Argentine Navy

The Argentine Navy (ARA; Spanish: Armada de la República Argentina)[NB 1][4] is the navy of Argentina. It is one of the three branches of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic, together with the Army and the Air Force.

| Navy of the Argentine Republic | |

|---|---|

| Armada de la República Argentina | |

.svg.png) Shield, the red Phrygian cap symbolizing pursuit of liberty. | |

| Founded | 25 May 1810 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Navy |

| Size | 18,368 (2018)[1] |

| Part of | Ministry of Defense |

| Main Base | Puerto Belgrano Naval Base |

| Motto(s) | Go under rather than surrender the flag |

| Colors | Light blue and white |

| March | Navy March[2] |

| Anniversaries | May 17 (Navy Day) |

| Fleet | 2 submarines 4 destroyers 9 corvettes 11 patrol boats 2 amphibious warfare ships 19 auxiliary ships |

| Engagements | Argentine War of Independence Cisplatine War Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata Paraguayan War Revolución Libertadora Falklands War Gulf War Operation Uphold Democracy |

| Website | http://www.armada.mil.ar/ |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | President Alberto Fernández |

| Chief of General Staff | Vice-Admiral José Luis Villán |

| Deputy Chief of General Staff | Vice-Admiral Eduardo Alberto Fondevila Sancet |

| Commander Training and Enlistment of the Navy | Rear-Admiral Fabián Gerardo D´Angelo |

| Commander Marine Corps | Ship-of-the-line Captain Humberto Mario Dobler |

| Commander Naval Aviation | Ship-of-the-line Captain Sergio Mariot |

| Insignia | |

| Naval Jack |  |

| Naval Ensign |  |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Attack | Super Étendard[3] AS-555 Fennec |

| Patrol | P-3 Orion BE-200 Cormorán S-2 Tracker |

| Trainer | T-34 Mentor |

| Transport | Fokker F-28 PC-6 Porter SH-3 Sea King |

The Argentine Navy day is celebrated on May 17, anniversary of the victory in 1814 at the Battle of Montevideo over the Spanish fleet during the war of Independence.[5]

History

19th century

The Argentine Navy was created in the aftermath of the May Revolution of May 25, 1810, which started the war for independence from Spain. The navy was first created to support Manuel Belgrano in the Paraguay campaign, but it was sunk by ships from Montevideo, and did not take part in that conflict. Renewed conflicts with Montevideo led to the creation of a second fleet, which participated in the capture of the city. As Buenos Aires had little maritime history, most men in the navy were from other nations, such as the Irish-born admiral William Brown, who directed the operation. As the cost of maintaining a navy was too high, most of the Argentine naval forces were composed of privateers.

Brown led the Argentine navy in further naval conflicts at the War with Brazil and the Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata.

In the 1870s the Argentine Navy began modernizing itself. At the close of the century, the force included:

- 5 armoured cruisers

- 4 coastal defence ironclads

- 3 second-class, high-speed, British-built cruisers

- 7 modern small cruisers and gunboats

- 4 destroyers and

- 22 torpedo boats.[6]

The most powerful ships at this time included the Italian-built Garibaldi and her sister ships: General Belgrano, Pueyrredón, and San Martín, each at over 6,000 tons. Three older ironclads, Almirante Brown, Independencia, and Libertad dated from the 1880s and early 1890s.[7]

The navy's ships were built primarily in Italy, Britain, France, and Spain, and were operated by over 600 officers and 7,760 seamen. These were supported by a battalion of marines and an artillery battery.[8]

20th century

Argentina remained neutral in both world wars. In 1940 Argentina's navy was ranked the eighth most powerful in the world (after the European powers, Japan, and the United States) and the largest in Latin America. A ten-year building programme costing $60 million had produced a force of 14,500 sailors and over a thousand officers. The fleet included two First World War-era (but modernized) American-built Rivadavia-class battleships, three modern cruisers, a dozen British-built destroyers, and three submarines, plus minelayers, minesweepers, coastal defence ships, and gunboats. A naval air force was also in operation.[9]

In the postwar period, Naval Aviation and Marine units were put under direct Navy command. With Brazil, Argentina is one of two South American countries to have operated two aircraft carriers: the ARA Independencia and ARA Veinticinco de Mayo.

