Punjab Province (British India)

Punjab was a province of British India. Most of the Punjab region was annexed by the East India Company in 1849, and was one of the last areas of the Indian subcontinent to fall under British control. In 1858, the Punjab, along with the rest of British India, came under the direct rule of the British crown. The province comprised five administrative divisions, Delhi, Jullundur, Lahore, Multan and Rawalpindi and a number of princely states.[1] In 1947, the partition of India led to the province being divided into East Punjab and West Punjab, in the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan respectively.

| Punjab Province | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of British India | |||||||||||||||

| 1849–1947 | |||||||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||

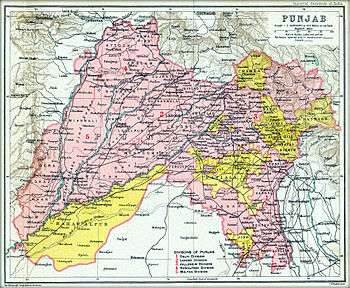

Map of British Punjab 1909 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||

| • Motto | Crescat e Fluviis "Let it grow from the rivers" | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 2 April 1849 | ||||||||||||||

| 1858 | |||||||||||||||

• North-West Frontier Province separated from Punjab | 1901 | ||||||||||||||

| 14–15 August 1947 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Etymology

The region was originally called Sapta Sindhu,[2] the Vedic land of the seven rivers flowing into the ocean.[3] The Sanskrit name for the region, as mentioned in the Ramayana and Mahabharata for example, was Panchanada which means "Land of the Five Rivers", and was translated to Persian as Punjab after the Muslim conquests.[4][5] The later name Punjab is a compound of two Persian words[6][7] Panj (five) and āb (water) and was introduced to the region by the Turko-Persian conquerors[8] of India and more formally popularised during the Mughal Empire.[9][10] Punjab literally means "(The Land of) Five Waters" referring to the rivers: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas.[11] All are tributaries of the Indus River, the Chenab being the largest.

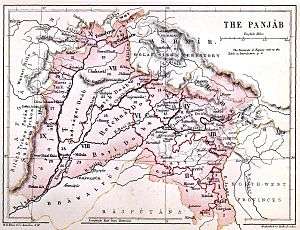

Geography

Geographically, the province was a triangular tract of country of which the Indus River and its tributary the Sutlej formed the two sides up to their confluence, the base of the triangle in the north being the Lower Himalayan Range between those two rivers. Moreover, the province as constituted under British rule also included a large tract outside these boundaries. Along the northern border, Himalayan ranges divided it from Kashmir and Tibet. On the west it was separated from the North-West Frontier Province by the Indus, until it reached the border of Dera Ghazi Khan District, which was divided from Baluchistan by the Sulaiman Range. To the south lay Sindh and Rajputana, while on the east the rivers Jumna and Tons separated it from the United Provinces.[1] In total Punjab had an area of approximately 357 000 km square about the same size as modern day Germany, being one of the largest provinces of the British Raj.

It encompassed the present day Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh, Delhi, and Himachal Pradesh (but excluding the former princely states which were later combined into the Patiala and East Punjab States Union) and the Pakistani regions of the Punjab, Islamabad Capital Territory and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

In 1901 the frontier districts beyond the Indus were separated from Punjab and made into a new province: the North-West Frontier Province.

History

Company rule

On 21 February 1849, the East India Company decisively defeated the Sikh Empire at the Battle of Gujrat bringing to an end the Second Anglo-Sikh War. Following the victory, the East India Company annexed the Punjab on 2 April 1849 and incorporated it within British India. The province whilst nominally under the control of the Bengal Presidency was administratively independent. Lord Dalhousie constituted the Board of Administration by inducting into it the most experienced and seasoned British officers. The Board was led by Sir Henry Lawrence, who had previously worked as British Resident at the Lahore Durbar and also consisted of his younger brother John Lawrence and Charles Grenville Mansel.[12] Below the Board, a group of acclaimed officers collectively known as Henry Lawrence's "Young Men" assisted in the administration of the newly acquired province. The Board was abolished by Lord Dalhousie in 1853; Sir Henry was assigned to the Rajputana Agency, and his brother John succeeded as the first Chief Commissioner.

