History of West Africa

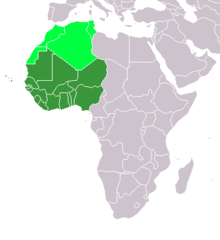

The history of West Africa has been commonly divided into its prehistory, the Iron Age in Africa, the major polities flourishing, the colonial period, and finally the post-independence era, in which the current nations were formed. West Africa is west of an imagined north-south axis lying close to 10° east longitude, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and Sahara Desert.

Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary West African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states. During the Holocene, sedentary farming began to develop in West Africa. The Iron industry, in both smelting and forging for tools and weapons, appeared in Sub-Saharan Africa by 1200 BCE, and by 400 BCE, contact had been made with the Mediterranean civilizations, and a regular trade included exporting gold, cotton, metal, and leather in exchange for copper, horses, salt, textiles, and beads. The Nok culture (1500 BCE - 200/300 BCE) would develop.[1] and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 AD, thus having lasted approximately 2,000 years.[2] The Serer people would construct the Senegambian stone circles (3rd century BCE - 16th century CE). The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of kingdoms or empires that were built on the sahel, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara. They controlled the trade routes across the desert, and were also quite decentralised, with member cities having a great deal of autonomy. The Ghana Empire may have been established as early as the 7th century CE. It was succeeded by the Sosso in 1230, the Mali Empire in the 13th century CE, and later by the Songhai and Sokoto Caliphate. There were also a number of forest empires and states in this time period.

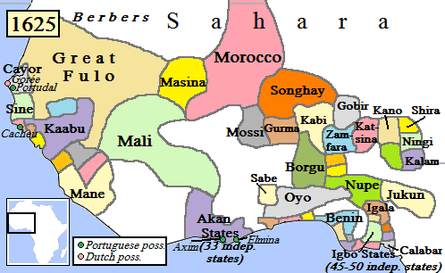

Following the collapse of the Songhai Empire, a number of smaller states arose across West Africa, including the Bambara Empire of Ségou, the lesser Bambara kingdom of Kaarta, the Fula/Malinké kingdom of Khasso (in present-day Mali's Kayes Region), and the Kénédougou Empire of Sikasso. European traders first became a force in the region in the 15th century. The transatlantic African slave trade resumed, with the Portuguese taking hundreds of captives back to their country for use as slaves; however, it would not begin on a grand scale until Christopher Columbus's voyage to the Americas and the subsequent demand for cheap colonial labour. As the demand for slaves increased, some African rulers sought to supply the demand by constant war against their neighbours, resulting in fresh captives. European, American and Haitian governments passed legislation prohibiting the Atlantic slave trade in the 19th century, though the last country to abolish the institution was Brazil in 1888.

In 1725, the cattle-herding Fulanis of Fouta Djallon launched the first major reformist jihad of the region, overthrowing the local animist, Mande-speaking elites and attempting to somewhat democratise their society. At the same time, the Europeans started to travel into the interior of Africa to trade and explore. Mungo Park (1771–1806) made the first serious expedition into the region's interior, tracing the Niger River as far as Timbuktu. French armies followed not long after. In the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s the Europeans started to colonise the inland of West Africa, they had previously mostly controlled trading ports along the coasts and rivers. Following World War II, campaigns for independence sprung up across West Africa, most notably in Ghana under the Pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972). After a decade of protests, riots and clashes, French West Africa voted for autonomy in a 1958 referendum, dividing into the states of today; most of the British colonies gained autonomy the following decade. Since independence, West Africa has suffered from the same problems as much of the African continent, particularly dictatorships, political corruption and military coups; it has also seen bloody civil wars. The development of oil and mineral wealth has seen the steady modernization of some countries since the early 2000s, though inequality persists.

Geographic background

West Africa is west of an imagined north-south axis lying close to 10° east longitude.[3] The Atlantic Ocean forms the western and southern borders of the West African region.[3] The northern border is the Sahara Desert, with the Ranishanu Bend generally considered the northernmost part of the region.[4] The eastern border is less precise, with some placing it at the Benue Trough, and others on a line running from Mount Cameroon to Lake Chad.

The area north of West Africa is primarily desert containing the Western Sahara. Ancient West Africa included the Sahara, which became a desert approximately 3000 BCE.[5] During the last glacial period, the Sahara, extending south far beyond the boundaries that now exist.[6]

The part just located at the south of the desert is a steppe, a semi-arid region, called the Sahel. It is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition in Africa between the Sahara desert to the north and the Sudanian Savanna to the south. The Sudanian Savanna is a broad belt of tropical savanna that runs east and west across the African continent, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Ethiopian Highlands in the east.

The Guinean region is a traditional name for the region that lies along the Gulf of Guinea. It stretches north through the forested tropical regions and ends at the Sahel. The Guinean Forests of West Africa is a belt of tropical moist broadleaf forests along the coast, running in the west from Sierra Leone and Guinea through Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana and Togo, ending at the Sanaga River of Cameroon in the east. The Upper Guinean forests and Lower Guinean forests are divided by the Dahomey Gap, a region of savanna and dry forest in Togo and Benin. The forests are a few hundred kilometres inland from the Atlantic Ocean coast on the southern part of West Africa.

Genetic background

Studies of human mitochondrial DNA suggest that all humans share common ancestors from Africa, originated in the southwestern regions near the coastal border of Namibia and Angola at the approximate coordinates 12.5° E, 17.5°S with a divergence in the migration path around 37.5°E, 22.5°N near the Red Sea.[7]

A particular haplogroup of DNA, haplogroup L2, evolved between 87,000 and 107,000 years ago[8] or approx. 90,000 YBP.[9] Its age and widespread distribution and diversity across the continent makes its exact origin point within Africa difficult to trace with any confidence,[10] however an origin for several L2 groups in West or Central Africa seems likely,[10] with the highest diversity in West Africa. Most of its subclades are largely confined to West and western-Central Africa.[11]

Africans bearing the E-V38 (E1b1a) likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west, approximately 19,000 years ago.[12] E-M2 (E1b1a1) likely originated in West Africa or Central Africa.[13]

Due to the large numbers of West Africans enslaved in the Atlantic slave trade, most African Americans are likely to have mixed ancestry from different regions of western Africa.[14] 60% of African-Americans (in the study) were of the E1b1a haplogroup, within which 22.9% were particularly of the E-M2 haplogroup; they also possessed numerous SNPs (e.g., U175, U209, U181, U290, U174, U186, and U247).[15]

Cultural history

Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary West African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states.[16] In contrast to most of Central, Southern and Southeast Africa, West Africa is not populated by Bantu-speaking peoples.[17]

Prehistory

Bingerville (13,000 BP) and Iwo-Eleru (11,000 BP) are the most early microlithic industries in West Africa.[18]

In the 10th millennium BCE, there was development in pyrotechnology and employment of subsistence strategy at Ounjougou, central Mali.[19] Prior to 9400 BCE, Niger-Congo speakers used matured ceramic technology (e.g., pots) in their economy to cook their grain (e.g., Digitaria exilis).[19] And archaeological evidence from central Mali shows that West African peoples had independently invented pottery in the region by that period (by at least 9400 BCE). It is believed that local peoples at that time had begun to become more settled, and to use pottery to store and cook indigenous grains (including pearl millet).[20]

During the Holocene, the Green Sahara underwent the process of becoming a desert and became the Sahara; this occurrence may have contributed to the start of domesticating field crops.[21] Akin to the Fertile Crescent of the Near East, the Niger River region of West Africa served as a cradle for field crop domestication and agriculture in Africa.[21] Yams, rice, sorghum, pearl millet, and cowpea are field crops that originate in Africa.[21] Taming of yams (e.g., D. praehensilis) likely began in the basin of the Niger River between eastern Ghana and western Nigeria (e.g., northern Benin).[21] Taming of rice (e.g., Oryza glaberrima) likely began in the Inner Niger Delta region of Mali.[21] Taming of pearl millet (e.g., Cenchrus americanus) likely began in the region of northern Mali and Mauritania.[21] Taming of cowpeas likely began in the region of northern Ghana.[21]

In West Africa, the wet phase ushered in expanding rainforest and wooded savannah from Senegal to Cameroon. Between 9000 and 5000 BCE, Niger–Congo speakers domesticated the oil palm and raffia palm. Two seed plants, black-eyed peas and voandzeia (African groundnuts) were domesticated, followed by okra and kola nuts. Since most of the plants grew in the forest, the Niger–Congo speakers invented polished stone axes for clearing forest.[22]