The Argentine Navy has been traditionally heavily involved in fishery protection, helping the Coast Guard: most notably in 1966 a destroyer fired on and holed a Soviet trawler that had refused to be escorted to Mar del Plata, in the 1970s there were four more incidents with Soviet and Bulgarian ships[10] followed by other incidents such as the sinking of the Chian-der 3.[11][12][13]

The Navy also took part in all military coups in Argentina through the 20th century. During the 1976 to 1983 dictatorship, Navy personnel were involved in the Dirty War in which thousands of people were kidnapped, tortured and killed by the forces of the military junta. The Navy School of Mechanics, known as ESMA, was a notorious centre for torture. Among their more well-known victims were the Swedish teenager Dagmar Hagelin, and French nuns Alice Domon and Léonie Duquet (In October 2007 the Argentine Navy formally handed possession of the school to human rights groups to turn it into a memorial museum).

During this regime, the Navy was also the main supporter of a military solution for the country's two longest-standing disputes: the Beagle Conflict with Chile and the Falkland Islands (Spanish: Islas Malvinas) with the United Kingdom.

Falklands War

During the 1982 Falklands conflict (termed by the Argentines Guerra de las Malvinas / Guerra del Atlántico Sur) the Main Argentine Naval Fleet consisted of modernised World War II era ships (one GUPPY-type submarine, one British-built Colossus-class carrier, a cruiser, and four destroyers), and newer vessels: two Type 42 destroyers, three French-built corvettes, and one German-built Type 209 submarine. This fleet was supported by several ELMA tankers and transports, as well an ice breaker and a polar transport ship.

New German MEKO type destroyers, corvettes, and Thyssen-Nordseewerke (Type TR-1700) submarines were still under construction at the time.

Despite leading the invasion of the Falkland Islands, in both strategic and tactical aspects the Argentine fleet played only a small part in the subsequent conflict with the Royal Navy. After HMS Conqueror sank the ARA General Belgrano, the Argentine surface fleet did not venture from a 12-mile (22.2 km) coastal limit imposed by the British because of the threat posed by the Royal Navy nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs).

The Argentine Navy's contributions to the war were principally the initial amphibious assaults on 2 and 3 April; naval aviation Super Étendards armed with Exocet missiles, which sank Sheffield and the Atlantic Conveyor; Skyhawks, which sank HMS Ardent (F184); and the Marines, with the 5th Marine Corps Battalion defending Mount Tumbledown. In addition, the Type 42 destroyer ARA Santísima Trinidad, operating off Staten Island, played an important part in the destruction of the British landing ship Sir Galahad on 8 June,;[14] a land-based Exocet battery outside Port Stanley scored a direct hit on HMS Glamorgan on 11 June; and a Marine Tigercat SAM put a Royal Air Force Harrier (XW 919) out of action on 12 June.[15] Naval aviation also carried out intensive maritime patrols, searching to locate the British fleet for the strike aircraft and British submarines for the anti-submarine Sea King helicopters, while their Lockheed L-188 Electra and Fokker F-28 Fellowship transports reinforced the Port Stanley garrison and evacuated the wounded.

The ARA San Luis submarine also played a strategic role, nearly sinking the frigate HMS Arrow on 10 May,[16] although she scored no hits. The submarine ARA Santa Fe, after a successful resupply mission, was attacked and disabled off South Georgia, where her crew then surrendered along with the Argentine detachment at Grytviken. She was later scuttled by the British.

Aftermath of the Falklands war

.jpg)

The core of the fleet was reformed with the retirement of all the World War II-era Fletcher and Gearing-class destroyers and their replacement with the MEKO 360 and 140 classes designed by the German shipyard Blohm + Voss.