Recognising the cultural diversity of the Punjab, the Board maintained a strict policy of non-interference in regard to religious and cultural matters.[13] Sikh aristocrats were given patronage and pensions and groups in control of historical places of worship were allowed to remain in control.[13]

During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Punjab remained relatively peaceful.[14] In May, John Lawrence took swift action to disarm potentially mutinous sepoys and redeploy most European troops to the Delhi ridge.[15] Finally he recruited new regiments of Punjabis to replace the depleted force, and was provided with manpower and support from surrounding princely states such as Jind, Patiala, Nabha and Kapurthala and tribal chiefs on the borderlands with Afghanistan. By 1858, an estimated 70,000 extra men had been recruited for the army and militarised police from within the Punjab.[14]

British Raj

In 1858, under the terms of the Queen's Proclamation issued by Queen Victoria, the Punjab, along with the rest of British India, came under the direct rule of the British crown.[16] Delhi Territory was transferred from the North-Western Provinces to the Punjab in 1858, partly to punish the city for the important role the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, and the city as a whole, played in the 1857 Rebellion.[17]

Sir John Lawrence, then Chief Commissioner, was appointed the first Lieutenant-Governor on 1 January 1859. In 1866, the Judicial Commissioner was replaced by a Chief Court. The direct administrative functions of the Government were carried by the Lieutenant-Governor through the Secretariat, comprising a Chief Secretary, a Secretary and two Under-Secretaries. They were usually members of the Indian Civil Service.[18] The territory under the Lieutenant consisted of 29 Districts, grouped under 5 Divisions, and 43 Princely States. Each District was under a Deputy-Commissioner, who reported to the Commissioner of the Division. Each District was subdivided into between three and seven tehsils, each under a tahsildar, assisted by a naib (deputy) tahsildar.[19]

In 1885 the Punjab administration began an ambitious plan to transform over six million acres of barren waste land in central and western Punjab into irrigable agricultural land. The creation of canal colonies was designed to relieve demographic pressures in the central parts of the province, increase productivity and revenues, and create a loyal support amongst peasant landholders.[20] The colonisation resulted in an agricultural revolution in the province, rapid industrial growth, and the resettlement of over one million Punjabis in the new areas.[21] A number of towns were created or saw significant development in the colonies, such as Lyallpur, Sargodha and Montgomery. Colonisation led to the canal irrigated area of the Punjab increasing from three to fourteen million acres in the period from 1885 to 1947.[22]

The beginning of the twentieth century saw increasing unrest in the Punjab. Conditions in the Chenab colony, together with land reforms such as the Punjab Land Alienation Act, 1900 and the Colonisation Bill, 1906 contributed to the 1907 Punjab unrest. The unrest was unlike any previous agitation in the province as the government had for the first time aggrieved a large portion of the rural population.[23] Mass demonstrations were organised, headed by Lala Lajpat Rai, a leader of the Hindu revivalist sect Arya Samaj.[23] The unrest resulted in the repeal of the Colonisation Bill and the end of paternalist policies in the colonies.[23]

During the First World War, Punjabi manpower contributed heavily to the Indian Army. Out of a total of 683,149 combat troops, 349,688 hailed from the province.[24] In 1918, an influenza epidemic broke out in the province, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 962,937 people or 4.77 percent of the total estimated population.[25] In March 1919 the Rowlatt Act was passed extending emergency measures of detention and incarceration in response to the perceived threat of terrorism from revolutionary nationalist organisations.[26] This led to the infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre in April 1919 where the British colonel Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to fire on a group of some 10,000 unarmed protesters and Baisakhi pilgrims.[27]