During the Green Sahara, at Gobero, there were two groups: the Kiffian and the Tenerian.[23] The Kiffian were hunters who lived approximately 8,000-10.000 years ago.[23] The Tenerian hunted, fished, and herded cattle approximately 4,500-7,000 years ago.[23]

In the steppes and savannah of the Sahara and Sahel, the Nilo-Saharan speakers started to collect and domesticate wild millet and sorghum between 8000 and 6000 BCE. Later, gourds, watermelons, castor beans, and cotton were also collected and domesticated. The people started capturing wild cattle and holding them in circular thorn hedges, resulting in domestication.[24]

Between 8000 BCE and 5000 BCE, Niger-Congo speakers independently developed agriculture (e.g., yams - Dioscorea).[25] Prior to 5000 BCE, their agricultural practices were spread throughout the woodland savanna, and afterward, were introduced southward into the West African rainforest belt.[25]

By 8000 BP, canoes (e.g., Dufuna canoe) were being utilized in West Africa.[26] While some Niger-Congo speakers may have utilized bows and arrows to hunt, other Niger-Congo speakers (e.g., Atlantic, Bak, Kru, Kwa, Ịjọ), who diverged from the hunters, may have utilized canoes to search for resources in river systems.[26]

Due to the complexity of pottery patterns and vastness of the area, where interactions between peoples occurred during the mid-Holocene, specifying which linguistic group (e.g., Niger-Congo, Nilo-Saharan, Afroasiatic) is the first settling population is challenging.[27] In any case, pottery in Gajiganna shares cultural similarity, across nearby areas of the southern Sahara, most of all, with northwestern Niger and northwestern Sudan.[27] Pottery from sites, dated to the second millennium BCE, close to the Mandara Mountains in Cameroon and Nigeria, also share affinity with the ceramics in Gajiganna.[27]

By 6300 BP, pottery began to appear in Konduga.[18] Occurring in the era of Mega Lake Chad, the pottery was decorated in the custom of Saharan ceramics.[28]

Before 5,500 BP, Kordofanian hunters may have traversed from West Africa, along what is now the Wadi Howar, into the Nuba Hills.[26]

The Korounkorokalé rockshelter was continually dwelled in by isolated Sub-Saharan Africans who kept a quartz microlithic tradition for a minimum of 5000 years and hunter-gatherer practices up until the mid to late first millennium CE (as asserted by MacDonald); the “little peoples” identified in the oral history of modern savanna residents when they first arrived in the area were used in reference to these Sub-Saharan Africans.[29]

In the Aïr Mountains, present-day Niger, copper was smelted independently of developments in the Nile Valley between 3000 and 2500 BC. The process used was not well developed, indicating that it was not brought from outside the region; it became more mature by about 1500 BC.[30]

In 4000 BP, there may have been a population that traversed from Africa (e.g., West Africa or West-Central Africa), through the Strait of Gibraltar, into the Iberian peninsula, where admixing between Africans and Iberians (e.g., of northern Portugal, of southern Spain) occurred.[31]

In the western Sahel, the rise of settled communities was largely the result of domestication of millet and sorghum. Archaeology points to sizeable urban populations in West Africa beginning in the 2nd millennium BCE. Symbiotic trade relations developed before the trans-Saharan trade, in response to the opportunities afforded by north-south diversity in ecosystems across deserts, grasslands, and forests. The agriculturists received salt from the desert nomads. The desert nomads acquired meat and other foods from pastoralists and farmers of the grasslands and from fishermen on the Niger River. The forest dwellers provided furs and meat.[32]

Dhar Tichitt and Oualata were prominent among the early urban centres, dated to 2000 BCE, in present-day Mauritania. About 500 stone settlements littered the region in the former savannah of the Sahara. Its inhabitants fished and grew millet. It has been found that the Soninke of the Mandé peoples were responsible for constructing such settlements. Around 300 BCE, the region became more desiccated and the settlements began to decline, most likely relocating to Koumbi Saleh. From the type of architecture and pottery, it is believed that Tichit was related to the subsequent Ghana Empire. Old Jenne (Djenne) began to be settled around 300 BCE, producing iron and with sizeable population, evidenced in crowded cemeteries. Living structures were made of sun-dried mud. By 250 BCE, Jenne was a large, thriving market town.[33][34]

Two migrations occurred, from first millennium BCE to first millennium CE, likely due to aridification, resulting in significant contributions being made to the overall protohistoric peopling of the Niger Bend.[35] One migration originated from the complex societies (e.g., Dhar Tichitt) of Mauritania and the other migration occurred with the iron metallurgists from Niger.[35] Peoples of the Niger Bend practiced “fishing, hunting, herding, agriculture, iron metallurgy, interregional (or even long-distance) commerce, and sometimes-hierarchical social organization.”[35]

Iron Age

The iron industry, in both smelting and forging for tools and weapons, appeared in Sub-Saharan Africa by about 2000-1200 BC.[36][37][38][39] Iron smelting facilities in Niger and Nigeria have been radiocarbon dated to 500 to 1000 BC,[40] and more recently in Nigeria from 2000 BC.[39] Though there is some uncertainty, some archaeologists believe that iron metallurgy was developed independently in sub-Saharan West Africa.[41][42] Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[39][42] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[42][43] Smelting furnaces appear in the Nok culture of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.[44][45][46][47] The increased use of iron and the spread of ironworking technology led to improved weaponry and enabled farmers to expand agricultural productivity and produce surplus crops, which together supported the growth of urban city-states into empires.

By 400 BC, contact had been made with the Mediterranean civilisations, including that of Carthage, and a regular trade in gold being conducted with the Sahara Berbers, as noted by Herodotus. The trade was fairly small until the camel was introduced, with Mediterranean goods being found in pits as far south as Northern Nigeria. A profitable trade had developed by which West Africans exported gold, cotton cloth, metal ornaments, and leather goods north across the trans-Saharan trade routes, in exchange for copper, horses, salt, textiles, and beads. Later, ivory, slaves, and kola nuts were also traded.

Djenné-Djenno

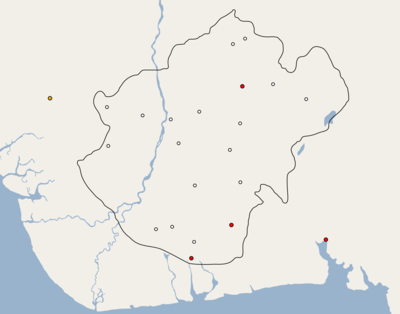

The civilization of Djenné-Djenno was located in the Niger River Valley in the country of Mali and is considered to be among the oldest urbanized centers and the best-known archaeology site in sub-Saharan Africa. This archaeological site is located about 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) away from the modern town and is believed to have been involved in long-distance trade and possibly the domestication of African rice. The site is believed to exceed 33 hectares (82 acres); however, this is yet to be confirmed with extensive survey work. With the help of archaeological excavations mainly by Susan and Roderick McIntosh, the site is known to have been occupied from 250 BCE to 900 CE The city is believed to have been abandoned and moved where the current city is located due to the spread of Islam and the building of the Great Mosque of Djenné. Previously, it was assumed that advanced trade networks and complex societies did not exist in the region until the arrival of traders from Southwest Asia. However, sites such as Djenné-Djenno disprove this, as these traditions in West Africa flourished long before.

Nok culture

In central Nigeria, around 1500 BCE, the Nok culture developed on the Jos Plateau, until it vanished under unknown circumstances by 200 or 300 CE. It was a highly centralised community.[1][48] The Nok people produced miniature, lifelike representations in terracotta, including human figures, human heads, elephants, and other animals. Iron use, in smelting and forging for tools, appears in Nok culture in Africa at least by 550 BC and possibly earlier, prior to 1000 BC.[49][50][51]

Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba kingdom of Ife and the Bini kingdom of Benin are now believed to be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[52]

Serer people

The prehistoric and ancient history of the Serer people of modern-day Senegambia has been extensively studied and documented over the years. Much of it comes from archaeological discoveries and Serer tradition rooted in the Serer religion.[53][54]

Material relics were found in different Serer countries, most of which refer to the past origins of Serer families, villages and Serer Kingdoms, some of these Serer relics included gold, silver and metals.[53][55]

The known objects found in Serer countries are divided into two types, the remnants of earlier populations, and the laterite megaliths carved planted in circular structures with stones directed towards the east are found only in small parts of the ancient Serer kingdom of Saloum.

