Silk in the Indian subcontinent

Silk in the Indian subcontinent is a luxury good. In India, about 97% of the raw mulberry silk is produced in the five Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Jammu and Kashmir.[1] Mysore and North Bangalore, the upcoming site of a US$20 million "Silk City", contribute to a majority of silk production.[2] Another emerging silk producer is Tamil Nadu where mulberry cultivation is concentrated in Salem, Erode and Dharmapuri districts. Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh and Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu were the first locations to have automated silk reeling units.[3]

History

The Silk Road

Recent archaeological discoveries in Harappa and Chanhu-daro suggest that sericulture, employing wild silk threads from native silkworm species, existed in South Asia during the time of the Indus Valley Civilization dating between 2450 BC and 2000 BC, while evidence for silk production in China back to around 2570 BC and earlier.[4][5] The Indus silks were obtained from more than one species Antheraea and Philosamia (eri silk). Antheraea assamensis and A. mylitta were widely used. These findings were published in the journal Archaeometry[4] by archaeologists from Harvard University who examined the silk fibre excavated from two Indus valley cities of Harappa and Chanhudaro. The fibres were dated to around 2450–2000 BCE and were processed using similar techniques of degumming and reeling as that of the Chinese. Scanning electron micrographs of the fibre revealed that some fibres were spun after the silk moth was allowed to escape from the cocoon, similar to the ahimsa silk promoted by Mahatma Gandhi. Nevasa in 1500 BC also provides evidence of silk weaving, Arthashastra written around 4th century BC mentions a guild of silk weavers. Gupta inscriptions also mention this guild. Most of the silk was exported using Indian ocean trade and India was a major silk exporter during the Gupta periods. Romans imported all of their silk from India but Persians created a monopoly of the Indian silk trade hence Byzantine empire sought Silk route to not only import silk but introduce silk weaving in Western Asia and Europe.

Silk goes to India

The brocade weaving centres of India developed in and around the capitals of kingdoms or holy cities because of the demand for expensive fabrics by the royal families and temples. Rich merchants of the trading ports or centres also contributed to the development of these fabrics. Besides trading in the finished product, they advanced money to the weavers to buy the costly raw materials that is silk and zari. The ancient centres were situated mainly in Gujarat, Malwa and South India. In the north, Delhi, Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Varanasi, Mau, Azamgarh and Murshidabad were the main centres for brocade weaving. Northern weavers were greatly influenced by the brocade weaving regions of eastern and southern Persia, Turkey, Central Asia and Afghanistan.

Gujrati builders and weavers were brought by Akbar to the royal workshops in 1572 AD. Akbar took an active role in overseeing the royal textile workshops, established at Lahore, Agra and Fatehpur Sikri where skilled weavers from different backgrounds worked. Expert weavers from those distant lands worked with the local weavers and imparted their skills to the locals. This intermingling of creative techniques brought about a great transformation in the textile weaving industry. The exquisite latifa (beautiful) buti was the outcome of the fusion of Persian and Indian designs. Brocades produced at the royal workshops of other well-known Muslim centres in Syria, Egypt, Turkey and Persia were also exported to India. Under the Mughals, sericulture and silk-weaving received special encouragement and silk cloth produced in the Punjab came to be prized throughout the world. Lahore and Multan developed into major centres of silk industry. The tradition continues.

See also: Assam silk, Tussar silk

Types of silk cloth

Kinkhwab (brocade)

Kinkhwab was originally an elegant, heavy silk fabric with a floral or figured pattern known most for its butis and jals woven with silk as the warp and tilla as the weft, produced in China and Japan. Tilla in the earlier times was known as kasab. It was a combination of silver and tamba (copper) which was coated with a veneer of gold and silver. Kinkhwabs have also been known as ‘Kimkhabs’, ‘Kamkhwabs’, ‘Kincobs’, ‘Zar-baft’ (Gold Woven), zartari, zarkashi, mushaiar.[6]

Kam means little or scarcely. Khwab means a dream and it is said that even with such a name ‘Its beauty, splendor and elegance can be hardly dreamt of’. Kinkhwabs are heavy fabrics or several layers of warp threads with an elaborate all-over pattern of extra weft, which may be of silk, gold and / or silver threads or combinations. There may be three to seven layers of warp threads. (Tipara means three layers and Chaupara means four layers to Satpara meaning seven layers). Kin means golden in Chinese. Its specialty is in profusely using the gold and silver thread in a manner that sometimes leaves the silk background hardly visible.

