Japonic languages

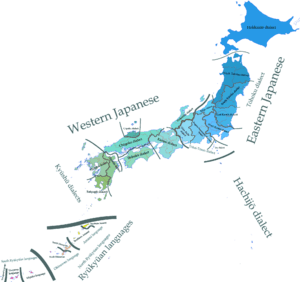

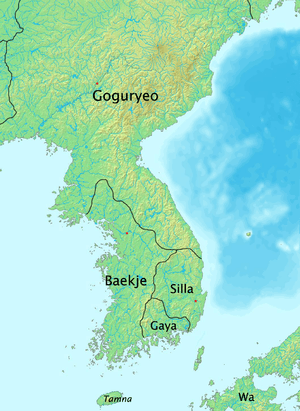

The Japonic, or Japanese–Ryukyuan, language family includes the Japanese language, spoken in the main islands of Japan, and the Ryukyuan languages, spoken in the Ryukyu Islands. The family is universally accepted by linguists, and significant progress has been made in reconstructing the proto-language.[1] The reconstruction implies a split between all dialects of Japanese and all Ryukyuan varieties, probably before the 7th century. The Hachijō language, spoken on the Izu Islands, is also included, but its position within the family is unclear. There is also some fragmentary evidence suggesting that Japonic languages may once have been spoken in central and southern parts of the Korean peninsula (see Peninsular Japonic).

| Japonic | |

|---|---|

| Japanese–Ryukyuan | |

| Geographic distribution | Japan, possibly formerly on the Korean Peninsula |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Japonic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | jpx |

| Glottolog | japo1237 |

Japonic languages and dialects | |

Possible genetic relationships with many other language families have been proposed, most systematically with Korean, but none have been conclusively demonstrated.

Classification

The extant Japonic languages comprise two well-defined branches: Japanese and Ryukyuan.[2] An alternative classification, based mainly on the development of the pitch accent, groups the highly divergent Kagoshima dialects of southwestern Kyushu with Ryukyuan in a Southwestern branch.[3]

Most scholars believe that Japonic was brought to northern Kyushu from the Korean peninsula around 700 to 300 BC by wet-rice farmers of the Yayoi culture and spread throughout the Japanese archipelago, replacing indigenous languages.[4][5] Somewhat later, Japonic languages also spread southward to the Ryukyu Islands.[4] There is fragmentary placename evidence that now-extinct Japonic languages were still spoken in central and southern parts of the Korean peninsula several centuries later.[6][7]

Japanese

Japanese is the national language of Japan, where it is spoken by about 126 million people. The oldest attestation is Old Japanese, which was recorded by Chinese characters in the 7th and 8th centuries.[8]

It differed from Modern Japanese in having a simple (C)V syllable structure and avoiding vowel sequences.[9] The script also distinguished eight vowels (or diphthongs), with two each corresponding to modern i, e and o.[10] Most of the texts reflect the speech of the area around Nara, the capital, but over 300 poems were written in eastern dialects of Old Japanese.[11][12]

The language experienced a massive influx of Sino-Japanese vocabulary after the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century and peaking with the wholesale importation of Chinese culture in the 8th and the 9th centuries.[13] The loanwords now account for about half the lexicon.[14] They also affected the sound system of the language by adding compound vowels, syllable-final nasals, and geminate consonants, which became separate morae.[15]

Modern mainland Japanese dialects, spoken on Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido, are generally grouped as follows:[16]

- Eastern Japanese, including most dialects from Nagoya east, including the modern standard Tokyo dialect.

- Western Japanese, including most dialects west of Nagoya, including the Kyoto dialect.

- Kyushu dialects, spoken on the island of Kyushu, including the Kagoshima dialect/Satsugū dialect, spoken in Kagoshima Prefecture in southern Kyushu.

