Badshahi Mosque

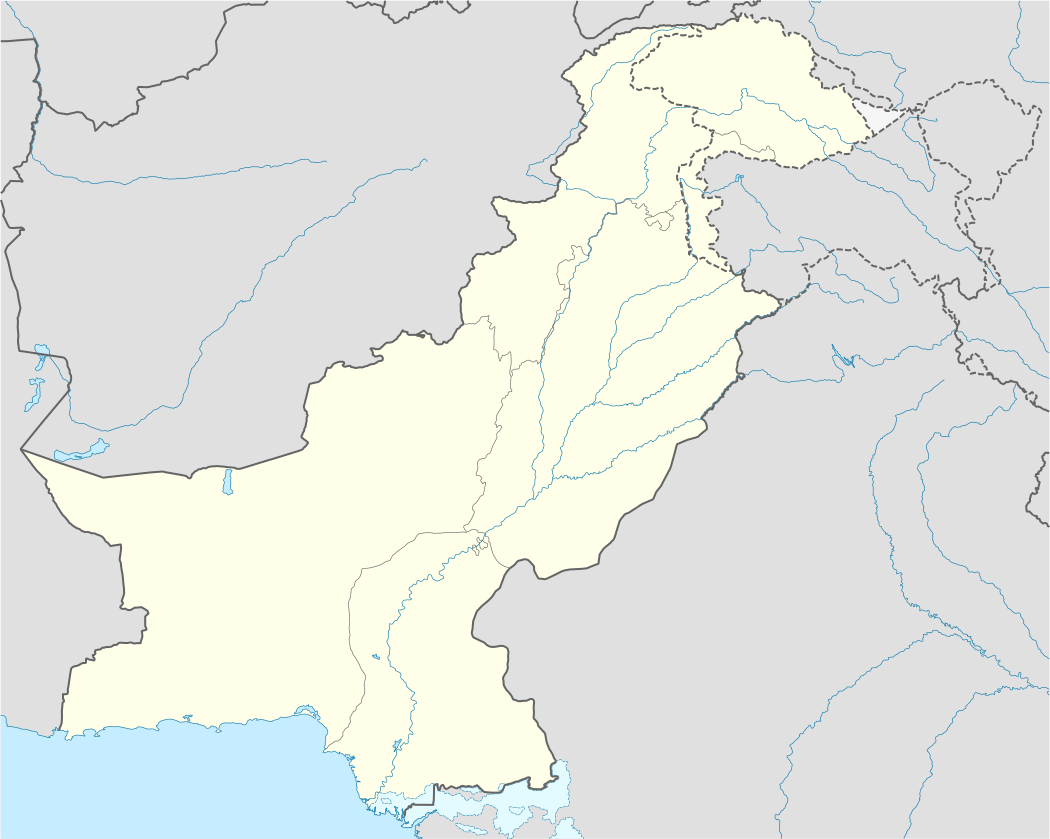

The Badshahi Mosque (Punjabi and Urdu: بادشاہی مسجد, or "Imperial Mosque") is a Mughal era mosque in Lahore, capital of the Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan.[1] The mosque is located west of Lahore Fort along the outskirts of the Walled City of Lahore,[2] and is widely considered to be one of Lahore's most iconic landmarks.[3]

| Badshahi Mosque بادشاہی مسجد | |

|---|---|

The mosque's main chamber | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Country | |

Location in Lahore, Pakistan  Badshahi Mosque (Pakistan) | |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°35′17″N 74°18′36″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Indo-Islamic, Mughal |

| Completed | 1673 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 100,000 |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Minaret(s) | 8 (4 major, 4 minor) |

| Minaret height | 176 ft 4 in (53.75 m) |

| Materials | Red sandstone, marble |

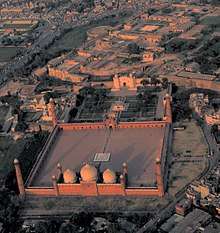

The Badshahi Mosque was built by Emperor Aurangzeb in 1671, with construction of the mosque lasting for two years until 1673. The mosque is an important example of Mughal architecture, with an exterior that is decorated with carved red sandstone with marble inlay. It remains the largest mosque of the Mughal-era, and is the second-largest mosque in Pakistan.[4] After the fall of the Mughal Empire, the mosque was used as a garrison by the Sikh Empire and the British Empire, and is now one of Pakistan's most iconic sights.