Also, the submarine force greatly reinforced their assets with the introduction of the Thyssen-Nordseewerke (TR-1700) class. Although the original programme called for six units with the last four to be built in Argentina, only the two built in Germany were delivered.

The amphibious force was drastically affected with the retirement of their only LST landing ship ARA Cabo San Antonio and replacement by a modified cargo vessel, the ARA Bahía San Blas. This situation improved in 2006 with the delivery by France of the first of the LPD Ouragan-class landing platform docks but the whole operation was placed on hold by the Argentine Government due to asbestos concerns. In 2010 France offered the Foudre (L9011) instead.[17]

_and_an_Argentinean_P-3_aircraft_patrol_the_northern_approach_to_the_Panama_Canal.jpg)

France also transferred the Durance (A629), now ARA Patagonia (B-1), multi-product replenishment ship (AOR).

In 1988 the A-4 Skyhawk aircraft were withdrawn, leaving the Super Étendard as the only fighter jets in the navy inventory. The already-paid-for A-4Hs bought in Israel as their replacement could not be delivered due to the embargo imposed by the United States after the war. Instead IAI used the money to refurbish the S-2E Trackers to the S-2T Turbo Tracker variant currently in service.

In the 1990s, the embargo was lifted and the Lockheed L-188 Electras (civilian aircraft converted for maritime patrol) were finally retired and replaced with similar P-3B Orions and civilian Beechcraft King Air Model 200 were locally converted to the MP variant.

In 2000 the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo was decommissioned without replacement, although the navy maintains the air group of Super Étendard jets and S-2 Trackers that routinely operated from the Brazilian Navy aircraft carrier São PauloARAEX video or United States Navy carriers when they are in transit in the south Atlantic during Gringo-Gaucho manoeuvers.

Gulf War and nineties

Argentina was the only Latin American country to participate in the 1991 Gulf War, sending a destroyer and a corvette in a first deployment and a supply ship and another corvette later to participate in the United Nations blockade and sea control effort in the gulf. Operación Alfil ("English: Operation [Chess] Bishop"), as it was known, carried out more than 700 interceptions and sailed 25,000 miles in the operations theatre.

From 1990 to 1992, the Baradero-class patrol boats were deployed under UN mandate ONUCA to the Gulf of Fonseca in Central America.[18] In 1994, the three Drummond-class corvettes participated in Operation Uphold Democracy in Haiti.[19]

21st century

In 2003, for the first time, the Argentine Navy (classified as major non-NATO ally) interoperated with a United States Navy battle group when the destroyer ARA Sarandí (D-13) joined the USS Enterprise Carrier Strike Group and Destroyer Squadron 18 as a part of Exercise Solid Step during their tour in the Mediterranean Sea.

In 2010 the construction of four 1,800 ton offshore patrol ships was announced,[20] but never started. Also in May 2010, Defence Minister Nilda Garre announced that the Navy would continue working on a system that would enable the launch of Exocet missiles from the Navy's P-3 Orion aircraft. In addition, the financing of the local development and construction of a coastal naval defence system that may also be based on the use of Exocet missiles similar to the Excalibur system.

In October 2012 the Navy's sail training ship ARA Libertad was seized under court order in Ghana by creditors of Argentina's debt default in 2002.[21] On 15 December 2012 the UN International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled unanimously that the ship had immunity as a military vessel, and ordered that "Ghana should forthwith and unconditionally release the frigate ARA Libertad"[22][23] Four days later Libertad was released from Tema and arrived to the port of Mar del Plata on 9 January 2013.[24]

The Argentine Navy is under-funded and struggling to meet maintenance and training requirements; as a result, only 15 of its 42 vessels are in a condition to sail. The 2013 defence budget allowed for the 15 operational vessels to each spend less than 11 days at sea, while the submarines averaged just over 6 hours submerged in the whole of 2012.[25] ARA Espora spent 73 days in late 2012 stranded in South Africa for lack of spares. The Almirante Brown-class destroyers are short of spares and their ordnance has expired, while the Antarctic patrol ship ARA Almirante Irizar had been under repair for 10 years because of a fire.[25] On 23 January 2013 the Type 42 destroyer ARA Santísima Trinidad sank at her moorings after having been mothballed for ten years.[26]