The early capitals of Nara and Kyoto lay within the western area, and their Kansai dialect retained its prestige and influence long after the capital was moved to Edo (modern Tokyo) in 1603. Indeed, the Tokyo dialect has several western features not found in other eastern dialects.[17]

The Hachijō language, spoken on Hachijō-jima and the Daitō Islands, including Aogashima, is highly divergent and varied. It has a mix of conservative features inherited from Eastern Old Japanese and influences from modern Japanese, making it difficult to classify.[18][19][20] Hachijō is an endangered language, with a small population of elderly speakers.[5]

Ryukyuan

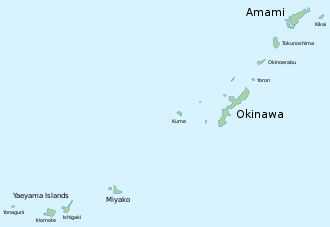

The Ryukyuan languages were originally and traditionally spoken throughout the Ryukyu Islands, an island arc stretching between the southern Japanese island of Kyushu and the island of Taiwan. Most of them are considered "definitely" or "critically endangered" because of the spread of mainland Japanese.[21]

Since Old Japanese displayed several innovations that are not shared with Ryukyuan, the two branches must have separated before the 7th century.[22] The move from Kyushu to the Ryukyus may have occurred later and possibly coincided with the rapid expansion of the agricultural Gusuku culture in the 10th and 11th centuries.[23] Such a date would explain the presence in Proto-Ryukyuan of Sino-Japanese vocabulary borrowed from Early Middle Japanese.[24] After the migration to the Ryukyus, there was limited influence from mainland Japan until the conquest of the Ryukyu Kingdom by the Satsuma Domain in 1609.[25]

Ryukyuan varieties are considered dialects of Japanese in Japan but have little intelligibility with Japanese or even among one another.[26] They are divided into northern and southern groups, corresponding to the physical division of the chain by the 250 km-wide Miyako Strait.[21]

Northern Ryukyuan languages are spoken in the northern part of the chain, including the major Amami and Okinawa Islands. They form a single dialect continuum, with mutual unintelligibility between widely-separated varieties.[27] The major varieties are, from northeast to southwest:[28]

- Kikai, on the island of Kikaijima.

- Northern Amami Ōshima, spoken in most of Amami Ōshima

- Southern Amami Ōshima, spoken in Setouchi on the southern end of Amami Ōshima.

- Tokunoshima, on the island of Tokunoshima.

- Okinoerabu, on the island of Okinoerabujima

- Yoron, on the island of Yoronjima.

- Northern Okinawan, spoken in the northern part of Okinawa Island, including the cities of Nakijin and Nago.

- (Central) Okinawan, spoken in the central and southern parts of Okinawa Island, and neighboring islands. The prestige dialect is spoken in Naha, and the former city of Shuri. The Shuri dialect was the lingua franca of the Ryukyuan Kingdom, and was first recorded in the 16th century, particularly in the Omoro Sōshi anthology.[21][29]

There is no agreement on the subgrouping of the varieties. One proposal has three subgroups, with the central "Kunigami" branch comprising varieties from Southern Amami to Northern Okinawan, based on similar vowel systems and patterns of lenition of stops. Pellard suggests a binary division based on shared innovations, with an Amami group including the varieties from Kikai to Yoron, and an Okinawa group comprising the varieties of Okinawa and smaller islands to its west.[30]

Southern Ryukyuan languages are spoken in the southern part of the chain, the Sakishima Islands. They comprise three distinct dialect continua:[27]

- Miyako is spoken in the Miyako Islands, with dialects on Irabu and Tarama.

- Yaeyama is spoken in the Yaeyama Islands (except Yonaguni), with dialects on each island, but primarily Ishigaki Island, Iriomote Island, and Taketomi Island.

