Robert Falcon Scott

Robert Falcon Scott CVO (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition of 1910–1913. On the first expedition, he set a new southern record by marching to latitude 82°S and discovered the Antarctic Plateau, on which the South Pole is located. On the second venture, Scott led a party of five which reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, less than five weeks after Amundsen's South Pole expedition.

Robert Falcon Scott | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Robert Falcon Scott in 1905 | |

| Born | 6 June 1868 Plymouth, Devon, England |

| Died | c. 29 March 1912 (aged 43) Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1881–1912 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Expeditions | |

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Sir Peter Scott |

A planned meeting with supporting dog teams from the base camp failed, despite Scott's written instructions, and at a distance of 162 miles (261 km) from their base camp at Hut Point and approximately 12.5 miles (20 km) from the next depot, Scott and his companions died. When Scott and his party's bodies were discovered, they had in their possession the first Antarctic fossils ever discovered.[1] The fossils were determined to be from the Glossopteris tree and proved that Antarctica was once forested and joined to other continents.[2]

Before his appointment to lead the Discovery expedition, Scott had followed the career of a naval officer in the Royal Navy. In 1899, he had a chance encounter with Sir Clements Markham, the president of the Royal Geographical Society, and thus learned of a planned Antarctic expedition, which he soon volunteered to lead.[3] Having taken this step, his name became inseparably associated with the Antarctic, the field of work to which he remained committed during the final 12 years of his life.

Following the news of his death, Scott became a celebrated hero, a status reflected by memorials erected across the UK. However, in the last decades of the 20th century, questions were raised about his competence and character. Commentators in the 21st century have regarded Scott more positively after assessing the temperature drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) in March 1912, and after re-discovering Scott's written orders of October 1911, in which he had instructed the dog teams to meet and assist him on the return trip.[4]

Early life

Family

Scott was born on 6 June 1868, the third of six children and elder son of John Edward, a brewer and magistrate, and Hannah (née Cuming) Scott of Stoke Damerel, near Devonport. There were also naval and military traditions in the family, Scott's grandfather and four uncles all having served in the army or navy.[5] John Scott's prosperity came from the ownership of a small Plymouth brewery which he had inherited from his father and subsequently sold.[6] Scott's early childhood years were spent in comfort, but some years later, when he was establishing his naval career, the family suffered serious financial misfortune.[7]

In accordance with the family's tradition, Scott and his younger brother Archie were predestined for careers in the armed services. Scott spent four years at a local day school before being sent to Stubbington House School in Hampshire, a cramming establishment that prepared candidates for the entrance examinations to the naval training ship HMS Britannia at Dartmouth. Having passed these exams Scott began his naval career in 1881, as a 13-year-old cadet.[8]

Early naval career

In July 1883, Scott passed out of Britannia as a midshipman, seventh overall in a class of 26.[9] By October, he was en route to South Africa to join HMS Boadicea, the flagship of the Cape squadron, the first of several ships on which he served during his midshipman years. While stationed in St Kitts, West Indies, on HMS Rover, he had his first encounter with Clements Markham, then Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, who would loom large in Scott's later career. On this occasion, 1 March 1887, Markham observed Midshipman Scott's cutter winning that morning's race across the bay. Markham's habit was to "collect" likely young naval officers with a view to their undertaking polar exploration work in the future. He was impressed by Scott's intelligence, enthusiasm and charm, and the 18-year-old midshipman was duly noted.[3]

In March 1888 Scott passed his examinations for sub-lieutenant, with four first class certificates out of five.[10] His career progressed smoothly, with service on various ships and promotion to lieutenant in 1889. In 1891, after a long spell in foreign waters, he applied for the two-year torpedo training course on HMS Vernon, an important career step. He graduated with first class certificates in both the theory and practical examinations. A small blot occurred in the summer of 1893 when, while commanding a torpedo boat, Scott ran it aground, a mishap which earned him a mild rebuke.[11]

During the research for his dual biography of Scott and Roald Amundsen, polar historian Roland Huntford investigated a possible scandal in Scott's early naval career, related to the period 1889–1890 when Scott was a lieutenant on HMS Amphion. According to Huntford, Scott "disappears from naval records" for eight months, from mid-August 1889 until 26 March 1890. Huntford hints at involvement with a married American woman, a cover-up, and protection by senior officers. Biographer David Crane reduces the missing period to eleven weeks, but is unable to clarify further. He rejects the notion of protection by senior officers on the grounds that Scott was not important or well-connected enough to warrant this. Documents that may have offered explanations are missing from Admiralty records.[12][13]

In 1894, while serving as torpedo officer on the depot ship HMS Vulcan, Scott learned of the financial calamity that had overtaken his family. John Scott, having sold the brewery and invested the proceeds unwisely, had lost all his capital and was now virtually bankrupt.[14] At the age of 63, and in poor health, he was forced to take a job as a brewery manager and move his family to Shepton Mallet, Somerset. Three years later, while Robert was serving with the Channel squadron flagship HMS Majestic, John Scott died of heart disease, creating a fresh family crisis.[15] Hannah Scott and her two unmarried daughters now relied entirely on the service pay of Scott and the salary of younger brother Archie, who had left the army for a higher-paid post in the colonial service. Archie's own death in the autumn of 1898, after contracting typhoid fever, meant that the whole financial responsibility for the family rested on Scott.[16]