The Argentine Navy participates in joint exercises with other friendly navies including Brazil, United States, Spain, France, Canada, South Africa,[27] Italy, Uruguay, and, since the 1990s, Chile. The exercises are routinely held to develop a common operational doctrine. Every year the Argentine and Chilean Navies participate in the Patrulla Antártica Naval Combinada (English: Joint Antarctic Naval Patrol) to guarantee safety to all tourist and scientific ships in transit within the Antarctic Peninsula, where the Navy is also directly responsible for maintaining the Argentine bases there.

On 15 November 2017, the ARA San Juan (S-42) stopped communicating during a routine transit to port following a military exercise. A search was launched by ISMERLO, however after 15 days of searching the Argentine Navy declared the end of the rescue operation, and solely focused on the recovery of the submarine—not the crew. 44 personnel were on the submarine when it disappeared.[28] The final inform made by Argentinian congressmen stated that president Mauricio Macri and his defence minister had political responsibilities about what happened to ARA San Juan.[29]

Since summer 2019, the governments of Brazil and Argentina have been working on a transfer deal of the four Tupi IKL209/1400 submarines currently operated by the Brazilian Navy. Two Subs are currently non operational pending repairs, the other two are still active pending their replacement by the 4 Scorpene type Submarines currently under construction. However, in the early 2000s they had been upgraded with new combat systems by Lockheed Martin Maritime Systems and Sensors. This gave the submarines the ability to carry and fire the MK 48 MOD 6AT ADCAP Torpedo. Although there are some reservations about the deal, the defense ministers and admirals of the Argentine Navy are enthusiastic about moving forward with it. The submarines can easily be repaired and serviced in the Tandanor drydock facility. If this deal succeeds it will allow Argentina to replace the two remaining submarines ARA Salta S-31, and ASA Santa Cruz S-41 currently in service with its fleet. It will also bolster its submarine force strength and its strategic position in the South Atlantic.[30][31][32]

Argentina is currently working on a procurement of four P-3C Orion aircraft from US Navy surplus stocks. Argentina's current fleet of P-3B's are non operational. The package deal was approved in September 2019. The US State Department has cleared the transaction of $78.03m to be carried out as part of a foreign military sale. It includes the delivery of related equipment and services. Argentina will receive four turboprop engines for the aircraft and an additional four turboprop engines. It will also receive communications and radar equipment, Infrared/Electro-optic equipment, and aviation life support systems. The US will provide spares plus repairs, aircraft depot maintenance, and logistical support. Contractors for the deal include Logistic Services International, Lockheed Martin, Rockwell Collins and Eagle Systems. These newer Orions will be up to the latest Orion standard, and provide Argentina with a much needed boost in anti-submarine and maritime surveillance missions.[33]

In 2020, Argentina national government created an interministerial committee with the objective of reassuring national oceans' sovereignty. In 2020, the Ministry of Defence informed Congress of a desire to acquire a Landing Platform Dock (LPD) as well as two naval transport vessels to increase logistical capacity, including in relation to the country's claims and presence in the Antarctic.[34] Foreign overfishing is a concern and the Argentine Navy recently captured at least two foreign ships allegedly illegally fishing in the South Atlantic.[35] Partially to address this, a project for the reactivation of two Meko 140-class corvettes was reportedly under development.[36] Nevertheless, it was not clear that these projects could be effectively funded.

Structure

The Argentine navy has four main commands: High Seas Fleet, Submarine Force, Naval Aviation, and Naval Infantry (Marines).

Sea Fleet

Puerto Belgrano Naval Base (Spanish: Base Naval Puerto Belgrano, abbreviated BNPB) is the largest naval base of the Argentine Navy, situated next to Punta Alta, near Bahía Blanca, about 700 km (435 mi) south of Buenos Aires. Most of the fleet is based there.