Administrative reforms

The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms enacted through the Government of India Act 1919 expanded the Punjab Legislative Council and introduced the principle of dyarchy, whereby certain responsibilities such as agriculture, health, education, and local government, were transferred to elected ministers. The first Punjab Legislative Council under the 1919 Act was constituted in 1921, comprising 93 members, seventy per cent to be elected and rest to be nominated.[28] Some of the British Indian ministers under the dyarchy scheme were Sir Sheikh Abdul Qadir, Sir Shahab-ud-Din Virk and Lala Hari Kishen Lal.[29][30]

The Government of India Act 1935 introduced provincial autonomy to Punjab replacing the system of dyarchy. It provided for the constitution of Punjab Legislative Assembly of 175 members presided by a Speaker and an executive government responsible to the Assembly. The Unionist Party under Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan formed the government in 1937. Sir Sikandar was succeeded by Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana in 1942 who remained the Premier till partition in 1947. Although the term of the Assembly was five years, the Assembly continued for about eight years and its last sitting was held on 19 March 1945.[31]

Partition

The struggle for Indian independence witnessed competing and conflicting interests in the Punjab. The landed elites of the Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities had loyally collaborated with the British since annexation, supported the Unionist Party and were hostile to the Congress party led independence movement.[32] Amongst the peasantry and urban middle classes, the Hindus were the most active National Congress supporters, the Sikhs flocked to the Akali movement whilst the Muslims eventually supported the Muslim League.[32]

Since the partition of the sub-continent had been decided, special meetings of the Western and Eastern Section of the Legislative Assembly were held on 23 June 1947 to decide whether or not the Province of the Punjab be partitioned. After voting on both sides, partition was decided and the existing Punjab Legislative Assembly was also divided into West Punjab Legislative Assembly and the East Punjab Legislative Assembly. This last Assembly before independence, held its last sitting on 4 July 1947.[33]

Demographics

The first British census of the Punjab was carried out in 1855. This covered only British territory to the exclusion of local princely states, and placed the population at 17.6 million The first regular census of British India carried out in 1881 recorded a population of 20.8 million people. The final British census in 1941 recorded 34.3 million people in the Punjab, which comprised 29 districts within British territory, 43 princely states, 52,047 villages and 283 towns.[34]

In 1881, only Amritsar and Lahore had populations over 100,000. The commercial and industrial city of Amritsar (152,000) was slightly larger than the cultural capital of Lahore (149,000). Over the following sixty years, Lahore increased in population fourfold, whilst Amritsar grew two-fold. By 1941, the province had seven cities with populations over 100,000 with emergence and growth of Rawalpindi, Multan, Sialkot, Jullundur and Ludhiana.[34]

The colonial period saw large scale migration within the Punjab due to the creation of canal colonies in western Punjab. The majority of colonists hailed from the seven most densely populated districts of Amritsar, Gurdaspur, Jullundur, Hoshiarpur, Ludhiana, Ambala and Sialkot, and consisted primarily of Jats, Arains, Sainis, Kambohs and Rajputs. The movement of many highly skilled farmers from eastern and central Punjab to the new colonies, led to western Punjab becoming the most progressive and advanced agricultural region of the province. The period also saw significant numbers of Punjabis emigrate to other regions of the British Empire. The main destinations were East Africa - Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, Southeast Asia - Malaya and Burma, Hong Kong and Canada.[34]

Religion

The Punjab was a religiously eclectic province, comprising three major groups: Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs. By 1941, the religious Muslims constituting an absolute majority at 53.2%, whilst the Hindu population was at 29.1%. The period between 1881 and 1941 saw a significant increase in the Sikh and Christian populations, growing from 8.2% and 0.1% to 14.9% and 1.9% respectively.[34] The decrease in the Hindu population has been attributed to the conversion of a number of lower caste Hindus to Islam, Sikhism and Christianity.[34]

| Religious group |

Population % 1881 |

Population % 1891 |

Population % 1901 |

Population % 1911[lower-alpha 1] |

Population % 1921 |

Population % 1931 |

Population % 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam | 47.6% | 47.8% | 49.6% | 51.1% | 51.1% | 52.4% | 53.2% |

| Hinduism | 43.8% | 43.6% | 41.3% | 35.8% | 35.1% | 30.2% | 29.1% |

| Sikhism | 8.2% | 8.2% | 8.6% | 12.1% | 12.4% | 14.3% | 14.9% |

| Christianity | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Other religions / No religion | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