When the figure work is in silver threads with a background of gold threads it is called ‘Tashi Kinkhwab’. This is a variety of kinkhwab which has a ground worked with an extra warp of gold [badla (flat wire) zari] and the pattern created with an extra weft of silver badla zari or vice versa. A satin weave is very often used, resulting in a smooth ground for the fabric. The heavy fabric appears to be in layers, as the warp ends are crammed drawing three, four and up to seven ends per dent for the Tipara, Chaupara up to Satpara respectively.

Zari is generally of two types Badla and Kala batto. Badla Zari was made of flattened gold or silver wire with the ancient method of making zari from pure metal without any core thread. This accounted for its peculiar stiffness. Sometimes cracks would develop in the metal during the process of weaving which resulted in the loss of its natural luster and smoothness. Therefore, weaving with Badla Zari was difficult and required great skill. Often a touch of Badla was given to floral motives to enhance the beauty. This type of zari has mostly gone out of favor amongst the contemporary weavers and they mostly depend on polyester or pure silk as a substitute.

Silk brocade of Banaras, Ahmedabad and Surat were well known in the 17th century. While Banaras continues to be a centre of production of silk brocades, Ahmedabad and Surat have practically nothing to show today. On the other hand, silk brocade weaving has gained ground in the south of India.

Pot-thans

These are called katan (a thread prepared by twisting a different number of silk filaments) brocades. Pot-thans are lighter in textures (lower thread count) than kinkhwabs but closely woven in silk and all or certain portions of the pattern are in gold or silver zaris. These fabrics are mostly used for making expensive garments and saris. Very often the satin ground weave is particularly used for garments fabrics. These fabrics are characterized by their jals which are normally made out of silk and tilla.

Mashru

The cloth was distinguished by its butis woven in circular shapes that gave an impression of ashrafis (gold coins). The ashrafis were usually woven in gold zari.

This is a mixed fabric with a woven stripe or zigzag pattern. The warp and weft used were of two different materials (silk and cotton, cotton and linen, silk and wool or wool and cotton) in different colours. It was used mostly for lower garments such as trousers, the lining of the heavy brocade garments or as furnishing.[7]

Gul Badan (the literal meaning of which is ‘flower like body’) was a known variety of mushru (cotton and silk) popular in the late 19th century. Sangi, Ganta, Ilaycha were types of mashru too. These were popular since ancient times and were known to be woven at all leading silk centres. One reason for their popularity was Islam. Since Islam does not allow men to wear pure silk, mashru (literally meaning permitted) became very popular amongst Muslims.

Himru or Amru

A type of Indian brocade is the Himru, a specialty of Hyderabad and Aurangabad, which is woven from silk and zari on silk to produce variegated designs, woven on the principle of extra weft. Himru can be very pretty with a pseudo-rich effect in general. It continued to be in popular demand on the account of its low price as compared to the pure silk brocades. Another point in its favor is that it can be woven very fine so as to give it a soft feel, thus making it more suitable as a fabric for personal wear than the true brocade.

The cloth is distinguished by its intricate char-khana (four squares) jal. These are woven like kinkhwabs, but without the use of kala battu (zari) instead badla zari is used.

Kinkhwabs

Kinkhwabs fabrics of India have earned a great reputation for their craftsmanship and grandeur. By and large, still continue to do so, even in the face of fierce competition from other types of woven and printed fabrics.

