Livingston Island

Livingston Island (Russian name Smolensk,[1][2] 62°36′S 60°30′W) is an Antarctic island in the Southern Ocean, part of the South Shetlands Archipelago. It was the first land discovered south of 60° south latitude in 1819, a historic event that marked the end of a centuries-long pursuit of the mythical Terra Australis Incognita and the beginning of the exploration and utilization of real Antarctica. The name Livingston, although of unknown derivation, has been well established in international usage since the early 1820s.

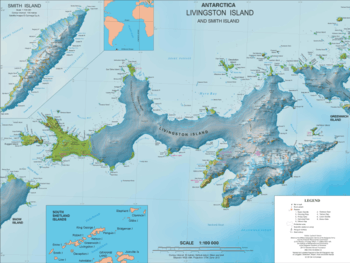

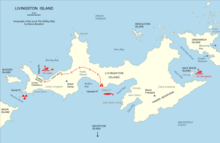

Map of Livingston Island | |

Livingston Location in the South Shetland Islands  Livingston Location in Antarctica | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Antarctica |

| Coordinates | 62°36′S 60°30′W |

| Archipelago | South Shetland Islands |

| Area | 798 km2 (308 sq mi) |

| Length | 73 km (45.4 mi) |

| Width | 36 km (22.4 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,700.2 m (5,578.1 ft) |

| Highest point | Mt Friesland |

| Administration | |

| Administered under the Antarctic Treaty System | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | ca. 80 (summer only) |

| Pop. density | 0.1/km2 (0.3/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Spaniards, Bulgarians, Chileans, Americans and Argentines |

| Highest elevation entry refers to the maximum value recorded, which is subject to possible variation as the island's highest summits are ice-covered. | |

Geography

Livingston Island is situated in West Antarctica 110 km (68 mi) northwest of Cape Roquemaurel on the Antarctic mainland, 809 km (503 mi) south-southeast of Cape Horn in South America, 796 km (495 mi) southeast of the Diego Ramírez Islands (the southernmost land of South America), 1,063 km (661 mi) due south of the Falkland Islands, 1,571 km (976 mi) southwest of South Georgia Islands, and 3,040 km (1,889 mi) from the South Pole.[3]

The island is part of the South Shetlands archipelago, an islands chain extending 510 km (317 mi) in east-northeast to west-southwest direction, and separated from the nearby Antarctic Peninsula by Bransfield Strait, and from South America by the Drake Passage. The South Shetlands cover a total land area of 3,687 km2 or 1,424 sq mi (late 20th-century estimate; the current figure might be somewhat less than that due to coastal change), comprising (from east to west) the eleven principal islands of Clarence, Elephant, King George, Nelson, Robert, Greenwich, Livingston, Deception, Snow, Low and Smith, and a number of minor islands, islets and rocks.

Livingston is separated from neighbouring Greenwich Island to the east by the 3.3 km (2.1 mi) wide McFarlane Strait, and from Snow Island to the west-southwest by the 5.9 km (3.7 mi) wide Morton Strait. Deception Island, situated in Bransfield Strait barely 18 km (11.2 mi) southwest of Livingston's Barnard Point, is an active volcano last erupting in 1967, 1969 and 1970[4] whose flooded caldera forms the 9.8 km (6 mi) by 6.8 km (4 mi) sheltered harbour of Port Foster entered by a single 540 metres (590 yards) wide passage known as Neptune's Bellows. There are several extinct volcanoes on Livingston Island itself that were active in the Quaternary, such as Rezen Knoll, Gleaner Heights, Edinburgh Hill and Inott Point.[5]

The island extends 73 km (45 mi) from Start Point in the west to Renier Point in the east, its width varying from 5 km (3.1 mi) at the neck between South Bay and Hero Bay to 36 km (22 mi) between Botev Point to the south and Williams Point to the north. Livingston is the second largest island in the archipelago after King George, with surface area of 798 km2 or 308 sq mi (early 21st-century estimate; the current figure might be somewhat smaller due to coastal change).[6][7]

The coastline is irregular, with major indentations such as South Bay, False Bay, Moon Bay, Hero, Barclay, New Plymouth, Osogovo and Walker, and peninsulas such as Hurd (10 km or 6.2 mi long), Rozhen (9 km or 5.6 mi), Burgas (10.5 km or 6.5 mi), Varna (13 km or 8.1 mi), Ioannes Paulus II (12.8 km or 8.0 mi) and Byers (15 km or 9.3 mi).[3] There are many islets and rocks lying in the surrounding waters, particularly off the north coast. More sizable among the adjacent minor islands are Rugged Island off Byers Peninsula, Half Moon Island in Moon Bay, Desolation Island in Hero Bay, and Zed Islands off Williams Point.

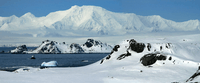

Ice cliffs, often withdrawing during recent decades to uncover new coves, beaches, spits, points and minor islands, form most of the coastline. Except for the ice-free Byers Peninsula and some isolated patches, the land surface is covered by an ice cap with ice domes and plateaus in the central and western areas, and a number of valley glaciers formed by the more mountainous relief of eastern Livingston. Certain areas of the ice cap, especially near glacier termini or over steeper slopes, are densely crevassed and almost inaccessible without specialized equipment. Elsewhere, the surface is smooth, hard and comfortable for walking, skiing or snowmobiling. However, the danger of falling into some hidden crevasse masked by a snow bridge is ever-present, including in frequently visited and supposedly well-known localities. Protracted periods of warmer weather tend to make the snow bridges more unstable and hazardous.[3]

Typical of the island's glaciology are the conspicuous ash layers originating from volcanic activity on neighbouring Deception Island.[8] The island hosts also several rock glaciers consisting of rock debris frozen in ice, such as those at Nusha Hill, MacKay Peak and Renier Point.[9]

Along with the extensive Byers Peninsula (60.35 km2 or 23 sq mi) forming the west extremity of Livingston, the ice-free part of the island includes some minor coastal areas at Cape Shirreff, Siddins Point, Hannah Point, Williams Point, Hurd Peninsula and Rozhen Peninsula, as well as slopes in the mountain ranges, and ridges and heights in eastern Livingston that are too precipitous to keep snow. Numerous meltwater streams flow in the ice-free areas during summer, extending from hundreds of meters up to 4.5 km. Byers Peninsula alone has more than 60 such streams and as many lakes, notably Midge Lake (587 by 112 m, or 642 by 122 yd), Limnopolar Lake and Basalt Lake.[10] Several such streams, lakes and ponds are situated in the vicinity of the Bulgarian and Spanish bases on Hurd Peninsula.