Promotion, and the extra income this would bring, now became a matter of considerable concern to Scott.[17] In the Royal Navy however, opportunities for career advancement were both limited and keenly sought after by ambitious officers. Early in June 1899, while home on leave, he had a chance encounter in a London street with Clements Markham, who was now knighted and President of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), and learned for the first time of an impending Antarctic expedition with Discovery, under the auspices of the RGS. It was the opportunity for early command and a chance to distinguish himself, rather than any predilection for polar exploration which motivated Scott, according to Crane.[18] What passed between them on this occasion is not recorded, but a few days later, on 11 June, Scott appeared at the Markham residence and volunteered to lead the expedition.[3]

Discovery expedition, 1901–1904

The British National Antarctic Expedition, later known as the Discovery Expedition, was a joint enterprise of the RGS and the Royal Society. A long-cherished dream of Markham's, it required all of his skills and cunning to bring the expedition to fruition, under naval command and largely staffed by naval personnel. Scott may not have been Markham's first choice as leader but, having decided on him, the older man remained a constant supporter.[19] There were committee battles over the scope of Scott's responsibilities, with the Royal Society pressing to put a scientist in charge of the expedition's programme while Scott merely commanded the ship. Eventually, however, Markham's view prevailed;[20] Scott was given overall command, and was promoted to the rank of commander before Discovery sailed for the Antarctic on 6 August 1901.[21] King Edward VII, who showed a keen interest in the expedition, visited the Discovery the day before the ship left British shores in August 1901,[22] and during the visit appointed Scott a Member of the Royal Victorian Order, his personal gift.[23]

Experience of Antarctic or Arctic waters was almost entirely lacking within the 50-strong party and there was very little special training in equipment or techniques before the ship set sail.[24] Dogs were taken, as were skis, but the dogs succumbed to disease in the first season. Nevertheless, the dogs' performance impressed Scott, and, despite moral qualms, he implemented the principle of slaughtering dogs for dog-food to increase their range.[25] During an early attempt at ice travel, a blizzard trapped expedition members in their tent and their decision to leave it resulted in the death of George Vince, who slipped over a precipice on 11 March 1902.[26][27]

The expedition had both scientific and exploration objectives; the latter included a long journey south, in the direction of the South Pole. This march, undertaken by Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Edward Wilson, took them to a latitude of 82°17′S, about 530 miles (853 km) from the pole. A harrowing return journey brought about Shackleton's physical collapse and his early departure from the expedition.[28] The second year showed improvements in technique and achievement, culminating in Scott's western journey which led to the discovery of the Polar Plateau. This has been described by one writer as "one of the great polar journeys".[29] The scientific results of the expedition included important biological, zoological and geological findings.[30] Some of the meteorological and magnetic readings, however, were later criticised as amateurish and inaccurate.[31][32]

At the end of the expedition it took the combined efforts of two relief ships and the use of explosives to free Discovery from the ice.[33] Scott's insistence during the expedition on Royal Navy formalities had made for uneasy relations with the merchant navy contingent, many of whom departed for home with the first relief ship in March 1903. Second-in-command Albert Armitage, a merchant officer, was offered the chance to go home on compassionate grounds, but interpreted the offer as a personal slight, and refused.[34] Armitage also promoted the idea that the decision to send Shackleton home on the relief ship arose from Scott's animosity rather than Shackleton's physical breakdown.[35] Although there was later tension between Scott and Shackleton, when their polar ambitions directly clashed, mutual civilities were preserved in public;[36] Scott joined in the official receptions that greeted Shackleton on his return in 1909 after the Nimrod Expedition,[37] and the two exchanged polite letters about their respective ambitions in 1909–1910.[38]

Between expeditions

Popular hero

Discovery returned to Britain in September 1904. The expedition had caught the public imagination, and Scott became a popular hero. He was awarded a cluster of honours and medals, including many from overseas, and was promoted to the rank of captain.[39] He was invited to Balmoral Castle, where King Edward VII promoted him a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order.[40]

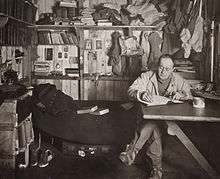

Scott's next few years were crowded. For more than a year he was occupied with public receptions, lectures and the writing of the expedition record, The Voyage of the Discovery. In January 1906, he resumed his full-time naval career, first as an Assistant Director of Naval Intelligence at the Admiralty and, in August, as flag-captain to Rear-Admiral Sir George Egerton on HMS Victorious.[41] He was now moving in ever more exalted social circles – a telegram to Markham in February 1907 refers to meetings with Queen Amélie of Orléans and Luis Filipe, Prince Royal of Portugal, and a later letter home reports lunching with the Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet and Prince Heinrich of Prussia. The telegram related to a collision involving Scott's ship, HMS Albemarle. Scott was cleared of blame.[42] HMS Albemarle, a battleship commanded by Scott, collided with the battleship HMS Commonwealth on 11 February 1907, suffering minor bow damage.[43]

Dispute with Shackleton

By early 1906, Scott queried the RGS about the possible funding of a future Antarctic expedition.[44] It was therefore unwelcome news to him that Ernest Shackleton had announced his own plans to travel to Discovery's old McMurdo Sound base and launch a bid for the South Pole from there.[45] Scott claimed, in the first of a series of letters to Shackleton, that the area around McMurdo was his own "field of work" to which he had prior rights until he chose to give them up, and that Shackleton should therefore work from an entirely different area.[45] In this, he was strongly supported by Discovery's former zoologist, Edward Wilson, who asserted that Scott's rights extended to the entire Ross Sea sector.[46] This Shackleton refused to concede.

