Colonization of Antarctica

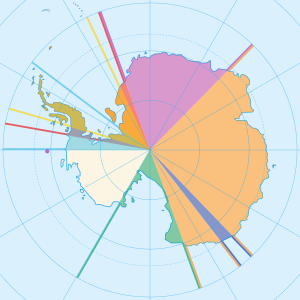

Colonization of Antarctica refers to having humans, including families, living permanently on the continent of Antarctica. Currently, the continent hosts only a temporary transient population of scientists and support staff. Antarctica is the only continent on Earth without indigenous human inhabitants.

At present scientists and staff from 30 countries live on about 70 bases (40 year-round and 30 summer-only), with an approximate population of 4,000 in summer and 1,000 in winter. There have been at least eleven human births in Antarctica, starting with one in 1978 at an Argentine base, with seven more at that base and three at a Chilean base.

Past colonization speculation

An idea common in the 1950s was to have Antarctic cities enclosed under glass domes, which would make colonization of the continent possible. Power and temperature regulation of the domes would come from atomic driven generators outside of these domes. A light source at the top of the central tower had been proposed as an artificial sun during the dark months in Antarctica. This scenario would also include regular trans-Antarctic flights as well as mining towns which were dug into Antarctica's ice caps above the shafts down to mineral bearing mountains; however, there are problems with the idea of having an atomic driven generator giving the power and temperature regulation. The atomic reactor at McMurdo Station became a pollution hazard and hence was closed down long ago.[1]

The Antarctic Treaty System, a series of international agreements, presently limit activities on Antarctica. It would need to be modified or abandoned before large-scale colonization could legally occur, in particular with respect to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. On the other hand, it is the very impracticability of permanent colonization that has contributed to the failure of any of the territorial claims to receive international recognition.[2]

Domed cities

Buckminster Fuller, the developer of the geodesic dome, had raised the possibility of Antarctic domed cities that would allow a controlled climate and buildings erected under the dome.[3] His first specific published proposal for a domed city in 1965 discussed the Antarctic as a likely first location for such a project.[4] The second base at Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station (operated 1975-2003) resembles a reduced version of this idea; it is large enough to cover only a few scientific buildings.

In 1971, a team led by German architect Frei Otto made a feasibility study for an air-supported city dome two kilometers across that could house 40,000 residents.[5] Some authors have recently tried to update the idea.[6]

Future conditions

Though the environment of Antarctica is too harsh for permanent human settlement to be worthwhile, conditions may become better in the future. It has been suggested that, as a result of long-term effects of global warming, the beginning of the 22nd century will see parts of West Antarctica experiencing similar climate conditions to those found today in Alaska and Northern Scandinavia.[7] Even farming and crop growing could be possible in some of the most northerly areas of Antarctica.

It is suggested that plants and fungi find a favorable environment around the Antarctica's volcanoes to grow, a hint as to where the first agricultural efforts could be led.[8] There are about 110 native species of moss in Antarctica, and two angiosperms (Deschampsia antarctica and Colobanthus quitensis). It is believed those native species will disappear with warmer weather and the arrival of stronger species. Humans are responsible for the introduction to 200 to 300 outside species on the continent.[9]

Recently scientific surveys of an area near the South Pole have revealed high geothermal heat seeping up to the surface from below.[10][11]

Births in Antarctica

Emilio Marcos Palma (born January 7, 1978) is an Argentine citizen who is the first person known to be born on the continent of Antarctica. He was born in Fortín Sargento Cabral at the Esperanza Base near the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and weighed 3.4 kg (7 lb 8 oz). Since his birth, about ten others have been born on the continent.

See also

- Antarctic territorial claims

- List of Antarctic field camps

- Research stations in Antarctica

- Antarctica: The Battle for the Seventh Continent

References

- Elzinga, Aant (1993). "Antarctica: The Construction of a Continent by and For Science". In Elisabeth Crawford, Terry Shinn, & Sverker Sörlin (Eds.), Denationalizing Science: The Contexts of International Scientific Practice, pp. 73-106. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Joyner, Christopher C. (1992). Antarctica and the Law of the Sea, p. 49. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-1823-4.

- Marks, Robert W. (Aug. 23, 1959). "The Breakthrough of Buckminster Fuller". The New York Times, pp. SM14, SM15, SM42, SM44.

- Fuller, Buckminster (Sep. 26, 1965). "The Case for Domed Cities Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine". St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

- Walker, Derek (1998). Happold: The Confidence to Build, p. 63. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-419-24070-5.

- Alexander Bolonkin and Cathcart, Richard B. (May 2007). "Inflatable ‘Evergreen’ dome settlements for Earth’s Polar Regions". Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 9 (2), 125–132.

- How to survive the coming century, NewScientist .

- "An ice age can make your home pretty inhospitable..." Science.org.au. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Tom Hart (15 September 2015). "Polar invasion: how plants and animals would colonise an ice-free Antarctica". Theconversation.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Dinar, Athena. "Discovery of high geothermal heat at South Pole". www.phys.org/news. British Antarctic Survey. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- Fox, Douglas. "High Heat Measured under Antarctica Could Support Substantial Life". www.scientificamerican.com/article. Scientific American. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

.svg.png)