Karachi

Karachi (Urdu: کراچی; Sindhi: ڪراچي; ALA-LC: Karācī, IPA: [kəˈraːtʃi] (![]()

Karachi کراچی | |

|---|---|

_Head_Office_Building_Karachi.jpg) Clockwise from top: Mazar-e-Quaid, Hawke's Bay Beach, Frere Hall, Karachi Port Trust Building, Mohatta Palace, Port of Karachi | |

| Nickname(s): | |

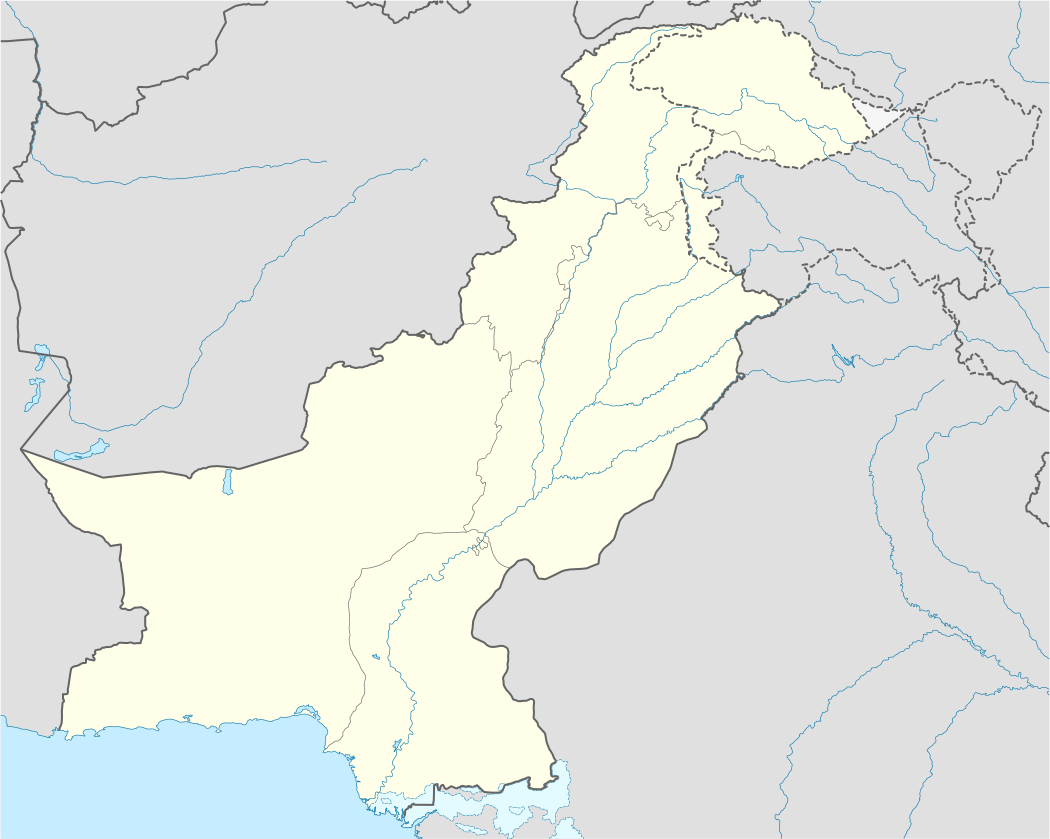

Karachi Location in Pakistan  Karachi Karachi (Pakistan)  Karachi Karachi (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 24°51′36″N 67°0′36″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Division | Karachi |

| Metropolitan council | 1880 |

| City council | City Complex, Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town |

| Districts[6] | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Metropolitan Corporation |

| • Body | Government of Karachi |

| • Mayor | Waseem Akhtar (MQM-P) |

| • Deputy mayor | Arshad Hassan (MQM-P) |

| • Commissioner | Iftikhar Ali Shallwani[8] |

| Area | |

| • City | 3,780 km2 (1,460 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 14,910,352 |

| • Rank |

|

| • Density | 3,900/km2 (10,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 16,051,521 |

| Demonym(s) | Karachiite |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PST) |

| Postal codes | 74XXX – 75XXX |

| Dialing code | +9221-XXXX XXX |

| GDP/PPP | $114 billion (2014)[13][14] |

| HDI (2017) | |

| Website | www |

Though the Karachi region has been inhabited for millennia,[26] the city was founded as the fortified village of Kolachi in 1729.[27][28] The settlement drastically increased in importance with the arrival of British East India Company in the mid 19th century. The British embarked on major works to transform the city into a major seaport, and connected it with their extensive railway network.[28] By the time of the Partition of British India, the city was the largest in Sindh with an estimated population of 400,000.[22] Following the independence of Pakistan, the city's population increased dramatically with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees from India.[29] The city experienced rapid economic growth following independence, attracting migrants from throughout Pakistan and South Asia.[30] According to the 2017 census, Karachi's total population was 16,051,521 and its urban population was 14.9 million. Karachi is one of the world's fastest growing cities,[31] and has communities representing almost every ethnic group in Pakistan. Karachi is home to more than two million Bangladeshi immigrants, a million Afghan refugees, and up to 400,000 Rohingyas from Myanmar.[32][33][34]

Karachi is now Pakistan's premier industrial and financial centre. The city has a formal economy estimated to be worth $114 billion as of 2014 which is the largest in Pakistan.[35][13] Karachi collects more than a third of Pakistan's tax revenue,[36] and generates approximately 20% of Pakistan's GDP.[37][38] Approximately 30% of Pakistani industrial output is from Karachi,[39] while Karachi's ports handle approximately 95% of Pakistan's foreign trade.[40] Approximately 90% of the multinational corporations operating in Pakistan are headquartered in Karachi.[40] Karachi is considered to be Pakistan's fashion capital,[41][42] and has hosted the annual Karachi Fashion Week since 2009.[43][44]

Known as the "City of Lights" in the 1960s and 1970s for its vibrant nightlife,[45] Karachi was beset by sharp ethnic, sectarian, and political conflict in the 1980s with the arrival of weaponry during the Soviet–Afghan War.[46] The city had become well known for its high rates of violent crime, but recorded crimes sharply decreased following a controversial crackdown operation against criminals, the MQM political party, and Islamist militants initiated in 2013 by the Pakistan Rangers.[47] As a result of the operation, Karachi went from being ranked the world's 6th most dangerous city for crime in 2014, to 93rd by early 2020.[48]

Etymology

Modern Karachi was reputedly founded in 1729 as the settlement of Kolachi-jo-Goth.[27] The new settlement is said to have been named in honour of Mai Kolachi, whose son is said to have slain a man-eating crocodile in the village after his elder brothers had already been killed by it.[27] The name Karachee, a shortened and corrupted version the original name Kolachi-jo-Goth, was used for the first time in a Dutch report from 1742 about a shipwreck near the settlement.[49][50]

History

Early history

The region around Karachi has been the site of human habitation for millennia. Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic sites have been excavated in the Mulri Hills along Karachi's northern outskirts. These earliest inhabitants are believed to have been hunter-gatherers, with ancient flint tools discovered at several sites.

The expansive Karachi region is believed to have been known to the ancient Greeks, and may have been the site of Barbarikon, an ancient seaport which was located at the nearby mouth of the Indus River.[51][52][53][54] Karachi may also have been referred to as Ramya in ancient Greek texts.[55]

The ancient site of Krokola, a natural harbor west of the Indus where Alexander the Great sailed his a fleet for Achaemenid Assyria, may have been located near the mouth of Karachi's Malir River,[56][57][58] though some believe it was located near Gizri.[59][60] No other natural harbor exists near the mouth of the Indus that could accommodate a large fleet.[61] Nearchus, who commanded Alexander's naval fleet, also mentioned a hilly island by the name of Morontobara and an adjacent flat island named Bibakta, which colonial historians identified as Karachi's Manora Point and Kiamari (or Clifton), respectively, based on Greek descriptions.[62][63][64] Both areas were island until well into the colonial era, when silting in led to them being connected to the mainland.[65]

In 711 CE, Muhammad bin Qasim conquered the Sindh and Indus Valley and the port of Debal, from where he launched his forces further into the Indus Valley in 712.[66] Some have identified the port with Karachi, though some argue the location was somewhere between Karachi and the nearby city of Thatta.[67][68]

Under Mirza Ghazi Beg, the Mughal administrator of Sindh, the development of coastal Sindh and the Indus River Delta was encouraged. Under his rule, fortifications in the region acted as a bulwark against Portuguese incursions into Sindh. In 1553–54, Ottoman admiral Seydi Ali Reis, mentioned a small port along the Sindh coast by the name of Kaurashi which may have been Karachi.[69][70][71] The Chaukhandi tombs in Karachi's modern suburbs were built around this time between the 15th and 18th centuries.