Senegambian stone circles

The Senegambian stone circles are megaliths found in Gambia north of Janjanbureh and in central Senegal. The megaliths found in Senegal and Gambia are sometimes divided into four large sites: Sine Ngayene and Wanar in Senegal, and Wassu and Kerbatch in the Central River Region in Gambia. Researchers are not certain when these monuments were built, but the generally accepted range is between the third century BCE and the sixteenth century CE. Archaeologists have also found pottery sherds, human burials, and some grave goods and metals.[56] The monuments consist of what were originally upright blocks or pillars (some have collapsed), made of mostly laterite with smooth surfaces.

The construction of the stone monuments shows evidence of a prosperous and organised society based on the amount of labour required to build such structures. The builders of these megaliths are unknown, but some believe that the Serer people are the builders. This hypothesis comes from the fact that the Serer still use funerary houses like those found at Wanar.[57]

Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of kingdoms or empires that were centred on the sahel, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara. The wealth of the states came from controlling the trade routes across the desert. Their power came from having large pack animals like camels and horses that were fast enough to keep a large empire under central control and were also useful in battle. All of these empires were also quite decentralised with member cities having a great deal of autonomy.

Ghana

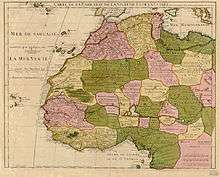

The Ghana Empire may have been an established kingdom as early as the 7th century CE, founded among the Soninke, a Mandé people who lived at the crossroads of this new trade, around the city of Kumbi Saleh. Ghana was first mentioned by Arab geographer Al-Farazi in the late 8th century. After 800, the empire expanded rapidly, coming to dominate the entire western Sudan; at its height, the empire could field an army of 200,000 soldiers.

Ghana was inhabited by urban dwellers and rural farmers. The urban dwellers were the administrators of the empire, who were Muslims, and the Ghana (king), who practised traditional religion. Two towns existed, one where the Muslim administrators and Berber-Arabs lived, which was connected by a stone-paved road to the king's residence. The rural dwellers lived in villages, which joined together into broader polities that pledged loyalty to the Ghana. The Ghana was viewed as divine, and his physical well-being reflected on the whole society. Ghana converted to Islam around 1050, after conquering Aoudaghost.[58]

The Ghana Empire grew wealthy by taxing the trans-Saharan trade that linked Tiaret and Sijilmasa to Aoudaghost. Ghana controlled access to the goldfields of Bambouk, southeast of Koumbi Saleh. A percentage of salt and gold going through its territory was taken. The empire was not involved in production.[59]

In the 10th century, however, Islam was steadily growing in the region, and due to various influences, including internal dynastic struggles coupled with competing foreign interests (namely Almoravid intervention). By the 11th century, Ghana was in decline. It was once thought that the sacking of Koumbi Saleh by Berbers under the Almoravid dynasty in 1076 was the cause. This is no longer accepted. Several alternative explanations are cited. One important reason is the transfer of the gold trade east to the Niger River and the Taghaza Trail, and Ghana's consequent economic decline. Another reason cited is political instability through rivalry among the different hereditary polities.[60] The empire came to an end in 1230, when Takrur in northern Senegal took over the capital.[61][62]

Sosso

The first successor to the Ghana Empire was that of the Sosso, a Takrur people who built their empire on the ruins of the old. Despite initial successes, however, the Sosso king Soumaoro Kanté was defeated by the Mandinka prince Sundiata Keita at the Battle of Kirina in 1240, toppling the Sosso and guaranteeing the supremacy of Sundiata's new Mali Empire.

Mali

The Mali Empire began in the 13th century CE, eventually creating a centralised state including most of West Africa. It originated when a Mande (Mandingo) leader, Sundiata (Lord Lion) of the Keita clan, defeated Soumaoro Kanté, king of the Sosso or southern Soninke, at the Battle of Kirina in c. 1235. Sundiata continued his conquest from the fertile forests and Niger Valley, east to the Niger Bend, north into the Sahara, and west to the Atlantic Ocean, absorbing the remains of the Ghana Empire. Sundiata took on the title of mansa. He established the capital of his empire at Niani.[63]

Although the salt and gold trade continued to be important to the Mali Empire, agriculture and pastoralism was also critical. The growing of sorghum, millet, and rice was a vital function. On the northern borders of the Sahel, grazing cattle, sheep, goats, and camels were major activities. Mande society was organised around the village and land. A cluster of villages was called a kafu, ruled by a farma. The farma paid tribute to the mansa. A dedicated army of elite cavalry and infantry maintained order, commanded by the royal court. A formidable force could be raised from tributary regions, if necessary.[64]

Conversion to Islam was a gradual process. The power of the mansa depended on upholding traditional beliefs and a spiritual foundation of power. Sundiata initially kept Islam at bay. Later mansas were devout Muslims but still acknowledged traditional deities and took part in traditional rituals and festivals, which were important to the Mande. Islam became a court religion under Sundiata's son Uli I (1225–1270). Mansa Uli made a pilgrimage to Mecca, becoming recognised within the Muslim world. The court was staffed with literate Muslims as secretaries and accountants. Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta left vivid descriptions of the empire.[64]

Mali reached the peak of its power and extent in the 14th century, when Mansa Musa (1312–1337) made his famous hajj to Mecca with 500 slaves, each holding a bar of gold worth 500 mithqal.[65] Mansa Musa's hajj devalued gold in Mamluk Egypt for a decade. He made a great impression on the minds of the Muslim and European world. He invited scholars and architects like Ishal al-Tuedjin (al-Sahili) to further integrate Mali into the Islamic world.[64]

The Mali Empire saw an expansion of learning and literacy. In 1285, Sakura, a freed slave, usurped the throne. This mansa drove the Tuareg out of Timbuktu and established it as a center of learning and commerce. The book trade increased, and book copying became a very respectable and profitable profession. Kankou Musa I founded a university at Timbuktu and instituted a programme of free health care and education for Malian citizens with the help of doctors and scholars brought back from his legendary hajj. Timbuktu and Djenné became important centres of learning within the Muslim world.[66]

After the reign of Mansa Suleyman (1341–1360), Mali began its spiral downward. Mossi cavalry raided the exposed southern border. Tuareg harassed the northern border to retake Timbuktu. Fulani (Fulbe) eroded Mali's authority in the west by establishing the independent Imamate of Futa Toro, a successor to the kingdom of Takrur. Serer and Wolof alliances were broken. In 1545 to 1546, the Songhai Empire took Niani. After 1599, the empire lost the Bambouk goldfields and disintegrated into petty polities.[64]

Kankou Musa's successors, however, weakened the empire significantly, leading the city-state of Gao to make a bid for independence and regional power in the 15th century. Under the leadership of Sonni Ali (r. 1464–1492), the Songhai of Gao formed the Songhai Empire, which would fill the vacuum left by the Mali Empire's collapse.

Songhai

The Songhai people are descended from fishermen on the Middle Niger River. They established their capital at Kukiya in the 9th century CE and at Gao in the 12th century. The Songhai speak a Nilo-Saharan language.[67]

Sonni Ali, a Songhai, began his conquest by capturing Timbuktu in 1468 from the Tuareg. He extended the empire to the north, deep into the desert, pushed the Mossi further south of the Niger, and expanded southwest to Djenne. His army consisted of cavalry and a fleet of canoes. Sonni Ali was not a Muslim, and he was portrayed negatively by Berber-Arab scholars, especially for attacking Muslim Timbuktu. After his death in 1492, his heirs were deposed by General Muhammad Ture, a Muslim of Soninke origins.[68]

Muhammad Ture (1493–1528) founded the Askiya Dynasty, askiya being the title of the king. He consolidated the conquests of Sonni Ali. Islam was used to extend his authority by declaring jihad on the Mossi, reviving the trans-Saharan trade, and having the Abbasid "shadow" caliph in Cairo declare him as caliph of Sudan. He established Timbuktu as a great center of Islamic learning. Muhammad Ture expanded the empire by pushing the Tuareg north, capturing Aïr in the east, and capturing salt-producing Taghaza. He brought the Hausa states into the Songhay trading network. He further centralised the administration of the empire by selecting administrators from loyal servants and families and assigning them to conquered territories. They were responsible for raising local militias. Centralisation made Songhay very stable, even during dynastic disputes. Leo Africanus left vivid descriptions of the empire under Askiya Muhammad. Askiya Muhammad was deposed by his son in 1528. After much rivalry, Muhammad Ture's last son Askiya Daoud (1529–1582) assumed the throne.[69]

In 1591, Morocco invaded the Songhai Empire under Ahmad al-Mansur of the Saadi Dynasty to secure the goldfields of the Sahel. At the Battle of Tondibi, the Songhai army was defeated. The Moroccans captured Djenne, Gao, and Timbuktu, but they were unable to secure the whole region. Askiya Nuhu and the Songhay army regrouped at Dendi in the heart of Songhai territory where a spirited guerrilla resistance sapped the resources of the Moroccans, who were dependent upon constant resupply from Morocco. Songhai split into several states during the 17th century.