Submarine Force

The Submarine Force Command (Spanish: Comando de la Fuerza de Submarinos, abbreviated COFS) was created when the Navy first started using submarines in 1927. As of 2013 the force is based at Mar del Plata. The Tactical Divers Group is also under the submarine force command structure.

Naval Aviation

The Naval Aviation Command (Spanish: Comando de Aviación Naval, abbreviated COAN) is the naval aviation branch. Argentina is one of two South American countries to have operated two aircraft carriers. Naval Aviation used the Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard fighter, no longer in service, in the Falklands War.

Naval Infantry

The Naval Infantry Command (Comando de Infantería de Marina) is the Argentine Navy's marine branch. Naval infantry have the same rank, insignia, and titles as the rest of the Navy, and are deployed abroad on UN peacekeeping missions.[37][38]

Hydrographic Service

The Argentine Naval Hydrographic Service (Spanish: Servicio de Hidrografía Naval, abbreviated SHN) provides national hydrographics services.

Ranks

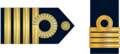

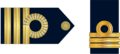

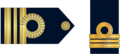

Officers

Rank insignia consists of a variable number of gold-braid stripes worn on the sleeve cuffs or on shoulder-boards. Officers may be distinguished by the characteristic loop of the top stripe (in the manner of British Royal Navy officers). Combat uniforms may include metal pin-on or embroidered collar rank insignia. Rank insignia is worn on the chest when in shipboard or flying coveralls.

Officers are commissioned in either the Command (line) Corps (those who attend the Escuela Naval Militar- Naval College) or the Staff Corps (Professional Officers who only attend a short course in the Naval Academy after getting a civilian degree, except for the Paymasters who indeed attend the Naval College).

The Line Corps is divided into three branches: the Naval branch (including Surface Warfare, Submarine Warfare and Naval Aviation sub-branches), the Marine Corps branch, and Executive -Engineering- branch. Line Corps' reserve officers are considered Restricted Line ( Escalafon Complementario ) officers in any of the Warfare Communities (Surface, Submarine, Marines, Aviation and Propulsion), and can only raise to OF-4 rank ( Capitan de Fragata ).

All Line Corps officers were distinctive branch/sub-branch insignia on the right breast. Some Staff Corps officers also wear specialisation badges (Aviation, Surface, Submarine and Marines). Other common insignia is the Naval War College insignia, parachute wings, etc., also worn on the right breast. Medals and Ribbons, if awarded, are worn on the left breast, just above the chest pocket. The rank insignia of Staff Corps' officers is placed over a background colour denoting the wearer's field, such as purple (Chaplains), blue (Engineers), red (Health Corps), white (Paymasters), green (Judge Advocate Officers), brown (Technical Officers, promoted from the ranks) and grey (special branch). The background colour for Command Corps officers is navy blue/black.

| Insignia | Argentine Rank (in Spanish) | Argentine Rank (in English) | Equivalent Royal Navy Rank | Equivalent US Navy Rank | NATO Rank Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Almirante | Admiral | Admiral | Admiral | OF-9 |

|

Vicealmirante | Vice Admiral | Vice Admiral | Vice Admiral | OF-8 |

|

Contraalmirante | Counter Admiral | Rear Admiral | Rear Admiral (Upper Half) | OF-7 |

|

Comodoro de Marina | Commodore of the Navy | Commodore | Rear Admiral (Lower Half) | OF-6 |

|

Capitán de Navío | Ship-of-the-Line Captain | Captain | Captain | OF-5 |

|

Capitán de Fragata | Frigate Captain | Commander | Commander | OF-4 |

|

Capitán de Corbeta | Corvette Captain | Lieutenant-Commander | Lieutenant Commander | OF-3 |

|

Teniente de Navío | Ship-of-the-Line Lieutenant | Lieutenant | Lieutenant | OF-2 |

|

Teniente de Fragata | Frigate Lieutenant | Sub-Lieutenant | Lieutenant (Junior Grade) | OF-1 |

|

Teniente de Corbeta | Corvette Lieutenant | Acting Sub-Lieutenant | Ensign | OF-1 |

|

Guardiamarina | Midshipman | Midshipman | Midshipman | OF-D |

Enlisted ratings and Non-Commissioned Officers

Other ranks' insignia (not including Seamen) is worn on either shoulderboards or breast or sleeve patches. Seamen and Seamen Recruits wear their insignia on their sleeves. The shoulderboards denote the wearer's specialty.