Administrative divisions

| Division | Districts in British Territory / Princely States |

|---|---|

| Delhi Division | |

| Jullundur Division | |

| Lahore Division |

|

| Rawalpindi Division | |

| Multan Division | |

| Total area, British Territory | 97,209 square miles |

| Native States | |

| Total area, Native States | 36,532 square miles |

| Total area, Punjab | 133,741 square miles |

Agriculture

Within a few years of its annexation, the Punjab was regarded as British India's model agricultural province. From the 1860s onwards, agricultural prices and land values soared in the Punjab. This stemmed from increasing political security and improvements in infrastructure and communications. New cash crops such as wheat, tobacco, sugar cane and cotton were introduced. By 1920s the Punjab produced a tenth of India's total cotton crop and a third of its wheat crop. Per capita output of all the crops in the province increased by approximately 45 percent between 1891 and 1921, a growth contrasting to agricultural crises in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa during the period.[35]

An agricultural college was also established in British India, now known as University of Agriculture Faisalabad. Rapid agricultural growth, combined with access to easy credit for landowners, led to a growing crisis of indebtedness.[36] When landowners were unable to pay down their loans, urban based moneylenders took advantage of the law to foreclose debts of mortgaged land.[36] This led to a situation where land increasingly passed to absentee moneylenders who had little connection to the villages were the land was located. The colonial government recognised this as a potential threat to the stability of the province, and a split emerged in the government between paternalists who favoured intervention to ensure order, and those who opposed state intervention in private property relations.[35] The paternalists emerged victorious and the Punjab Land Alienation Act, 1900 prevented urban commercial castes, who were overwhelmingly Hindu, from permanently acquiring land from statutory agriculturalist tribes, who were mainly Muslim and Sikh.[37] Accompanied by the increasing franchise of the rural population, this interventionist approach led to a long lasting impact on the political landscape of the province. The agricultural lobby remained loyal to the government, and rejected communalism in common defence of its privileges against urban moneylenders. This position was entrenched by the Unionist Party. The Congress Party's opposition to the Act led to it being marginalised in the Punjab, reducing its influence more so than in any other province, and inhibiting its ability to challenge colonial rule locally. The political dominance of the Unionist Party would remain until partition, and significantly it was only on the collapse of its power on the eve of independence from Britain, that communal violence began to spread in rural Punjab.[35]

Army

In the immediate aftermath of annexation, the Sikh Khalsa Army was disbanded, and soldiers were required to surrender their weapons and return to agricultural or other pursuits.[13] The Bengal Army, keen to utilise the highly trained ex-Khalsa army troops began to recruit from the Punjab for Bengal infantry units stationed in the province. However opposition to the recruitment of these soldiers spread and resentment emerged from sepoys of the Bengal Army towards the incursion of Punjabis into their ranks. In 1851, the Punjab Irregular Force also known as the 'Piffars' was raised. Initially they consisted of one garrison and four mule batteries, four regiments of cavalry, eleven of infantry and the Corps of Guides, totalling approximately 13,000 men.[38] The gunners and infantry were mostly Punjabi, many from the Khalsa Army, whilst the cavalry had a considerable Hindustani presence.[38]