The principal mountain formations on the island comprise Tangra Mountains (32 kilometres or 20 miles long and 8.5 kilometres or 5.3 miles wide, with Mt Friesland rising to 1,700.2 m or 5,578 ft[11][12]), Bowles Ridge (6.5 km or 4 mi long, elevation 822 m or 2,697 ft), Vidin Heights (8 km or 5 mi, 604 m or 1,982 ft), Burdick Ridge (773 m or 2,536 ft), Melnik Ridge (696 m or 2,283 ft) and Pliska Ridge (667 m or 2,188 ft) in the eastern part of the island, and Oryahovo Heights (6 km or 4 mi, 340 m or 1,115 ft), and Dospey Heights (6 km or 4 mi, 265 m or 869 ft).[3] The local ice relief is prone to change; in December 2016 the elevations of Mount Friesland and St. Boris Peak were 1,693 m (5,554 ft) and 1,699 m (5,574 ft) respectively, making the latter the summit of Livingston in that season.[13] According to the American high accuracy Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA), Mount Friesland is 8 m (26 ft) higher than St. Boris Peak.[14]

The first ascent of the island's summit Mount Friesland was made by the Catalans Francesc Sàbat and Jorge Enrique from Juan Carlos I Base on 30 December 1991.[12][15] Of the other notable peaks of Tangra Mountains, Lyaskovets (1,473 m or 4,833 ft) was first summited by the Bulgarians Lyubomir Ivanov and Doychin Vasilev from Camp Academia on 14 December 2004,[15][16][17] Great Needle Peak (Falsa Aguja Peak, 1,679.5 m or 5,510 ft) – by the Bulgarians Doychin Boyanov, Nikolay Petkov and Aleksander Shopov from Camp Academia on 8 January 2015,[18] St. Boris – by Boyanov and Petkov from Camp Academia on 22 December 2016,[13] and Simeon (1,580 m or 5,184 ft) – by Boyanov, Petkov and Nedelcho Hazarbasanov from Nesebar Gap on 15 January 2017.[13]

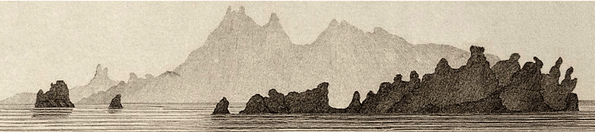

Of the island's nature, Captain Robert Fildes of the sealers Cora and Robert (both of them shipwrecked in the South Shetlands) wrote in 1821:

On advancing from the northward toward Livingston's or the Main Island, the land will appear in mountains of a vast height, and covered entirely with snow; the base of them terminating in perpendicular ice cliffs. The whole has an awfully grand, though terrific and desolate, appearance; the snowy mountains showing themselves, one over another, far above the clouds, and exciting in the mind a devotional reverence on the wonders of the Almighty: and even if surrounded on all sides with rocks and breakers, the mind is forced into pious contemplation on the grandeur of the scene.[19]

Climate

The climate of Livingston is polar tundra under the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system. Climatic conditions are influenced by the following specific factors: the island's location in the narrowest part of the Southern Ocean (less than 600 km between the Antarctic Convergence and the Antarctic Peninsula); the relatively small amplitude of water temperatures in the surrounding sea; the local relief including Tangra Mountains, one of the highest mountain ranges in the archipelago that contributes to shaping the local atmospheric circulation; and the ice cap of the island.[20] Surface air temperature decreases with increasing altitudes, which in the interior of eastern Livingston Island reach 550 m at the centrally located Wörner Gap and over 1400 m at the crest of Tangra Mountains.

The local variety of the Antarctic Peninsula weather is particularly changeable, windy, humid and sunless. Says Australian mountaineer Damien Gildea who climbed in the area: ‘Livingston got just about the worst weather in the world’.[21] A US seasonal field camp on Byers Peninsula was wrecked by storm and emergency evacuated in February 2009.[22] Whiteouts are common, and blizzards can occur at any time of the year. Temperatures are rather constant, with diurnal temperature variations seldom exceeding a few degrees. Wind chill temperatures could be up to 5 to 10 °C (9 to 18 °F) lower than actual ones. The highest daily temperature recorded on the island is 19.9 °C or 67.8 °F (measured at the Chilean Base), and the lowest is −22.4 °C or −8.3 °F (at the Spanish base).

Following a period of warming during the second half of the 20th century, the Antarctic Peninsula region has experienced a period of cooling in the early 21st century. For Livingston Island this cooling has reached 0.8 °C (1.4 °F) over the 12-year period 2004–2016, and 1 °C (1.8 °F) for the summer average temperatures over the same period. That has resulted in a longer snow cover duration in the coastal ice-free areas,[23] which could be exemplified by comparing the January snow line configurations shown on the 1996 and 2016 maps of the Bulgarian base.[24]

It can rain or snow on Livingston Island at any time of the year, although in the winter most precipitation occurs in the form of snow.[25]

| Climate data for Juan Carlos I Antarctic Base (12 m AMSL), 1988–2007 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

0.3 (32.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.2 (26.2) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44.8 (1.76) |