Morocco found its venture unprofitable. The gold trade had been diverted to Europeans on the coast. Most of the trans-Saharan trade was now diverted east to Bornu. Expensive equipment purchased with gold had to be sent across the Sahara, an unsustainable scenario. The Moroccans who remained married into the population and were referred to as Arma or Ruma. They established themselves at Timbuktu as a military caste with various fiefs, independent from Morocco. Amid the chaos, other groups began to assert themselves, including the Fulani of Futa Tooro who encroached from the west. The Bambara Empire, one of the states that broke from Songhai, sacked Gao. In 1737, the Tuareg massacred the Arma.[70][71]

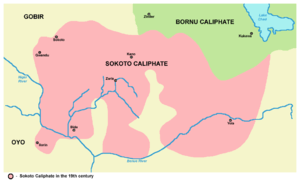

Sokoto Caliphate

The Fulani were migratory people. They moved from Mauritania and settled in Futa Tooro, Futa Djallon, and subsequently throughout the rest of West Africa. By the 14th century CE, they had converted to Islam. During the 16th century, they established themselves at Macina in southern Mali. During the 1670s, they declared jihads on non-Muslims. Several states were formed from these jihadist wars, including Bundu, the Imamate of Futa Toro, the Imamate of Futa Jallon, and the Massina Empire. The most important of these states was the Sokoto Caliphate or Fulani Empire.

In the city of Gobir, Usman dan Fodio (1754–1817) accused the Hausa leadership of practising an impure version of Islam and of being morally corrupt. In 1804, he launched the Fulani War as a jihad among a population that was restless about high taxes and discontented with its leaders. Jihad fever swept northern Nigeria, with strong support among both the Fulani and the Hausa. Usman created an empire that included parts of northern Nigeria, Benin, and Cameroon, with Sokoto as its capital. He retired to teach and write and handed the empire to his son Muhammed Bello. The Sokoto Caliphate lasted until 1903 when the British conquered northern Nigeria.[72]

Forest empires and states

Akan Kingdoms and emergence of Asante Empire

The Akan speak a Kwa Language. The speakers of Kwa languages are believed to have come from East/Central Africa, before settling in the Sahel.[73] By the 12th century, the Akan Kingdom of Bonoman (Bono State) was established. Bonoman was a trading state created by the Abron people. Bonoman was a medieval Akan kingdom in what is now the Brong-Ahafo Region of Ghana and eastern Ivory Coast. It is generally accepted as the origin of the subgroups of the Akan people who migrated out of the state at various times to create new Akan states in search of gold. The gold trade, which started to boom in Bonoman as early in the 12th century, was the genesis of Akan power and wealth in the region, beginning in the Middle Ages.[74] During the 13th century, when the gold mines in modern-day Mali started to become depleted, Bonoman and later other Akan states began to rise to prominence as the major players in the gold trade.

It was Bonoman and other Akan kingdoms like Denkyira, Akyem, Akwamu which were the predecessors to what became the all-powerful Empire of Ashanti. When and how the Ashante got to their present location is debatable. What is known is that by the 17th century an Akan people were identified as living in a state called Kwaaman. The location of the state was north of Lake Bosomtwe. The state's revenue was mainly derived from trading in gold and kola nuts and clearing forest to plant yams. They built towns between the Pra and Ofin rivers. They formed alliances for defence and paid tribute to Denkyira one of the more powerful Akan states at that time along with Adansi and Akwamu. During the 16th century, Ashante society experienced sudden changes, including population growth because of cultivation of New World plants such as cassava and maize and an increase in the gold trade between the coast and the north.[75]

By the 17th century, Osei Kofi Tutu I (c. 1695–1717), with help of Okomfo Anokye, unified what became the Ashante into a confederation with the Golden Stool as a symbol of their unity and spirit. Osei Tutu engaged in a massive territorial expansion. He built up the Ashante army based on the Akan state of Akwamu, introducing new organisation and turning a disciplined militia into an effective fighting machine. In 1701, the Ashante conquered Denkyira, giving them access to the coastal trade with Europeans, especially the Dutch. Opoku Ware I (1720–1745) engaged in further expansion, adding other southern Akan states to the growing empire. He turned north adding Techiman, Banda, Gyaaman, and Gonja, states on the Black Volta. Between 1744 and 1745, Asantehene Opoku attacked the powerful northern state of Dagomba, gaining control of the important middle Niger trade routes. Kusi Obodom (1750–1764) succeeded Opoku. He solidified all the newly won territories. Osei Kwadwo (1777–1803) imposed administrative reforms that allowed the empire to be governed effectively and to continue its military expansion. Osei Kwame Panyin (1777–1803), Osei Tutu Kwame (1804–1807), and Osei Bonsu (1807–1824) continued territorial consolidation and expansion. At its height, the Ashante Empire included most of present-day Ghana and large parts of Côte d'Ivoire.[76]

The ashantehene inherited his position from his mother. He was assisted at the capital, Kumasi, by a civil service of men talented in trade, diplomacy, and the military, with a head called the Gyaasehene. Men from Arabia, Sudan, and Europe were employed in the civil service, all of them appointed by the ashantehene. At the capital and in other towns, the ankobia or special police were used as bodyguards to the ashantehene, as sources of intelligence, and to suppress rebellion. Communication throughout the empire was maintained via a network of well-kept roads from the coast to the middle Niger and linking together other trade cities.[77][78]

For most of the 19th century, the Ashante Empire remained powerful. It was later destroyed in 1900 by British superior weaponry and organisation following the four Anglo-Ashanti wars.[79]

Dahomey

The Dahomey Kingdom was founded in the early 17th century CE when the Aja people of the Allada kingdom moved northward and settled among the Fon. They began to assert their power a few years later. In so doing they established the Kingdom of Dahomey, with its capital at Agbome. King Houegbadja (c. 1645–1685) organised Dahomey into a powerful centralised state. He declared all lands to be owned of the king and subject to taxation. Primogeniture in the kingship was established, neutralising all input from village chiefs. A "cult of kingship" was established. A captive slave would be sacrificed annually to honour the royal ancestors. During the 1720s, the slave-trading states of Whydah and Allada were taken, giving Dahomey direct access to the slave coast and trade with Europeans. King Agadja (1708–1740) attempted to end the slave trade by keeping the slaves on plantations producing palm oil, but the European profits on slaves and Dahomey's dependency on firearms were too great. In 1730, under king Agaja, Dahomey was conquered by the Oyo Empire, and Dahomey had to pay tribute. Taxes on slaves were mostly paid in cowrie shells. During the 19th century, palm oil was the main trading commodity.[80] France conquered Dahomey during the Second Franco-Dahomean War (1892–1894) and established a colonial government there. Most of the troops who fought against Dahomey were native Africans.

Yoruba

Traditionally, the Yoruba people viewed themselves as the inhabitants of a united empire, in contrast to the situation today, in which "Yoruba" is the cultural-linguistic designation for speakers of a language in the Niger–Congo family. The name comes from a Hausa word to refer to the Oyo Empire. The first Yoruba state was Ile-Ife, said to have been founded around 1000 CE by a supernatural figure, the first oni Oduduwa. Oduduwa's sons would be the founders of the different city-states of the Yoruba, and his daughters would become the mothers of the various Yoruba obas, or kings. Yoruba city-states were usually governed by an oba and an iwarefa, a council of chiefs who advised the oba. By the 18th century, the Yoruba city-states formed a loose confederation, with the Oni of Ife as the head and Ife as the capital. As time went on, the individual city-states became more powerful with their obas assuming more powerful spiritual positions and diluting the authority of the Oni of Ife. Rivalry became intense among the city-states.[81]

The Oyo Empire rose in the 16th century. The Oyo state had been conquered in 1550 by the kingdom of Nupe, which was in possession of cavalry, an important tactical advantage. The alafin (king) of Oyo was sent into exile. After returning, Alafin Orompoto (c. 1560–1580) built up an army based on heavily armed cavalry and long-service troops. This made them invincible in combat on the northern grasslands and in the thinly wooded forests. By the end of the 16th century, Oyo had added the western region of the Niger to the hills of Togo, the Yoruba of Ketu, Dahomey, and the Fon nation.