During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, eighteen new regiments were raised from the Punjab which remained loyal to the East India Company throughout the crisis in the Punjab and United Provinces.[39] By June 1858, of the 80,000 native troops in the Bengal Army, 75,000 were Punjabi of which 23,000 were Sikh.[40] In the aftermath of the rebellion, a thorough re-organisation of the army took place. Henceforth recruitment into the British Indian Army was restricted to loyal peoples and provinces. Punjabi Sikhs emerged as a particularly favoured martial race to serve the army.[41] In the midst of The Great Game, and fearful of a Russian invasion of British India, the Punjab was regarded of significant strategic importance as a frontier province. In addition to their loyalty and a belief in their suitability to serve in harsh conditions, Punjabi recruits were favoured as they could be paid at the local service rate, whereas soldiers serving on the frontier from more distant lands had to be paid extra foreign service allowances.[42] By 1875, of the entire Indian army, a third of recruits hailed from the Punjab.[43]

In 1914, three fifths of the Indian army came from the Punjab, despite the region constituting approximately one tenth of the total population of British India.[43] During the First World War, Punjabi Sikhs alone accounted for one quarter of all armed personnel in India.[41] Military service provided access to the wider world, and personnel were deployed across the British Empire from Malaya, the Mediterranean and Africa.[41] Upon completion of their terms of service, these personnel were often amongst the first to seek their fortunes abroad.[41] At the outbreak of the Second World War, 48 percent of the Indian army came from the province.[44] In Jhelum, Rawalpindi and Attock, the percentage of the total male population who enlisted reached fifteen percent.[45] The Punjab continued to be the main supplier of troops throughout the war, contributing 36 percent of the total Indian troops who served in the conflict.[46]

The huge proportion of Punjabis in the army meant that a significant amount of military expenditure went to Punjabis and in turn resulted in an abnormally high level of resource input in the Punjab.[47] It has been suggested that by 1935 if remittances of serving officers were combined with income from military pensions, more than two thirds of Punjab's land revenue could have been paid out of military incomes.[47] Military service further helped reduce the extent of indebtedness across the Province. In Hoshiarpur, a notable source of military personnel, in 1920 thirty percent of proprietors were debt free compared to the region's average of eleven percent.[47] In addition, the benefits of military service and the perception that the government was benevolent towards soldiers, affected the latter's attitudes towards the British.[40] The loyalty of recruited peasantry and the influence of military groups in rural areas across the province limited the reach of the nationalist movement in the province.[40]

Education

In 1854 the Punjab education department was instituted with a policy to provide secular education in all government managed institutions.[48] Privately run institutions would only receive grants-in-aid in return for providing secular instruction.[48] By 1864 this had resulted in a situation whereby all grants-in-aid to higher education schools and colleges were received by institutions under European management, and no indigenous owned schools received government help.[48]

In the early 1860s a number of educational colleges were established, including Lawrence College, Murree, King Edward Medical University, Government College, Lahore, Glancy Medical College and Forman Christian College. In 1882, Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner published a damning report on the state of education in the Punjab. He lamented the failure to reconcile government run schools with traditional indigenous schools, and noted a steady decline in the number of schools across the province since annexation.[49] He noted in particular how Punjabi Muslim's avoided government run schools due to the lack of religious subjects taught in them, observing how at least 120,000 Punjabis attended schools unsupported by the state and describing it as 'a protest by the people against our system of education.'[50] Leitner had long advocated the benefits of oriental scholarship, and the fusion of government education with religious instruction. In January 1865 he had established the Anjuman-i-Punjab, a subscription based association aimed at using a European style of learning to promote useful knowledge, whilst also reviving traditional scholarship in Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit.[51] In 1884 a reorganisation of the Punjab education system occurred, introducing measures tending towards decentralisation of control over education and the promotion of an indigenous education agency. As a consequence several new institutions were encouraged in the province. The Arya Samaj opened a college in Lahore in 1886, the Sikhs opened the Khalsa College whilst the Anjuman-i-Himayat-i-Islam stepped in to organise Muslim education.[52] In 1886 the Punjab Chiefs' College that became Aitchison College was opened to further the education of the elite classes.

