Elephant Island

Elephant Island is an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands, in the Southern Ocean. The island is situated 245 kilometres (152 miles) north-northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, 1,253 kilometres (779 miles) west-southwest of South Georgia, 935 kilometres (581 miles) south of the Falkland Islands, and 885 kilometres (550 miles) southeast of Cape Horn. It is within the Antarctic claims of Argentina, Chile and the United Kingdom.

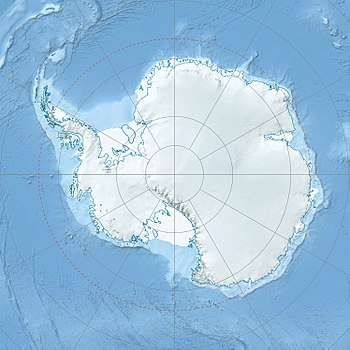

Elephant Location in the South Shetland Islands  Elephant Location in Antarctica | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Antarctica |

| Coordinates | 61°08′S 55°07′W |

| Archipelago | South Shetland Islands |

| Area | 558 km2 (215 sq mi) |

| Length | 47 km (29.2 mi) |

| Width | 27 km (16.8 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 973 m (3,192 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Pendragon |

| Administration | |

| Administered under the Antarctic Treaty | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Uninhabited |

The Brazilian Antarctic Program maintains a shelter on the island, Goeldi, supporting the work of up to six researchers each during the summer,[1] and formerly had another (Wiltgen), which was dismantled in the summers of 1997 and 1998.

Toponym

Elephant Island's name is attributed to both its elephant head-like appearance and the sighting of elephant seals by Captain George Powell in 1821, one of the earliest sightings.

Geography

.jpg)

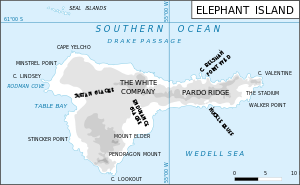

The island is oriented approximately east–west, with a maximum elevation of 853 m (2,799 ft) at Pardo Ridge. The weather is normally foggy with much snow, and winds can reach 160 km/h (100 mph).

Significant named features are Cape Yelcho, Cape Valentine and Cape Lookout at the northeastern and southern extremes, and Point Wild, a spit on the north coast. The Endurance Glacier is the main discharge glacier.

Geology

Elephant Island is part of the Scotia metamorphic complex, which was created by Cretaceous sea floor sediments being scraped off and metamorphosed at the Scotia subduction zone. The resulting rocks are phyllites, blueschists and greenschists typical of an accretionary wedge, with increased metamorphism from northeast to southwest. These rocks are at the surface here because of uplift along the Shackleton Fault Zone where it meets the South Scotia Ridge. This complex is very similar in age and rock types to those of coastal California, including Catalina Island and the Big Sur coast.[2]

Flora and fauna

.jpg)

The island supports no significant flora or native fauna, although migratory gentoo penguins and seals may be found, and chinstrap penguins nest in season. A lack of safe anchorage has prevented any permanent human settlement, despite the island being well placed to support scientific, fishing and whaling activities. Due to slow recoveries and illegal whaling by the Soviet Union with support from Japan, numbers of southern right whales visiting Elephant island are still at low levels.

History

First Russian Antarctic expedition

The First Russian Antarctic expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev on the 985-ton sloop-of-war Vostok ("East") and the 530-ton support vessel Mirny ("Peaceful") discovered Elephant Island on 29 January 1821 and named it Остров Мордвинова ("Mordvinov Island") in honour of Admiral Mordvinov.

Endurance expedition

The island was the desolate refuge of the British explorer Ernest Shackleton and his crew in 1916 following the loss of their ship Endurance in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea. The crew of 28 reached Cape Valentine on Elephant Island after months spent drifting on ice floes and a harrowing crossing of the open ocean in small lifeboats.[3] After camping at Cape Valentine for two nights, Shackleton and his crew moved 11 km (7 mi) west to a small, rocky spit at the terminus of a glacier, which offered better protection from rockfalls and from the sea, and which they called Point Wild.

Realizing that there was no chance of passive rescue, Shackleton decided to sail to South Georgia, where he knew there were several whaling stations. Shackleton sailed with Tom Crean, Frank Worsley, Harry "Chippy" McNish, Tim McCarthy, and John Vincent on an 1,300 km (800 mi) voyage in the open lifeboat James Caird beginning on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, and arriving at South Georgia 16 days later. His second-in-command, Frank Wild, was left in charge of the remaining party on Elephant Island, waiting for Shackleton's return with a rescue ship.[4]

There was much work for the stranded men. Because the island had no natural source of shelter, they constructed a shack and wind blocks from their remaining two lifeboats and pieces of canvas tents. Blubber lamps were used for lighting. They hunted for penguins and seals, neither of which were plentiful in autumn or winter. Shackleton instructed Wild to depart with the crew for Deception Island if he did not return to rescue them by the beginning of summer, but after four and a half months, on August 30, 1916, the artist George Marston spotted a ship. The ship, with Shackleton on board, was the tug Yelcho, from Punta Arenas, Chile, commanded by Luis Pardo, which rescued all the men who had set out on the original expedition.

Joint Services Expeditions 1970–71

A Joint Services Expedition led by Commander Malcolm Burley was dropped off on Elephant Island by HMS Endurance. The party then spent six months carrying out a survey of the island and other scientific research for the British Antarctic Survey and climbing some of the peaks on the island.[5] The expedition visited Point Wild but found no trace of the Endurance expedition; it did, however, find the wreckage of a large sailing vessel, likely the remains of the schooner Charles Shearer from Stonington, New London, Connecticut, under Captain William Henry Appelman. The expedition also landed on and climbed the highest peak on nearby Clarence Island.[6][7]

Historic sites

Point Wild contains the Endurance Memorial Site, an Antarctic Historic Site (HSM 53), with a bust of Captain Pardo and several plaques. Hampson Cove on the southwest coast of the island, including the foreshore and intertidal area, contains the wreckage of a large wooden sailing vessel; it has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 74), following a proposal by the United Kingdom to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[8][7]

Maps

- British Antarctic Territory. Scale 1:200000 topographic map. DOS 610 Series, Sheet W 61 54. Directorate of Overseas Surveys, Tolworth, UK, 1972.

- South Shetland Islands: Elephant, Clarence and Gibbs Islands. Scale 1:220000 topographic map. UK Antarctic Place-names Committee, 2009.

- Antarctic Digital Database (ADD). Scale 1:250000 topographic map of Antarctica. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). Since 1993, regularly upgraded and updated.

See also

- Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica

- The Cornet

- List of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands

- Prince Charles Strait

- Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research

- Territorial claims in Antarctica

References

- "The Brazilian Antarctic Program". Vivabrazil.com. 1984-02-06. Retrieved 2011-04-22.

- Joseph Holliday, Geology Professor, El Camino College

- Shackleton, Earnest. South. The Endurance Expedition. Penguin Books, London, 1999, p. 157.

- "Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition". Amnh.org. Retrieved 2011-04-22.

- M. Burley. Joint Services Expedition to Elephant Island. Geographical Journal, 1972

- C.H. Agnew of Lochnaw. Elephant Island. Alpine Journal, 1972. pp. 204-210

- Historic Sites and Monuments: Sailing Vessel Wreckage, Southwest Coast of Elephant Island, South Shetland Islands. Working Paper submitted by the United Kingdom. SATCM XII. The Hague, 2000

- "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2012)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2012. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elephant Island. |

- Antarctica Sydney: Reader's Digest, 1985.

- Child, Jack Antarctica and South American Geopolitics: Frozen Lebensraum New York: Praeger Publishers, 1988.

- Furse, Chris Elephant Island - An Antarctic Expedition Shrewsbury: Anthony Nelson Ltd, 7 St John's Hill, Shrewsbury SY1 1JE, England, ISBN 0-904614-02-6.

- Mericq, Luis Antarctica: Chile's Claim. Washington: National Defense University, 1987.

- Pinochet de la Barra, Oscar La Antarctica Chilena Santiago: Editorial Andrés Bello, 1976.

- Stewart, Andrew Antarctica: An Encyclopedia London: McFarland and Co., 1990 (2 volumes).

- Worsley, Frank Shackleton's Boat Journey W.W. Norton & Co., 1933.

.svg.png)