Location

The mosque is located adjacent to the Walled City of Lahore, Pakistan. The entrance to the mosque lies on the western side of the rectangular Hazuri Bagh, and faces the famous Alamgiri Gate of the Lahore Fort, which is located on the eastern side of the Hazuri Bagh. The mosque is also located next to the Roshnai Gate, one of the original thirteen gates of Lahore, which is located to the southern side of the Hazuri Bagh.[5]

Near the entrance of the mosque lies the Tomb of Muhammad Iqbal, a poet widely revered in Pakistan as the founder of the Pakistan Movement which led to the creation of Pakistan as a homeland for the Muslims of British India.[6] Also located near the mosque's entrance is the tomb of Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, who is credited for playing a major role in preservation and restoration of the mosque.[7]

Background

The sixth Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb, chose Lahore as the site for his new imperial mosque. Aurangzeb, unlike the previous emperors, was not a major patron of art and architecture and instead focused, during much of his reign, on various military conquests which added over 3 million square kilometres to the Mughal realm.[8]

The mosque was built to commemorate Aurangzeb's military campaigns in southern India, in particular against the Maratha king Shivaji.[4] As a symbol of the mosque's importance, it was built directly across from the Lahore Fort and its Alamgiri Gate, which was concurrently built by Aurangzeb during construction of the mosque.

History

Construction

The mosque was commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1671, with construction overseen by the Emperor's foster brother, and Governor of Lahore, Muzaffar Hussein - also known by the name Fidai Khan Koka.[9] Aurangzeb had the mosque built in order to commemorate his military campaigns against the Maratha king Chhatrapati Shivaji.[4] After only two years of construction, the mosque was opened in 1673.

Sikh era

On 7 July 1799, the Sikh army of Ranjit Singh took control of Lahore.[10] After the capture of the city, Maharaja Ranjit Singh used its vast courtyard as a stable for his army horses, and its 80 Hujras (small study rooms surrounding the courtyard) as quarters for his soldiers and as magazines for military stores.[11] In 1818, he built a marble edifice in the Hazuri Bagh facing the mosque, known as the Hazuri Bagh Baradari,[12] which he used as his official royal court of audience.[13] Marble slabs for the baradari may have been plundered by the Sikhs from other monuments in Lahore.[14]

During the First Anglo-Sikh War in 1841, Ranjit Singh's son, Sher Singh, used the mosque's large minarets for placement of zamburahs or light guns which were used to bombard the supporters of Chand Kaur, who had taken refuge in the besieged Lahore Fort. In one of these bombardments, the fort's Diwan-e-Aam (Hall of Public Audience) was destroyed, but was subsequently rebuilt in the British era.[2] During this time, Henri de La Rouche, a French cavalry officer employed in the army of Sher Singh,[15] also used a tunnel connecting the Badshahi mosque to the Lahore fort to temporarily store gunpowder.[16]

In 1848, the Samadhi of Ranjit Singh was built for the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh at a site immediately adjacent to the mosque after his death.

British Rule

In 1849 the British seized control of Lahore from the Sikh Empire. During the British Raj, the mosque and the adjoining fort continued to be used as a military garrison. The 80 cells built into the walls surrounding its vast courtyard were demolished by the British after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, so as to prevent them from being used for anti-British activities. The cells were replaced by open arcades known as dalans.[17]

Because of increasing Muslim resentment against the use of the mosque as a military garrison, the British set up the Badshahi Mosque Authority in 1852 to oversee the restoration and to re-establish it as a place of religious worship. From then onwards, piecemeal repairs were carried out under the supervision of the Badshahi Mosque Authority. The building was officially handed back to the Muslim community by John Lawrence, who was the Viceroy of India.[18] The building was then re-established as a mosque.

In April 1919, after the Amritsar Massacre, a mixed Sikh, Hindu and Muslim crowd of an estimated 25,000-35,000 gathered in the mosque's courtyard in protest. A speech by Gandhi was read at the event by Khalifa Shuja-ud-Din, who would later become Speaker of the Provincial Assembly of the Punjab.[19][20]

Extensive repairs commenced from 1939 onwards, when Sikandar Hayat Khan began raising funds for this purpose.[21] Renovation was supervised by the architect Nawab Alam Yar Jung Bahadur.[22] As Khan was largely credited for extensive restorations to the mosque, he was buried adjacent to the mosque in the Hazuri Bagh.