Language

In 1837, Persian had been abolished as the official language of Company administration and replaced by local Indian vernacular languages. In the Sikh Empire, Persian continued to be the official state language.[53] Shortly after annexing the Punjab in 1849, the Board of Administration canvassed local officials in each of the provinces's six divisions to decide which language was "best suited for the Courts and Public Business".[54] Officials in the western divisions recommended Persian whilst eastern officials suggested a shift to Urdu.[54] In September 1849 a two language policy was instituted throughout the province. The language policy in the Punjab differed from other Indian provinces in that Urdu was not a widespread local vernacular. In 1849 John Lawrence noted "that Urdu is not the language of these districts and neither is Persian".[54]

In 1854, the Board of Administration abruptly ended the two language policy and Urdu was designated as the official language of government across the province. The decision was motivated by new civil service rules requiring all officials pass a test in the official language of their local court. In fear of potentially losing their jobs, officials in Persian districts petitioned the Board to replace Persian with Urdu, believing Urdu the easier language to master.[55] Urdu remained the official administrative language until 1947.

Officials, although aware that Punjabi was the colloquial language of the majority, instead favoured the use of Urdu for a number of reasons. Criticism of Punjabi included the belief that it was simply a form of patois, lacking any form of standardisation, and that "would be inflexible and barren, and incapable of expressing nice shades of meaning and exact logical ideas with the precision so essential in local proceedings."[56] Similar arguments had earlier been made about Bengali, Oriya and Hindustani, however those languages were later adopted for local administration. Instead it is believed the advantages of Urdu served the administration greater. Urdu, and initially Persian, allowed the Company to recruit experienced administrators from elsewhere in India who did not speak Punjabi, to facilitate greater integration with other Indian territories which were administered with Urdu, and to helped foster ties with local elites who spoke Persian and Urdu and could act as intermediaries with the wider populace.[57]

Government

Early administration

In 1849, a Board of Administration was put in place to govern the newly annexed province. The Board was led by a President and two assistants. Beneath them Commissioners acted as Superintendents of revenue and police and exercised the civil appellate and the original criminal powers of Sessions Judges, whilst Deputy Commissioners were given subordinate civil, criminal and fiscal powers.[58] In 1853, the Board of Administration was abolished, and authority was invested in a single Chief Commissioner. The Government of India Act 1858 led to further restructuring and the office of Lieutenant-Governor replaced that of Chief Commissioner.

Although The Indian Councils Act, 1861 laid the foundation for the establishment of a local legislature in the Punjab, the first legislature was constituted in 1897. It consisted of a body of nominated officials and non-officials and was presided over by the Lieutenant-Governor. The first council lasted for eleven years until 1909. The Morley-Minto Reforms led to an elected members complementing the nominated officials in subsequent councils.[59]

Punjab Legislative Council and Assembly

The Government of India Act 1919 introduced the system of dyarchy across British India and led to the implementation of the first Punjab Legislative Council in 1921. At the same time the office of lieutenant governor was replaced with that of governor. The initial Council had ninety three members, seventy per cent of which were elected and the rest nominated.[59] A president was elected by the Council to preside over the meetings. Between 1921 and 1936, there were four terms of the Council.[59]

| Council | Inaugurated | Dissolved | President(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Council | 8 Jan 1921 | 27 Oct 1923 | Sir Montagu Butler and Herbert Casson |

| Second Council | 2 Jan 1924 | 27 Oct 1926 | Herbert Casson, Sir Abdul Qadir and Sir Shahab-ud-Din Virk |

| Third Council | 3 Jan 1927 | 26 Jul 1930 | Sir Shahab-ud-Din Virk |

| Fourth Council | 24 Oct 1930 | 10 Nov 1936 | Sir Shahab-ud-Din Virk and Sir Chhotu Ram |

In 1935, the Government of India Act 1935 replaced dyarchy with increased provincial autonomy. It introduced direct elections, and enabled elected Indian representatives to form governments in the provincial assemblies. The Punjab Legislative Council was replaced by a Punjab Legislative Assembly, and the role of President with that of a Speaker. Membership of the Assembly was fixed at 175 members, and it was intended to sit for five years.[59]

First Assembly Election

The first election was held in 1937 and was won outright by the Unionist Party. Its leader, Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan was asked by the Governor, Sir Herbert Emerson to form a Ministry and he chose a cabinet consisting of three Muslims, two Hindus and a Sikh.[60] Sir Sikandar died in 1942 and was succeeded as Premier by Khizar Hayat Khan Tiwana.

