.; Shapiro, Michael C. (1 January 1991). Studies in the Historical Phonology of Asian Languages. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027235740.

- Journal of Asian Civilisations. Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations. 2001.

- Gazetteer of the Ferozpur District: 1883. 1883.

- Haroon Khalid. "How old is Lahore? The clues lie in a blend of historical fact and expedient legend". Dawn.

A legend subsequently grew that connected the history of the city with Valmiki's Ramayana. According to this narrative, Valmiki lived on a mound on the banks of the Ravi when he hosted Ram's consort Sita after she was banished from Ayodhya. It is here that she gave birth Lav and Kush, the princes of Ayodhya, who later founded the twin cities of Lahore and Kasur.

- Bombay Historical Society (1946). Annual bibliography of Indian history and Indology, Volume 4. p. 257. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Baqir, Muhammad (1985). Lahore, past and present. B.R. Pub. Corp. pp. 19–20. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Nadiem, Ihsan N (2005). Punjab: land, history, people. Al-Faisal Nashran. p. 111. ISBN 9789695032831. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Zamir, Sufia (14 January 2018). "HERITAGE: THE LONELY LITTLE TEMPLE". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Neville, p.xii

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities: With an Account of Its Modern Institutions, Inhabitants, Their Trade, Customs, &c. Printed at the New Imperial Press.

- Charles Umpherston Aitchison (2002). Lord Lawrence and the Reconstruction of India Under the British Rule. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 54. ISBN 9788177551730.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Brill. ISBN 978-9047423836. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- unknown author from Jōzjān (1937). Hudud al-'Alam, The Regions of the World: A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. – 982 A.D. Translated by V. Minorsky. London: Oxford University Press.

- Al-Hind, the Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest, 11th–13th Centuries By André Wink

- "Dawn Pakistan – The 'shroud' over Lahore's antiquity". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- Al-Hind, the Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest, 11th–13th Centuries By André Wink PAGE 235

- Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 16, p. 106. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Andrew Petersen (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-415-06084-4.

- ".GC University Lahore". Gcu.edu.pk. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- James L. Wescoat; Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn (1 January 1996). Mughal Gardens: Sources, Places, Representations, and Prospects. Dumbarton Oaks. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-88402-235-0.

- Encyclopedia of Chronology: Historical and Biographical. Longmans, Green and Company. 1872. p. 590. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

lahore 1152.

- "Lahore" Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Once upon a time". Apnaorg.com. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander. "Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia (2 volumes): A Historical Encyclopedia" ABC-CLIO, 22 July 2011 ISBN 978-1-59884-337-8 pp 269–270

- Jackson, Peter (16 October 2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521543290. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Sadasivan, Balaji (14 August 2018). The Dancing Girl: A History of Early India. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814311670 – via Google Books.

- "isbn:8190891804 – Google Search". books.google.com.

- Neville, p.xiii

- Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 16, p. 107. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Ahmed, Farooqui Salma (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson India. ISBN 9788131732021.

- Dhillon, Dalbir Singh (1988). Sikhism Origin and Development. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231038761.

- "Short Cuts". The Economist. 19 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

For centuries Lahore was the heart of Mughal Hindustan, known to visitors as the City of Gardens. Today it has a greater profusion of treasures from the Mughal period (the peak of which was in the 17th century) than India's Delhi or Agra, even if Lahore's are less photographed.

- Chandra, Satish (2005). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part – II. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 8124110662. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (2003). Agra historical and descriptive with an account of Akbar and his court and of the modern city of Agra. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120617096. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Holt, P. M. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 2A, The Indian Sub-Continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521291372. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Pashaura Singh (2006). Life, and Work of Guru Arjan: History, Memory, and Biography in the Sikh Tradition. Oxford University Press. pp. 23, 217–218. ISBN 978-0-19-567921-2.

- "International council on monuments and sites" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- "Lahore Fort Alamgiri Gate". Asian Historical Architecture. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities. Oxford University: New Imperial Press.

- Axworthy, Michael (2010). Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-85773-347-4.

- Roy, Kaushik (2004). India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–1. ISBN 978-81-7824-109-8.

- Mehta, J.L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Tomb of Asif Khan" (PDF). Global Heritage Fund. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Pakistani Sikhs reopen temple after 73 years, retrieved 21 January 2020

- Bansal, Bobby (2015). Remnants of the Sikh Empire: Historical Sikh Monuments in India & Pakistan. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 978-9384544935.

- Kakshi, S.R.; Pathak, Rashmi; Pathak, S.R. Bakshi R. (1 January 2007). Punjab Through the Ages. Sarup & Sons. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-81-7625-738-1. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- Singh, Bhagata (1990). Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his times. Sehgal Publishers Service.

- K.S. Duggal (1989). Ranjit Singh: A Secular Sikh Sovereign. Exoticindiaart.com. ISBN 8170172446. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Pakistan – Lahore – Hindukush Karakuram Tours & Treks". Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Kartar Singh Duggal (1 January 2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-81-7017-410-3.

- Masson, Charles. 1842. Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab, 3 v. London: Richard Bentley (1) 37

- Sidhwa, Bapsi (2005). City of Sin and Splendour: Writings on Lahore. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-303166-6.

- Marshall, Sir John Hubert (1906). Archaeological Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

- Sidhwa, Bapsi (14 August 2018). City of Sin and Splendour: Writings on Lahore. Penguin Books India. ISBN 9780143031666 – via Google Books.