A governing council served the empire, with clear executive divisions. Each acquired region was assigned a local administrator. Families served in king-making capacities. Oyo, as a northern Yoruba kingdom, served as middle-man in the north-south trade and connecting the eastern forest of Guinea with the western and central Sudan, the Sahara, and North Africa. The Yoruba manufactured cloth, ironware, and pottery, which were exchanged for salt, leather, and most importantly horses from the Sudan to maintain the cavalry. Oyo remained strong for two hundred years.[61][82] It became a protectorate of Great Britain in 1888, before further fragmenting into warring factions. The Oyo state ceased to exist as any sort of power in 1896.[83]

Benin

The Kwa Niger–Congo speaking Edo people. By the mid-15th century, the Benin Empire was engaged in political expansion and consolidation. Under Oba (king) Ewuare (c. 1450–1480 CE), the state was organised for conquest. He solidified central authority and initiated 30 years of war with his neighbours. At his death, the Benin Empire extended to Dahomey in the west, to the Niger Delta in the east, along the west African coast, and to the Yoruba towns in the north.

Ewuare's grandson Oba Esigie (1504–1550) eroded the power of the uzama (state council) and increased contact and trade with Europeans, especially with the Portuguese who provided a new source of copper for court art. The oba ruled with the advice from the uzama, a council consisting of chiefs of powerful families and town chiefs of different guilds. Later its authority was diminished by the establishment of administrative dignitaries. Women wielded power. The queen mother who produced the future oba wielded immense influence.[84]

Benin was never a significant exporter of slaves, as Alan Ryder's book Benin and the Europeans showed. By the early 1700s, it was wrecked with dynastic disputes and civil wars. However, it regained much of its former power in the reigns of Oba Eresoyen and Oba Akengbuda. After the 16th century, Benin mainly exported pepper, ivory, gum, and cotton cloth to the Portuguese and Dutch who resold it to other African societies on the coast. In 1897, the British sacked the city.[85]

Niger Delta and Igbo

The Niger Delta comprised numerous city-states with numerous forms of government. These city-states were protected by the waterways and thick vegetation of the delta. The region was transformed by trade in the 17th century CE. The delta's city-states were comparable to those of the Swahili people in East Africa. Some, like Bonny, Kalabari, and Warri, had kings. Others, like Brass, were republics with small senates, and those at Cross River and Old Calabar were ruled by merchants of the ekpe society. The ekpe society regulated trade and made rules for members known as house systems. Some of these houses, like the Pepples of Bonny, were well known in the Americas and Europe.[88]

The Igbo primarily lived east of the delta (but with the Anioma on the west of the Niger River). The Kingdom of Nri rose in the 10th century CE, with the Eze Nri being its leader. It was a political entity composed of villages, and each village was autonomous and independent with its own territory and name, each recognised by its neighbours. Villages were democratic with all males and sometimes females a part of the decision-making process. Graves at Igbo-Ukwu (800 CE) contained brass artefacts of local manufacture and glass beads from Egypt or India, indicative of extraregional trade.[89][90]

The Aro Confederacy was a political union orchestrated by the Igbo subgroup, the Aro people, centered in the Arochukwu Kingdom in present-day south-eastern Nigeria. It was founded at the end of the 16th century, and their influence and presence was across Eastern Nigeria into parts of the Niger Delta and Southern Igala during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Slave trade

Following the collapse of the Songhai Empire, a number of smaller states arose across West Africa, including the Bambara Empire of Ségou, the lesser Bambara kingdom of Kaarta, the Fula/Malinké kingdom of Khasso (in present-day Mali's Kayes Region), and the Kénédougou Empire of Sikasso.

European traders first became a force in the region in the 15th century, with the 1445 establishment of a Portuguese trading post at Arguin Island, off the coast of present-day Senegal; by 1475, Portuguese traders had reached as far as the Bight of Benin. The transatlantic African slave trade began almost immediately after based on the already well established slave trading capacity serving the Islamic world, with the Portuguese taking hundreds of captives back to their country for use as slaves; however, it would not begin on a grand scale until Christopher Columbus's voyage to the Americas and the subsequent demand for cheap colonial labour. In 1510, the Spanish crown legalised the African slave trade, followed by the English in 1562. By 1650 the slave trade was in full force at a number of sites along the coast of West Africa, and over the coming centuries would result in severely reduced growth for the region's population and economy. The expanding Atlantic slave trade produced significant populations of West Africans living in the New World, recently colonised by Europeans. The oldest known remains of African slaves in the Americas were found in Mexico in early 2006; they are thought to date from the late 16th century and the mid-17th century.[91]

As the demand for slaves increased, some African rulers sought to supply the demand by constant war against their neighbours, resulting in fresh captives. States such as Dahomey (in modern-day Benin) and the Bambara Empire-based much of their economy on the exchange of slaves for European goods, particularly firearms that they then employed to capture more slaves. Moreover, during colonial rule both British and Dutch authorities were active in recruiting African slaves into the national military service. As it was believed that African black population was more immune than Europeans to the tropical diseases present in India and Indonesia. Recruitment changed format after the Atlantic slave trade was abolished by European and American governments in 19th century. For instance, 1831 was the first year when only volunteers were accepted for the military service.[92] Though slavery in the Americas persisted in some capacity even after it was prohibited; the last country to abolish the institution was Brazil in 1888. Descendants of West Africans make up large and important segments of the population in Brazil, the Caribbean, the United States, and throughout the New World.

African Americans in several major US cities who took part in a genetic research study, concluded that their common ancestry originated most prominently in western Africa which is consistent with prior genetic studies and the history of slave trade.[93]

Colonial period

In 1725, the cattle-herding Fulanis of Fouta Djallon launched the first major reformist jihad of the region, overthrowing the local animist, Mande-speaking elites and attempting to somewhat democratise their society. A similar movement occurred on a much broader scale in the Hausa city-states of Nigeria under Uthman dan Fodio; an imam influenced by the teachings of Sidi Ahmed al-Tidjani, Uthman preached against the elitist Islam of the then-dominant Qadiriyyah brotherhood, winning a broad base of support amongst the common people. Uthman's Fulani Empire was soon one of the region's largest states, and inspired the later jihads of Massina Empire founder Seku Amadu in present-day Mali, and the cross-Sudan Toucouleur conqueror El Hadj Umar Tall.

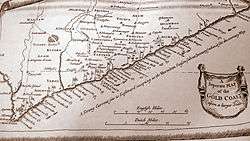

At the same time, the Europeans started to travel into the interior of Africa to trade and explore. Mungo Park (1771–1806) made the first serious expedition into the region's interior, tracing the Niger River as far as Timbuktu. French armies followed not long after. In 1774 it was noted that the extensive coastline and deep rivers of Africa had not been utilised for 'correspondence or commerce', yet maps in this ancient volume clearly show the "Gum Coast", "Grain Coast", "Ivory Coast", and "Gold Coast".[94] Malachy Postlethwayt writes "It is melancholy to observe that a country, which has near ten thousand miles sea-coast, and noble, large, deep rivers, should yet have no navigation; streams penetrating into the very center of the country, but of no benefit to it, innumerable people, without knowledge of each other, correspondence, or commerce."[94]

Scramble for Africa

In the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s the Europeans started to colonise the inland of West Africa, they had previously mostly controlled trading ports along the coasts and rivers. Samory Ture's newly founded Wassoulou Empire was the last to fall, and with his capture in 1898, military resistance to French colonial rule effectively ended.

France dominated West Africa, followed by Britain; small colonial operations were held by Germany (until 1914), and also Spain and Portugal. Only Liberia was independent before 1958. After the slave trade died out, Denmark and the Netherlands sold off their small holdings. Britain operated from four small coastal areas left over from slavery days, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, Lagos and the Niger. The trade in useful tropical products reached £4 million-a-year, and was entirely handled by a small number of resident merchants. There were no permanent British settlers or military bases. The posts were held entirely for trade purposes, and also as calling stations. London had no long-term plans to join them together or go inland. British diplomats negotiated military agreements with local tribes, who needed British protection from the expansionist Ashanti tribes. Britain fought repeated Anglo-Ashante wars in Gold Coast in 1823, 1824-1831, 1863–64, 1873–74, 1895–96 and 1900. Only the last two were clear British victories.[95] French pretensions in West Africa were much more ambitious, and involved not just trade, but rebuilding the lost Empire, And bringing new populations in the umbrella of French civilization and Catholicism. There were dreams of consolidating a vast African empire by moving down from the Mediterranean into the Sahara desert, moving east toward the Nile River, and moving south Toward King Leopold’s Congo.[96]

Post-colonial West Africa

Following World War II, campaigns for independence sprung up across West Africa, most notably in Ghana under the Pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972). After a decade of protests, riots and clashes, French West Africa voted for autonomy in a 1958 referendum, dividing into the states of today; most of the British colonies gained autonomy the following decade. Ghana became the first country of sub-Saharan Africa to achieve independence in 1957, followed by Guinea under the guidance Sekou Touré the next year.[97] Out of the 17 nations that achieved their independence in 1960, the Year of Africa, nine were West African countries.[97] Many founding fathers of West African nations, like Nkrumah, Touré, Senghor, Modibo Keïta, Sylvanus Olympio, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Siaka Stevens and Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, consolidated their power during the post-independence 1960s by gradually eroding democratic institutions and civil society.[98] In 1973, Guinea-Bissau proclaimed its independence from Portugal, and was internationally recognised following the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal.