Kinkhwabs today are typically ornate, jacquard-woven fabrics. The pattern is usually emphasized by contrasting surfaces and colours and appears on the face of the fabric, which is distinguished easily from the back. Uses include apparel, draperies, upholstery and other decorative purposes.

Gyasar

Gyasar is a silk fabric of a kinkhwab structure with ground, in which the gold thread is profusely used with Tibetan designs. The fabric is especially popular with Tibetans and used extensively in their dresses as well as in decorative hangings, prayer mats, etc.

Gyanta

Gyanta is a silk fabric of kinkhwab structure of a satin body with or without the use of gold thread. These sometimes have a tantric design (which is also known as tchingo) of human heads with three eyes woven in gold and silver threads on a black satin ground.

Jamawar

"Jama" means robe and "war" is yard. The base of the jamawar is mostly silk, with perhaps an addition of a little polyester. The brocaded parts are woven in similar threads of silk and polyester. Most of the designs seen today are floral, with the kairy (i.e. the paisley) as the predominant motif.

Today, the best jamawar is woven in Varanasi. This fabric is widely used in the country for bridal and special occasion outfits. The texture and weave of patterns is such that the fabric often gets caught when rubbed against rough surfaces (metallic embroidery, jewellery etc.) it must therefore be handled delicately when worn.

Origin

Traders introduced this Chinese silk cloth to India, mainly from Samarkand and Bukhara and it gained immense popularity among the royalty and the aristocracy. King and nobles bought the woven fabric by the yard, wearing it as a gown or using it as a wrap or shawl. Jamawar weaving centres in India developed in the holy cities and the trade centres. The most well known jamawar weaving centres were in Assam, Gujrat, Malwa and South India.

Due to its rich and fine raw materials, the rich and powerful merchants used jamawar and noblemen of the time, who could not only afford it but could even commission the weavers to make the fabric for them, as in the case of the Mughals. Emperor Akbar was one of its greatest patrons. He brought many weavers from East Turkestan to Kashmir.

One of the main reasons for the diversity in the designs of the jamawar cloth was the migratory nature of its weavers. Ideas from almost all parts of the world influenced these designs.

The Indian motifs were greatly influenced by nature like the sun, moon, stars, rivers, trees, flowers, birds etc. The figural and geometrical motifs such as trees, lotus flower, bulls, horses, lions, elephants, peacocks, swans, eagles, the sun, stars, diagonal or zigzag lines, squares, round shapes, etc. can be traced through the entire history of jamawar and are still being used but in a rather different form in terms of intricacy and compositions, thus creating new patterns.

Indian weaver predominantly used a wide variety of classical motifs such as the swan (hamsa), the lotus (kamala), the tree of life (kulpa, vriksha), the vase of plenty (purna, kumbha), the elephant (hathi), the lion (simha), flowing floral creepers (lata patra), peacocks (mayur) and many more. Legendary creatures such as winged lions, centaurs, griffins, decorative of ferocious animals, animals formally in profile or with turned heads, animals with human figures in combat or represented in roundels were also commonly used motifs. These motifs have remained in existence for more than two thousand years. However, new patterns have consistently been introduced; sometimes some of these are even an amalgamation of the existing patterns. Such attempts at evolving new designs were particularly noticeable from the 10th century onwards, when patterns were altered to meet the specific demands of the Muslim rulers.

The bull or the swan, arranged between vertical and diagonal stripes can still be found in the silk jamawar saris of India. Patterns with small flowers and two-coloured squares (chess board design) are seen, used both as a garment and as furnishing material – bed spreads with same kind of pattern are still woven in some parts of Gujarat.

Jamawar dating back to the Mughal era however contained big, bold and realistic patterns, which were rather simple with ample space between the motifs. The designs stood out prominently against the background of the cloth.

Complex patterns were developed only when additional decorative elements were included in the basic pattern. During later periods, the gap between the motifs was also filled with smaller motifs or geometrical forms. The iris and narcissus flowers became the most celebrated motifs of this era and were combined with tulips, poppies, primulas, roses and lilies. A lot of figurative motifs were also used in the Mughal era such as deer, horses, butterflies, peacocks and insects. The Mughal kings played a vital role in the enhancement of jamawar by putting their inspirations into the cloth's designing and visiting the weavers on a regular basis to supervise its making. Shining, decorative pallus were jals were the main designs of this time. The borders were usually woven with silk and zari.

After the Mughal period, the figurative motifs were discouraged by the Muslims and more floral and paisleys were introduced. However, inspiration was taken from these figurative motives and put into designs as in the case of using only the peacock feathers instead of the complete figure.

Another big change was brought about in 1985, where the source of inspiration was the Chinese Shanghai cloth. The patterns of the Chinese Shanghai were amended in accordance to the weave construction of the jamawar cloth and introduced in the cloth. This proved to be a very successful change and is still appreciated by many.

In recent years, the Indian government has attempted a modest revival of this art by setting up a shawl-weaving centre at Kanihama in Kashmir. Efforts to revive this art have also been made by bringing in innovations like the creation of jamawar saris by craftsmen in Varanasi. Each sari is a shimmering tapestry of intricate design, in colours that range from the traditionally deep, rich shades to delicate pastels. A minimum of four months of patient effort goes into the creation of each jamawar sari. Many of the jamawar saris now have matching silk shawls attached to them, creating elegant ensembles fit for royalty.

Weaving of jamawar in Pakistan

Pakistan makes its own yarn from the imported cocoons that come from China. The yarn is cultivated in areas like Orangi and Shershah in Karachi which is then sold to the weavers. The pure silk yarn, before it can be used, has to undergo treatment such as bleaching or washing (in soap) and then dyeing. In its raw state, the silk is hard due to the sericlan; therefore it has to be removed. A single filament of the silk yarn is not strong enough to be woven on its own; therefore, it needs to be twisted in order to give it strength and hold.

A specific person who is called a naqsha-bandh first draws the patterns or designs on paper which are then transferred on a graph paper on a comparatively much bigger scale. Every square in the graph signifies a specific number of threads on the loom. The unfinished, rough ideas and sketches are provided to these naqsha-bandhs by the wholesalers and are thus plotted on the graph. The use of various threads in the pattern such as zari, resham, polyester, etc. are separated on the graph with the help of colours indicated on a key chart. The wholesalers later decide the main colours and this information are forwarded to the weavers. The naqsha-bandhs do not have say in the designing of the motifs and patterns. They do what they are told to do.

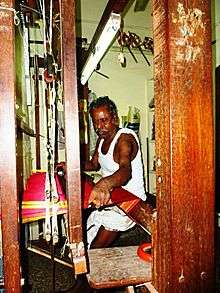

In this way, the pattern or motif is drawn on the graph paper to provide the weaver with the exact picture of each thread making up the design in the process of weaving. The designs and patterns are then transferred from the graph paper on a wooden frame and are referred to as the naqsha. The naqsha that is made with cotton threads is a smaller sample of the actual design, which is to be woven on the loom. The warp is then taken for the weaving process, which is carried out, on various looms such as the pit loom, jacquard loom and power loom. There is a vast difference between the outputs of the three types of looms. The power looms cannot match the intricacy that can be achieved using the pit or jacquard loom. This is the reason for the far superior workmanship that can be found in the earlier designs dating back to the Mughal era.

Significant regions of silk

Assam silk

Assam silk denotes the three major types of indigenous wild silks produced in Assam—golden muga, white pat and warm eri silk. The Assam silk industry, now centred in Sualkuchi, is a labour-intensive industry. It's registered trademark is SUALKUCHI'S.[8]

In 2015, Adarsh Gupta K of Nagaraju's research team at Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics, Hyderabad, India discovered the complete sequence and the protein structure of muga silk fibroin and published it in Nature Scientific Reports [9]

Mysore

Karnataka produces 9,000 metric tons of mulberry silk of a total of 14,000 metric tons produced in the country, thus contributing to nearly 70% of the country's total mulberry silk. In Karnataka, silk is mainly grown in the Mysore district. In the second half of the 20th century, it revived and the Mysore State became the top multivoltine silk producer in India.[10]

Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram is located very close to Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu. From the past Kanchipuram silk sarees stand out from others due to its intricate weaving patterns and the quality of the silk itself. Kanchipuram silk sarees are large and heavy owing to the zari work on the saree. Kanchipuram attracts large number of people, both from India and abroad, who come specifically to buy the silk sarees. Most of the sarees are still hand woven by workers in the weaving unit. More than 5000 families still indulge in silk weaving.

In 2008 the noted film director Priyadarshan made a Tamil film Kanchivaram about the silk weavers of the town during the pre-independence period. The film won the Best Film Award at the annual National Film Awards.

Banarasi

A Banarasi sari is a sari made in Varanasi, a city which is also called Benares or Banaras. The saris are among the finest saris in India and are known for their gold and silver brocade or zari, fine silk and opulent embroidery. The saris are made of finely woven silk and are decorated with intricate design, and, because of these engravings, are relatively heavy.

Their special characteristics are Mughal inspired designs such as intricate intertwining floral and foliate motifs, kalga and bel, a string of upright leaves called jhallar at the outer, edge of border is a characteristic of these saris. Other features are gold work, compact weaving, figures with small details, metallic visual effects, pallus, jal (a net like pattern), and mina work.

The saris are often part of an Indian bride's trousseau.

Depending on the intricacy of its designs and patterns, a sari can take from 15 days to a month and sometimes up to six months to complete. Banarasi saris are mostly worn by Indian women on important occasions such as when attending a wedding and are expected to be complemented by the woman's best jewellery. it is from Banarasi sari.

Origin

%2C_silk_and_gold-wrapped_silk_yarn_with_supplementary_weft_brocade.jpg)

Banaras (Varanasi) is situated on the Calcutta / Delhi rail route 760 km (470 mi) from Calcutta. It has always been a big textile centre of silk weaving. European travellers like Marco Polo (1271–1295) and Tavernier (1665) do not mention the manufacture of brocades in Banaras. Ralph Fitch (1583–91) describes Banaras as a thriving sector of the cotton textile industry. The earliest mention of the brocade and Zari textiles of Banaras is found in the 19th century. With the migration of silk weavers from Gujarat during the famine of 1603, it is likely that silk brocade weaving started in Banaras in the 17th century and developed in excellence during the 18th and 19th century.

Distinguishing characteristics

The following are considered to be the main characteristics of the brocade fabrics of Banaras.

- heavy gold work

- compact weaving

- figures have small details

- metallic visual effects

- pallus

- jal (a net like pattern)

- mina work

Banarasi brocade produced two sub-variants from its original structure namely:

- Katan

- Tanchoi

Katan

Katan is a thread, prepared by twisting a different number of silk filaments according to requirement gives a firm structure to the background fabric. Katan is a plain woven fabric with pure silk threads. It consists of two threads twisted together and is mostly used for the warp of light fabrics.

Katan can be further classified into the following:

- Katan Butidar: Fabric with Katan warp and weft with butis (designs and patterns) in gold or resham (untwisted silk).

- Katan Butidar Mina: Katan Butidar with Mina work (design made out of zari thread) in butis.

- Katan Butidar Paga Saree: Saree with Katan warp, resham weft, small butis all over body, closely spaced (about 10 cm (4") apart), about 5 cm (2") wide border and 30–55 cm (12-22") wide pallu.