Post-independence

Restoration works begun in 1939 continued after the Independence of Pakistan, and were completed in 1960 at a total cost of 4.8 million Rupees.[22]

On the occasion of the 2nd Islamic Summit held at Lahore on 22 February 1974, thirty-nine heads of Muslim states offered their Friday prayers in the Badshahi Mosque, including, among others, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan, Faisal of Saudi Arabia, Muammar Gaddafi, Yasser Arafat, and Sabah III Al-Salim Al-Sabah of Kuwait. The prayers were led by Mawlānā Abdul Qadir Azad, the then khatib of the mosque.[23]

In 1993, the Badshahi Mosque in a tentative list as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[24] In 2000, the marble inlay in the main prayer hall was repaired. In 2008, replacement work on the red sandstone tiles on the mosque's large courtyard was begun using red sandstone imported from the original Mughal source near Jaipur, in the Indian state of Rajasthan.[25][26]

Architecture

As a gateway to the west, and Persia in particular, Lahore had a strong regional style which was heavily influenced by Persian architectural styles. Earlier mosques, such as the Wazir Khan Mosque, were adorned in intricate kashi kari, or Kashan style tile work,[4] from which the Badshahi Mosque would depart. Aurangzeb chose an architectural plan similar to that of Shah Jehan's choice for the Jama Masjid in Delhi, though built the Badshahi mosque on a much larger scale.[27] Both mosques feature red sandstone with white marble inlay, which is a departure from typical mosque design in Lahore, in which decoration is done by means of intricate tile work.[28]

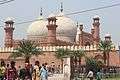

Entryway of the complex

Entrance to the mosque complex is via a two-storey edifice built of red sandstone which is elaborately decorated with framed and carved paneling on each of its facades.[24] The edifice features a muqarna, an architectural feature from the Middle East that was first introduced into Mughal architecture with construction of the nearby and ornate Wazir Khan Mosque.

The mosque's full name "Masjid Abul Zafar Muhy-ud-Din Mohammad Alamgir Badshah Ghazi" is written in inlaid marble above the vaulted entrance.[29] The mosque's gateway faces east towards the Alamgiri Gate of the Lahore Fort, which was also commissioned by Aurangzeb. The massive entrance and mosque are situated on a plinth, which is ascended by a flight of 22 steps at the mosque's main gate which.[30] The gateway itself contains several chambers which are not accessible to the public. One of the rooms is said to contain hairs from the Prophet Muhammad's, and that of his son-in-law Ali.[31]

Courtyard

After passing through the massive gate, an expansive sandstone paved courtyard spreads over an area of 276,000 square feet, and which can accommodate 100,000 worshipers when functioning as an Idgah.[30] The courtyard is enclosed by single-aisled arcades.

Prayer hall

The main edifice at the site was also built from red sandstone, and is decorated with white marble inlay.[24] The prayer chamber has a central arched niche with five niches flanking it which are about one third the size of the central niche. The mosque has three marble domes, the largest of which is located in the centre of the mosque, and which is flanked by two smaller domes.[29]

Both the interior and exterior of the mosque are decorated with elaborate white marble carved with a floral design common to Mughal art. The carvings at Badshahi mosque are considered to be uniquely fine and unsurpassed works of Mughal architecture.[24] The chambers on each side of the main chamber contains rooms which were used for religious instruction. The mosque can accommodate 10,000 worshippers in the prayer hall.[6]

Minarets

At each of the four corners of the mosque, there are octagonal, three-storey minarets made of red sandstone that are 196 feet (60 m) tall, with an outer circumference of 67 feet and the inner circumference is eight and half feet. Each minaret is topped by a marble canopy. The main building of the mosque also features an additional four smaller minarets at each corner of the building.

Gallery

- The ceiling of the prayer hall is embellished with elegant floral frescoes and Middle-Eastern style muqarnas.

The mosque features intricate Mughal frescoes.

The mosque features intricate Mughal frescoes. Entry gateway, as viewed from the mosque's courtyard

Entry gateway, as viewed from the mosque's courtyard Silhouette of the mosque's architectural elements

Silhouette of the mosque's architectural elements- Badshahi Masjid

The mosque's southern view from Fort Street

The mosque's southern view from Fort Street The interior of the mosque is embellished with intricate floral motifs.