According to a letter written to Standfords bookshop owner Edward Standford, Scott seemed to take offense with a map that was published that had shown how far south Scott and Shackleton traveled during the Discovery Expedition. Scott implied in this letter, dated in 1907 and discovered in the shop archives in 2018, that having the two men's names together on this map indicated that there was "dual leadership" between Scott and Shackleton which was "not in accordance with fact."[47] After the owner replied back with an apology to the issue, Scott expressed his regret at the nature of the previous letter and stated, "I tried to be impartial in giving credit to my companions who one and all laboured honestly and well as I have endeavoured to record....I understand now of course that you had no personal knowledge of the wording and I must express regret that I failed to realise your identity when I first wrote."[48]

Finally, to end the impasse, Shackleton agreed, in a letter to Scott dated 17 May 1907, to work to the east of the 170°W meridian and therefore to avoid all the familiar Discovery ground.[49] In the end it was a promise that he was unable to keep after his search for alternative landing grounds proved fruitless. With his only other option being to return home, he set up his headquarters at Cape Royds, close to the old Discovery base.[50] For this he was roundly condemned by the British polar establishment at the time.

Among modern polar writers, Ranulph Fiennes regards Shackleton's actions as a technical breach of honour, but adds: "My personal belief is that Shackleton was basically honest but circumstances forced his McMurdo landing, much to his distress."[51] The polar historian Beau Riffenburgh states that the promise to Scott "should never ethically have been demanded," and compares Scott's intransigence on this matter unfavourably with the generous attitudes of the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who gave freely of his advice and expertise to all, whether they were potential rivals or not. [52]

Marriage

Scott, who because of his Discovery fame had entered Edwardian society, first met Kathleen Bruce early in 1907 at a private luncheon party.[53] She was a sculptor, socialite and cosmopolitan who had studied under Auguste Rodin[54] and whose circle included Isadora Duncan, Pablo Picasso and Aleister Crowley.[55] Her initial meeting with Scott was brief, but when they met again later that year, the mutual attraction was obvious. A stormy courtship followed; Scott was not her only suitor—his main rival was would-be novelist Gilbert Cannan—and his absences at sea did not assist his cause.[56] However, Scott's persistence was rewarded and, on 2 September 1908, at the Chapel Royal, Hampton Court Palace, the wedding took place.[57] Their only child, Peter Markham Scott, born 14 September 1909,[58] was to found the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Terra Nova expedition, 1910–1912

Preparation

-en.svg.png)

Shackleton returned from the Antarctic having narrowly failed to reach the Pole, and this gave Scott the impetus to proceed with plans for his second Antarctic expedition.[59] On 24 March 1909, he took the Admiralty-based appointment of naval assistant to the Second Sea Lord which placed him conveniently in London. In December, he was released on half-pay, to take up the full-time command of the British Antarctic Expedition 1910, to be known as the Terra Nova expedition from its ship, Terra Nova.[60]

It was the expressed hope of the RGS that this expedition would be "scientific primarily, with exploration and the Pole as secondary objects"[61] but, unlike the Discovery expedition, neither they nor the Royal Society were in charge this time. In his expedition prospectus, Scott stated that its main objective was "to reach the South Pole, and to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement".[61] Scott had, as Markham observed, been "bitten by the Pole mania".[61]

In a memorandum of 1908, Scott presented his view that man-hauling to the South Pole was impossible and that motor traction was needed.[62] Snow vehicles did not yet exist however, and so his engineer Reginald Skelton developed the idea of a caterpillar track for snow surfaces.[63] In the middle of 1909 Scott realised that motors were unlikely to get him all the way to the Pole, and decided additionally to take horses (based on Shackleton's near success in attaining the Pole, using ponies),[64][65] and dogs and skis after consultation with Nansen during trials of the motors in Norway in March 1910.[66] Man-hauling would still be needed on the Polar Plateau, on the assumption that motors and animals could not ascend the crevassed Beardmore Glacier.