58.5 (2.30) |

47.3 (1.86) |

43.0 (1.69) |

29.3 (1.15) |

10.1 (0.40) |

4.0 (0.16) |

7.7 (0.30) |

17.6 (0.69) |

45.3 (1.78) |

30.8 (1.21) |

38.8 (1.53) |

377.2 (14.85) |

| Average precipitation days | 16 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 148 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 83 | 80 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 78 | 80 | 79 | 81.4 |

| Source: IPY[25] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Charles Darwin, 23 years old as he started his biological research in neighbouring Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and the Falklands in 1832, noted (with some inaccuracy in his distances):

The South Shetland Islands, in the same latitude as the southern half of Norway, possess only some lichens, moss, and a little grass with frozen under-soil within 360 miles of the forest-clad islands near Cape Horn.[26]

The coastal areas of Livingston Island are home to a selection of vegetation and animal life typical for the northern Antarctic Peninsula region, including fur, elephant, Weddell, and leopard seals, and chinstrap, gentoo, Adélie and macaroni penguins. Several other seabirds, including skuas, southern giant petrel and Antarctic terns, nest on the island during the summer months.

Spanish biological research has identified 110 species of lichens and 50 of mosses on a territory of just 3 km2 (1.2 sq mi) at the Spanish base on Hurd Peninsula, the highest species diversity recorded from any single Antarctic locality.[27]

History

It was only during the nineteenth century that any land was discovered in what is now the ‘political’ territory of Antarctica, and that land happened to be Livingston Island. The English merchant William Smith in his brig Williams, while sailing to Valparaíso in early 1819, strayed from his route south of Cape Horn and on 19 February sighted Williams Point, the northeast extremity of Livingston. That was the first land ever discovered south of 60° south latitude, in what is now the Antarctic Treaty area.[28]

Russian explorer von Bellingshausen commented on Smith's discovery:

It is noteworthy that navigation round Fire Land spanned over two hundred years, yet no one saw the coasts of New Shetland. In 1616 the Dutch mariners Lemaire and Schouten found a strait between Fire Land and Staten Land named after Lemaire. Having sailed that strait and rounded Fire Land, they were the first to enter the Great Ocean by that route. Since that time ships rounding Fire Land not infrequently encountered prolonged and strong northwesterly headwinds and storms, and probably were carried close to the South Shetland, and some, perhaps, lost their life at its coasts, but it was not until February 1819 that these islands were accidentally discovered by Smith, the captain of an English merchant brig.[29]

A few months later Smith revisited the South Shetlands, landed on King George Island on 16 October 1819 and claimed possession for Britain. In the meantime, a Spanish man-of-war had been damaged by severe weather in the Drake Passage and sank off the north coast of Livingston on 4 September 1819. The 74-gun ship San Telmo commanded by Captain Joaquín Toledo was the flagship of a Spanish naval squadron en route to Callao to fight the independence movement in Spanish America.[30] The officers, soldiers and sailors on board the ship, including the squadron's Peruvian-born leader Brigadier Rosendo Porlier, are the first recorded people to die in Antarctica. While no one survived, some of her spars and her anchor-stock were found subsequently by sealers on Half Moon Beach at Cape Shirreff.[31][28]

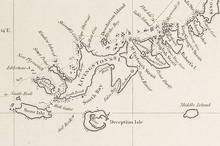

During December 1819 William Smith was back with his ship to the South Shetlands. This time he was chartered by Captain William Shirreff, British commanding officer in the Pacific stationed in Chile, and accompanied by Lieutenant Edward Bransfield who was tasked to survey and map the new lands. On 30 January 1820 they sighted the mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula, unaware that three days earlier the continent had already been discovered by the Russian Antarctic expedition of Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen and Mihail Lazarev.

One year later, the Russians had circumnavigated Antarctica and arrived in the South Shetlands region. On 6 February 1821 they approached Livingston Island and observed eight British and American ships off Byers Peninsula. While sailing between Deception and Livingston, Bellingshausen met with American sealer Nathaniel Palmer, yet another pioneer of Antarctic exploration who is alleged to have sighted the mainland himself during the previous November. Palmer informed the Russians that seal hunting in the area was going at full steam, with Smith alone having taken 60,000 seal skins.[29] The Antarctic sealing industry south of 60°S was initiated in the 1819/20 summer season by the early voyage of Joseph Herring (ship's mate during Smith's first visit) who stepped ashore in Hersilia Cove, Rugged Island on Christmas Day of 1819, followed by James Sheffield (with second mate, a 20-year-old Nathaniel Palmer), James Weddell, and possibly Carlos Timblón from Buenos Aires.

American historian Edouard Stackpole wrote of the early 19th century sealers:

While the indiscriminate slaughter of the seals in the South Shetlands was a sad feature of an otherwise thrilling story of maritime adventure, it is not the whole story. Despite their brutal trade, which made them realists in its fullest sense, the captains, officers and men were not all reckless, cynical and dissolute. True, they lived a hard life of necessity, but their fragmentary records reveal them as resourceful mariners, fully aware of their danger but willing to risk their lives in their hazardous calling.[32]

As the seals were killed onshore the hunters spent protracted periods of time there, seeking refuge from the elements in purpose-built stone huts, tent bivouacs or natural caves. Livingston Island became the most populous place in Antarctica for a time, its dwellers exceeding 200 in number during the 1820–23 South Shetlands sealing rush.[33][3] The principal sealer ‘settlements’ on the island were situated on Byers Peninsula, as well as at Cape Shirreff and Elephant Point.[34] Argentine archaeological research has identified 26 human-built shelter structures on Byers Peninsula alone.[35] There were some women among the early inhabitants of the island, as evidenced by a 1985 discovery of the grave of a 21-year-old woman of mixed European and Native American descent at Yamana Beach on Cape Shirreff, dated to the early 19th century.[36] Remains of huts and sealer artefacts are still found on Livingston, which possesses the second greatest concentration of historical sites in Antarctica (after South Georgia). The memory of that epoch survives, other than in archaeological finds, also in a dozen preserved ship logs and as many memoirs, such as the candid story published in 1844 by one Thomas Smith who sailed to Livingston in the sealer Hetty under Captain Ralph Bond during the 1820/21 season.[37]