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| Premier | Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan |

| Revenue Minister | Sir Sundar Singh Majithia |

| Development Minister | Sir Chhotu Ram |

| Finance Minister | Manohar Lal |

| Public Works Minister | Khizar Hayat Khan Tiwana |

| Education Minister | Mian Abdul Haye |

Second Assembly Election

The next election was held in 1946. The Muslim League won the most seats, winning 73 out of a total of 175. However a coalition led by the Unionist Party and consisting of the Congress Party and Akali Party were able to secure an overall majority. A campaign of civil disobedience by the Muslim League followed, lasting six weeks, and led to the resignation of Sir Khizar Tiwana and the collapse of the coalition government on 2 March 1947.[61] The Muslim League however were unable to attract the support of other minorities to form a coalition government themselves.[62] Amid this stalemate the Governor Sir Evan Jenkins assumed control of the government and remained in charge until the independence of India and Pakistan.[62]

Coat of arms

Crescat e Fluviis meaning, Let it grow from the rivers was the Latin motto used in the Coat of arms for Punjab Province. As per the book History of the Sikhs written by Khushwant Singh, it means Strength from the Rivers.

See also

- History of Punjab

- Punjab region

- Sikh Empire

- Sikh Confederacy

- British Raj

- Doaba Daudzai Tehsil

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 653.

- D. R. Bhandarkar, 1989, Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture: Sir WIlliam Meyers Lectures, 1938-39, Asia Educational Services, p. 2.

- A.S. valdiya, "River Sarasvati was a Himalayn-born river", Current Science, vol 104, no.01, ISSN 0011-3891.

- Yule, Henry (31 December 2018). "Hobson-Jobson: A glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive". dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu.

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (31 December 2018). "A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis Throughout". dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu.

- H K Manmohan Siṅgh. "The Punjab". The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Editor-in-Chief Harbans Singh. Punjabi University, Patiala. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 1 ("Introduction"). ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- Canfield, Robert L. (1991). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 1 ("Origins"). ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- Shimmel, Annemarie (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. London, United Kingdom: Reaktion Books Ltd. ISBN 1-86189-1857.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., vol.20, Punjab, p.107

- J. S. Grewal, The Sikhs of the Punjab, Volumes 2-3, Cambridge University Press, 8 Oct 1998, p.258

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair, Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed, A&C Black, 8 Aug 2013, p.77

- N. Arielli, B. Collins (28 November 2012). Transnational Soldiers: Foreign Military Enlistment in the Modern Era. Springer. ISBN 1137296631.

- Dalrymple, William (17 August 2009). The Last Mughal: The Fall of Delhi, 1857. A&C Black. ISBN 1408806886.

- Hibbert 2000, p. 221

- Gupta, Narayani. 1981. Delhi Between Two Empires, 1803-1931. Oxford University Press, p.26

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 20, page 331 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library". uchicago.edu.

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 20, page 333 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library". uchicago.edu.

- Imran Ali, THE PUNJAB CANAL COLONIES, 1885-1940, 1979, The Australian National University, Canberra, p34

- Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India, Routledge, 16 Dec 2013, p,55

- Saiyid, the Muslim Women of the British Punjab, p.4.