Dog expert Cecil Meares was going to Siberia to select the dogs, and Scott ordered that, while he was there, he should deal with the purchase of Manchurian ponies. Meares was not an experienced horse-dealer, and the ponies he chose proved mostly of poor quality, and ill-suited to prolonged Antarctic work.[38] Meanwhile, Scott also recruited Bernard Day, from Shackleton's expedition, as his motor expert.[67]

First season

On 15 June 1910, Scott's ship, Terra Nova, an old converted whaler, set sail from Cardiff, South Wales. Scott meanwhile was fundraising in Britain and joined the ship later in South Africa. Arriving in Melbourne, Australia in October 1910, Scott received a telegram from Amundsen stating: "Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic Amundsen," possibly indicating that Scott faced a race to the pole.[68]

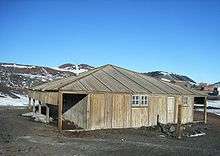

The expedition suffered a series of early misfortunes which hampered the first season's work and impaired preparations for the main polar march. On its journey from New Zealand to the Antarctic, Terra Nova nearly sank in a storm and was then trapped in pack ice for 20 days,[69] far longer than other ships had experienced, which meant a late-season arrival and less time for preparatory work before the Antarctic winter. At Cape Evans, Antarctica, one of the motor sledges was lost during its unloading from the ship, breaking through the sea ice and sinking.[70]

Deteriorating weather conditions and weak, unacclimatised ponies affected the initial depot-laying journey, so that the expedition's main supply point, One Ton Depot, was laid 35 miles (56 km) north of its planned location at 80°S. Lawrence Oates, in charge of the ponies, advised Scott to kill ponies for food and advance the depot to 80°S, which Scott refused to do. Oates is reported as saying to Scott, "Sir, I'm afraid you'll come to regret not taking my advice."[71] Four ponies died during this journey either from the cold or because they slowed the team down and were shot.

On its return to base, the expedition learned of the presence of Amundsen, camped with his crew and a large contingent of dogs in the Bay of Whales, 200 miles (322 km) to their east.[72] Scott conceded that his ponies would not be able to start early enough in the season to compete with Amundsen's cold-tolerant dog teams for the pole, and also acknowledged that the Norwegian's base was closer to the pole by 69 miles (111 km).[73] Wilson was more hopeful,[74] whereas Gran shared Scott's concern.[75] Shortly afterwards, the death toll among the ponies increased to six, three drowning when sea-ice unexpectedly disintegrated, casting in doubt the possibility of reaching the pole at all. However, during the 1911 winter Scott's confidence increased; on 2 August, after the return of a three-man party from their winter journey to Cape Crozier, Scott wrote, "I feel sure we are as near perfection as experience can direct".[76]

Journey to the Pole

Scott outlined his plans for the southern journey to the entire shore party,[77] leaving open who would form the final polar team, according to their performance during the polar travel. Eleven days before Scott's teams set off towards the pole, Scott gave the dog driver Meares the following written orders at Cape Evans dated 20 October 1911 to secure Scott's speedy return from the pole using dogs:

About the first week of February I should like you to start your third journey to the South, the object being to hasten the return of the third Southern unit [the polar party] and give it a chance to catch the ship. The date of your departure must depend on news received from returning units, the extent of the depot of dog food you have been able to leave at One Ton Camp, the state of the dogs, etc ... It looks at present as though you should aim at meeting the returning party about March 1 in Latitude 82 or 82.30[78]

The march south began on 1 November 1911, a caravan of mixed transport groups (motors, dogs, horses), with loaded sledges, travelling at different rates, all designed to support a final group of four men who would make a dash for the Pole. The southbound party steadily reduced in size as successive support teams turned back. Scott reminded the returning Surgeon-Lieutenant Atkinson of the order "to take the two dog-teams south in the event of Meares having to return home, as seemed likely".[79] By 4 January 1912, the last two four-man groups had reached 87°34′S.[80] Scott announced his decision: five men—himself, Wilson, Bowers, Oates and E. Evans) would go forward, the other three (Teddy Evans, William Lashly and Tom Crean) would return. The chosen group marched on, reaching the Pole on 17 January, only to find that Amundsen had preceded them by five weeks. Scott's anguish is indicated in his diary: "The worst has happened [...] All the day dreams must go [...] Great God! This is an awful place".[81]

Last march

The deflated party began the 862 mile (1387 km) return journey on 19 January. "I'm afraid the return journey is going to be dreadfully tiring and monotonous", wrote Scott on that day.[82] The party made good progress despite poor weather, and had completed the Polar Plateau stage of their journey, approximately 300 miles (483 km), by 7 February. In the following days, as the party made the 100 mile (161 km) descent of the Beardmore Glacier, the physical condition of Edgar Evans, which Scott had noted with concern as early as 23 January, declined sharply.[83] A fall on 4 February had left Evans "dull and incapable,"[84] and on 17 February, after another fall, he died near the glacier foot.[85] With 400 miles (644 km) still to travel across the Ross Ice Shelf, Scott's party's prospects steadily worsened as, with deteriorating weather, a puzzling lack of fuel in the depots, hunger and exhaustion, they struggled northward.[86]

Meanwhile, back at Cape Evans, the Terra Nova arrived at the beginning of February, and Atkinson decided to unload the supplies from the ship with his own men rather than set out south with the dogs to meet Scott as ordered.[87] When Atkinson finally did leave south for the planned rendezvous with Scott, he encountered the scurvy-ridden Edward ("Teddy") Evans who needed urgent medical attention. Atkinson therefore tried to send the experienced navigator Wright south to meet Scott, but chief meteorologist Simpson declared he needed Wright for scientific work. Atkinson then decided to send the short-sighted Cherry-Garrard on 25 February, who was not able to navigate, only as far as One Ton depot (which is within sight of Mount Erebus), effectively cancelling Scott's orders for meeting him at latitude 82 or 82.30 on 1 March.[4]