Sealing was replaced by another rush of unsustainable commercial exploitation during the 20th century – Antarctic whaling. This time Livingston Island was not directly involved, although the southernmost Hektor Whaling Station was operated by Norway on nearby Deception Island from 1912 to 1931.[4] Whaling likewise depleted its resource and gave way at the turn of the 1970s to modern Antarctic fishing industry pioneered by the fishing fleets of the Soviet Union, Poland, East Germany and Bulgaria.[38]

A significant milestone in Livingston Island's history was the Antarctic Treaty signed in 1959 and entered into force in 1961, which effectively placed the region south of 60° south latitude under the joint governance of the consultative (voting) parties to the treaty, providing in particular for the freedom of scientific exploration. The treaty left the personnel of the Antarctic bases under their respective home countries’ jurisdiction, and essentially froze the existing sovereignty claims. (Livingston, in particular, was claimed by Britain in 1820 with letters patent of annexation promulgated in 1908, by Chile in 1940 and by Argentina in 1942 — claims not recognized, among others, by the US and Russia, which have formally reserved their rights to claim Antarctic territories.[39]) Since then, the evolving Antarctic Treaty System has been providing an increasingly comprehensive legal framework for all Antarctic-related activities, including environmental protection and exploitation of marine living resources, and has proved an example of uniquely successful international cooperation.

Toponymy

The names of many geographical features on the island refer to its early history. Among the commemorated are ship captains such as the Americans James Sheffield, Christopher Burdick, Charles Barnard, Chester, Robert Johnson, Donald MacKay, Robert Inott, David Leslie, Benjamin Brunow, Robert Macy, Prince Moores, William Napier and Daniel Clark (first mate), the Britons William Shirreff, M’Kean, John Walker, Ralph Bond, Christopher MacGregor, T. Binn and William Bowles, the Australian Richard Siddins, people like the New York shipowner James Byers, the American whaling merchants William and Francis Rotch, British Admiralty hydrographer Thomas Hurd, and John Miers, publisher of the first chart of the South Shetland Islands based on the work of William Smith, or sealing vessels like Huron, Williams (William Smith's brig), Hersilia, Samuel, Gleaner, Huntress, Charity, Hannah, Henry, John, Hero (Nathaniel Palmer's sloop), Cora, Hetty, Essex and Mercury.

Some of the place names given by the nineteenth century sealers are descriptive, such as Devils Point, Hell Gates and Neck or Nothing Passage, hazardous places where ships and people were lost; False Bay, sometimes confused in thick weather with neighbouring South Bay; Needle Peak; Black Point; or the Robbery Beaches where American sealers were robbed of their sealskins by the British. However, names like Livingston, Mount Friesland, Ereby Point and Renier Point that also became established during the first few seasons after the discovery of the island remain of unknown origin.

Livingston was the third name of the island, introduced in 1821 by the British sealer Robert Fildes (as quoted above), replacing the popular early name Friesland Island (variously spelled also as Frieseland, Freesland, Freeseland, Frezeland, Freezland, Frezland and Freezeland[40]) and the name Smolensk given by Bellingshausen in commemoration of one of the great battles of the Napoleonic Wars. The toponyms Friesland and Smolensk are now preserved as Mount Friesland and Smolensk Strait respectively. While the name Livingston is sometimes misspelt as Livingstone, it has nothing to do with the Scotsman David Livingstone, an 8-year-old boy in 1821 who was yet to become a cotton mill worker and still later a missionary and famous explorer of Africa.[7]

Some place names on the island are given by Argentina and Chile, such as Charrúa Ridge, Scesa Point, Arroyo Point, Bruix Cove, Ocoa Point, Dreyfus Point, Mansa Cove, Agüero Point etc. Several Argentine names commemorate crewmen of the Argentine Navy Lockheed Neptune aircraft that crashed in poor weather on the then uninhabited island on 15 September 1976, killing 10 aircrew and a civilian television cameraman.[41] Features like Point Smellie and Willan Nunatak are named after British scientists who have carried out field work on the island. Other names reflect the Spanish and Bulgarian exploration and mapping in the area, such as Española Cove, Mount Reina Sofía, San Telmo Island, Ballester Point and Castellvi Peak (after Antonio Ballester and Josefina Castellví, doyens of the Spanish Antarctic programme), Quiroga Ridge, Dañobeitia Crag, Ojeda Beach, Enrique Hill, Sàbat Hill, Casanovas Peak, Bulgarian Beach, Krum Rock (or Krumov Kamak), Pimpirev Beach (after Christo Pimpirev, doyen and leader of the Bulgarian Antarctic programme), Vergilov Ridge, Kuzman Knoll, Dimov Gate, Gurev Gap, Yankov Gap etc. Hespérides Point is named after BIO Hespérides, a Spanish Navy oceanographic vessel serving in particular as a resupply ship for the Spanish and Bulgarian bases for many years. Rongel Point and Las Palmas Cove are also named after modern Antarctic ships.

A concentration of place names (probably the highest in Antarctica) arising from local topographic diversity – over fifty names, mostly Chilean, occurs on the small 3.22 km2 (1.24 sq mi)[6] ice-free headland forming the northern extremity of Ioannes Paulus II Peninsula and ending in Cape Shirreff.

Scientific bases and camps

The first modern, 'post-sealer' habitation facility on Livingston Island was the British base camp Station P that operated during the 1957/58 summer season at South Bay, on the east side of the small ice-free promontory ending in Hannah Point.[3] The scientific bases of Juan Carlos I (Spain) and St. Kliment Ohridski (Bulgaria; often shortened by non-Bulgarians to Ohridski Base, sometimes misspelt as Ohridiski) were established in early 1988 at South Bay, on the northwest coast of Hurd Peninsula. Doctor Guillermo Mann Base (Chile) and adjoining Cape Shirreff Field Station (USA) operate on Cape Shirreff since 1991 and 1996 respectively, while Cámara Base (Argentina) on the tiny nearby Half Moon Island is one of the early bases in the Antarctic Peninsula region established in 1953. These facilities are used also by visiting scientists from various nations; in particular, the Bulgarian base has hosted the first steps in Antarctic research by scientists from countries such as Portugal, Luxembourg, North Macedonia, Mongolia and Turkey.

All four bases are permanent settlements, although inhabited only during the summer season. Their accommodation capacity is ca. 51, 18, 11 and 12 persons respectively, making it a total of 92 persons (80 for Livingston Island proper). The number of people inhabiting the bases in any particular season is actually greater as some of them stay for part of the time and are replaced by others.[3][42]

Occasional or more permanent field camps support research in remote areas of the island. Camp Byers (Spain) operates regularly on the banks of Petreles Stream, South Beaches near Nikopol Point on Byers Peninsula; that site is also designated for use as an International Field Camp. The seasonal Camp Livingston (Argentina) is also situated on Byers Peninsula, while Sally Rocks Camp (Bulgaria) supported geological research on southern Hurd Peninsula. Camp Academia site situated at elevation 541 m (1,775 ft) in upper Huron Glacier, Wörner Gap area served as a base camp of the Tangra 2004/05 topographic survey. It is accessible by 11–12.5 km (6.8–7.8 mi) routes from St. Kliment Ohridski and Juan Carlos I base respectively, and offers convenient overland access to Tangra Mountains to the south; Bowles Ridge, Vidin Heights, Kaliakra Glacier and Saedinenie Snowfield areas to the north; Huron Glacier to the east; and Perunika Glacier and Huntress Glacier to the west. The site is named for the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in appreciation of its contribution to Antarctic exploration, and has been designated as the summer post office Tangra 1091 of the Bulgarian Posts since 2004. Field work done out of Camp Academia during the 2004/05 season was noted in 2012 by Discovery Channel, the Natural History Museum, the Royal Collection and the British Antarctic Survey as a timeline event in Antarctic exploration.[43][44]

Protected areas and sites

In order to protect Antarctica, the Antarctic Treaty system enforces a strict general regime regulating human presence and activities on the continent, and designates certain protected territories where access is allowed only for scientific purposes, and with special permission.

There are two such nature reserves on Livingston Island established in 1966: Antarctic Specially Protected Areas ASPA 149 Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Island, and ASPA 126 Byers Peninsula. These comprise respectively Byers Peninsula, which is the largest ice-free land area in the South Shetlands, and the small peninsula of Cape Shirreff together with Gerlovo Beach, nearby San Telmo Island and adjacent waters.

Subject of protection in ASPA 126 are the fossils demonstrating the link between Antarctica and other austral continents, a variety of abundant flora and fauna including colonies of seals and penguins that are the subject of scientific study and monitoring, as well as numerous historical monuments dating from the nineteenth century.[45] This territory has been identified also as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of its breeding colonies of Antarctic terns and kelp gulls.[46] ASPA 149 features diverse plant and animal life, notably penguin and seal colonies including the largest fur seal breeding colony in the Antarctic Peninsula region.[47] No longer hunted, fur seals have successfully re-colonized their original habitats on Livingston Island and elsewhere in the Antarctic Peninsula region.

The land boundary of ASPA 126 Byers Peninsula was shifted eastwards to 60º53'45"W in 2016 to include along with Byers Peninsula also all ice-free ground and ice sheet west of Clark Nunatak and Rowe Point, increasing the overall surface area of that protected territory to 84.7 km2 (32.7 sq mi). Two restricted zones of scientific importance to Antarctic microbiology have been further designated within these boundaries with greater restriction placed on access with the aim of preventing microbial or other contamination by human activity: Ray Promontory in the west, and Ivanov Beach and northwestern Rotch Dome in the east.[45]

There are two Historic Sites or Monuments of Antarctica on the island: San Telmo Cairn (HSM 59) at Cape Shirreff, which commemorates the 644 Spaniards lost on board the San Telmo in 1819, and the Lame Dog Hut (HSM 91) at St. Kliment Ohridski base, which is the oldest preserved building on Livingston Island and together with its associated artefacts is considered a part of the cultural and historic heritage of the island and Antarctica. The hut hosts the Livingston Island Museum, a branch of the National Museum of History in Sofia.[48]

Tourism

Antarctic shipborne tourism was initiated in the 1957/58 season with four cruises operated by Chile and Argentina in the South Shetland Islands.[49] Since then the number of tourists visiting Antarctica has grown to several tens of thousands annually. Over 95% of them tour the South Shetlands and the nearby Antarctic Peninsula. Hannah Point on the south coast of Livingston, Half Moon Island off its east coast, Aitcho Islands just north of Greenwich Island, and Deception Island are among the most popular destinations. Tourists arrive mainly in cruise ships, and are landed by Zodiac rigid inflatable boats to walk along designated trails led by tourist guides and enjoy picturesque scenery and wildlife. Zodiac boats are the preferred means of local sea transport, being particularly suitable for navigation among floating ice and landing at places lacking port facilities. Naturally, this is only possible in summer as the sea surface is partially or completely frozen in ice over one meter thick in winter.[3] Visits by yachts and extreme tourism such as kayaking have become increasingly popular, too.

_30.jpg)

Cruise ships visiting Hannah Point occasionally make a 12 km (7 mi) sightseeing detour to the Bulgarian base, where the tourists could visit the Livingston Island Museum established in October 2012, the old and new chapels of St. Ivan Rilski – the first Eastern Orthodox edifice in Antarctica consecrated in February 2003, and the Monument to the Cyrillic Script erected on Pesyakov Hill in March 2018.[50] Livingston Island has some particular relationship with the Cyrillic alphabet as the modern system for the Romanization of Bulgarian was developed in 1995 for use in Bulgarian-related place names on the island by the Antarctic Place-names Commission,[51] and later became official for Bulgaria, UK, USA and UN.[52][53]

The northeasternmost slopes of Tangra Mountains between Elena Peak and Renier Point together with the adjacent portion of Sopot Ice Piedmont are a popular site for backcountry skiing and climbing, with skiers landed by Zodiac boats from cruise ships visiting Half Moon Island's vicinity.[54][55]

Honours

Several squares and streets in Bulgarian towns and cities are named after Livingston Island, such as Livingston Island Square in Samuil and Kula, and Livingston Island Street in Gotse Delchev, Yambol, Petrich, Sofia, Lovech and Vidin.[56][57][58][59][60]

Gallery

.jpg)

%E2%80%93Southern_elephant_seal_(Mirounga_leonina)_01.jpg)

Antarctic pearlwort, one of the two native flowering plants

Antarctic pearlwort, one of the two native flowering plants.jpg)

- Volcanic ash layers in Perunika Glacier

On a survey mission

On a survey mission Wedding in Livingston Island's waters

Wedding in Livingston Island's waters Livingston Island's Christmas tree

Livingston Island's Christmas tree Spanish refuge at Mount Reina Sofía

Spanish refuge at Mount Reina Sofía The old Spanish base

The old Spanish base

The old St. Ivan Rilski Chapel

The old St. Ivan Rilski Chapel Tangra Mountains from Chilean and US base vicinity

Tangra Mountains from Chilean and US base vicinity

See also

- Antarctic Place-names Commission

- Bulgarian toponyms in Antarctica

- Camp Academia

- Camp Byers

- Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica – The authoritative international gazetteer containing all the Antarctic toponyms

- Juan Carlos I Antarctic Base

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

- Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR)

- South Shetland Islands – A group of islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula

- St. Kliment Ohridski Base

- Tangra Mountains

- Tangra 2004/05 Survey – Bulgarian geographical expedition to Antarctica

- Territorial claims in Antarctica – Wikimedia list article

Maps

- Chart of South Shetland including Coronation Island, &c. from the exploration of the sloop Dove in the years 1821 and 1822 by George Powell Commander of the same. Scale ca. 1:200000. London: Laurie, 1822

- South Shetland Islands. Scale 1:200000 topographic map. DOS 610 Sheet W 62 60. Tolworth, UK, 1968

- South Shetland Islands. Scale 1:200000 topographic map. DOS 610 Sheet W 62 58. Tolworth, UK, 1968

- Livingston Island to King George Island. Scale 1:200000. Admiralty Chart 1776. UK Hydrographic Office, 1968

- Isla Elefante a Isla Trinidad. Mapa hidrográfico a escala 1:500000 / 1:350000. Valparaíso: Instituto Hidrográfico de la Armada de Chile, 1971

- Islas Shetland del Sur de Isla 25 de Mayo a Isla Livingston. Mapa hidrográfico a escala 1:200000. Buenos Aires: Servicio de Hidrografía Naval de la Armada, 1980

- Islas Livingston y Decepción. Mapa topográfico a escala 1:100000. Madrid: Servicio Geográfico del Ejército, 1991

- Isla Livingston: Península Hurd. Mapa topográfico de escala 1:25000. Madrid: Servicio Geográfico del Ejército, 1991. (Map reproduced on p. 16 of the linked work)

- Península Byers, Isla Livingston. Mapa topográfico a escala 1:25000. Madrid: Servicio Geográfico del Ejército, 1992. (Map image on p. 55 of the linked study)

- L. Ivanov. St. Kliment Ohridski Base, Livingston Island. Scale 1:1000 topographic map. Sofia: Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria, 1996. (First Bulgarian Antarctic topographic map; original version)

- L. Ivanov. Livingston Island: Central-Eastern Region. Scale 1:25000 topographic map. Sofia: Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria, 1996

- S. Soccol, D. Gildea and J. Bath. Livingston Island, Antarctica. Scale 1:100000 satellite map. The Omega Foundation, USA, 2004

- L. Ivanov et al. Antarctica: Livingston Island and Greenwich Island, South Shetland Islands (from English Strait to Morton Strait, with illustrations and ice-cover distribution). Scale 1:100000 topographic map. Sofia: Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria, 2005

- L. Ivanov. Antarctica: Livingston Island and Greenwich, Robert, Snow and Smith Islands. Scale 1:120000 topographic map. Troyan: Manfred Wörner Foundation, 2010. ISBN 978-954-92032-9-5 (First edition 2009. ISBN 978-954-92032-6-4)

- Antarctica, South Shetland Islands, Livingston Island: Bulgarian Antarctic Base. Sheets 1 and 2. Scale 1:2000 topographic map. Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre Agency, 2016. (in Bulgarian, map images on slides 6 and 7 of the linked report)

- L. Ivanov. Antarctica: Livingston Island and Smith Island. Scale 1:100000 topographic map. Manfred Wörner Foundation, 2017. ISBN 978-619-90008-3-0

- Antarctic Digital Database (ADD). Scale 1:250000 topographic map of Antarctica. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). Since 1993, regularly upgraded and updated

In popular culture

The Killing Ship by Simon Beaufort

- The area of the Spanish and Bulgarian bases on Livingston Island is the setting of the book Las aventuras de Piti en la Antártida by the Spanish author and polar explorer Javier Cacho.[61]

- The British romantic novelist Rosie Thomas (pseudonym of Janey King) wrote her book Sun at Midnight at the Bulgarian base during the 2002/03 austral summer.[62][63]

- The island contributes to the mise-en-scène of the 2016 Antarctica thriller novel The Killing Ship by Simon Beaufort (joint alias of Elizabeth Cruwys and Beau Riffenburgh), with action spreading from Hannah Point to Byers Peninsula via Ivanov Beach, skirting Verila Glacier and Rotch Dome in the process.[64][65]

- The naming of St. Boris Peak after a Bulgarian saint was reminded by the British press in connection with the victory of Boris Johnson in the London mayoral election on 2 May 2008, that particular day being St. Boris's Day in the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.[66]

- The cover of the VA album Under Heaven: Vinson Massif (2010) actually features not a photo of Vinson Massif but one of Livingston's Elena, Yavorov and Delchev Peaks instead.[67] Both the picture and the misidentification may have possibly originated in the ‘Vinson Massif’ entry of the ‘Seven Summits Quest’ website.[68]

Notes

- One-Sixth of the World – Putin Hands Out Special Assignment to Recover Old Names of Russian Lands. Vesti News, 29 April 2018

- Livingston Island. British Antarctic Territory Gazetteer. UK Antarctic Place-names Committee (Narrative fragment: “Ostrov Smolensk, so called by RAE after the Battle of Smolensk in 1812 (Bellingshausen, 1831a, sheet 62)”)

- L. Ivanov. General Geography and History of Livingston Island. In: Bulgarian Antarctic Research: A Synthesis. Eds. C. Pimpirev and N. Chipev. Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski University Press, 2015. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-954-07-3939-7

- Deception Island: Management Package. Measure 10 (2012) Annex. ATCM XXXV Final Report. Hobart, Australia, 2012

- S. Kraus, A. Kurbatov and M. Yates. Geochemical signatures of tephras from Quaternary Antarctic Peninsula volcanoes. Andean Geology 40 (2013) 1. pp. 1–40

- L. Ivanov. Antarctica: Livingston Island and Greenwich, Robert, Snow and Smith Islands. Scale 1:120000 topographic map. Troyan: Manfred Wörner Foundation, 2010. ISBN 978-954-92032-9-5 (First edition 2009. ISBN 978-954-92032-6-4)

- L. Ivanov and N. Ivanova. Livingston Island. In: Antarctic: Nature, History, Utilization, Geographic Names and Bulgarian Participation. Sofia: Manfred Wörner Foundation, 2014. pp. 16–20; p. 70. (in Bulgarian) ISBN 978-619-90008-1-6 (Second revised and updated edition Archived 2016-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, 2014. 411 pp. ISBN 978-619-90008-2-3)

- J. López Martínez. Geología de la Antártida Occidental. Simposios T3. Salamanca: III Congreso Geológico de España y VIII Congreso Latinoamericano de Geología, 1992. pp. 271–282

- E. Serrano and J. López Martínez. Rock glaciers in the South Shetland Islands, Western Antarctica. Geomorphology 35 (2000) 1. pp. 145–162

- M. Toro, A. Camacho, C. Rochera, E. Rico, M. Bañón, E. Fernández-Valiente, E. Marco, A. Justel, M. Avendaño, Y. Ariosa, W. Vincent and A. Quesada. Limnological characteristics of the freshwater ecosystems of Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island in maritime Antarctica. Polar Biology 30 (2007). pp. 635–649

- AUSPOS Online GPS Processing Report: Job number #101306. Space Geodesy Analysis Centre, The National Mapping Division. Geoscience Australia, 22 December 2003. 5 pp.

- D. Gildea. Antarctica, Antarctic Peninsula, Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, Second Ascent of Mt. Friesland and New Altitude. The American Alpine Journal 46 (2004) 78. pp. 329–331

- D. Boyanov and N. Petkov. The Peaks of Tangra Mountains: Project Report Part Two 2016/17. Sofia, February 2017 (in Bulgarian)

- I.M. Howat, C. Porter, B.E. Smith, M.-J. Noh and P. Morin. The Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica. The Cryosphere 13, 2019. pp. 665–674 (Antarctic REMA Exlorer)

- D. Gildea. Mountaineering in Antarctica: complete guide: Travel guide. Primento and Editions Nevicata, 2015. 192 pp. ISBN 978-2-51103-136-0

- Antarctica: Livingston Island. Climb Magazine, Issue 14. Kettering, UK, April 2006. pp. 89–91

- L. Ivanov. Livingston Island: Tangra Mountains, Komini Peak, west slope new rock route; Lyaskovets Peak, first ascent; Zograf Peak, first ascent; Vidin Heights, Melnik Peak, Melnik Ridge, first ascent. The American Alpine Journal, 2005. pp. 312–315

- N. Petkov. Livingston Island, Falsa Aguja and Sofia Peak. American Alpine Journal: Climbs And Expeditions, 2016. (Full expedition report Archived 2019-04-08 at the Wayback Machine by N. Petkov and D. Boyanov)

- J. Purdy. Laurie’s Sailing Directory of the Ethiopic or Southern Atlantic Ocean; Including the Coasts of Brasil etc. to the Rio de la Plata, the Coast thence to Cape Horn, and the African Coast to the Cape of Good Hope etc; Including the Islands between the Two Coasts. 4th ed. London: Richard Laurie, 1855. p. 173 (Excerpts from reports by early explorers of the South Shetlands, pp. 166–173)

- N. Chipev and K. Veltchev. Livingston Island: an Environment for Antarctic Life. In: Bulgarian Antarctic Research: Life Sciences. Vol. 1. Eds. S. Golovatch and L. Penev. Sofia: Pensoft Publishers, 1996. pp. 1–6

- D. Gildea. Omega Livingston Island GPS Expedition 2003. Dispatches, 17 December 2003

- Antarctic Sun, March 6, 2009

- C. Recio, F. Navarro, J. Otero, J. Lapazaran and S. Gonzàlez. Effects of recent cooling in the Antarctic Peninsula on snow density and surface mass balance. Polish Polar Research 39 (2018) 4. pp. 457–480

- L. Ivanov. SCAR SCAGI National Report 2017 Bulgaria. Bremerhaven, 12–13 June 2017. (Mapping on slide 9 of the linked report)

- A. Labajo. Updated Information on Spain’s Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic “Weather-Forecasting” Interests. For The International Antarctic Weather Forecasting Handbook: IPY 2007–08 Supplement, 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- C. Darwin. Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. 2nd ed. London: John Murray, 1845. p. 249

- L. Sancho, F. Schulz, B. Schroeter and L. Kappen. Bryophyte and lichen flora of South Bay (Livingston Island: South Shetland Islands, Antarctica). Nova Hedwigia 68 (1999) No. 3–4. pp. 301–337

- R. Headland. A Chronology of Antarctic Exploration: A Synopsis of Events and Activities From the Earliest Times Until the International Polar Years, 2007–09. London: Bernard Quaritch, 2009. 722 pp. (1989 first edition)

- Ф. Беллингсгаузен. Двукратные изыскания в Южном Ледовитом Океане, и плавание вокруг света, в продолжение 1819, 1820 и 1821 годов. Две части. С атласом в 64 л. Санкт-Петербург. В типографии Глазунова, 1831. Ч. I 397 с., ч. II 326 с.