- Yonaguni, spoken on Yonaguni Island, is phonologically distinct but lexically closer to other Yaeyama varieties.[31]

The southern Ryukyus were settled by Japonic-speakers from the northern Ryukyus in the 13th century, leaving no linguistic trace of the indigenous inhabitants of the islands.[25]

Peninsular Japonic

There is fragmentary evidence suggesting that now-extinct Japonic languages were spoken in the central and southern parts of the Korean peninsula:[6][7][5]

- Chapter 37 of the Samguk sagi (compiled in 1145) contains a list of pronunciations and meanings of placenames in the former kingdom of Goguryeo. As the pronunciations are given using Chinese characters, they are difficult to interpret, but several of those from central Korea, in the area south of the Han River captured from Baekje in the 5th century, seem to correspond to Japonic words.[32][5] Scholars differ on whether they represent the language of Goguryeo or the people that it conquered.[5][33]

- The Silla placenames, listed in Chapter 34 of the Samguk sagi, are not glossed, but many of them can be explained as Japonic words.[5]

- A single word is explicitly attributed to the language of the southern Gaya confederacy, in Chapter 44 of the Samguk sagi. It is a word for 'gate' and appears in a similar form to the Old Japanese word to2, with the same meaning.[34][35]

- Alexander Vovin suggests that the ancient name for the kingdom of Tamna on Jeju Island, tammura, may have a Japonic etymology tani mura 'valley settlement' or tami mura 'people's settlement'.[36]

Vovin calls these languages Peninsular Japonic and groups Japanese and Ryukyuan as Insular Japonic.[5]

Proposed external relationships

According to Shirō Hattori, more attempts have been made to link Japanese with other language families than for any other language.[37] None of the attempts has succeeded in demonstrating a common descent for Japonic and any other language family.[5]

The most systematic comparisons have involved Korean, which has a very similar grammatical structure to Japanese. Samuel Elmo Martin, John Whitman, and others have proposed hundreds of possible cognates, with sound correspondences.[5][38][39] However, Alexander Vovin points out that Old Japanese contains several pairs of words of similar meaning in which one word matches a Korean form, and the other is also found in Ryukyuan and Eastern Old Japanese.[40] He thus suggests that to eliminate early loans from Korean, Old Japanese morphemes should not be assigned a Japonic origin unless they are also attested in Southern Ryukyuan or Eastern Old Japanese.[41] That procedure leaves fewer than a dozen possible cognates, which may have been borrowed by Korean from Peninsular Japonic.[42]

Typology

Most Japonic languages have voicing opposition for obstruents, with exceptions such as the Miyako dialect of Ōgami.[43] Glottalized consonants are common in North Ryukyuan languages but are rarer in South Ryukyuan.[44][31] Proto-Japonic had only voiceless obstruents, like Ainu and proto-Korean. Japonic languages also resemble Ainu and modern Korean in having a single liquid consonant phoneme.[45] A five-vowel system like Standard Japanese /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/ is common, but some Ryukyuan languages also have central vowels /ə/ and /ɨ/, and Yonaguni has only /a/, /i/, and /u/.[21][46]

In most Japonic languages, speech rhythm is based on a subsyllabic unit, the mora.[47] Each syllable has a basic mora of the form (C)V but a nasal coda, geminate consonant, or lengthened vowel counts as an additional mora.[48] However, some dialects in northern Honshu or southern Kyushu have syllable-based rhythm.[49]

Like Ainu, Middle Korean, and some modern Korean dialects, most Japonic varieties have a lexical pitch accent, which governs whether the moras of a word are pronounced high or low, but it follows widely-different patterns.[45][50] In Tokyo-type systems, the basic pitch of a word is high, with an accent (if present) marking the position of a drop to low pitch.[51] In Kyushu dialects, the basic pitch is low, with accented syllables given high pitch, and in Kyoto-type systems, both types are used.[52]

Japonic languages, again like Ainu and Korean, are left-branching (or head-final), with a basic subject–object–verb word order, modifiers before nouns, and postpositions.[53][54] There is a clear distinction between verbs, which have extensive infectional morphology, and nominals, which have no inflection.[55]

Proto-Japonic

| Proto-Japonic | |

|---|---|

| Proto-Japanese–Ryukyuan | |

| Reconstruction of | Japonic |

The proto-language of the family has been reconstructed by using a combination of internal reconstruction from Old Japanese and by applying the comparative method to Old Japanese (including eastern dialects) and Ryukyuan.[56] The major reconstructions of the 20th century were produced by Samuel Elmo Martin and Shirō Hattori.[56][57]