Kolachi settlement

19th century Karachi historian Seth Naomal Hotchand recorded that a small settlement of 20–25 huts existed along the Karachi Harbour that was known as Dibro, which was situated along a pool of water known as Kolachi-jo-Kun.[72] In 1725, a band of Balochi settlers from Makran and Kalat had settled in the hamlet after fleeing droughts and tribal feuds.[73]

A new settlement was built in 1729 at the site of Dibro, which came to be known as Kolachi-jo-Goth ("The village of Kolachi").[27] The new settlement is said to have been named in honour of Mai Kolachi, a resident of the old settlement whose son is said to have slain a man-eating crocodile.[27] Kolachi was about 40 hectares in size, with some smaller fishing villages scattered in its vicinity.[74] The founders of the new fortified settlement were Sindhi Baniyas,[73] and are said to arrived from the nearby town of Kharak Bandar after the harbour there silted in 1728 after heavy rains.[75] Kolachi was fortified, and defended with cannons imported from Muscat, Oman. Under the Talpurs, the Rah-i-Bandar road was built to connect the city's port to the caravan terminals.[76] This road would eventually be further developed by the British into Bandar Road, which was renamed Muhammad Ali Jinnah Road.[77][78]

The name Karachee was used for the first time in a Dutch document from 1742, in which a merchant ship de Ridderkerk is shipwrecked near the settlement.[49][50] In 1770s, Karachi came under the control of the Khan of Kalat, which attracted a second wave of Balochi settlers.[73] In 1795, Karachi was annexed by the Talpurs, triggering a third wave of Balochi settlers who arrived from interior Sindh and southern Punjab.[73] The Talpurs built the Manora Fort in 1797,[79][80] which was used to protect Karachi's Harbor from al-Qasimi pirates.[81]

In 1799 or 1800, the founder of the Talpur dynasty, Mir Fateh Ali Khan, allowed the East India Company under Nathan Crow to establish a trading post in Karachi.[82] He was allowed to build a house for himself in Karachi at that time, but by 1802 was ordered to leave the city.[83] The city continued to be ruled by the Talpurs until it was occupied by forces under the command of John Keane in February 1839.[84]

British control

_Head_Office_at_M.A_Jinnah_Road_-_Photo_By_Aliraza_Khatri.jpg)

The British East India Company captured Karachi on 3 February 1839 after HMS Wellesley opened fire and quickly destroyed Manora Fort, which guarded Karachi Harbour at Manora Point.[85] Karachi's population at the time was an estimated 8,000 to 14,000,[86] and was confined to the walled city in Mithadar, with suburbs in what is now the Serai Quarter.[87] British troops, known as the "Company Bahadur" established a camp to the east of the captured city, which became the precursor to the modern Karachi Cantonment. The British further developed the Karachi Cantonment as a military garrison to aid the British war effort in the First Anglo-Afghan War.[88]

Sindh's capital was shifted from Hyderabad to Karachi in 1840 until 1843, when Karachi was annexed to the British Empire after Major General Charles James Napier captured the rest of Sindh following his victory against the Talpurs at the Battle of Miani. Following the 1843 annexation, the entire province was amalgamated into the Bombay Presidency for the next 93 years. A few years later in 1846, Karachi suffered a large cholera outbreak, which led to the establishment of the Karachi Cholera Board (predecessor to the city's civic government).[89]

The city grew under the administration of its new Commissioner, Henry Bartle Edward Frere, who was appointed in 1850s. Karachi was recognized for its strategic importance, prompting the British to establish the Port of Karachi in 1854. Karachi rapidly became a transportation hub for British India owing to newly built port and rail infrastructure, as well as the increase in agricultural exports from the opening of productive tracts of newly irrigated land in Punjab and interior Sindh.[90] By 1856, the value of goods traded through Karachi reached ₤855,103, leading to the establishment of merchant offices and warehouses.[91] The population in 1856 is estimated to have been 57,000.[92] During the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, the 21st Native Infantry, then stationed in Karachi, mutinied and declared allegiance to rebel forces in September 1857, though the British were able to quickly defeat the rebels and reassert control over the city.

Following the Rebellion, British colonial administrators continued to develop the city's infrastructure, but continued to neglect localities like Lyari, which was home to the city's original population of Sindhi fishermen and Balochi nomads.[93] At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Karachi's port became an important cotton-exporting port,[92] with Indus Steam Flotilla and Orient Inland Steam Navigation Company established to transport cotton from interior Sindh to Karachi's port, and onwards to textile mills in England.[94] With increased economic opportunities, economic migrants from several ethnicities and religions, including Anglo-British, Parsis, Marathis, and Goan Christians, among others, established themselves in Karachi,[92] with many setting-up businesses in the new commercial district of Saddar. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, was born in Karachi's Wazir Mansion in 1876 to such migrants from Gujarat. Public building works were undertaken at this time in Gothic and Indo-Saracenic styles, including the construction of Frere Hall in 1865 and the later Empress Market in 1889.

With the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, Karachi's position as a major port increased even further.[92] In 1878, the British Raj connected Karachi with the network of British India's vast railway system. In 1887, Karachi Port underwent radical improvements with connection to the railways, along with expansion and dredging of the port, and construction of a breakwater.[92] Karachi's first synagogue was established in 1893.[95] By 1899, Karachi had become the largest wheat-exporting port in the East.[96] In 1901, Karachi's population was 117,000 with a further 109,000 included in the Municipal area.[92]

Under the British, the city's municipal government was established. Known as the Father of Modern Karachi, mayor Seth Harchandrai Vishandas led the municipal government to improve sanitary conditions in the Old City, as well as major infrastructure works in the New Town after his election in 1911.[2] in 1914, Karachi had become the largest wheat-exporting port of the entire British Empire,[97] after large irrigation works in interior Sindh were initiated to increase wheat and cotton yields.[92] By 1924, the Drigh Road Aerodrome was established,[92] now the Faisal Air Force Base.

Karachi's increasing importance as a cosmopolitan transportation hub lead to the influence of non-Sindhis in Sindh's administration. Half the city was born outside of Karachi by as early as 1921.[98] Native Sindhis were upset by this influence,[92] and so 1936, Sindh was re-established as a province separate from the Bombay Presidency with Karachi was once again made capital of Sindh. In 1941, the population of the city had risen to 387,000.[92]

Post-independence

At the dawn of independence following the success of the Pakistan Movement in 1947, Karachi was Sindh's largest city with a population of over 400,000.[22] Partition resulted in the exodus of much of the city's Hindu population, though Karachi, like most of Sindh, remained relatively peaceful compared to cities in Punjab.[99] Riots erupted on 6 January 1948, after which most of Sindh's Hindu population left for India,[99] with assistance of the Indian government.[100]

Karachi became the focus for the resettlement of middle-class Muslim Muhajir refugees who fled India, with 470,000 refugees in Karachi by May 1948,[101] leading to a drastic alteration of the city's demography. In 1941, Muslims were 42% of Karachi's population, but by 1951 made up 96% of the city's population.[98] The city's population had tripled between 1941 and 1951.[98] Urdu replaced Sindhi as Karachi's most widely spoken language; Sindhi was the mother tongue of 51% of Karachi in 1941, but only 8.5% in 1951, while Urdu grew to become the mother tongue of 51% of Karachi's population.[98] 100,000 Muhajir refugees arrived annually in Karachi until 1952.[98]

Karachi was selected as the first capital of Pakistan, and was administered as a federal district separate from Sindh beginning in 1948,[101] until the capital was shifted to Rawalpindi in 1958.[102] While foreign embassies shifted away from Karachi, the city is host to numerous consulates and honorary consulates.[103] Between 1958 and 1970, Karachi's role as capital of Sindh was ceased due to the One Unit programme enacted by President Iskander Mirza.[2]

Karachi of the 1960s was regarded as an economic role model around the world, with Seoul, South Korea, borrowing from the city's second "Five-Year Plan".[104][105] Several examples of Modernist architect were built in Karachi during this period, including the Mazar-e-Quaid mausoleum, the distinct Masjid-e-Tooba, and the Habib Bank Plaza (the tallest building in all of South Asia at the time). The city's population by 1961 had grown 369% compared to 1941.[98] By the mid 1960s, Karachi began to attract large numbers of Pashtun and Punjabis from northern Pakistan.[98]

The 1970s saw a construction boom funded by remittances and investments from the Gulf States, and the appearance of apartment buildings in the city.[106] Real-estate prices soared during this period, leading to a worsening housing crisis.[107] The period also saw labour unrest in Karachi's industrial estates beginning in 1970 that were violently repressed by the government of President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto from 1972 onwards.[108] To appease conservative forces, Bhutto banned alcohol in Pakistan, and cracked-down of Karachi's discotheques and cabarets - leading to the closure of Karachi's once-lively nightlife.[109] The city's art scene was further repressed during the rule of dictator General Zia-ul-Haq.[109] Zia's Islamization policies lead the Westernized upper-middle classes of Karachi to largely withdraw from the public sphere, and instead form their own social venues that became inaccessible to the poor.[109]

The 1980s and 1990s saw an influx of almost one million Afghan refugees into Karachi fleeing the Soviet–Afghan War;[98] who were in turn followed in smaller numbers by refugees escaping from post-revolution Iran.[110] At this time, Karachi was also rocked by political conflict, while crime rates drastically increased with the arrival of weaponry from the War in Afghanistan.[46] Conflict between the MQM party, and ethnic Sindhis, Pashtuns, and Punjabis was sharp.[111] The party and its vast network of supporters were targeted by Pakistani security forces as part of the controversial Operation Clean-up in 1992 – an effort to restore peace in the city that lasted until 1994.[112] Anti-Hindu riots also broke out in Karachi in 1992 in retaliation for the demolition of the Babri Mosque in India by a group of Hindu nationalists earlier that year.[113]

The 2010s saw another influx of hundreds of thousands of Pashtun refugees fleeing conflict in North-West Pakistan and the 2010 Pakistan floods.[98] By this point Karachi had become widely known for its high rates of violent crime, usually in relation to criminal activity, gang-warfare, sectarian violence, and extrajudicial killings.[93] Recorded crimes sharply decreased following a controversial crackdown operation against criminals, the MQM party, and Islamist militants initiated in 2013 by the Pakistan Rangers.[47] As a result of the operation, Karachi went from being ranked the world's 6th most dangerous city for crime in 2014, to 93rd by early 2020.[48]

Geography

Karachi is located on the coastline of Sindh province in southern Pakistan, along the Karachi Harbour, a natural harbour on the Arabian Sea. Karachi is built on a coastal plain with scattered rocky outcroppings, hills and marshlands. Mangrove forests grow in the brackish waters around the Karachi Harbour, and farther southeast towards the expansive Indus River Delta. West of Karachi city is the Cape Monze, locally known as Ras Muari, which is an area characterised by sea cliffs, rocky sandstone promontories and undeveloped beaches.

Within the city of Karachi are two small ranges: the Khasa Hills and Mulri Hills, which lie in the northwest and act as a barrier between North Nazimabad and Orangi.[114] Karachi's hills are barren and are part of the larger Kirthar Range, and have a maximum elevation of 528 metres (1,732 feet).

Between the hills are wide coastal plains interspersed with dry river beds and water channels. Karachi has developed around the Malir River and Lyari Rivers, with the Lyari shore being the site of the settlement for Kolachi. To the west of Karachi lies the Indus River flood plain.[115]

Climate

Karachi has a hot desert climate (Köppen: BWh) dominated by a long "Summer Season" while moderated by oceanic influence from the Arabian Sea. The city has low annual average precipitation levels (approx. 250 mm (10 in) per annum), the bulk of which occurs during the July–August monsoon season. While the summers are hot and humid, cool sea breezes typically provide relief during hot summer months, though Karachi is prone to deadly heat waves,[116] though a text message-based early warning system is now in place which helped prevent any fatalities during an unusually strong heatwave in October 2017.[117] The winter climate is dry and lasts between December and February. It is dry and pleasant relative to the warm hot season, which starts in March and lasts until monsoons arrive in June. Proximity to the sea maintains humidity levels at near-constant levels year-round.

The city's highest monthly rainfall, 429.3 mm (16.90 in), occurred in July 1967.[118] The city's highest rainfall in 24 hours occurred on 7 August 1953, when about 278.1 millimetres (10.95 in) of rain lashed the city, resulting in major flooding.[119] Karachi's highest recorded temperature is 48 °C (118 °F) which was recorded on 9 May 1938,[120] and the lowest is 0 °C (32 °F) recorded on 21 January 1934.[118]

| Climate data for Karachi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

36.5 (97.7) |

42.2 (108.0) |

44.0 (111.2) |

46.0 (114.8) |

47.0 (116.6) |

41.1 (106.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

42.2 (108.0) |

42.6 (108.7) |

38.5 (101.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

47.0 (116.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.2 (82.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.7 (94.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

32.1 (89.8) |

33.2 (91.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

32.4 (90.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

21.2 (70.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

1.3 (34.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8.4 (0.33) |

7.4 (0.29) |

5.3 (0.21) |

3.0 (0.12) |

0.1 (0.00) |

10.8 (0.43) |

60.0 (2.36) |

60.9 (2.40) |

11.0 (0.43) |

2.6 (0.10) |

0.4 (0.02) |

4.8 (0.19) |

174.7 (6.88) |

| Average precipitation days | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 8.0 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 16.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 269.7 | 251.4 | 272.8 | 276 | 297.6 | 231 | 155 | 148.8 | 219 | 282.1 | 273 | 272.8 | 2,949.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.7 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 5 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 8.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 81 | 79 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 56 | 37 | 37 | 59 | 78 | 83 | 83 | 68 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 10 |

| Source 1: PMD (1991–2020)[121] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[122] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

The city first developed around the Karachi Harbour, and owes much of its growth to its role as a seaport at the end of the 18th century,[123] contrasted with Pakistan's millennia-old cities such as Lahore, Multan, and Peshawar. Karachi's Mithadar neighbourhood represents the extent of Kolachi prior to British rule.

British Karachi was divided between the "New Town" and the "Old Town", with British investments focused primarily in the New Town.[88] The Old Town was a largely unplanned neighbourhood which housed most of the city's indigenous residents, and had no access to sewerage systems, electricity, and water.[88] The New Town was subdivided into residential, commercial, and military areas.[88] Given the strategic value of the city, the British developed the Karachi Cantonment as a military garrison in the New Town to aid the British war effort in the First Anglo-Afghan War.[88] The city's development was largely confined to the area north of the Chinna Creek prior to independence, although the seaside area of Clifton was also developed as a posh locale under the British, and its large bungalows and estates remain some of the city's most desirable properties. The aforementioned historic areas form the oldest portions of Karachi, and contain its most important monuments and government buildings, with the I. I. Chundrigar Road being home to most of Pakistan's banks, including the Habib Bank Plaza which was Pakistan's tallest building from 1963 until the early 2000s.[2] Situated on a coastal plain northwest of Karachi's historic core lies the sprawling district of Orangi. North of the historic core is the largely middle-class district of Nazimabad, and upper-middle class North Nazimabad, which were developed in the 1950s. To the east of the historic core is the area known as Defence, an expansive upscale suburb developed and administered by the Pakistan Army. Karachi's coastal plains along the Arabian Sea south of Clifton were also developed much later as part of the greater Defence Housing Authority project. Karachi's city limits also include several islands, including Baba and Bhit Islands, Oyster Rocks, and Manora, a former island which is now connected to the mainland by a thin 12-kilometre long shoal known as Sandspit. The city has been described as one divided into sections for those able to afford to live in planned localities with access to urban amenities, and those who live in unplanned communities with inadequate access to such services.[124] Up to 60% of Karachi's residents live in such unplanned communities.[124]

Economy

At a height of 300 metres (980 ft), Bahria Icon Tower is the tallest skyscraper in Pakistan and second tallest in South Asia.

At a height of 300 metres (980 ft), Bahria Icon Tower is the tallest skyscraper in Pakistan and second tallest in South Asia. Lucky One Mall is the largest shopping mall in Pakistan as well as in South Asia with an area of about 3.4 million square feet.[125][126][127]

Lucky One Mall is the largest shopping mall in Pakistan as well as in South Asia with an area of about 3.4 million square feet.[125][126][127] The city's colonial-era core has traditionally a high density of small businesses.

The city's colonial-era core has traditionally a high density of small businesses. Karachi's downtown is centered on I. I. Chundrigar Road.

Karachi's downtown is centered on I. I. Chundrigar Road.

Karachi is Pakistan's financial and commercial capital.[128] Since Pakistan's independence, Karachi has been the centre of the nation's economy, and remain's Pakistan's largest urban economy despite the economic stagnation caused by sociopolitical unrest during the late 1980s and 1990s. The city forms the centre of an economic corridor stretching from Karachi to nearby Hyderabad, and Thatta.[129]

As of 2014, Karachi had an estimated GDP (PPP) of $114 billion.[14][13] As of 2008, the city's gross domestic product (GDP) by purchasing power parity (PPP) was estimated at $78 billion with a projected average growth rate of 5.5 percent.[14][13] Karachi contributes the bulk of Sindh's gross domestic product.[130][131][132][133] and accounts for approximately 20% of the total GDP of Pakistan.[37][38] The city has a large informal economy which is not typically reflected in GDP estimates.[134] The informal economy may constitute up to 36% of Pakistan's total economy, versus 22% of India's economy, and 13% of the Chinese economy.[135] The informal sector employs up to 70% of the city's workforce.[136] In 2018 The Global Metro Monitor Report ranked Karachi's economy as the best performing metropolitan economy in Pakistan.[137]

Today along with Pakistan's continued economic expansion Karachi is now ranked third in the world for consumer expenditure growth with its market anticipated to increase by 6.6% in real terms in 2018[138] It is also ranked among the top cities in the world by anticipated increase of number of households (1.3 million households) with annual income above $20,000 dollars measured at PPP exchange rates by year 2025.[139] The Global FDI Intelligence Report 2017/2018 published by Financial Times ranks Karachi amongst the top 10 Asia pacific cities of the future for FDI strategy.[140]

Finance and banking

Most of Pakistan's public and private banks are headquartered on Karachi's I. I. Chundrigar Road, which is known as "Pakistan's Wall Street",[2] with a large percentage of the cashflow in the Pakistani economy taking place on I. I. Chundrigar Road. Most major foreign multinational corporations operating in Pakistan have their headquarters in Karachi. Karachi is also home to the Pakistan Stock Exchange, which was rated as Asia's best performing stock market in 2015 on the heels of Pakistan's upgrade to emerging-market status by MSCI.[141]

Media and technology

Karachi has been the pioneer in cable networking in Pakistan with the most sophisticated of the cable networks of any city of Pakistan,[142] and has seen an expansion of information and communications technology and electronic media. The city has become a software outsourcing hub for Pakistan. Several independent television and radio stations are based in Karachi, including Business Plus, AAJ News, Geo TV, KTN,[143] Sindh TV,[144] CNBC Pakistan, TV ONE, Express TV,[145] ARY Digital, Indus Television Network, Samaa TV, Abb Takk News, Bol TV, and Dawn News, as well as several local stations.

Industry

Industry contributes a large portion of Karachi's economy, with the city home to several of Pakistan's largest companies dealing in textiles, cement, steel, heavy machinery, chemicals, and food products.[146] The city is home to approximately 30 percent of Pakistan's manufacturing sector,[39] and produces approximately 42 percent of Pakistan's value added in large scale manufacturing.[147] At least 4500 industrial units form Karachi's formal industrial economy.[148] Karachi's informal manufacturing sector employs far more people than the formal sector, though proxy data suggest that the capital employed and value added from such informal enterprises is far smaller than that of formal sector enterprises.[149] An estimated 63% of the Karachi's workforce is employed in trade and manufacturing.[129]

Karachi Export Processing Zone, SITE, Korangi, Northern Bypass Industrial Zone, Bin Qasim and North Karachi serve as large industrial estates in Karachi.[150] The Karachi Expo Centre also complements Karachi's industrial economy by hosting regional and international exhibitions.[151]

| Name of estate | Location | Established | Area in acres |

|---|---|---|---|

| SITE Karachi | SITE Town | 1947 | 4700[152] |

| Korangi Industrial Area | Korangi Town | 1960 | 8500[153] |

| Landhi Industrial Area | Landhi Town | 1949 | 11000[154] |

| North Karachi Industrial Area | New Karachi Town | 1974 | 725[155] |

| Federal B Industrial Area | Gulberg Town | 1987 | [156] |

| Korangi Creek Industrial Park | Korangi Creek Cantonment | 2012 | 250[157] |

| Bin Qasim Industrial Zone | Bin Qasim Town | 1970 | 25000[158] |

| Karachi Export Processing Zone | Landhi Town | 1980[159] | 315[160] |

| Pakistan Textile City | Bin Qasim Town | 2004 | 1250[161] |

| West Wharf Industrial Area | Keamari Town | 430 | |

| SITE Super Highway Phase-I | Super Highway | 1983 | 300[162] |

| SITE Super Highway Phase-II | Super Highway | 1992 | 1000[162] |

Revenue collection

As home to Pakistan's largest ports and a large portion of its manufacturing base, Karachi contributes a large share of Pakistan's collected tax revenue. As most of Pakistan's large multinational corporations are based in Karachi, income taxes are paid in the city even though income may be generated from other parts of the country.[163] As home to the country's two largest ports, Pakistani customs officials collect the bulk of federal duty and tariffs at Karachi's ports, even if those imports are destined for one of Pakistan's other provinces.[164] Approximately 25% of Pakistan's national revenue is generated in Karachi.[37]

According to the Federal Board of Revenue's 2006–2007 year book, tax and customs units in Karachi were responsible for 46.75% of direct taxes, 33.65% of federal excise tax, and 23.38% of domestic sales tax.[165] Karachi accounts for 75.14% of customs duty and 79% of sales tax on imports,[165] and collects 53.38% of the total collections of the Federal Board of Revenue, of which 53.33% are customs duty and sales tax on imports.[165][166]

Demographics

Karachi is the most linguistically, ethnically, and religiously diverse city in Pakistan.[22] The city is a melting pot of ethno-linguistic groups from throughout Pakistan, as well as migrants from other parts of Asia. The city's inhabitants are referred to by the demonym Karachiite. The 2017 census numerated Karachi's population to be 14,910,352, having grown 2.49% per year since the 1998 census, which had listed Karachi's population at approximately 9.3 million.[167] The city's inhabitants are referred to by the demonym Karachiite in English, and Karāchīwālā in Urdu.

Population

At the end of the 19th century, Karachi had an estimated population of 105,000.[168] By the dawn of Pakistan's independence in 1947, the city had an estimated population of 400,000.[22] The city's population grew dramatically with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees from the newly independent Republic of India.[29] Rapid economic growth following independence attracted further migrants from throughout Pakistan and South Asia.[30] The 2017 census numerated Karachi's population to be 14,910,352, having grown 2.49% per year since the 1998 census, which had listed Karachi's population at approximately 9.3 million.[167]

Lower than expected population figures from the census suggest that Karachi's poor infrastructure, law and order situation, and weakened economy relative to other parts of Pakistan made the city less attractive to in-migration than previously thought.[167] The figure is disputed by all the major political parties in Sindh.[169][170][171] Karachi's population grew by 59.8% since the 1998 census to 14.9 million, while Lahore city grew 75.3%[172] – though Karachi's census district had not been altered by the provincial government since 1998, while Lahore's had been expanded by Punjab's government,[172] leading to some of Karachi's growth to have occurred outside the city's census boundaries.[167] Karachi's population had grown at a rate of 3.49% between the 1981 and 1998 census, leading many analysts to estimate Karachi's 2017 population to be approximately 18 million by extrapolating a continued annual growth rate of 3.49%. Some had expected that the city's population to be between 22 and 30 million,[167] which would require an annual growth rate accelerating to between 4.6% and 6.33%.[167]

Political parties in the province have suggested the city's population has been underestimated in a deliberate attempt to undermine the political power of the city and province.[173] Senator Taj Haider from the PPP claimed he had official documents revealing the city's population to be 25.6 million in 2013,[173] while the Sindh Bureau of Statistics, part of by the PPP-led provincial administration, estimated Karachi's 2016 population to be 19.1 million.[174]

| Population growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | %± | |

| 1729 | 250 | ||

| 1838 | 14,000 | 5,500.0% | |

| 1842 | 15,000 | 7.1% | |

| 1850 | 16,773 | 11.8% | |

| 1856 | 22,227 | 32.5% | |

| 1861 | 56,859 | 155.8% | |

| 1881 | 73,560 | 29.4% | |

| 1891 | 105,199 | 43.0% | |

| 1901 | 136,297 | 29.6% | |

| 1911 | 186,771 | 37.0% | |

| 1921 | 244,162 | 30.7% | |

| 1931 | 300,779 | 23.2% | |

| 1941 | 435,887 | 44.9% | |

| 1951 | 1,137,667 | 161.0% | |

| 1961 | 2,044,044 | 79.7% | |

| 1972 | 3,606,744 | 76.5% | |

| 1981 | 5,437,984 | 50.8% | |

| 1986 | 7,443,663 | 36.9% | |

| 1998 | 9,802,134 | 31.7% | |

| 2017 | 14,910,352 | 52.1% | |

| Source:[18][175][176][177] † Large population rise between 1941 and 1951 due to large-scale migration after independence in 1947. | |||

Ethnicity

The oldest portions of modern Karachi reflect the ethnic composition of the first settlement, with Balochis and Sindhis continuing to make up a large portion of the Lyari neighbourhood,[23] though many of the residents are relatively recent migrants. Following Partition, large numbers of Hindus left Pakistan for the newly independent Dominion of India (later the Republic of India), while a larger percentage of Muslim migrant and refugees from India settled in Karachi. The city grew 150% during the ten period between 1941 and 1951 with the new arrivals from India,[178] who made up 57% of Karachi's population in 1951.[179] The city is now considered a melting pot of Pakistan, and is the country's most diverse city.[23]

In 2011, an estimated 2.5 million foreign migrants lived in the city, mostly from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka.[180]

Much of Karachi's citizenry descend from Urdu-speaking migrants and refugees from North India who became known by the Arabic term for "Migrant": Muhajir. The first Muhajirs of Karachi arrived in 1946 in the aftermath of the Great Calcutta Killings and subsequent 1946 Bihar riots.[181] The city's wealthy Hindus opposed the resettlement of refugees near their homes, and so many refugees were accommodated in the older and more congested parts of Karachi.[182] The city witnessed a large influx of Muhajirs following Partition, who were drawn to the port city and newly designated federal capital for its white-collar job opportunities.[183] Muhajirs continued to migrate to Pakistan throughout the 1950s and early 1960s,[184] with Karachi remaining the primary destination of Indian Muslim migrants throughout those decades.[185] The Muhajir Urdu-speaking community in the 2017 census forms slightly less than 45% of the city's population.[172] Muhajirs form the bulk of Karachi's middle class.[23] Muhajirs are regarded as the city's most secular community, while other minorities such as Christians and Hindus increasingly regard themselves as part of the Muhajir community.[23]

Karachi is home to a wide array of non-Urdu speaking Muslim peoples from what is now the Republic of India. The city has a sizable community of Gujarati, Marathi, Konkani-speaking refugees.[23] Karachi is also home to a several-thousand member strong community of Malabari Muslims from Kerala in South India.[186] These ethno-linguistic groups are being assimilated in the Urdu-speaking community.[187]

During the period of rapid economic growth in the 1960s, large numbers Pashtuns from the NWFP migrated to Karachi with Afghan Pashtun refugees settling in Karachi during the 80's.[188][189][190][191][192] By some estimates, Karachi is home to the world's largest urban Pashtun population,[193] with more Pashtun citizens than the FATA.[2][193][193] While generally considered to be one of Karachi's most conservative communities, Pashtuns in Karachi generally vote for the secular Awami National Party rather than religious parties.[2] Pashtuns from Afghanistan are regarded as the most conservative community.[2] Pashtuns from Pakistan's Swat Valley, in contrast, are generally seen as more liberal in social outlook.[2] The Pashtun community forms the bulk of manual labourers and transporters.[194]

Migrants from Punjab began settling in Karachi in large numbers in the 1960s, and now make up an estimated 14% of Karachi's population.[2] The community forms the bulk of the city's police force,[2] and also form a large portion of Karachi's entrepreneurial classes and direct a larger portion of Karachi's service-sector economy.[2] The bulk of Karachi's Christian community, which makes up 2.5% of the city's population, is Punjabi.[195]

Despite being the capital of Sindh province, only 6–8% of the city is Sindhi.[2] Sindhis form much of the municipal and provincial bureaucracy.[2] 4% of Karachi's population speaks Balochi as its mother tongue, though most Baloch speakers are of Sheedi heritage – a community that traces its roots to Africa.[2]

Following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 and independence of Bangladesh, thousands of Urdu-speaking Biharis arrived in the city, preferring to remain Pakistani rather than live in the newly independent country. Large numbers of Bengalis also migrated from Bangladesh to Karachi during periods of economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s. Karachi is now home to an estimated 2.5 to 3 million ethnic Bengalis living in Pakistan.[32][33] Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, who speak a dialect of Bengali and are sometimes regarded as Bengalis, also live in the city. Karachi is home to an estimated 400,000 Rohingya residents.[196][197] Large scale Rohingya migration to Karachi made Karachi one of the largest population centres of Rohingyas in the world outside of Myanmar.[198]

Central Asian migrants from Uzbekistan and Kyrghyzstan have also settled in the city.[199] Domestic workers from the Philippines are employed in Karachi's posh locales, while many of the city's teachers hail from Sri Lanka.[199] Expatriates from China began migrating to Karachi in the 1940s, to work as dentists, chefs and shoemakers, while many of their decedents continue to live in Pakistan.[199][200] The city is also home to a small number of British and American expatriates.[201]

During World War II, about 3,000 Polish refugees from the Soviet Union, with some Polish families who chose to remain in the city after Partition.[202][203] Post-Partition Karachi also once had a sizable refugee community from post-revolutionary Iran.[199]

Religion

Karachi is one of Pakistan's most religiously diverse cities.[22] Karachiites adhere to numerous sects and sub-sects of Islam, as well as Protestant Christianity, and community of Goan Catholics. The city also is home to large numbers of Hindus, and a small community of Zoroastrians. According to Nichola Khan Karachi is also the world's largest Muslim city.[209]

Prior to Pakistan's independence in 1947, the population of the city was estimated to be 50% Muslim, 40% Hindu, with the remaining 10% primarily Christians (both British and native), with a small numbers of Jews. Following the independence of Pakistan, much of Karachi's Sindhi Hindu population left for India while Muslim refugees from India in turn settled in the city. The city continued to attract migrants from throughout Pakistan, who were overwhelmingly Muslim, and city's population nearly doubled again in the 1950s.[178] As a result of continued migration, over 96.5% of the city currently is estimated to be Muslim.[2]

Karachi is overwhelmingly Muslim,[2] though the city is one of Pakistan's most secular cities.[23][24][25] Approximately 85% of Karachi's Muslims are Sunnis, while 15% are Shi'ites.[210][211][212] Sunnis primarily follow the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, with Sufism influencing religious practices by encouraging reverence for Sufi saints such as Abdullah Shah Ghazi and Mewa Shah. Shi'ites are predominantly Twelver, with a significant Ismaili minority which is further subdivided into Nizaris, Mustaalis, Dawoodi Bohras, and Sulaymanis.

Approximately 2.5% of Karachi's population is Christian.[204][205][206] The city's Christian community is primarily composed of Punjabi Christians,[195] who converted from Sikhism to Christianity during the British Raj.[213] Karachi has a community of Goan Catholics who are typically better-educated and more affluent than their Punjabi co-religionists.[214] They established the posh Cincinnatus Town in Garden East as a Goan enclave. The Goan community dates from 1820 and has a population estimated to be 12,000–15,000 strong.[215] Karachi is served by its own archdiocese, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Karachi.

While most of the city's Hindu population left en masse for India following Pakistan's independence, Karachi still has a large Hindu community with an estimated population of 250,000 based on 2013 data,[216] with several active temples in central Karachi. The Hindu community is split into a more affluent Sindhi Hindu and small Punjabi Hindu group that forms part of Karachi's educated middle class, while poorer Hindus of Rajasthani and Marwari descent form the other part and typically serve as menial and day laborers. Wealthier Hindus live primarily in Clifton and Saddar, while poorer ones live and have temples in Narayanpura and Lyari. Many streets in central Karachi still retain Hindu names, especially in Mithadar, Aram Bagh (formerly Ram Bagh), and Saddar.

Karachi's affluent and influential Parsis have lived in the region in the 12th century, though the modern community dates from the mid 19th century when they served as military contractors and commissariat agents to the British.[217] Further waves of Parsi immigrants from Persia settled in the city in the late 19th century.[218] The population of Parsis in Karachi and throughout South Asia is in continuous decline due to low birth-rates and migration to Western countries.[219] According to Framji Minwalla approximately 1,092 Parsis left in Pakistan.[220]

Language

Karachi has the largest number of Urdu speakers in Pakistan.[142] As per the 1998 census, the linguistic breakdown of Karachi Division is:

| Rank | Language | 1998 census[221] | Speakers | 1981 census[222] | Speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Urdu | 48.52% | 4,497,747 | 54.34% | 2,830,098 |

| 2 | Punjabi | 13.94% | 1,292,335 | 13.64% | 710,389 |

| 3 | Pashto | 11.42% | 1,058,650 | 8.71% | 453,628 |

| 4 | Sindhi | 7.22% | 669,340 | 6.29% | 327,591 |

| 5 | Balochi | 4.34% | 402,386 | 4.39% | 228,636 |

| 6 | Saraiki | 2.11% | 195,681 | 0.35% | 18,228 |

| 7 | Others | 12.44% | 1,153,126 | 12.27% | 639,560 |

| All | 100% | 9,269,265 | 100% | 5,208,132 |

The category of "others" includes Gujarati, Dawoodi Bohra, Memon, Marwari, Dari, Brahui, Makrani, Hazara, Khowar, Gilgiti, Burushaski, Balti, Arabic, Farsi and Bengali.[223] The number of Sindhi speakers in Karachi is growing as many are moving from rural areas to the city.[224]

Transportation

Road

Karachi is served by a road network estimated to be approximately 9,500 kilometres (5,900 miles) in length,[225] serving approximately 3.1 million vehicles per day.

Karachi is served by three "Signal-Free Corridors" which are designed as urban express roads to permit traffic to transverse large distances without the need to stop at intersections and stop lights. The first opened in 2007 and connects Shah Faisal Town in eastern Karachi to the industrial-estates in SITE Town 10.5 km (6 1⁄2 mi) away. The second corridor connects Surjani Town with Shahrah-e-Faisal over a 19-kilometre span, while the third stretch 28 km (17 1⁄2 mi) and connects Karachi's urban centre to the Gulistan-e-Johar suburb. A fourth corridor that will link Karachi's centre to Karachi's Malir Town is currently under construction.

Karachi is the terminus of the M-9 motorway, which connects Karachi to Hyderabad. The road is a part of a much larger motorway network under construction as part of the expansive China Pakistan Economic Corridor. From Hyderabad, motorways have been built, or are being constructed, to provide high-speed road access to the northern Pakistani cities of Peshawar and Mansehra 1,100 km (700 mi) to the north of Karachi.

Karachi is also the terminus of the N-5 National Highway which connects the city to the historic medieval capital of Sindh, Thatta. It offers further connections to northern Pakistan and the Afghan border near Torkham, as well as the N-25 National Highway which connects the port city to the Afghan border near Quetta.

Within the city of Karachi, the Lyari Expressway is a controlled-access highway along the Lyari River in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. As of 8 February 2018 Lyari Expressway's north-bound and south-bound sections are both complete and open for traffic.[226] This toll highway is designed to relieve congestion in the city of Karachi. To the north of Karachi lies the Karachi Northern Bypass (M10), which starts near the junction of the M9. It then continues north for a few kilometres before turning west, where it intersects the N25.

Rail

Karachi is linked by rail to the rest of the country by Pakistan Railways. The Karachi City Station and Karachi Cantonment Railway Station are the city's two major railway stations.[2] The city has an international rail link, the Thar Express which links Karachi Cantonment Station with Bhagat Ki Kothi station in Jodhpur, India.[227]

The railway system also handles freight linking Karachi port to destinations up-country in northern Pakistan.[228] The city is the terminus for the Main Line-1 Railway which connects Karachi to Peshawar. Pakistan's rail network, including the Main Line-1 Railway is being upgraded as part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, allowing trains to depart Karachi and travel on Pakistani railways at an average speed of 160 km/h (100 mph) versus the average 60 to 105 km/h (35 to 65 mph) speed currently possible on existing track.[229]

Public transport

Karachi's public transport infrastructure is inadequate and constrained by low levels of investment.[230] Karachi is not currently served by any municipal public transit, and is instead serviced primarily by the private and informal sector.[231]

Metrobus

The Pakistani Government is developing the Karachi Metrobus project, which is a multi-line 112.9-kilometre (70 1⁄4-mile) bus rapid transit system currently under construction.[232] The Metrobus project was inaugurated by then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on 25 February 2016. Sharif said the "project will be more beautiful than Lahore Metro Bus".[233] The projects initial launch date was February 2017, but due to the slow pace of work, it is not yet operational. The Metrobus project has also been criticized for not being accessible by wheelchair-bound individuals[234]

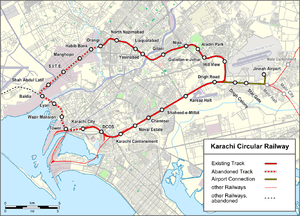

Karachi Circular Railway

Karachi was once served by the Karachi Circular Railway that was started in 1969 and closed in 1999.[235] A tramway service was started in 1884 in Karachi but was closed in 1975 because of some reasons.[236][237] While the Japanese Government has expressed willingness to help fund the refurbishment of the Karachi Circular Railway,[238] the project has not been finalized. In March 2020, Minister of Railways Sheikh Rasheed Ahmed said that the Karachi Circular Railway "will be operationalized in six months" in collaboration with the government of Sindh.[239] In the budget of fiscal year 2020–21, Rs1,500 million has been allocated for the operationalisation of train on existing KCR alignment.[240] In the budget of fiscal year 2020–21, Sindh Government enmarked Rs207 billion for the revival of KCR.[241]

Air

Karachi's Jinnah International Airport is the busiest airport of Pakistan with a total of 7.2 million passengers in 2018.[242] The current terminal structure was built in 1992, and is divided into international and domestic sections. Karachi's airport serves as a hub for the flag carrier, Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), as well as for Air Indus, Serene Air and airblue. The airport offers non-stop flights to destinations throughout East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf States, Europe and North America.[243][244]

Sea

The largest shipping ports in Pakistan are the Port of Karachi and the nearby Port Qasim, the former being the oldest port of Pakistan. Port Qasim is located 35 kilometres (22 miles) east of the Port of Karachi on the Indus River estuary. These ports handle 95% of Pakistan's trade cargo to and from foreign ports. These seaports have modern facilities which include bulk handling, containers and oil terminals.[245]

Civic administration

City government

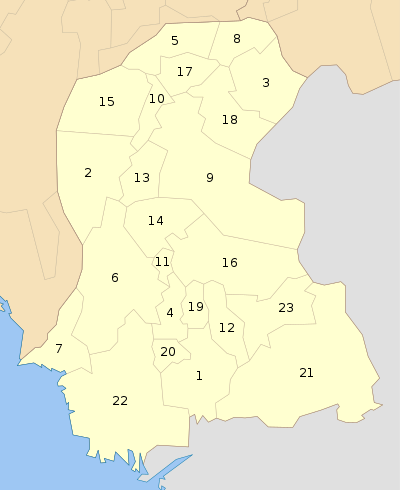

Karachi has a fragmented system of civic government. The urban area is divided into six District Municipal Corporations: Karachi East, Karachi West, Karachi Central, Karachi South, Malir, Korangi. Each district is further divided into between 22 and 42 Union Committees. Each Union Committee is represented by seven elected representatives, four of whom can be general candidates of any background; the other three seats are reserved for women, religious minorities, and a union representative or peasant farmer.

Karachi's urban area also includes six cantonments, which are administered directly by the Pakistani military, and include some of Karachi's most desirable real-estate.

Key civic bodies, such as the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board and KBCA (Karachi Building Control Authority), among others, are under the direct control of the Government of Sindh.[246] Additionally, Karachi's city-planning authority for undeveloped land, the Karachi Development Authority, is under control of the government, while two new city-planning authorities, the Lyari Development Authority and Malir Development Authority were revived by the Pakistan Peoples Party government in 2011 – allegedly to patronize their electoral allies and voting banks.[247]

Historical background

In response to a cholera epidemic in 1846, the Karachi Conservancy Board was organized by British administrators to control its spread.[248][249] The board became the Karachi Municipal Commission in 1852, and the Karachi Municipal Committee the following year.[248] The City of Karachi Municipal Act of 1933 transformed the city administration into the Karachi Municipal Corporation with a mayor, a deputy mayor and 57 councillors.[248] In 1976, the body became the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation.[248]

During the 1900s, Karachi saw its major beautification project under the mayoralty of Harchandrai Vishandas. New roads, parks, residential, and recreational areas were developed as part of this project. In 1948, the Federal Capital Territory of Pakistan was created, comprising approximately 2,103 km2 (812 sq mi) of Karachi and surrounding areas, but this was merged into the province of West Pakistan in 1961.[250] In 1996, the metropolitan area was divided into five districts, each with its own municipal corporation.[248]

Union councils (2001–11)

In 2001, during the rule of General Pervez Musharraf, five districts of Karachi were merged to form the city district of Karachi, with a three-tier structure. The two most local tiers are composed of 18 towns, and 178 union councils.[251] Each tier focused on elected councils with some common members to provide "vertical linkage" within the federation.[252]

Naimatullah Khan was the first Nazim of Karachi during the Union Council period, while Shafiq-Ur-Rehman Paracha was the first district co-ordination officer of Karachi. Syed Mustafa Kamal was elected City Nazim of Karachi to succeed Naimatullah Khan in 2005 elections, and Nasreen Jalil was elected as the City Naib Nazim.

Each Union Council had thirteen members elected from specified electorates: four men and two women elected directly by the general population; two men and two women elected by peasants and workers; one member for minority communities; two members are elected jointly as the Union Mayor (Nazim) and Deputy Union Mayor (Naib Nazim).[253] Each council included up to three council secretaries and a number of other civil servants. The Union Council system was dismantled in 2011.

District Municipal Corporations (2011–present)

In July 2011, city district government of Karachi was reverted its original constituent units known as District Municipal Corporations (DMC). The five original DMCs are: Karachi East, Karachi West, Karachi Central, Karachi South and Malir. In November 2013, a sixth DMC, Korangi District was carved out from District East.[254][255][256][257][258]

The committees for each district devise and enforce land-use and zoning regulations within their district. Each committee also manages water supply, sewage, and roads (except for 28 main arteries, which are managed by the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation).[89] Street lighting, traffic planning, markets regulations, and signage are also under the control of the DMCs. Each DMC are also maintains its own municipal record archive, and devises its own local budget.[89]

Municipal Administration of Karachi is also run by the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), which is responsible for the development and maintenance of main arteries, bridges, drains, several hospitals, beaches, solid waste management, as well as some parks, and the city's firefighting services.[259] The Karachi mayor since 2016 is Waseem Akhtar, with Arshad Hassan serving as Deputy Mayor; both serve as part of the KMC. The Metropolitan Commissioner of the KMC is Dr. Syed Saif-ur-Rehman.[260]

The position of Commissioner of Karachi was created, with Iftikhar Ali Shallwani serving this role.[261] There are six military cantonments, which are administered by the Pakistani Army, and are some of Karachi's most upscale neighbourhoods.

Karachi South |

|

City planning

The Karachi Development Authority (KDA), along with the Lyari Development Authority (LDA) and Malir Development Authority (MDA), is responsible for the development of most undeveloped land around Karachi. KDA came into existence in 1957 with the task of managing land around Karachi, while the LDA and MDA were formed in 1993 and 1994, respectively. KDA under the control of Karachi's local government and mayor in 2001, while the LDA and MDA were abolished. KDA was later placed under direct control of the Government of Sindh in 2011. The LDA and MDA were also revived by the Pakistan Peoples Party government at the time, allegedly to patronize their electoral allies and voting banks.[247] City-planning in Karachi, therefore, is not locally directed but is instead controlled at the provincial level.

Each District Municipal Corporation regulate land-use in developed areas, while the Sindh Building Control Authority ensures that building construction is in accordance with building & town planning regulations. Cantonment areas, and the Defence Housing Authority are administered and planned by the military.

Municipal services

Water

Municipal water supplies are managed by the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KW&SB), which supplies 640 million gallons daily (MGD) to the city (excluding the city's steel mills and Port Qasim), of which 440 MGD are filtered/treated.[89] Most of the supply comes from the Indus River, and 90 MGD from the Hub Dam.[89] Karachi's water supply is transported to the city through a complex network of canals, conduits, and siphons, with the aid of pumping and filtration stations.[89] 76% of Karachi households have access to piped water as of 2015,[262] with private water tankers supplying much of the water required in informal settlements.[129] 18% of residents in a 2015 survey rated their water supply as "bad" or "very bad", while 44% expressed concern at the stability of water supply.[262] By 2015, an estimated 30,000 people were dying due to water-borne diseases annually.[263]

The K-IV water project is under development at a cost of $876 million. It is expected to supply 650 million gallons daily of potable water to the city, the first phase 260 million gallons upon completion.[264][265]

Sanitation

98% of Karachi's households are connected to the city's underground public sewerage system,[262] largely operated by the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KW&SB). The KW&SB operates 150 pumping stations, 25 bulk reservoirs, over 10,000 kilometres of pipes, and 250,000 manholes.[89] The city generates approximately 472 million gallons daily (MGD) of sewage, of which 417 MGD are discharged without treatment.[89] KW&SB has the optimum capacity to treat up to 150 MGD of sewage, but uses only about 50 MGD of this capacity.[89] Three treatment plants are available, in SITE Town, Mehmoodabad, and Mauripur.[89] 72% reported in 2015 that Karachi's drainage system overflows or backs up,[262] the highest percentage of all major Pakistani cities.[262] Parts of the city's drainage system overflow on average 2–7 times per month, flooding some city streets.[262]

Households in Orangi self-organized to set-up their own sewerage system under the Orangi Pilot Project,[266] a community service organization founded in 1980. 90% of Orangi streets are now connected to a sewer system built by local residents under the Orangi Pilot Project.[266] Residents of individual streets bear the cost of sewerage pipes, and provide volunteer labour to lay the pipe.[266] Residents also maintain the sewer pipes,[266] while the city municipal administration has built several primary and secondary pipes for the network.[266] As a result of OPP, 96% of Orangi residents have access to a latrine.[266]

The Sindh Solid Waste Management Board (SSWMB) is responsible for the collection and disposal of solid waste, not only in Karachi but throughout the whole province. Karachi has the highest percentage of residents in Pakistan who report that their streets are never cleaned – 42% of residents in Karachi report their streets are never cleaned, compared to 10% of residents in Lahore.[262] Only 17% of Karachi residents reporting daily street cleaning, compared to 45% in Lahore.[262] 69% of Karachi residents rely on private garbage collection services,[262] with only 15% relying on municipal garbage collection services.[262] 57% of Karachi residents in a 2015 survey reported that the state of their neighbourhood's cleanliness was either "bad" or "very bad".[262] compared to 35% in Lahore,[262] and 16% in Multan.[262]

Education

Primary and secondary

Karachi's primary education system is divided into five levels: primary (grades one through five); middle (grades six through eight); high (grades nine and ten, leading to the Secondary School Certificate); intermediate (grades eleven and twelve, leading to a Higher Secondary School Certificate); and university programs leading to graduate and advanced degrees. Karachi has both public and private educational institutions. Most educational institutions are gender-based, from primary to university level alongside the co education institutions.

Several of Karachi's schools, such as St Patrick's High School, St Joseph's Convent School and St Paul's English High School, are operated by Christian churches, and among Pakistan's most prestigious schools.

Higher

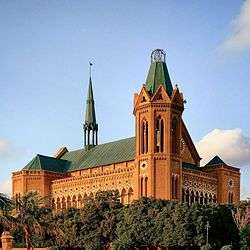

Karachi is home to several major public universities. Karachi's first public university's date from the British colonial era. The Sindh Madressatul Islam founded in 1885, was granted university status in 2012. Establishment of the Sindh Madressatul Islam was followed by the establishment of the D. J. Sindh Government Science College in 1887, and the institution was granted university status in 2014. The Nadirshaw Edulji Dinshaw University of Engineering and Technology (NED), was founded in 1921, and is Pakistan's oldest institution of higher learning. The Dow University of Health Sciences was established in 1945, and is now one of Pakistan's top medical research institutions.

The University of Karachi, founded in 1951, is Pakistan's largest university with a student population of 24,000. The Institute of Business Administration (IBA), founded in 1955, is the oldest business school outside of North America and Europe, and was set up with technical support from the Wharton School and the University of Southern California. The Dawood University of Engineering and Technology, which opened in 1962, offers degree programmes in petroleum, gas, chemical, and industrial engineering. The Pakistan Navy Engineering College (PNEC), operated by the Pakistan Navy, is associated with the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) in Islamabad.

Karachi is also home to numerous private universities. The Aga Khan University, founded in 1983, is Karachi's oldest private educational institution, and is one of Pakistan's most prestigious medical schools. The Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture was founded in 1989, and offers degree programmes in arts and architectural fields. Hamdard University is the largest private university in Pakistan with faculties including Eastern Medicine, Medical, Engineering, Pharmacy, and Law. The National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences (NUCES-FAST), one of Pakistan's top universities in computer education, operates two campuses in Karachi. Bahria University (BU) founded in 2000, is one of the major general institutions of Pakistan with their campuses in Karachi, Islamabad and Lahore offers degree programs in Management Sciences, Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Psychology. Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology (SSUET) offers degree programmes in biomedical, electronics, telecom and computer engineering. Karachi Institute of Economics & Technology (KIET) has two campuses in Karachi. The Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST), founded in 1995 by former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, operates a campus in Karachi.

- Iqra University

- Habib University

Habib University is a liberal arts college in Karachi.

Habib University is a liberal arts college in Karachi. - Dow University

- Jinnah Medical and Dental College

- Jinnah Sindh Medical University

- Pakistan Air Force – Karachi Institute of Economics and Technology

- United Medical and Dental College

- Liaquat National Medical College

- Institute of Cost & Management Accountants of Pakistan (ICMAP)

- Institute of Business Management (CBM)

Healthcare

Karachi is a centre of research in biomedicine with at least 30 public hospitals, 80 registered private hospitals and 12 recognized medical colleges,[267] including the Indus Hospital, Lady Dufferin Hospital, Karachi Institute of Heart Diseases,[268] National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases,[269] Civil Hospital,[270] Combined Military Hospital,[271] PNS Rahat,[272] PNS Shifa,[273] Aga Khan University Hospital, Liaquat National Hospital, Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre,[274] Holy Family Hospital[275] and Ziauddin Hospital. In 1995, Ziauddin Hospital was the site of Pakistan's first bone marrow transplant.[276]

Karachi municipal authorities in October 2017 launched a new early warning system that alerted city residents to a forecasted heatwave. Previous heatwaves had routinely claimed lives in the city, but implementation of the warning system was credited for no reported heat-related fatalities.[117]

Entertainment, arts and culture

Entertainment and shopping malls

Karachi is home to Pakistan and South Asia's largest shopping mall, Lucky One Mall which hosts more than two hundred stores.[277] According to TripAdvisor the city is also home to Pakistan's favorite shopping mall, Dolmen Mall, Clifton which was also featured on CNN[278] and the country's favorite entertainment complex, Port Grand.[279] In 2019 the city is expected to add another mega mall/entertainment complex at Bahria Icon Tower Clifton, Pakistan's tallest skyscraper.[280][281]

Museums and galleries

Karachi is home to several of Pakistan's most important museums. The National Museum of Pakistan and Mohatta Palace display artwork, while the city also has several private art galleries.[282] The city is also home to the Pakistan Airforce Museum and Pakistan Maritime Museum are also located in the city. Wazir Mansion, the birthplace of Pakistan's founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah has also been preserved as a museum open to the public.

Theatre and Cinema

Karachi is home to some of Pakistan's important cultural institutions. The National Academy of Performing Arts,[283] located in the former Hindu Gymkhana, offers diploma courses in performing arts including classical music and contemporary theatre. Karachi is home to groups such as Thespianz Theater, a professional youth-based, non-profit performing arts group, which works on theatre and arts activities in Pakistan.[284][285]

Though Lahore is considered to be home of Pakistan's film industry, Karachi is home to Kara Film Festival annually showcases independent Pakistani and international films and documentaries.[286]

Cinema Bambino Cinema, Capri Cinema, Cinepax Cinema, Mega Multiplex Cinema – Millennium Mall, Nueplex Cinemas, Atrium Mall.

Music

The All Pakistan Music Conference, linked to the 45-year-old similar institution in Lahore, has been holding its annual music festival since its inception in 2004.[287] The National Arts Council (Koocha-e-Saqafat) has musical performances and mushaira.

Tourist attractions

Karachi is a tourist destination for domestic and international tourists. Tourist attractions near Karachi city include:

Museums: Museums located in Karachi include the National Museum of Pakistan, Pakistan Air Force Museum, and Pakistan Maritime Museum.

Parks: Parks located in Karachi include Bagh Ibne Qasim, Boat Basin Park, Mazar-e-Quaid, Karachi Zoo, Hill Park, Safari Park, Bagh-e-Jinnah, PAF Museum Park and Maritime Museum Park.

Social issues

Crime

Sometimes stated to be amongst the world's most dangerous cities,[288] the extent of violent crime in Karachi is not as significant in magnitude as compared to other cities.[289] According to the Numbeo Crime Index 2014, Karachi was the 6th most dangerous city in the world. By the middle of 2016, Karachi's rank had dropped to 31 following the launch of anti-crime operations.[290] By 2018, Karachi's ranking has dropped to 50.[291] In mid 2019, Karachi's ranking fell to 71, ranking it safer than regional cities such as Delhi (65th place) and Dhaka (34th place), but was still higher than Mumbai (172nd place) and Lahore (201st place).[292]

The city's large population results in high numbers of homicides with a moderate homicide rate.[289] Karachi's homicide rates are lower than many Latin American cities,[289] and in 2015 was 12.5 per 100,000[293] – lower than the homicide rate of several American cities such as New Orleans and St. Louis.[294] The homicide rates in some Latin American cities such as Caracas, Venezuela and Acapulco, Mexico are in excess of 100 per 100,000 residents,[294] many times greater than Karachi's homicide rate. In 2016, the number of murders in Karachi had dropped to 471, which had dropped further to 381 in 2017.[295]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Karachi was rocked by political conflict while crime rates drastically increased with the arrival of weaponry from the War in Afghanistan.[46] Several of Karachi's criminal mafias became powerful during a period in the 1990s described as "the rule of the mafias."[296] Major mafias active in the city included land mafia, water tanker mafia, transport mafia and a sand and gravel mafia.[297][296][298][299] Karachi's highest death rates occurred in the mid 1990s when Karachi was much smaller. In 1995, 1,742 killings were recorded,[300] when the city had over five million fewer residents.[301]

Karachi Operation

Karachi had become widely known for its high rates of violent crime, but rates sharply decreased following a controversial crackdown operation against criminals, the MQM party, and Islamist militants initiated in 2013 by the Pakistan Rangers.[47] In 2015, 1,040 Karachiites were killed in either acts of terror or other crime – an almost 50% decrease from the 2,023 killed in 2014,[302] and an almost 70% decrease from the 3,251 recorded killed in 2013 – the highest ever recorded number in Karachi history.[303] Despite a sharp decrease in violent crime, street crime remains high.[304]

With 650 homicides in 2015, Karachi's homicide rate decreased by 75% compared to 2013.[305] In 2017, the number of homicides had dropped further to 381.[295] Extortion crimes decreased by 80% between 2013 and 2015, while kidnappings decreased by 90% during the same period.[305] By 2016, the city registered a total of 21 cases of kidnap for ransom.[306] Terrorist incidents dropped by 98% between 2012 and 2017, according to Pakistan's Interior Ministry.[307] As a result of the Karachi's improved security environment, real-estate prices in Karachi rose sharply in 2015,[308] with a rise in business for upmarket restaurants and cafés.[309]

Ethnic conflict

Insufficient affordable housing infrastructure to absorb growth has resulted in the city's diverse migrant populations being largely confined to ethnically homogenous neighbourhoods.[129] The 1970s saw major labour struggles in Karachi's industrial estates. Violence originated in the city's university campuses, and spread into the city.[310] Conflict was especially sharp between MQM party and ethnic Sindhis, Pashtuns, and Punjabis. The party and its vast network of supporters were targeted by Pakistani security forces as part of the controversial Operation Clean-up in 1992, as part of an effort to restore peace in the city that lasted until 1994.[112]

Poor infrastructure

Urban planning and service delivery have not kept pace with Karachi's growth, resulting in the city's low ranking on livability rankings.[129] The city has no cohesive transportation policy, and no official public transit system, though up to 1,000 new cars are added daily to the city's congested streets.[129]

Unable to provide housing to large numbers of refugees shortly after independence, Karachi's authorities first issued "slips" to refugees beginning in 1950 – which allowed refugees to settle on any vacant land.[266] Such informal settlements are known as katchi abadis, and now approximately half the city's residents live in these unplanned communities.[129]

Architecture

_Head_Office_Building_Karachi.jpg)

Karachi Chamber of Commerce Building

Karachi Chamber of Commerce Building

Katrak Bandstand at the Jehangir Kothari Parade

Katrak Bandstand at the Jehangir Kothari Parade

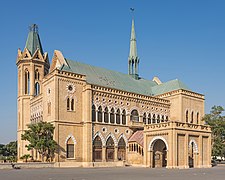

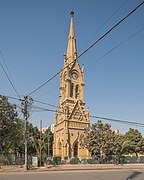

Karachi has a collection of buildings and structures of varied architectural styles. The downtown districts of Saddar and Clifton contain early 20th-century architecture, ranging in style from the neo-classical KPT building to the Sindh High Court Building. Karachi acquired its first neo-Gothic or Indo-Gothic buildings when Frere Hall, Empress Market and St. Patrick's Cathedral were completed. The Mock Tudor architectural style was introduced in the Karachi Gymkhana and the Boat Club. Neo-Renaissance architecture was popular in the 19th century and was the architectural style for St. Joseph's Convent (1870) and the Sind Club (1883).[311] The classical style made a comeback in the late 19th century, as seen in Lady Dufferin Hospital (1898)[312] and the Cantt. Railway Station. While Italianate buildings remained popular, an eclectic blend termed Indo-Saracenic or Anglo-Mughal began to emerge in some locations.[313] The local mercantile community began acquiring impressive structures. Zaibunnisa Street in the Saddar area (known as Elphinstone Street in British days) is an example where the mercantile groups adopted the Italianate and Indo-Saracenic style to demonstrate their familiarity with Western culture and their own. The Hindu Gymkhana (1925) and Mohatta Palace are examples of Mughal revival buildings.[314] The Sindh Wildlife Conservation Building, located in Saddar, served as a Freemasonic Lodge until it was taken over by the government. There are talks of it being taken away from this custody and being renovated and the Lodge being preserved with its original woodwork and ornate wooden staircase.[315]

Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture is one of the prime examples of Architectural conservation and restoration where an entire Nusserwanjee building from Kharadar area of Karachi has been relocated to Clifton for adaptive reuse in an art school. The procedure involved the careful removal of each piece of timber and stone, stacked temporarily, loaded on the trucks for transportation to the Clifton site, unloaded and re-arranged according to a given layout, stone by stone, piece by piece, and completed within three months.[316]

Architecturally distinctive, even eccentric, buildings have sprung up throughout Karachi. Notable example of contemporary architecture include the Pakistan State Oil Headquarters building. The city has examples of modern Islamic architecture, including the Aga Khan University hospital, Masjid e Tooba, Faran Mosque, Bait-ul Mukarram Mosque, Quaid's Mausoleum, and the Textile Institute of Pakistan. One of the unique cultural elements of Karachi is that the residences, which are two- or three-story townhouses, are built with the front yard protected by a high brick wall. I. I. Chundrigar Road features a range of extremely tall buildings. The most prominent examples include the Habib Bank Plaza, PRC Towers and the MCB Tower which is the tallest skyscraper in Pakistan.[317]

Sports

When it comes to sports Karachi has a distinction, because some sources cite that it was in 1877 at Karachi in (British) India, where the first attempt was made to form a set of rules of badminton[318] and likely place is said to Frere Hall.

Cricket's history in Pakistan predates the creation of the country in 1947. The first ever international cricket match in Karachi was held on 22 November 1935 between Sindh and Australian cricket teams. The match was seen by 5,000 Karachiites.[319] Karachi is also the place that innovated tape ball, a safer and more affordable alternative to cricket.[320]

The inaugural first-class match at the National Stadium was played between Pakistan and India on 26 February 1955 and since then Pakistani national cricket team has won 20 of the 41 Test matches played at the National Stadium.[321] The first One Day International at the National Stadium was against the West Indies on 21 November 1980, with the match going to the last ball.

The national team has been less successful in such limited-overs matches at the ground, including a five-year stint between 1996 and 2001, when they failed to win any matches. The city has been host to a number of domestic cricket teams including Karachi,[322] Karachi Blues,[323] Karachi Greens,[324] and Karachi Whites.[325] The National Stadium hosted two group matches (Pakistan v. South Africa on 29 February and Pakistan v. England on 3 March), and a quarter-final match (South Africa v. West Indies on 11 March) during the 1996 Cricket World Cup.[326]