On the return journey from the Pole, Scott reached the 82°S meeting point for the dog teams, 300 miles (483 km) from Hut Point, three days ahead of schedule, noting in his diary for 27 February 1912, "We are naturally always discussing possibility of meeting dogs, where and when, etc. It is a critical position. We may find ourselves in safety at the next depot, but there is a horrid element of doubt." On 2 March, Oates began to suffer from the effects of frostbite and the party's progress slowed as he was increasingly unable to assist in the workload, eventually only able to drag himself alongside the men pulling the sledge. By 10 March the temperature had dropped unexpectedly to below −40 °C (−40 °F).[88]

.png)

In a farewell letter to Sir Edgar Speyer, dated 16 March, Scott wondered whether he had overshot the meeting point and fought the growing suspicion that he had in fact been abandoned by the dog teams: "We very nearly came through, and it's a pity to have missed it, but lately I have felt that we have overshot our mark. No-one is to blame and I hope no attempt will be made to suggest that we had lacked support."[89] On the same day, Oates, whose toes had become frostbitten,[90] voluntarily left the tent and walked to his death.[91] Scott wrote that Oates' last words were "I am just going outside and may be some time".[92]

After walking 20 miles (32 km) farther despite Scott's toes now becoming frostbitten,[93] the three remaining men made their final camp on 19 March, approximately 12.5 miles (20 km) short of One Ton Depot. The next day a fierce blizzard prevented their making any progress.[94] During the next nine days, as their supplies ran out, and with storms still raging outside the tent, Scott and his companions wrote their farewell letters. Scott gave up his diary after 23 March, save for a final entry on 29 March, with its concluding words: "Last entry. For God's sake look after our people".[95] He left letters to Wilson's mother, Bowers' mother, a string of notables including his former commander, Sir George Egerton, his own mother and his wife.[96]

He also wrote his "Message to the Public", primarily a vindication of the expedition's organisation and conduct in which the party's failure is attributed to weather and other misfortunes, but ending on an inspirational note, with these words:

We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last ... Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely, a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for.[97]

Scott is presumed to have died on 29 March 1912, or possibly one day later. The positions of the bodies in the tent when it was discovered eight months later suggested that Scott was the last of the three to die.[98][99][100]

The bodies of Scott and his companions were discovered by a search party on 12 November 1912 and their records retrieved. Tryggve Gran, who was part of the search party, described the scene as, "snowcovered til up above the door, with Scott in the middle, half out of his bagg [sic] ... the frost had made the skin yellow & transparent & I’ve never seen anything worse in my life."[101] Their final camp became their tomb; the tent roof was lowered over the bodies and a high cairn of snow was erected over it, topped by a roughly fashioned cross, erected using Gran's skis.[102] Next to their bodies lay 35 pounds (16 kg) of Glossopteris tree fossils which they had dragged on hand sledges.[103] These were the first ever discovered Antarctic fossils and proved that Antarctica had once been warm and connected to other continents.[1]

In January 1913, before Terra Nova left for home, a large wooden cross was made by the ship's carpenters, inscribed with the names of the lost party and Tennyson's line from his poem Ulysses: "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield", and was erected as a permanent memorial on Observation Hill, overlooking Hut Point.[104]

Reputation

Recognition

The world was informed of the tragedy when Terra Nova reached Oamaru, New Zealand, on 10 February 1913.[105] Within days, Scott became a national icon.[106] A nationalistic spirit was aroused; the London Evening News called for the story to be read to schoolchildren throughout the land,[107] to coincide with the memorial service at St Paul's Cathedral on 14 February. Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts Association, asked: "Are Britons going downhill? No! ... There is plenty of pluck and spirit left in the British after all. Captain Scott and Captain Oates have shown us that".[108]

The expedition's survivors were suitably honoured on their return, with polar medals and promotions for the naval personnel. In place of the knighthood that might have been her husband's had he survived, Kathleen Scott was granted the rank and precedence of a widow of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath.[109][110][111] In 1922, she married Edward Hilton Young, later Lord Kennet, and remained a doughty defender of Scott's reputation until her death, aged 69, in 1947.[112]

An article in The Times, reporting on the glowing tributes paid to Scott in the New York press, claimed that both Amundsen and Shackleton were "[amazed] to hear that such a disaster could overtake a well-organized expedition".[113] On learning the details of Scott's death, Amundsen is reported to have said, "I would gladly forgo any honour or money if thereby I could have saved Scott his terrible death".[114] Scott was the better wordsmith of the two, and the story that spread throughout the world was largely that told by him, with Amundsen's victory reduced in the eyes of many to an unsporting stratagem.[115]

The response to Scott's final plea on behalf of the dependents of the dead was enormous by the standards of the day. The Mansion House Scott Memorial Fund closed at £75,000 (equivalent to £7,480,000 in 2019). This was not equally distributed; Scott's widow, son, mother and sisters received a total of £18,000 (equivalent to £1,795,000 in 2019). Wilson's widow received £8,500 (equivalent to £848,000 in 2019) and Bowers's mother received £4,500 (equivalent to £449,000 in 2019). Edgar Evans's widow, children, and mother received £1,500 (equivalent to £150,000 in 2019) between them.[116]

In the dozen years following the tragedy, more than 30 monuments and memorials were set up in Britain alone. These ranged from simple relics—e.g. Scott's sledging flag in Exeter Cathedral—to the foundation of the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge. Many more were established in other parts of the world, including a statue sculpted by Scott's widow for his New Zealand base in Christchurch.[117]

Modern reactions

Scott's reputation survived the period after World War II, beyond the 50th anniversary of his death.[118] In 1948, the film Scott of the Antarctic was released in cinemas and was the third most popular film in Britain the following year. It portrays the team spirit of the expedition and the harsh Antarctic environment, but also includes critical scenes such as Scott regarding his broken down motors and ruefully remembering Nansen's advice to take only dogs.[119] Evans and Cherry-Garrard were the only surviving expedition members to refuse participation in the film, but both re-published their respective books in its wake.

In 1966, Reginald Pound, the first biographer given access to Scott's original sledging journal, revealed personal failings which cast a new light on Scott,[118] although Pound continued to endorse his heroism, writing of "a splendid sanity that would not be subdued".[120] Another book critical of Scott, David Thomson's Scott's Men, was released in 1977. In Thomson's view, Scott was not a great man, "at least, not until near the end";[121] his planning is described as "haphazard" and "flawed",[122] his leadership characterised by lack of foresight.[123] Thus by the late 1970s, in Jones's words, "Scott's complex personality had been revealed and his methods questioned".[118]

In 1979 came the first extreme[124] attack on Scott, from Roland Huntford's dual biography Scott and Amundsen in which Scott is depicted as a "heroic bungler".[125] Huntford's thesis had an immediate impact, becoming the contemporary orthodoxy.[126] After Huntford's book, several other mostly negative books about Captain Scott were published; Francis Spufford, in a 1996 history not wholly antagonistic to Scott, refers to "devastating evidence of bungling",[127] concluding that "Scott doomed his companions, then covered his tracks with rhetoric".[128] Travel writer Paul Theroux summarised Scott as "confused and demoralised ... an enigma to his men, unprepared and a bungler".[129] This decline in Scott's reputation was accompanied by a corresponding rise in that of his erstwhile rival Shackleton, at first in the United States but eventually in Britain as well.[130] A 2002 nationwide poll in the United Kingdom to discover the "100 Greatest Britons" showed Shackleton in eleventh place, Scott well down the list at 54th.[130]

The 21st century has seen a shift of opinion in Scott's favour, in what cultural historian Stephanie Barczewski calls "a revision of the revisionist view".[131] Meteorologist Susan Solomon's 2001 account The Coldest March ties the fate of Scott's party to the extraordinarily adverse Barrier weather conditions of February and March 1912 rather than to personal or organisational failings and, while not entirely questioning any criticism of Scott,[132][133] Solomon principally characterises the criticism as the "Myth of Scott as a bungler". [134]

In 2005 David Crane published a new Scott biography in which he comes to the conclusion that Scott is possibly the only figure in polar history except Lawrence Oates "so wholly obscured by legend".[135] According to Barczewski, he goes some way towards an assessment of Scott "free from the baggage of earlier interpretations".[131] What has happened to Scott's reputation, Crane argues, derives from the way the world has changed since the "hopeless heroism and obscene waste" of the First World War. At the time of Scott's death, people clutched at the proof he gave that the qualities that once made Britain great were not extinct, but with the knowledge of what lay only two years ahead, the ideals of duty, self-sacrifice, discipline, patriotism and hierarchy associated with his tragedy take on a different and more sinister colouring.[136]

Crane's main achievement, according to Barczewski, is the restoration of Scott's humanity, "far more effectively than either Fiennes's stridency or Solomon's scientific data."[131] Daily Telegraph columnist Jasper Rees, likening the changes in explorers' reputations to climatic variations, suggests that "in the current Antarctic weather report, Scott is enjoying his first spell in the sun for twenty-five years".[137] The New York Times Book Review was more critical, pointing out Crane's support for Scott's account regarding the circumstances of the freeing of the Discovery from the pack ice, and concluded that "For all the many attractions of his book, David Crane offers no answers that convincingly exonerate Scott from a significant share of responsibility for his own demise."[138]

In 2012, Karen May published her discovery that Scott had issued written orders, before his march to the Pole, for Meares to meet the returning party with dog-teams, in contrast to Huntford's assertion in 1979 that Scott issued those vital instructions only as a casual oral order to Evans during the march to the Pole. According to May, "Huntford's scenario was pure invention based on an error; it has led a number of polar historians down a regrettable false trail".[139]

See also

References

Footnotes

- "Antarctic Fossils | Expeditions". expeditions.fieldmuseum.org. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Four things Captain Scott found in Antarctica". BBC. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- Crane 2005, p. 82.

- May 2013.

- Crane 2005, pp. 14–15.

- Crane 2005, p. 22.

- "Scott's Expedition". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 17.

- Crane 2005, p. 23.

- Crane 2005, p. 34.

- Crane 2005, p. 50.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 121–123.

- Crane 2005, pp. 39–40.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 21.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 22.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 23.

- Crane 2005, p. 59.

- Crane 2005, p. 84.

- Crane 2005, p. 90.

- Preston 1999, pp. 28–29.

- Crane 2005, p. 63.

- "The Discovery – Inspection by the King and Queen". The Times (36526). London. 6 August 1901. p. 10.

- "No. 27346". The London Gazette. 16 August 1901. p. 5409.

- Scott 1905, vol 1, p. 170.

- "The dog-team is invested with a capacity of work which is beyond the emulation of party of men ... This method of using dogs is one which can only be adopted with reluctance. One cannot calmly contemplate the murder of animals which possess such intelligence and individuality" RF Scott The Voyage of the Discovery Vol I, Smith Elder & Co, London 1905, p. 465.

- Scott 1905, pp. 211–227.

- Crane 2005, pp. 161–167.

- Preston 1999, pp. 60–67.

- Crane 2005, p. 270.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 148.

- Huntford 1985, pp. 229–230.

- Crane 2005, pp. 392–393.

- Preston 1999, pp. 78–79.

- Preston 1999, pp. 67–68.

- Crane 2005, pp. 240–241.

- Crane 2005, p. 310.

- Crane 2005, pp. 396–397.

- Preston 1999, p. 113.

- Crane 2005, p. 309.

- Preston 1999, pp. 83–84.

- Preston 1999, p. 86.

- Crane 2005, p. 334.

- Burt 1988, p. 211.

- Preston 1999, p. 87.

- Crane 2005, p. 335.

- Riffenburgh 2005, pp. 113–114.

- Ackerman, Naomi; Dex, Robert (15 October 2019). "Antarctic explorer Scott's letter of complaint about rival Shackleton to go on display in exhibition". Evening Standard. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Hoare, Callum (17 October 2019). "Antarctica discovery: Century-old letter reveals shock find after first exploration". Express. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Crane 2005, pp. 335, 341.

- Barczewski 2007, pp. 52–53.

- Fiennes 2003, pp. 144–145.

- Riffenburgh 2005, p. 118.

- Crane 2005, p. 344.

- Preston 1999, p. 94.

- Crane 2005, p. 350.

- Crane 2005, pp. 362–366.

- Crane 2005, pp. 373–374.

- Crane 2005, p. 387.

- Preston 1999, pp. 100–101.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 161.

- Crane 2005, pp. 397–399.

- RF Scott (1908) The Sledging Problem in the Antarctic, Men versus Motors

- Roland Huntford (2003) Scott and Amundsen. Their Race to the South Pole. The Last Place on Earth. Abacus, London, p. 224.

- Preston 1999, p. 107.

- Crane 2005, pp. 432–433.

- Roland Huntford (2003) Scott and Amundsen. Their Race to the South Pole. The Last Place on Earth. Abacus, London, p. 262.

- Preston 1999, p. 112.

- Crane 2005, pp. 425–428.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 30–71.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 106–107.

- Crane 2005, p. 466.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 187–188.

- Scott's diary, 22 February 1911: "The proper, as well as wiser, course for us is to proceed exactly as though this had not happened. To go forward and do our best for the honour of the country without fear or panic. There is no doubt that Amundsen's plan is a serious menace to ours. He has a shorter distance to the Pole by 60 miles (100 km)– I never thought he could have got so many dogs safely to the ice. His plan for running them seems excellent. But above all he can start his journey early in the season – an impossible condition with ponies."

- Wilson's diary "As for Amundsen's prospects of reaching the Pole, I don't think they are very good ... I don't think he knows how bad an effect the monotony and the hard travelling surface of the Barrier is to animals," cited from Ranulph Fiennes Captain Scott Hodder and Stoughton, London 2003 p. 219.

- Tryggve Gran's diary "If we reach the Pole, then Amundsen will reach the Pole, and weeks earlier. Our prospects are thus not exactly promising. The only thing that can save Scott is if an accident happens to Amundsen." cited from Ranulph Fiennes Captain Scott Hodder and Stoughton, London 2003 p219f

- Huxley 1913a, p. 369.

- Huxley 1913a, p. 407.

- Evans 1949, pp. 187–188.

- Cherry-Garrard 1970, p. 424.

- Huxley 1913a, p. 528.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 543–544.

- Scott's diary, 19 January 1912

- Huxley 1913a, p. 551.

- Huxley 1913a, p. 560.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 572–573.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 574–580.

- "Karen May & Peter Forster on Cherry-Garrard's 1948 postscript", The Telegraph, accessed 12 October 2014.

- Solomon 2001, pp. 292–294.

- May 2013, pp. 1–19.

- "Oates disclosed his feet, the toes showing very bad indeed, evidently bitten by the late temperatures" Scott diary entry, 2 March 1912. "The result is telling on ... Oates, whose feet are in a wretched condition. One swelled up tremendously last night and he is very lame this morning" Scott diary entry 5 March 1912. "Titus Oates is very near the end" – Scott diary entry, 17 March 1912.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 591–592.

- Huxley 1913a, p. 592.