Phonology

Proto-Japonic words are generally polysyllabic, with syllables having the form (C)V. The following proto-Japonic consonant inventory is generally agreed upon, except for the values of *w and *j (see below):[58]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | *m | *n | ||

| Stop | *p | *t | *k | |

| Fricative | *s | |||

| Approximant | *w | *j | ||

| Liquid | *r |

It is agreed that the Old Japanese voiced consonants b, d, z and g, which never occurred word-initially, are derived from clusters of nasals and voiceless consonants.[59] In most cases, the two consonants were brought together by loss of an intervening vowel. A few words display no evidence for a former vowel, and scholars reconstruct a syllable-final nasal of indeterminate place preceding the voiceless obstruent, as in *tunpu > tubu 'grain', *pinsa > piza 'knee'. These nasals are unrelated to the moraic nasal of later forms of Japonic, which derive from contractions or borrowings from other languages such as Chinese.[60]

The other Old Japanese consonants are projected back to Proto-Japonic except that authors disagree on whether the sources of Old Japanese w and y should be reconstructed as glides *w and *j or as voiced stops *b and *d respectively, based on Ryukyuan reflexes:[58]

- Southern Ryukyuan varieties have /b/ corresponding to Old Japanese w, e.g. ba 'I' and bata 'stomach' corresponding to Old Japanese wa and wata.[61] Two dialects spoken around Toyama Bay on the west coast of Honshu also have /b/ corresponding to initial /w/ in other Japanese dialects.[62]

- Yonaguni, at the far end of the Ryukyu island chain, has /d/ in words where Old Japanese has y, e.g. da 'house', du 'hot water' and dama 'mountain' corresponding to Old Japanese ya, yu and yama.[61]

Many authors, including advocates of a genetic relationship with Korean and other northeast-Asian languages, argue that Southern Ryukyuan initial /b/ and Yonaguni /d/ are retentions of Proto-Japonic voiced stops *b and *d that became /w/ and /j/ elsewhere through a process of lenition.[63] However, many linguists, especially in Japan, prefer the opposite hypothesis, namely that Southern Ryukyuan initial /b/ and Yonaguni /d/ are derived from local innovations in which Proto-Japonic *w and *j underwent fortition.[64] The case for lenition of *d- > j- is substantially weaker, with the fortition hypothesis supported by Sino-Japonic words with Middle Chinese initials in *j also having reflexes of initial /d/ in Yonaguni, such as dasai from Middle Chinese 野菜 *jia-tsʰʌi.[65] Further evidence is provided by an entry in the late-15th-century Korean annal Seongjong Taewang Sillok recording the local name of the island of Yonaguni in Idu script as 閏伊是麼, which has the Middle Korean reading zjuni sima, with sima glossed in the text as the Japonic word for 'island'. That is direct evidence of an intermediate stage of the fortition *j- > *z- > d-, leading to the modern name /dunaŋ/ 'Yonaguni'.[66]

Most authors accept six Proto-Japonic vowels:[67]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | *i | *u | |

| Mid | *e | *ə | *o |

| Open | *a |

The vowels *i, *u, *ə and *a have been obtained by internal reconstruction from Old Japanese, with the other Old Japanese vowels derived from vowel clusters.[68][69] The mid vowels *e and *o are required to account for Ryukyuan correspondences.[70] In Old Japanese, they were raised to i and u respectively except word-finally.[69][71] They have also left some traces in eastern Old Japanese dialects[72] and are also found in some early mokkan and in some modern Japanese dialects.[73]

| Proto-Japonic | Proto-Ryukyuan | Old Japanese |

|---|---|---|

| *i | *i | i1 |

| *e | *e | i1 (e1) |

| *u | *u | u |

| *o | *o | u (o1) |

| *ə | o2 | |

| *a | *a | a |

The other vowels of Old Japanese are believed to derive from sequences of vowels in Proto-Japanese, with different reflexes in Ryukyuan and Eastern Old Japanese:[74][75]

| Proto-Japonic | Proto-Ryukyuan | Old Japanese | Eastern Old Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|