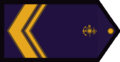

| Insignia | Argentine Rank (in Spanish) | Argentine Rank (in English) | Equivalent RN Rank (approximate) | Equivalent USN Rank (approximate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suboficial Mayor | Sub-Officer Major | Warrant Officer 1 | Master Chief Petty Officer, Command Master Chief Petty Officer |

|

Suboficial Principal | Principal Sub-Officer | Warrant Officer 2 | Senior Chief Petty Officer |

|

Suboficial Primero | Sub-Officer First Class | Chief Petty Officer | Chief Petty Officer |

|

Suboficial Segundo | Sub-Officer Second Class | Petty Officer | Petty Officer 1st Class |

|

Cabo Principal | Principal Corporal | Leading Seaman/Rate/Hand | Petty Officer 2nd Class |

|

Cabo Primero | Corporal First Class | Able Seaman 1st Class | Petty Officer 3rd Class |

|

Cabo Segundo | Corporal Second Class | Able Seaman 2nd Class | Seaman |

|

Marinero Primero | Seaman | Ordinary Seaman | Seaman Apprentice |

|

Marinero Segundo | Seaman Recruit | (No equivalent) | Seaman Recruit |

Uniform

Beards

Following a global trend, Argentine armed forces have prohibited beards since the 1920s. This was reinforced in the Cold War era when they were deemed synonymous with leftist leanings. The only exception were Antarctic service within the three armed forces as a protection from cold weather, and submarine service within the Navy as a way of saving water. However, shaving was mandatory upon return to headquarters.

In 2000 the Navy broke with this tradition within the Argentine armed forces as Adm. Joaquín Stella, then Navy Chief of Staff allowed beards for officers with ranks above Teniente de Corbeta (Second Lieutenant (rank)), according to Section 1.10.1.1 of the Navy Uniform regulations (R.A-1-001). Adm. Stella gave the example himself by becoming the first bearded Argentine admiral since Adm. Sáenz Valiente in the 1920s. Non commissioned officers can wear beards from Suboficial Segundo rank, and upwards. However, beards were prohibited again in 2016, except for some specific office positions.

Equipment

See also

- Argentine Army

- Argentine Air Force

- Argentine Naval Aviation

- Argentine Army Aviation

- Argentine naval forces in the Falklands War

- List of ships of the Argentine Navy

- List of auxiliary ships of the Argentine Navy

- List of senior officers of the Argentine Navy

Notes

- In the native Spanish, the navy is known as Armada de la República Argentina. This also forms the basis for the navy's ship prefix "ARA".

References

Citations

- "Argentina hace publica la cantidad de personal militar en sus fuerzas". zona-militar.com. 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- From the 1936 movie La muchachada de a bordo composed by Manuel Romero and Abraham Soifer

- https://www.argentina.gob.ar/armada/aviacion-naval/unidades

- "The Argentine Navy's Recent Past in Photographs". Warship International (1): 84–88. 1988.

- "Historia de la Armada Argentina (in Spanish)". ara.mil.ar. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Keltie, J.S., ed. The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1900. New York: Macmillan, 1900. p 349.

- Keltie 1900, p. 349.

- Keltie 1900, p. 349–350.

- Associated Press. "Plan Big Navy for Argentina". Youngstown Vindicator March 10, 1940. (Retrieved via Google News 10/25/10).