The interior of the mosque is embellished with intricate floral motifs. An example of Badshahi Mosque's intricate decoration.

An example of Badshahi Mosque's intricate decoration.- The Tomb of Allama Iqbal is located immediately north of the mosque's monumental gateway

Light fixtures at the mosque

Light fixtures at the mosque.jpg) An evening view of the Badshahi Mosque.

An evening view of the Badshahi Mosque. The mosque at night

The mosque at night- Side view

- A view over the mosque's marble domes.

A view of Badshahi Mosque from the Alamgiri Gate.

A view of Badshahi Mosque from the Alamgiri Gate. The mosque's entry gateway connects the mosque to the Hazuri Bagh

The mosque's entry gateway connects the mosque to the Hazuri Bagh Entry gate's design

Entry gate's design- View from Iqbal Park

Panoramic view of Badshahi Mosque as seen from Food Street Fort Road

Panoramic view of Badshahi Mosque as seen from Food Street Fort Road

Further reading

- Asher, Catherine B., Architecture of Mughal India: The New Cambridge History of India Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Chugtai, M.A., Badshahi Mosque, Lahore: Lahore, 1972.

- Gascoigne, Bamber, The Great Mughals, New York: Harper & Row, 1971.

- Koch, Ebba, Mughal Architecture, Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1992.

References

- "Lahore's iconic mosque stood witness to two historic moments where tolerance gave way to brutality".

- "Badshahi Masjid". Ualberta.ca. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- "Holiday tourism: Hundreds throng Lahore Fort, Badshahi Masjid - The Express Tribune". 9 October 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Meri, Joseph (31 October 2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 91.

- Waheed ud Din, p.14

- Waheed Ud Din, p.15

- IH Malik Sikandar Hayat Khan: A Biography Islamabad: NIHCR, 1984. p 127

- "Badshahi Mosque, Lahore". Architecture Courses. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Meri, p.91

- "Welcome to the Sikh Encyclopedia". Thesikhencyclopedia.com. 14 April 2012. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Sidhwa, Bapsi (1 January 2005). "City of Sin and Splendour: Writings on Lahore". Penguin Books India. Retrieved 10 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- Tikekar, p. 74

- Khullar, K. K. (1980). Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Hem Publishers. p. 7.

- Marshall, Sir John Hubert (1906). Archaeological Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing.

- "De La Roche, Henri Francois Stanislaus". allaboutsikhs.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Grey, C. (1993). European Adventures of Northern India. Asian Educational Services. p. 343. ISBN 978-81-206-0853-5.

- Development of mosque Architecture in Pakistan by Ahmad Nabi Khan, p.114

- Amin, Agha Humayun. "Political and Military Situation from 1839 to 1857". Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Lloyd, Nick (30 September 2011). The Amritsar Massacre: The Untold Story of One Fateful Day. I.B.Tauris.

- Note: Reports on the Punjab Disturbances April 1919 gives a figure of 25,000

- Omer Tarin, Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan and the Renovation of the Badshahi Mosque, Lahore: An Historical Survey, in Pakistan Historical Digest Vol 2, No 4, Lahore, 1995, pp. 21-29

- "Badshahi Mosque (built 1672–74)". Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- "Report on Islamic Summit, 1974 Pakistan, Lahore, February 22–24, 1974", Islamabad: Department of Films and Publications, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Auqaf and Haj, Government of Pakistan, 1974 (p. 332)

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Badshahi Mosque, Lahore – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- "Badshahi Mosque Re-flooring". Archpresspk.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- "Badshahi Mosque". Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Akhter, p.270

- "Badshahi Masjid". Archnet. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Meri, p.92

- Tikekar, p.73

- Black, p.21

Notes

- Josef W. Meri. Medieval Islamic Civilization. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0415966914.

- Maneesha Tikekar. Across the Wagah. Bibliophile South Asia. ISBN 8185002347.

- Carolyn Black. Pakistan: The culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. ISBN 0778793486.

- Waheed Ud Din. The Marching Bells: A Journey of a Life Time. Author House. ISBN 9781456744144.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Badshahi Mosque. |

.jpg)