| *ui | *i | i2 | i |

| *əi | *e | i2 (e2) | |

| *ai | e2 | e | |

| *iə | e1 | ||

| *ia | a | ||

| *au | *o | o1 | o1 |

| *ua |

In most cases, Proto-Japonic *əi corresponds to Old Japanese i2. Proto-Japonic *əi is reconstructed for Old Japanese e2 in the few cases that it alternates with o2 (< *ə). Some authors propose a high central vowel *ɨ to account for these alternations, but there is no evidence for it in Ryukyuan or Eastern Old Japanese.[76][77] The reasons for the alternate reflex e2 are unclear, but its occurrences seem to be limited to specific single-mora roots such as se~so2 'back', me2~mo2 'seaweed', and possibly ye~yo2 'handle'.

The Japanese pitch accent is usually not recorded in the Old Japanese script.[78] The oldest description of the accent, in the 12th-century dictionary Ruiju Myōgishō, defined accent classes that generally account for correspondences between modern mainland Japanese dialects.[79] However, Ryukyuan languages share a set of accent classes that cut across them.[80] For example, for two-syllable words, the Ruiju Myōgishō defines five accent classes, which are reflected in different ways in the three major accent systems of mainland Japanese, here represented by Kyoto, Tokyo, and Kagoshima. In each case, the pattern of high and low pitches is shown across both syllables and a following neutral particle. Ryukyuan languages, here represented by Kametsu (the prestige variety of the Tokunoshima language), show a three-way division, which partially cuts across the five mainland classes.

| Class | Kyoto | Tokyo | Kagoshima | Kametsu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | HH-H | LH-H | LH-L | LH-H | |

| 2.2 | HL-L | LH-L | |||

| 2.3 | LL-H | (a) HL-L | (b) LH-L | ||

| 2.4 | LL-H | HL-L | |||

| 2.5 | LH-L | ||||

In some Ryukyuan dialects, including Shuri, subclass (a) is marked by a long vowel in the first syllable instead of a distinct pitch pattern, which led Hattori to suggest that the original distinction was one vowel length.[83]

Pronouns

The following personal pronouns can be reconstructed for Proto-Japonic, based on Old Japanese and Ryukyuan data.[84][85]

- *a(ra), *wa 'I' (singular)

- *wa(ja) 'we' (plural)

- *u, *o 'you' (singular)

- *uja, *ura 'you' (plural)

The form *na, which may have been borrowed from Koreanic, yielded an ambivalent personal pronoun in Japanese, a second-person pronoun in Northern Ryukyuan, and a reflexive pronoun in Southern Ryukyuan.[86][87]

The following interrogative pronouns can be reconstructed for Proto-Japonic.

- *ta 'who'

- *na 'what'

- *etu 'when'

- *e(ntu)ku 'where'

- *eka 'how'

The question particle was *ka.

The following demonstrative pronouns can be reconstructed for Proto-Japonic.[88][89]

- *i 'this' (proximal)

- *sə 'that' (distal)

The daughter languages later innovated a mesial, causing a split within the demonstrative system. Eventually, proximal *i was lost and replaced by *kə. Distal *sə eventually became mesial, and *ka, which was apophonic to the newly-replaced proximal, became the distal pronoun in all modern languages. Proto-Ryukyuan later replaced *sə with *o, which was unrelated.[90]

Vocabulary

The Proto-Japonic numerals are:

| Proto-Japonic[86] | Mainland | Ryukyuan | Peninsular | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Japanese[91] | Shuri[92] | Hatoma[93] | Yonaguni[94] | Baekje[5] | ||

| 1 | *pitə | pi1to2 | tii | pusu | tʼu- | |

| 2 | *puta | puta | taa | huta | tʼa- | |

| 3 | *mit | mi1 | mii | mii | mii- | *mit |

| 4 | *jə | yo2 | juu | juu | duu- | |

| 5 | *itu | itu | ici | ici | ici- | *yuci |

| 6 | *mu(t) | mu | muu | muu | muu- | |

| 7 | *nana | nana | nana | nana | nana- | *nanən |

| 8 | *ja | ya | jaa | jaa | daa- | |

| 9 | *kəkənə | ko2ko2no2 | kukunu | kunu | kugunu- | |

| 10 | *təwə | to2wo | tuu | tuu | tuu | *tək |

References

- Shimabukuro (2007), p. 1.