- "My right foot has gone, nearly all the toes – two days ago I was proud possessor of best feet. These are the steps of my downfall. Like an ass I mixed a small spoonful of curry powder with my melted pemmican – it gave me violent indigestion. I lay awake and in pain all night; woke and felt done on the march; foot went and I didn't know it. A very small measure of neglect and have a foot which is not pleasant to contemplate." Scott's diary 18 March 1912

- Huxley 1913a, p. 594.

- Huxley 1913a, p. 595.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 597–604.

- Huxley 1913a, pp. 605–607.

- Huxley 1913a, p. 596.

- Jones 2003, p. 126.

- Huntford 1985, p. 509.

- Flood, Alisonn. "Antarctic diary records horror at finding Captain Scott's body". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- Huxley 1913b, pp. 345–347.

- Coyne, Jerry (2010). Why Evolution is True. 375 Hudson St., New York, New York 10014, U.S.A: Penguin Group (USA). p. 99. ISBN 9780143116646.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Huxley 1913b, p. 398.

- Crane 2005, pp. 1–2.

- Preston 1999, p. 230.

- Jones 2003, pp. 199–201.

- Jones 2003, p. 204.

- Preston 1999, p. 231.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 383.

- Huntford 1985, p. 523.

- Preston 1999, p. 232.

- Unattributed (11 February 1913). "The Polar Disaster. Captain Scott's Career, Naval Officer And Explorer". The Times. p. 10.

- Huntford 1985, p. 525.

- Amundsen 1976, Publisher's note.

- Jones 2003, pp. 106–108.

- Jones 2003, pp. 295–296.

- Jones 2003, pp. 287–289.

- "BFI Screenonline: Scott of the Antarctic (1948)". www.screenonline.org.uk.

- Pound 1966, pp. 285–286.

- Thomson 1977, preface, xiii.

- Thomson 1977, pp. 153, 218.

- Thomson 1977, p. 233.

- Fiennes 2003, p. 386 Francis Spufford, author of It may be some time wrote: "Huntford's assault on Scott was so extreme it plainly toppled over into absurdity"

- Huntford 1985, p. 527.

- Jones 2003, p. 8.

- Spufford 1997, p. 5.

- Spufford 1997, pp. 104–105.

- Barczewski 2007, p. 260.

- Barczewski 2007, p. 283.

- Barczewski 2007, pp. 305–311.

- Solomon 2001, pp. 309–327.

- Barczewski 2007, p. 306.

- Solomon 2001, p. xvi, xvii, 124, 129.

- Crane 2005, p. 373.

- Crane 2005, p. 12.

- Rees 2004.

- Dore 2006.

- May 2013, pp. 72–90.

Bibliography

- Amundsen, R. (1976) [1912]. The South Pole. London: C. Hurst & Company. ISBN 9780903983471.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barczewski, S. (2007). Antarctic Destinies: Scott, Shackleton and the Changing Face of Heroism. London: Hembledon Continuum. ISBN 9781847251923.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cherry-Garrard, A. (1970). The Worst Journey in the World (1965 ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 9780140095012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crane, D. (2005). Scott of the Antarctic: A Life of Courage, and Tragedy in the Extreme South. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780007150687.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, E. R. G. R. (1949). South with Scott. London: Collins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiennes, R. (2003). Captain Scott. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340826973.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huntford, R. (1985). The Last Place on Earth. London: Pan Books. ISBN 9780330288163. OCLC 12976972.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huxley, L., ed. (1913a). Scott's Last Expedition, Volume I. London: Smith, Elder & Co. OCLC 1522514.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huxley, L., ed. (1913b). Scott's Last Expedition, Volume II. London: Smith, Elder & Co. OCLC 1522514.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, M. (2003). The Last Great Quest: Captain Scott's Antarctic Sacrifice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192804839. OCLC 59303598.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pound, R. (1966). Scott of the Antarctic. London: Cassell & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Preston, D. (1999). A First Rate Tragedy: Captain Scott's Antarctic Expeditions (paperback ed.). London: Constable. ISBN 9780094795303.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riffenburgh, B. (2005). Nimrod: Ernest Shackleton. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747572534.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, R. F. (1905). The Voyage of the Discovery. London: Nelson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sienicki, Krzysztof (2016). Captain Scott: Icy Deceits and Untold Realities (Three Volumes Bound as One). Open Academic Press. ISBN 978-8394452001.

- Solomon, S. (2001). The Coldest March: Scott's Fatal Antarctic Expedition. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300089677. OCLC 45661501.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spufford, F. (1997). I May Be Some Time: Ice and the English Imagination. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571179510.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomson, D. (1977). Scott's Men. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713910346.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turney, Chris (2012). 1912: The Year The World Discovered Antarctica. Melbourne: Text Publishing. ISBN 978-1-9219-2272-5.

Online

- Dore, J. (3 December 2006). "Crucible of Ice". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- May, K. (January 2013). "Could Captain Scott have been saved? Revisiting Scott's last expedition". Polar Record. 49 (1): 72–90. doi:10.1017/S0032247411000751.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rees, J. (19 December 2004). "Ice in our Hearts". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 October 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Falcon Scott. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Falcon Scott |

- Works by Robert Falcon Scott at Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Works by Robert Falcon Scott at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Robert Falcon Scott at Open Library

- Works by Robert Falcon Scott at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Falcon Scott at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Robert Falcon Scott in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

.svg.png)