- Conway's All the World Fighting Ships 1947–1995

- "Persecución y captura de un pesquero". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Incendian y hunden un pesquero para evitar su captura". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Para evitar su captura, el capitán de un pesquero hundió el barco". lanacion.com.ar. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- "Vice-Admiral Lombardo ... states that the Type 42 destroyer Santisima Trinidad was off the Argentine coast that day carrying out radio interference operations on the frequencies used by the British air controllers." The Fight for the Malvinas, pp. 211-212, Martin Middlebrook, Penguin, 1990

- La difesa argentina replicò con prontezza, danneggiando un Harrier con un obsoleto missile Tigercat, che esplose dietro il suo bersaglio. Rivista aeronautica, p. 110, Tomo 18, Ministero dell'aeronautica, 2005

- "A few minutes later, when the frigates were close to the submarine, a 'small metallic explosion' was heard. Neither of the British ships reported any incident during this period but Paul Bootherstone recalls that when the Arrow's towed torpedo decoy was retrieved later it was found to be badly damaged". The Royal Navy and Falklands War, pp. 156-157, David Brown, Pen and Sword, 1987

- França oferece "Foudre" à Argentina Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Armada Argentina. ":: ARMADA ARGENTINA ::". Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- "Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe – Las crisis de Guatemala (1954) y Haití (1991-1994):". Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- mindef: El comienzo en agosto próximo en los Astilleros Tandanor (en Buenos Aires) de la construcción primera de las cuatro Patrulleras Oceánicas Multipropósito, cuya ingeniería básica fue adquirida a la industria chilena. Archived 2010-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Argentina takes ship dispute with Ghana to UN court". BBC News. 14 November 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013.

- "Ghana told to free Argentine ship Libertad by UN court". BBC News. 15 December 2012. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.

- "Order: The "ARA Libertad" Case" (PDF). International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Hamburg. 15 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Daniel Schweimler (10 January 2013). "Argentine naval frigate returns home". Financial Times.

- "Argentine navy short on spares and resources for training and maintenance". MercoPress. 22 November 2012. Archived from the original on 28 December 2012.

- "Argentine destroyer that led war against Britain sinks, a symbol of decay for once-proud navy". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Atlasur VIII Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "Submarino ARA San Juan: la Armada dio por finalizado el operativo de rescate y ya no busca sobrevivientes". lanacion.com.ar. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Redacción (18 July 2019). "Informe Final del Congreso: Macri y Aguad son responsables del hundimiento del ARA San Juan". elAgora.digital (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Brazil will supply Argentina with German built submarines in need of repair". MercoPress. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- https://baexpats.org/threads/brazil-to-give-4-submarines-to-argentina.41317/

- https://www.naval-technology.com/projects/ssk-tupi/

- https://www.naval-technology.com/news/argentinas-p-3c-orion-aircraft-support-package-sale-approved-by-us/

- https://www.infodefensa.com/latam/2020/08/10/noticia-ministerio-defensa-argentino-delinea-reequipamiento-armada-argentina.html

- https://elagora.digital/mesa-interministerial-pesca-ilegal/

- https://www.infodefensa.com/latam/2020/08/10/noticia-ministerio-defensa-argentino-delinea-reequipamiento-armada-argentina.html

- "Operaciones para el mantenimiento de la paz" (in Spanish). Argentina.gob.ar. 14 July 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Nuevo contingente de Cascos Azules parte hacia Chipre" (in Spanish). Gaceta Marinera. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

Sources

- Ehlers, Hartmut (2004). "The Paraguayan Navy: Past and Present, Part II". Warship International. XLI (2): 173–206. ISSN 0043-0374.

Further reading

- Guia de los buques de la Armada Argentina 2005–2006. Ignacio Amendolara Bourdette, ISBN 987-43-9400-5, Editor n/a. (Spanish/English text)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Argentine Navy. |

- (in Spanish) Official website

- (in Spanish) Videos BravoZulu Official news programme

- (in Spanish) Unofficial website

- (in Spanish) Organization and equipment