West African political history has been characterised by African socialism. Senghor, Nkrumah and Touré all embraced the idea of African socialism, whereas Houphouët-Boigny and Liberia's William Tubman remained suspicious of it.[99] 1983 saw the rise of socialist Thomas Sankara, often titled the "Che Guevara of Africa", to power in Burkina Faso.[100]

Since independence, West Africa has suffered from the same problems as much of the African continent, particularly dictatorships, political corruption and military coups. At the time of his death in 2005, for example, Togo's Étienne Eyadéma was among the world's longest-ruling dictators. Inter-country conflicts have been few, with Mali and Burkina Faso's nearly bloodless Agacher Strip War being a rare exception.

Post-Colonial civil wars

The region of West Africa has seen a number of civil wars in its recent past including the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970), two civil wars in Liberia in 1989 and 1999, a decade of fighting in Sierra Leone from 1991–2002, the Guinea-Bissau Civil War from 1998–1999 and a recent conflict in Côte d'Ivoire that began on 2002 ending 2007 and a second conflict in 2010–11.

Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970)

After gaining full independence from the British Empire in 1963, Nigeria established the first republic. The republic was heavily influenced by British democracy and relied on majority rule.[101] The first republic fell after a successful coup d'état led by southern Nigerian rebels on 15 January 1966.

The fall of the first republic left behind apparent political division between North and South Nigeria. This led to the military governor of south-eastern Nigeria, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, deeming that because of northern massacres and electoral fraud, the Southeast of Nigeria should be an independent state. The independent state became known as the Republic of Biafra.[102]

Northern Nigeria opposed the claim of southern secession. The Nigerian government called for police action in the area. The armed forces of Nigeria were sent in to occupy and take back the Republic of Biafra. Nigerian forces seized Biafra in a series of phases. The phases were, the Capture of Nsukka, the Capture of Ogoja, Capture of Abakaliki, and the Capture of Enugu. All of the perpetrated phases and campaigns were successful due to the advantaged army of Nigeria.[103] By 1970, Biafraian general, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu, fled to the neighboring nation of Côte d'Ivoire. After the flee, Biafra, facing no other option, surrendered due to lack of resources and leadership. Biafra quickly united with the northern Nigeria on 15 January 1970.[104] The conflict is estimated to have killed roughly 1 million people.[105]

First Liberian Civil War (1989–1997)

The First Liberian Civil War was an internal conflict in Liberia from 1989 until 1997. The conflict killed about 250,000 people[106] and eventually led to the involvement of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and of the United Nations. The peace did not last long, and in 1999 the Second Liberian Civil War broke out.

Samuel Doe had led a rebellion that overthrew the elected government in 1980, and in 1985 held elections that were widely considered fraudulent. There had been one unsuccessful coup by a former military leader. In December 1989, former government minister Charles Taylor moved into the country from neighboring Ivory Coast to start an uprising meant to topple the Doe government.

Taylor's forces, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) battled with Prince Johnson's rebel group, the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL) – a faction of NPFL – for control in Monrovia. In 1990, Johnson seized the capital of Monrovia and executed Doe brutally.

Second Liberian Civil War (1999–2003)

The Second Liberian Civil War began in 1999 when a rebel group backed by the government of neighbouring Guinea, the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD), emerged in northern Liberia. In early 2003, a second rebel group, the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), emerged in the south, and by June–July 2003, Charles Taylor's government controlled only a third of the country.

The capital Monrovia was besieged by LURD, and the group's shelling of the city resulted in the deaths of many civilians. Thousands of people were displaced from their homes as the result of the conflict.

The Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed by the warring parties on August 18, 2003 marking the political end of the conflict and beginning of the country's transition to democracy under the National Transitional Government of Liberia which was led by interim President Gyude Bryant until the Liberian general election of 2005.

Sierra Leone Civil War (1991–2002)

The civil war began on 23 March 1991 as a result of an attempted overthrow against the administration of president, Joseph Saidu Momoh. The rebels went under the guise of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) led by Foday Sankoh a previous army corporal.[107] The Sierra Leoneian government called for action and soon the Sierra Leone Army (SLA) was sent in to control the situation and take back RUF occupied territory.

By 1992 president Joseph Momoh was ousted by a successful military coup led by Captain Valentine Strasser. Capitan Strasser, soon established multi-party democratic elections in the region.

On 18 January 2002, the civil war was officially ended by former president Kabbah. During the 11 year conflict, roughly 50,000 Sierra Leoneians were killed with 2,000,000 displaced.[108]

Guinea-Bissau Civil War (1998–1999)

Before the civil war began, an attempted coup d'état took place led by military Brigadier General Ansumane Mané. Mané leading the coup, blamed the presidency of Joao Bernardo Vieira for the poverty and corruption of Guinea Bissau. President Vieira, controlling the armed forces, soon fired Mané from his position of Brigadier General.[109] He was fired on charges of supplying Senegal rebels.[110]

On 7 June 1998, a second coup d'état began. The coup once again failed. Soon after, rebels received aid from the neighboring nations of Senegal and Guinea-Conakry.

The conflict sparked a civil war. Many soldiers in the armed forces of Guinea-Bissau joined the side of the rebels. This was in part, due to the soldiers not being paid by the government. The rebels continued to fight from 1998 to 1999. President Vieira was ousted on 7 May 1999. By 10 May 1999, the war ended when President Vieira signed an unconditional surrender in a Portuguese embassy.[111]

Approximately 655 were killed as a result of the conflict.[112]

First Ivorian Civil War (2002-2007)

In the early 2000s, the Ivory Coast (also known as Côte d'Ivoire) experienced an economic rescission. The rescission began as a result of the previous economic boom crashing the economy as a whole. This led to the predominantly Muslim north and predominantly Christian south of the Ivory Coast becoming politically divided.[113]

The southern Ivory Coast was in control of the Ivorian government. The north however, was under the power of the rebel movement. The civil war between the two began officially on 19 September 2002 when rebels launched a series of attacks on the south. The city of Abidjan was primarily targeted. Northern rebels were successful in the attacks. As a result of the chaos, president Robert Guéï was killed in the rebellions.[114]

The south retailed with military action. France supported the south and sent 2500 soldiers to the region and called for United Nations action. French action in the area went under the guise and codename of Operation Unicorn.

By 2004 most fighting in the region ceased. On 4 March 2007 the civil war official ended with the signing of a peace treaty.

Second Ivorian Civil War (2010-2011)

Health

Medicine

Traditional African medicine is a holistic discipline involving indigenous herbalism and African spirituality. Practitioners claim to be able to cure various and diverse conditions.[115] Modern science has, in the past, considered methods of traditional knowledge as primitive and backward.[116] Under colonial rule, traditional diviner-healers were outlawed because they were considered by many nations to be practitioners of witchcraft and declared illegal by the colonial authorities, creating a war against witchcraft and magic. During this time, attempts were also made to control the sale of herbal medicines.[115] As colonialism and Christianity spread through Africa, colonialists built general hospitals and Christian missionaries built private ones, with the hopes of making headway against widespread diseases. Little was done to investigate the legitimacy of these practices, as many foreigners believed that the native medical practices were pagan and superstitious and could only be suitably fixed by inheriting Western methods.[117] During times of conflict, opposition has been particularly vehement as people are more likely to call on the supernatural realm.[115] Consequently, doctors and health practitioners have, in most cases, continued to shun traditional practitioners despite their contribution to meeting the basic health needs of the population.[116] In recent years, the treatments and remedies used in traditional African medicine have gained more appreciation from researchers in Western science. Developing countries have begun to realise the high costs of modern health care systems and the technologies that are required, thus proving Africa's dependence to it.[116] Due to this, interest has recently been expressed in integrating traditional African medicine into the continent's national health care systems.[115]

Disease

Disease has been a hindrance to human development in West Africa throughout history. The environment, especially the tropical rain-forests, allow many single cell organisms, parasites, and bacteria to thrive and prosper. Prior to the slave trade, West Africans strived to maintain ecological balance, controlling vegetation and game, and thereby minimising the prevalence of local diseases. The increased amount and intensity of warfare due to the slave trade meant that the ecological balance could not be sustained. Endemic diseases became epidemic in scale. Genetic mutations developed that provided increased resistance to disease, such as sickle cell, evident in the Kwa forest agriculturalists from c. 700 CE, providing some protection from malaria.[118]

HIV/AIDS

In the 1990s, AIDS became a significant problem for the region, particularly in Côte d'Ivoire, Liberia, and Nigeria.[119] The onset of the HIV epidemic in the region began in 1985 with reported cases in Benin[120] and Nigeri,[121] and in nearby countries, such as Côte d'Ivoire, in subsequent years.[122]

AIDS was at first considered a disease of gay men and drug addicts, but in Africa it took off among the general population. As a result, those involved in the fight against HIV began to emphasize aspects such as preventing transmission from mother to child, or the relationship between HIV and poverty, inequality of the sexes, and so on, rather than emphasizing the need to prevent transmission by unsafe sexual practices or drug injection. This change in emphasis resulted in more funding, but was not effective in preventing a drastic rise in HIV prevalence.[123] The global response to HIV and AIDS has improved considerably in recent years. Funding comes from many sources, the largest of which are the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.[124]

As of 2011, HIV prevalence in western Africa is lowest in Senegal and highest in Nigeria, which has the second largest number of people living with HIV in Africa after South Africa. Nigeria's infection rate relative to the entire population, however, is much lower (3.7 percent) compared to South Africa's (17.3 percent).[125]

Ebola virus disease

Ebola virus disease, first identified in 1976, typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, including West Africa.[126] From 1976 through 2013, the World Health Organization reported 1,716 confirmed cases.[126][127] The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak, which is affecting Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Nigeria[128][129] The outbreak began in Guinea in December 2013, but was not detected until March 2014,[130] after which it spread to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria. The outbreak is caused by the Zaire ebolavirus, known simply as the Ebola virus (EBOV). It is the most severe outbreak of Ebola in terms of the number of human cases and fatalities since the discovery of the virus in 1976.[131]

As of 16 August 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a total of 2,240 suspected cases and 1,229 deaths (1,383 cases and 760 deaths being laboratory confirmed).[132] On 8 August, it formally designated the outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern.[133] This is a legal designation used only twice before (for the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic and the 2014 resurgence of polio) and invokes legal measures on disease prevention, surveillance, control, and response, by 194 signatory countries.[134] Various aid organisations and international bodies, including the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the European Commission have donated funds and mobilised personnel to help counter the outbreak; charities including Médecins Sans Frontières, the Red Cross,[135] and Samaritan's Purse are also working in the area.

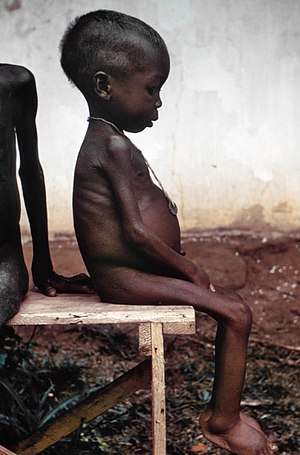

Famine

Famine has been an occasional but serious problem in West Africa. In 1680s, famine extended across the entire Sahel, and in 1738 half the population of Timbuktu died of famine.[136] Some colonial "pacification" efforts often caused severe famine. The introduction of cash crops such as cotton, and forcible measures to impel farmers to grow these crops, sometimes impoverished the peasantry in many areas, such as northern Nigeria, contributing to greater vulnerability to famine when severe drought struck in 1913. For the middle part of the 20th century, agriculturalists, economists and geographers did not consider Africa to be famine prone – most famines were localized and brief food shortages.

From 1967-1969 large scale famine occurred in Biafra and Nigeria due to a government blockade of the Breakaway territory. It is estimated that 1.5 million people died of starvation due to this famine. Additionally, drought and other government interference with the food supply caused 500 thousand Africans to perish in Central and West Africa.[137] Famine recurred in the 1970s and 1980s, when the west African Sahel suffered drought and famine.[138][139] The Sahelian famine was associated with the slowly growing crisis of pastoralism in Africa, which has seen livestock herding decline as a viable way of life over the last two generations.

Since the start of the 21st century, more effective early warning and humanitarian response actions have reduced the number of deaths by famine markedly. That said, many African countries are not self-sufficient in food production, relying on income from cash crops to import food. Agriculture in Africa is susceptible to climatic fluctuations, especially droughts which can reduce the amount of food produced locally. Other agricultural problems include soil infertility, land degradation and erosion, swarms of desert locusts, which can destroy whole crops, and livestock diseases. The Sahara spreads up to 30 miles per year.[140] The most serious famines have been caused by a combination of drought, misguided economic policies, and conflict. Recent famines in Africa include the 2005–06 Niger food crisis, the 2010 Sahel famine, and in 2012, the Sahel drought put more than 10 million people in the western Sahel at risk of famine, according to the Methodist Relief & Development Fund (MRDF), due to a month-long heat wave.[141]

Cuisine

West African peoples were trading with the Arab world centuries before the influence of Europeans. Spices such as cinnamon were introduced and became part of the local culinary traditions. Centuries later, the Portuguese, French and British further influenced regional cuisines, but only to a limited extent. However, as far as is known, it was European explorers and slaves ships who brought chili peppers and tomatoes from the New World, and both have become ubiquitous components of West African cuisines, along with peanuts, corn, cassava, and plantains. In turn, these slave ships carried African ingredients to the New World, including black-eyed peas and okra. Around the time of the colonial period, particularly during the Scramble for Africa, the European settlers defined colonial borders without regard to pre-existing borders, territories or cultural differences. This bisected tribes and created colonies with varying culinary styles. As a result, it is difficult to sharply define, for example, Senegalese cuisine. Although the European colonists brought many new ingredients to the African continent, they had relatively little impact on the way people cook in West Africa. Its strong culinary traditions lives on despite the influence of colonisation and food migration that occurred long ago.

List of archaeological cultures and sites

- Mousteroid (30,000 BP)[144]

- Bingerville (13,000 BP)[18]

- Bosumpra Cave (11th millennium BCE)[145]

- Iwo Eleru Rockshelter[146] (11,000 BP)[18]

- Kiffian Culture (8400 BCE)[147]

- Ifetedo Rockshelter[146] (9000/7000 BP)[148]

- Dutsen Kongba Rockshelter[146] (6th millennium BCE)[149]

- Konduga (6300 BP)[18]

- Ita Ogbolu Rockshelter (5000/2000 BP)[146]

- Kagoro Rockshelter (5000/2000 BP)[146]

- Tenerian Culture (4300 - 2400 BCE)[150]

- Yengema Cave (2560 BCE)[151]

- Kamabai Rockshelter (2560 BCE)[152]

- Kintampo Complex (2500 - 1400 BCE)[153]

- Karkarichinkat (4500/4200 BP)[154]

- Rim (4000 BP)[151]

- Dhar Tichitt (2000 - 500 BCE)[155]

- Dhar Nema (2000 - 800 BCE)[157]

- Daima (2nd millennium BCE - 16th/17th century CE)[158]

- Sekkiret (2nd millennium BCE)[151]

- Lejja (2000 BCE)[159]

- Gajiganna (1800 - 800 BCE)[160]

- Nok Culture (1500 - 1 BCE)[161]

- Yagala Rockshelter (1070 BCE)[151]

- Kissi (1st millennium BCE - 13th century CE)

- Azelik (1st millennium BCE)[163]

- Dia (9th century BCE)[164]

- Walalde (800 BCE)[165]

- Kursakata (800 BCE)[166]

- Opi (5th century BCE)[146]

- Senegambian Stone Circles (3rd century BCE - 16th century CE)[167]

- Itaakpa Rockshelter (271 BCE)[168]

- Djenne-Djenno (250 BCE - 1100 CE)[169]

- Afikpo Rockshelter[146] (105 BCE)[170]

- Akjoujt (1st century BCE)[151]

- Rop Rockshelter (25 BCE)[171]

- Kirikongo (100 - 1700 CE)[172]

- Hambarketolo (300 - 1000 CE)[173]

- Bura Culture (3rd - 13th century CE)[174]

- Birnin Lafiya (4th - 13th century CE)[175]

- Niani (6th/10th century CE)[176]

- Tondidarou (635/670 CE)[177]

- Gao (700 CE)[178]

- Tegdaoust (810 - 1800 CE)[151]

- Chinguetti (8th century CE)[179]

- Tissalaten (8th - 11th century CE)[173]

- Toyla (890/980 CE)[180]

- Igbo-Ukwu (9th century CE)[181]

- Koumbi Saleh (9th - 15th century CE)[182]

- Kawinza (950/715 CE)[183]

- Begho (1000 CE)[151]

- Walls of Benin (1st millennium CE)[146][184]

- Sungbo's Eredo (10th century CE)[185]

- Diouboye (1000 - 1400 CE)[186]

- Azugi (11th century CE)[173]

- Cekeen Tumuli (11th century CE)[187]

- Ouadane (11th/12th century CE)[188]

- Bandiagara Escarpment (11th - 13th century CE)

- Ruins of Loropeni (11th - 17th century CE)[189]

- Ma'adin Ijafen (1170/1260 CE)[190]

- Ifẹ (12th - 15th century CE)[191]

- Kwiambana (1260 CE)[192]

- Mejiro Rockshelter[146] (1300 CE)[193]

- Benin (13th century CE)[151]

- Durbi Takusheyi (14th - 16th century CE)[194]

- Agbaku Rockshelter (1403 CE)[195]

- Bono Manso (1420 CE)[196]

- Sidi Yahya Mosque (1440 CE)[197]

- Ngazargamu (1488 CE)[198]

- Bonduku (1586 CE)[199]

- Ksar El Barka (1690 CE)[200]

- Jenini (1870 - 1895 CE)[201]

See also

- History of Africa

- History of Benin

- History of Burkina Faso

- History of Cape Verde

- History of Côte d'Ivoire

- History of the Gambia

- History of Ghana

- History of Guinea

- History of Guinea-Bissau

- History of Liberia

- History of Mali

- History of Mauritania

- History of Niger

- History of Nigeria

- History of Saint Helena

- History of Senegal

- History of Sierra Leone

- History of Togo

- Trade & Pilgrimage Routes of Ghana

References

Citations

- Breunig, Peter. 2014. Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context: p. 21.

- Breunig, P. (2014). Nok. African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt: Africa Magna.

- Speth (2010), p. 33

- Ham (2009), p. 79

- American Geophysical Union. "Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started By Changes In Earth's Orbit, Accelerated By Atmospheric And Vegetation Feedbacks". ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- Ehret (2002)

- Tishkoff et al. (2009), p. 1041

- Tishkoff et al., Whole-mtDNA Genome Sequence Analysis of Ancient African Lineages, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 24, no. 3 (2007), pp.757-68.

- Soares, Pedro; Luca Ermini; Noel Thomson; Maru Mormina; Teresa Rito; Arne Röhl; Antonio Salas; Stephen Oppenheimer; Vincent Macaulay; Martin B. Richards (4 June 2009). "Correcting for Purifying Selection: An Improved Human Mitochondrial Molecular Clock". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (6): 82–93. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001. PMC 2694979. PMID 19500773. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Salas, Antonio et al., The Making of the African mtDNA Landscape, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 71, no. 5 (2002), pp. 1082–1111.

- Atlas of the Human Journey: Haplogroup L2 Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Genographic Project, National Geographic.

- Shrine, Daniel; Rotimi, Charles (2018). "Whole-Genome-Sequence-Based Haplotypes Reveal Single Origin of the Sickle Allele during the Holocene Wet Phase". American Journal of Human Genetics. 102 (4): 547–556. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.003. PMC 5985360. PMID 29526279.

- Trombetta, Beniamino (2015). "Phylogeographic Refinement and Large Scale Genotyping of Human Y Chromosome Haplogroup E Provide New Insights into the Dispersal of Early Pastoralists in the African Continent". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (7): 1940–1950. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv118. PMC 4524485. PMID 26108492.

- Tishkoff et al. (2009), p. 1043

- Sims, Lynn; Garvey, Dennis; Ballantyne, Jack (2007). "Sub-Populations Within the Major European and African Derived Haplogroups R1b3 and E3a Are Differentiated by Previously Phylogenetically Undefined Y-SNPs". Human Mutation. 28 (1): 97. doi:10.1002/humu.9469. PMID 17154278.

- Oshita, edited by Celestine Oyom Bassey & Oshita O. (2010). Governance and Border Security in Africa. Lagos: Malthouse Press Ltd. for the University of Calabar Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-978-8422-07-5. Retrieved 23 August 2014.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Ian Shaw, Robert Jameson. A Dictionary of Archaeology. p28. Wiley-Blackwell, 2002. ISBN 0-631-23583-3

- McIntosh, Susan (2001). "West African Late Stone Age". Encyclopedia of Prehistory Volume 1: Africa. pp. 319–322. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1193-9_27. ISBN 978-0-306-46255-9.

- Bellwood, Peter (10 November 2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 100. ISBN 9781118970591.

- Simon Bradley, A Swiss-led team of archaeologists has discovered pieces of the oldest African pottery in central Mali, dating back to at least 9,400BC Archived 2012-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, SWI swissinfo.ch – the international service of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SBC), 18 January 2007

- Scarcelli, Nora (2019). "Yam genomics supports West Africa as a major cradle of crop domestication" (PDF). Science Advances. 5 (5): eaaw1947. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.1947S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw1947. PMC 6527260. PMID 31114806.

- Ehret (2002), pp. 82–84

- "Stone Age Graveyard reveals Lifestyles of a 'Green Sahara': Two Successive Cultures Thrived Lakeside". UChicagoNews. University of Chicago Office of Communications.

- Ehret (2002), pp. 64–75

- Ehret, Christopher (2001). Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History. Temple University Press. p. 235. ISBN 9781566398329.

- Blench, Roger. "Africa over the last 12000 years: how we can interpret the interface of archaeology, linguistics and genetics (Draft)". Academia. University of Cambridge.

- MacEachern, Scott (2012). "The Holocene history of the southern Lake Chad Basin: archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence". African Archaeological Review. 29 (2–3): 253–271. doi:10.1007/s10437-012-9110-3.

- Breunig, Peter; Neumann, Katharina; Neer, Wim (1996). "New research on the Holocene settlement and environment of the Chad Basin in Nigeria". African Archaeological Review. 13 (2): 111–145. doi:10.1007/BF01956304.

- MacDonald, Kevin (1997). "Korounkorokalé revisited: The Pays Mande and the West African microlithic technocomplex". African Archaeological Review. 14 (3): 161–200. doi:10.1007/BF02968406.

- Ehret (2002), pp. 136-137

- González-Fortes, G.; Tassi, F.; Trucchi, E.; Henneberger, K.; Paijmans, J.; Díez-del-Molino, D.; Schroeder, H.; Susca, R.; Barroso-Ruíz, C.; Bermudez, F.; Barroso-Medina, C.; Bettencourt, A.; Sampaio, H.; Grandal-d'Anglade, A.; Salas, A.; de Lombera-Hermida, A.; Valcarce, R.; Vaquero, M.; Alonso, S.; Lozano, M.; Rodríguez-Alvarez, X.; Fernández-Rodríguez, C.; Manica, A.; Hofreiter, M.; Barbujani, G. (2019). "A western route of prehistoric human migration from Africa into the Iberian Peninsula". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1895): 20182288. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2288. PMC 6364581. PMID 30963949.

- Collins & Burns (2007), pp. 79-80

- Iliffe (2007), pp. 49–50

- Collins & Burns (2007), p. 78

- Mayor, Anne. "Ceramic Traditions and Ethnicity in the Niger Bend, West Africa". ResearchGate. University of Geneva.

- Childs, S Terry and Killick, David. Indigenous African Metallurgy: Nature and Culture. In: Annual Review of Anthropology 1993. 22:317-37. p. 320

- Miller, Duncan E.; Van Der Merwe, Nickolaas J. (March 1994). "Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa". Journal of African History. 35 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0021853700025949.

- Stuiver, Minze; Van Der Merwe, Nicholas J. (February 1968). "Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa". Current Anthropology. 9 (1): 48–62. doi:10.1086/200878. Lay summary.

- Eze–Uzomaka, Pamela. "Iron and its influence on the prehistoric site of Lejja". Academia.edu. University of Nigeria,Nsukka, Nigeria. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Bocoum, Unesco. Ed. by Hamady (2004). The Origins of Iron Metallurgy in Africa : new light on its antiquity ; West and Central Africa (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 92-3-103807-9. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 51–59.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (6 November 2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9030-6.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 53–54.

- Duncan E. Miller and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa' Journal of African History 35 (1994) 1-36

- Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' Current Anthropology 1968. Tylecote 1975 (see below)

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 51–59.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 53–54.