- Tranter (2012), p. 3.

- Shimabukuro (2007), p. 2.

- Serafim (2008), p. 98.

- Vovin (2017).

- Vovin (2013), pp. 222–224.

- Sohn (1999), pp. 35–36.

- Frellesvig (2010), pp. 12–20.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 121.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 122.

- Miyake 2003, p. 159.

- Frellesvig 2010, pp. 23–24, 151–153.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 120–121.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 142–143.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 121–122, 167–170.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 187, 189.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 1999.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 207.

- Pellard (2015), pp. 16–17.

- Pellard (2018), p. 2.

- Shimoji (2012), p. 352.

- Pellard (2015), pp. 21–22.

- Pellard (2015), pp. 30–31.

- Pellard (2015), p. 23.

- Shimoji (2010), p. 4.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 191.

- Serafim (2008), p. 80.

- Grimes (2003), p. 335.

- Tranter (2012), p. 4.

- Pellard (2015), pp. 17–18.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 194.

- Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 37–43.

- Beckwith (2007), pp. 50–92.

- Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 46–47.

- Beckwith (2007), p. 40.

- Vovin (2013), pp. 236–237.

- Kindaichi (1978), p. 31.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 99–100.

- Sohn (1999), pp. 29–35.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 92–94.

- Vovin (2010), p. 6.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 237–240.

- Shimoji (2010), pp. 4–5.

- Shimoji (2010), p. 5.

- Tranter (2012), p. 7.

- Izuyama (2012), p. 413.

- Shimoji (2010), p. 6.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 158–159.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 160.

- Shimoji (2010), p. 7.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 180–181.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 182.

- Tranter (2012), p. 6.

- Shimoji (2010), p. 8.

- Shimoji (2010), pp. 9–10.

- Frellesvig & Whitman (2008), p. 1.

- Martin (1987).

- Frellesvig & Whitman (2008), p. 3.

- Whitman (2012), p. 27.

- Frellesvig (2010), p. 43.

- Shibatani 1990, p. 195.

- Vovin 2010, pp. 38–39.

- Vovin 2010, p. 40.

- Vovin 2010, pp. 36–37, 40.

- Vovin 2010, p. 41.

- Vovin 2010, pp. 43–44.

- Whitman (2012), p. 26.

- Martin (1987), p. 67.

- Frellesvig & Whitman (2008), p. 5.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 32–34.

- Frellesvig (2010), p. 47.

- Vovin (2010), p. 34.

- Osterkamp 2017, pp. 46–48.

- Pellard (2008), p. 136.

- Frellesvig (2010), p. 152.

- Frellesvig (2010), pp. 45–47.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 35–36.

- Miyake (2003), pp. 37–39.

- Shibatani (1990), pp. 210–212.

- Frellesvig & Whitman (2008), p. 8.

- Shibatani (1990), p. 212.

- Shimabukuro (2008), p. 128.

- Shimabukuro (2008), pp. 134–135.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 62–65.

- Thorpe (1983), pp. 218–223.

- Whitman (2012), p. 33.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 63–65.

- Vovin (2010), pp. 66–67.

- Frellesvig (2010), pp. 142–143.

- Vovin (2010), p. 71.

- Bentley (2012), p. 199.

- Shimoji (2012), p. 357.

- Lawrence (2012), p. 387.

- Izuyama (2012), p. 429.

Works cited

- Beckwith, Christopher (2007), Koguryo, the Language of Japan's Continental Relatives, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-16025-5.

- Bentley, John R. (2012), "Old Japanese", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 189–211, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010), A History of the Japanese Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65320-6.

- Frellesvig, Bjarne; Whitman, John (2008), "Introduction", in Frellesvig, Bjarne; Whitman, John (eds.), Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects, John Benjamins, pp. 1–9, ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1.