- Katan Brocade: This is a fabric with Katan warp and Katan weft with figures in gold thread with or without mina, with the traditional styles being ‘katrawan’, ‘kardhwan’ and ‘Fekva’.

- Katrawan: A technique or design in which the floating portions of the extra weft (laid from selvege to selvege) at the back of the fabric is cut.

- Kardhwan

- Fekva

- Jangla: Plain fabric of Katan warp and Katan weft, with all-over floral designs in an extra weft of either silk or zari.

- Katan Katrawan Mina: A fabric in Katrawan style with Mina.

These days the currently used designs and motifs involving Katan are:

- Katan Jal Set: Over the years with minor innovations and influences from other materials, Jangla is now known as ‘Katan Jal Set’.

- Katan Buti Zari Resham: Katan Butidar has evolved over time to become Katan Buti Zari Resham.

- Katan Stripe and Katan Check are also popular variants found in the markets.

Tanchoi

Plain woven body with one color extra weft, one color weft and one color warp. Relative to the jamawar, it is lighter and softer. Tanchoi could be further classified into the following:

Satan Tanchoi is the satin weave (four ends and eight picks or five ends and five picks satin) with the warp in one color and the weft in one or more colors. The extra weft in the design may also be used as body weft.

- Satan Jari Tanchoi: Satan Tanchoi with weft in the order of one silk and one gold thread (Jari), or two silk (double) and one gold thread.

- Satan Jari Katrawan Tanchoi: Satan Jari tanchoi in which the floating, extra weft, gold thread at the back is cut and removed.

- Atlas: Atlas is a pure satin body. Relative to other fabrics, Atlas is thicker, heavier and is shinier than other fabrics because of the extra use of zari. It is also known as gilt, because it is even shinier than the katan.

- Mushabbar: The cloth is distinguished by its jal woven as bushes and branches of trees. The normal association with the design was that of a jungle.

Karachi

Contemporary designs and motifs

The jamawar weaving technique is often defined as ‘embroidery weaving’ or ‘loom embroidery’. This technique can also be applied on other fibres but jamawar is generally restricted to rich silk threads. Currently, any of the major textile fibres may be used in a wide range of quality and price.

Currently, two kinds of kinkhwab (jamawar) are available in the markets. Mughal jamawar and self jamawar. Mughal jamawar has a distinct characteristic of the use of gold and silver zari with silk, the use of gold zari with silver zari and the use of zari with polyester. Self jamawar does not involve zari and basically is either silk on silk or silk with polyester.

Further reading

- The Making Of A Hand-Woven Kanjivaram Silk Saree - Read how Kanjivaram Silk saree is being made.

- History of Kanchipuram Silk Sarees - Read more on the history of Kanchipuram Silk sarees.

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2016-03-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Silk city to come up near B'lore". deccanherald.com. 17 October 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- "Tamil Nadu's first automatic silk reeling unit opened". The Hindu. 24 August 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- Good, I.L.; Kenoyer, J.M.; Meadow, R.H. (2009). "New evidence for early silk in the Indus civilization". Archaeometry (Submitted manuscript). 50 (3): 457. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2008.00454.x.

- Ball, Philip (19 February 2009). "Rethinking silk's origins". Nature. 457 (7232): 945. doi:10.1038/457945a. PMID 19238684.

- "Blue Silk Brocade 473 Fabric | NY Designer Fabrics". www.nydesignerfabrics.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- York, Neil (2016). Silk Fabrics from the Orient (First ed.). USA: Lulu. ISBN 978-1-365-31798-9.

- "From 2016, Sualkuchi textile products has a trademark Sualkuchi's in proprietorship of Sualkuchi Tat Silpa Unnayan Samity". Intellectual Property India. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10.

- Adarsh Gupta. K. "Molecular architecture of silk fibroin of Indian golden silkmoth, Antheraea assama". Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- R.k.datta (2007). Global Silk Industry: A Complete Source Book. APH Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-8131300879. Retrieved January 22, 2013.