- L. Mollá. El navío San Telmo: Una historia sin final. Puerto de Santa María, abril de 2000

- Manuel Martín-Bueno. Catedrático de Arqueología. University of Zaragoza Arqueología Antártica:El Proyecto San Telmo y el descubrimiento de Terra Australis Antarctica.

- E. Stackpole. The American Sealers and the Discovery of the Continent of Antarctica: The voyage of the Huron and the Huntress. Mystic, Connecticut, 1955. 86 pp.

- B. Basberg and R. Headland. The 19th Century Antarctic Sealing Industry: Sources, Data and Economic Significance. SCAR Open Science Conference. St. Petersburg, 2008. 24 pp.

- R. Lewis Smith and H. Simpson. Early Nineteenth century sealers' refuges on Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands. British Antarctic Survey Bulletin 74 (1987). pp. 49–72

- A. Zarankin and M. Senatore. Archaeology in Antarctica: Nineteenth-Century Capitalism Expansion Strategies. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 9 (2005) 1. pp. 43–56

- D. Torres. Observations on ca. 175-year old human remains from Antarctica (Cape Shirreff, Livingston Island, South Shetlands). International Journal of Circumpolar Health 58 (1999) 2. pp. 72–83

- T. Smith. A Narrative of the Life, Travels, and Sufferings of Thomas W. Smith etc. Boston: W.C. Hill, 1844. pp. 159–163

- K.-H. Kock. Antarctic Fish and Fisheries. Cambridge University Press, 1992. 359 pp.

- R. Wilson. National Interests and Claims in the Antarctic. Arctic 17 (1964) No. 1. pp. 1–64

- Livingston Island. UK Antarctic Place-names Committee. BAT Gazetteer, row 4451

- Lockheed SP-2H Neptune – Matr. 2-P-103 – Shetland del Sur. Arqueologia Aeronautica, 7 de octubre de 2015

- Pedro Duque inaugura la remodelación de una base en la Antártida. Archived 2019-04-04 at the Wayback Machine EFE Future website, 4 February 2019

- Discovering Antarctica Overview. Discovery Channel UK website, 2012

- 14 November 2004: Tangra. Discovering Antarctica Timeline. Discovery Channel UK website, 2012

- Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 126 Byers Peninsula. Measure 4 (2016), ATCM XXXIX Final Report. Santiago, 2016

- Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island. BirdLife data zone: Important Bird Areas. BirdLife International, 2019

- Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 149 Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Island. Measure 2 (2005), Annex H, ATCM XXVIII Final Report. Stockholm, 2005

- Certificate of the Livingston Island Museum. Sofia: National Museum of History, October 2012 (in Bulgarian)

- National Research Council. Appendix A: Tourism. Science and Stewardship in the Antarctic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 1993. 124 pp. ISBN 978-0-309-04947-4

- B. Lazarov. The Three Monuments of the Cyrillic Alphabet. EUSCOOP News from Bulgaria, 13 March 2018

- L. Ivanov. Toponymic Guidelines for Antarctica. Sofia: Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria, 1995

- Romanization System In Bulgaria. Tenth United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names. New York, 2012

- Romanization of Bulgarian: BGN/PCGN 2013 Agreement

- S. Romeo. IceAxe.TV Antarctic Peninsula Ski Cruise Update 4. TetonAT website, 2009

- T. Crocker. Livingston Island, South Shetlands. Liftlines Skiing and Snowboarding Forums, 17 November 2011

- Vidin Info (in Bulgarian)

- Gotse Delchev Municipality site (in Bulgarian)

- Razgrad News (in Bulgarian)

- Lovech City Council site (in Bulgarian)

- Gradski Vestnik (in Bulgarian)

- J. Cacho. Las aventuras de Piti en la Antártida. Madrid: Ediciones Tao, 2001. 215 p. ISBN 978-84921-2806-8 (Bulgarian edition in 2008)

- R. Thomas. Sun at Midnight. HarperCollins, 2005. 496 pp. ISBN 978-0-00-717352-5

- Q&A with Rosie Thomas. Connect with Chicklit Club, July 2017

- S. Beaufort. The Killing Ship. Sutton, Surrey: Severn House Publishers, 2016. 224 pp. ISBN 978-0-7278-8639-2

- The Killing Ship. Susanna Gregory Website, 2019

- M. Kennedy. St Boris's big day. The Guardian, 3 May 2008

- Under Heaven: Vinson Massif. Album, August 2010

- Vinson Massif. The Seven Summits Quest, June 2008

Bibliography

- C. Pimpirev and N. Chipev, eds. Bulgarian Antarctic Research: A Synthesis. Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski University Press, 2015. 334 pp. ISBN 978-954-07-3939-7 (Concise presentation of the Bulgarian Antarctic research in the field of earth and life sciences carried out on Livingston Island during the period 1988 – 2015)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Livingston Island. |

- Base Doctor Guillermo Mann (Chile)

- Bulgarian Antarctic Base St. Kliment Ohridski

- Expedition Omega Livingston 2003. The Omega Foundation, USA, 2003

- Expedition Tangra 2004/05

- Juan Carlos I Spanish Antarctic Station

- Livingston Island. Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria, 2006

- South Shetland Islands. 70south, 2005. Information on the South Shetlands including Livingston Island

![]()

.jpg)

.svg.png)