- Barrier, N. Gerald. "The Punjab Disturbances of 1907: The Response of the British Government in India to Agrarian Unrest." Modern Asian Studies, vol. 1, no. 4, 1967, pp. 353–383

- Tan Tai Yong, "An Imperial Home Front: Punjab and the First World War", The Journal of Military History (2000), p.64

- "Influenza in India, 1918." Public Health Reports (1896-1970), vol. 34, no. 42, 1919, pp. 2300–2302

- Sarkar 1921, p. 137

- "Punjab". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- http://www.pap.gov.pk/uploads/previous_members/S-1921-1923.htm Provincial Assembly of the Punjab

- The Working Of Dyarchy In India 1919 1928. D.B.Taraporevala Sons And Company.

- http://www.pap.gov.pk/uploads/previous_members/S-1924-1926.htm Provincial Assembly of the Punjab

- http://www.pap.gov.pk/uploads/previous_members/S-1937-1945.htm Provincial Assembly of the Punjab

- Pritam Singh, Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy, Routledge, 19 Feb 2008, p.54

- http://www.pap.gov.pk/uploads/previous_members/S-1946-1947.htm Provincial Assembly of the Punjab

- Krishan, Gopal (2004). "Demography of the Punjab (1849–1947)" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 11 (1): 77–89.

- Talbot, Ian A. (2007). "Punjab Under Colonialism: Order and Transformation in British India" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 14 (1): 3–10.

- Islam, M. Mufakharul. "The Punjab Land Alienation Act and the Professional Moneylenders." Modern Asian Studies 29, no. 2

- Robert W. Stern, Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p.53

- Septimus Smet Thorburn, The Punjab in Peace and War, William Blackwood and Sons (1904), p.293

- Harsh V. Pant, Handbook of Indian Defence Policy: Themes, Structures and Doctrines, Routledge, 6 Oct 2015, p.18

- Rajit K. Mazumder, The Indian Army and the Making of Punjab, Orient Blackswan, 2003, p.3

- Robin Cohen, The Cambridge Survey of World Migration - "Darshan Singh Tatla - Sikh free and military migration during the colonial period", Cambridge University Press, 2 Nov 1995, p.69

- Ian Talbot, British Rule in the Punjab, page 207

- Ian Talbot, Punjab and the Raj, 1988, page 41

- Kalim Siddiqui, Conflict, Crisis and War in Pakistan, Springer, 18 Jun 1972, p.92

- Tan Tai Yong, The Garrison State: Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, 1849-1947,, SAGE Publications India, 7 Apr 2005, p.291

- Tan Tai Yong, The Garrison State: Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, 1849-1947, SAGE Publications India, 7 Apr 2005, p.291

- Rajit K. Mazumder, The Indian Army and the Making of Punjab, Orient Blackswan, 2003, p.23

- Robert Ivermee, Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830–1910, Routledge, 28 Jul 2015, p.96

- Gottlieb William Leitner, History of indigenous education in the Punjab since annexation and in 1882, Republican Books, 1882

- Robert Ivermee, Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830–1910, Routledge, 28 Jul 2015, p.97

- Robert Ivermee, Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830–1910, Routledge, 28 Jul 2015, p.91

- Robert Ivermee, Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830–1910, Routledge, 28 Jul 2015, p.105

- Goud and Mookherjee, R. Sidda and Manisha (20 April 2014). India and Iran in Contemporary Relations. Allied Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 8184249098.

- Mir, Farina (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. pp. 35–50. ISBN 0520262697.

- Mir, Farina (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. pp. 37–50. ISBN 0520262697.

- Mir, Farina (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. pp. 37–50. ISBN 0520262697.

- Mir, Farina (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. pp. 37–50. ISBN 0520262697.

- Panjab Administration Report, p.24

- The Punjab Parliamentarians 1897-213, Provincial Assembly of the Punjab, Lahore - Pakistan, 2015

- Bakhshish Singh Nijjar, History of the United Panjab, Volume 3, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, 1 Jan 1996, p.159

- David P Forsythe, Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 1, OUP USA, 27 Aug 2009, p.49

- Lionel Knight, Britain in India, 1858–1947, Anthem Press, 1 Nov 2012, p.154

- Delhi district is made into a separate territory