- Grimes, Barbara (2003), "Japanese – Language list", in Frawley, William (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Linguistics, 2 (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 335, ISBN 978-0-19-513977-8.

- Izuyama, Atsuko (2012), "Yonaguni", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 412–457, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- Kindaichi, Haruhiko (1978) [1957], The Japanese Language, Tuttle, ISBN 978-1-4629-0266-8.

- Lawrence, Wayne P. (2012), "Southern Ryukyuan", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 381–411, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011), A History of the Korean Language, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49448-9.

- Martin, Samuel Elmo (1987), The Japanese Language through Time, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-03729-6.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo (2003), Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction, London; New York: RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 978-0-415-30575-4.

- Osterkamp, Sven (2017), "A mokkan Perspective on Some Issues in Japanese Historical Phonology", in Vovin, Alexander; McClure, William (eds.), Studies in Japanese and Korean Historical and Theoretical Linguistics and Beyond, Languages of Asia, 16, Brill, pp. 45–55, doi:10.1163/9789004351134_006, ISBN 978-90-04-35085-4.

- Pellard, Thomas (2008), "Proto-Japonic *e and *o in Eastern Old Japanese", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 37 (2): 133–158, doi:10.1163/1960602808X00055.

- ——— (2015), "The linguistic archeology of the Ryukyu Islands", in Heinrich, Patrick; Miyara, Shinsho; Shimoji, Michinori (eds.), Handbook of the Ryukyuan languages: History, structure, and use, De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 13–37, doi:10.1515/9781614511151.13, ISBN 978-1-61451-161-8.

- ——— (2018), "The comparative study of the Japonic languages", Approaches to endangered languages in Japan and Northeast Asia: Description, documentation and revitalization, Tachikawa, Japan: National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics.

- Serafim, Leon A. (2008), "The uses of Ryukyuan in understanding Japanese language history", in Frellesvig, Bjarne; Whitman, John (eds.), Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects, John Benjamins, pp. 79–99, ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990), The Languages of Japan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36918-3

- Shimabukuro, Moriyo (2007), The Accentual History of the Japanese and Ryukyuan Languages: a Reconstruction, London: Global Oriental, ISBN 978-1-901903-63-8.

- ——— (2008), "A reconstruction of proto-Japanese accent for disyllabic nouns", in Frellesvig, Bjarne; Whitman, John (eds.), Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects, John Benjamins, pp. 126–139, ISBN 978-90-272-4809-1.

- Shimoji, Michinori (2010), "Ryukyuan languages: an introduction", in Shimoji, Michinori; Pellard, Thomas (eds.), An Introduction to Ryukyuan Languages (PDF), Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, pp. 1–13, ISBN 978-4-86337-072-2.

- ——— (2012), "Northern Ryukyuan", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 351–380, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (1999), The Korean Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36123-1.

- Thorpe, Maner Lawton (1983), Ryūkyūan language history (PhD thesis), University of Southern California.

- Tranter, Nicholas (2012), "Introduction: typology and area in Japan and Korea", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 3–23, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- Vovin, Alexander (2010), Korea-Japonica: A Re-Evaluation of a Common Genetic Origin, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3278-0, JSTOR j.ctt6wqz03.

- ——— (2013), "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean", Korean Linguistics, 15 (2): 222–240, doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.03vov.

- ——— (2017), "Origins of the Japanese Language", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.277, ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5.

- Whitman, John (2012), "The relationship between Japanese and Korean", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 24–38, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

Further reading

- Pellard, Thomas (2010), "Bjarke Frellesvig and John Whitman (2008). Proto-Japanese: Issues and Prospects", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 39 (1): 95–114, doi:10.1163/1960602810X00089.

- Vovin, Alexander (1994), "Long-distance Relationships, Reconstruction Methodology, and the Origins of Japanese", Diachronica, 11 (1): 95–114, doi:10.1075/dia.11.1.08vov.

External links

| Wiktionary has a list of forms reconstructed by Vovin at Appendix:Proto-Japanese Swadesh list |

- Databases of dialectical and historical linguistics at the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics