Taghaza

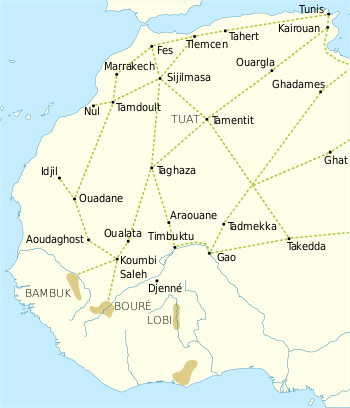

Taghaza (also Teghaza) is an abandoned salt-mining centre located in a salt pan in the desert region of northern Mali. It was an important source of rock salt for West Africa up to the end of the 16th century when it was abandoned and replaced by the salt-pan at Taoudenni which lies 150 km (93 mi) to the southeast. Salt from the Taghaza mines formed an important part of the long distance trans-Saharan trade. The salt pan is located 857 km (533 mi) south of Sijilmasa (in Morocco), 787 km (489 mi) north-northwest of Timbuktu (in Mali) and 731 km (454 mi) north-northeast of Oualata (in Mauritania).

Taghaza | |

|---|---|

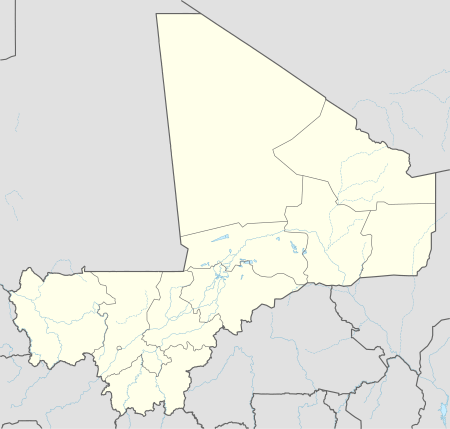

Taghaza Location within Mali | |

| Coordinates: 23°36′N 5°00′W | |

| Country | Mali |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

Early Arabic sources

The Taghaza mines are first mentioned by name (as Taghara) in around 1275 by the geographer al Qazwini who spent most of his life in Iraq but obtained information from a traveller who had visited the Sudan.[1] He wrote that the town was situated south of the Maghreb near the ocean and that the ramparts, walls and roofs of the buildings were made of salt which was mined by slaves of the Masufa, a Berber tribe, and exported to the Sudan by a caravan that came once a year.[2] A similar description had been given earlier by Al-Bakri in 1068 for the salt mines at a place that he called Tantatal, situated twenty days from Sijilmasa.[3] It is possible these were the same mines.[4]

In 1352 the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta arrived in Taghaza after a 25-day journey from Sijilmasa on his way across the Sahara to Oualata to visit the Mali Empire.[5][6] According to Ibn Battuta, there were no trees, only sand and the salt mines. Nobody lived in the village other than the Musafa slaves who dug for the salt and lived on dates imported from Sijilmasa and the Dar'a valley, camel meat and millet imported from the Sudan. The buildings were constructed from slabs of salt and roofed with camel skins. The salt was dug from the ground and cut into thick slabs, two of which were loaded onto each camel. The salt was taken south across the desert to Oualata and sold. The value of the salt was chiefly determined by the transport costs. Ibn Battuta mentions that the value increased fourfold when transported between Oualata and the Malian capital.[7] In spite of the meanness of the village, it was awash in Malian gold. Ibn Battuta did not enjoy his visit; he found the water brackish and the village full of flies.[5] He goes on to say, "For all its squalor, qintars of qintars of gold dust are traded in Taghaza."[8]

The salt mines became known in Europe not long after Ibn Battuta's visit as Taghaza was shown on the Catalan Atlas of 1375 on the trans-Saharan trade route linking Sijilmasa and Timbuktu.[6]

Alvise Cadamosto learned in 1455 that Taghaza salt was taken to Timbuktu and then onto Mali. It was then carried "a great distance" to be bartered for gold.[9]

In around 1510 Leo Africanus spent 3 days in Taghaza. In his Descrittione dell’Africa he mentions that the location of the mines, 20 days journey from a source of food, meant that there was a risk of starvation. At the time of Leo's visit, Oualata was no longer an important terminus for the trans-Saharan trade and salt was instead taken south to Timbuktu. Like Ibn Battuta before him, Leo complained about the brackish well water.[10]

Sixteenth century

At some date Taghaza came under the control of the Songhai Empire which had its capital at the city of Gao on the Niger River 970 km (600 mi) across the Sahara. Al-Sadi in his Tarikh al-Sudan chronicles the efforts of the Moroccan rulers of the Saadi dynasty to wrestle control of the mines from the Songhai during the 16th century. In around 1540 the Saadian Sultan Ahmad al-Araj asked the Songhai leader Askia Ishaq I to cede the Taghaza mines. According to al-Sadi, Askia Ishaq I responded by sending men to raid a town in the Dara valley as a demonstration of Songhai power.[11] Then in 1556-7 Sultan Muhammed al-Shaykh occupied Taghaza and killed the Askia's representative.[12] However the Tuareg shifted the production to another mine called Taghaza al-ghizlan (Taghaza of the gazelles). On his succession in 1578 Ahmad al-Mansur asked for the tax revenues from Taghaza but Askiya Dawud responded instead with a generous gift of 47 kg of gold.[13] In 1586 a small Saadian force of 200 musketeers again occupied Taghaza[14] and the Tuareg moved to yet another site – probably Taoudeni.[15] Finally, a new demand by Ahmad al-Mansur in 1589–90 was met with defiance by Askiya Ishak II. This provided the pretext for Ahmad al-Mansur to send an army of 4,000 mercenaries across the Sahara led by the Spaniard Judar Pasha.[16] The defeat of the Songhai in 1591 at the Battle of Tondibi led to the collapse of their empire. After the conquest Taghaza was abandoned and Taoudenni, situated 150 km (93 mi) to the southeast and thus nearer to Timbuktu, took its place as the region's key salt producer.

In 1828 the French explorer René Caillié stopped at Taghaza on his journey across the Sahara from Timbuktu. He was travelling with a large caravan that included 1,400 camels transporting slaves, gold, ivory, gum and ostrich feathers.[17] At that date the ruins of houses constructed of salt bricks were still clearly visible.[18]

Ruins

At Taghaza there are ruins of two different settlements, one on either side of the ancient salt lake (or sabkha). They are separated by a distance of 3 km.[19] The larger more westerly settlement extended over an area of approximately 400 m by 200 m.[20] All the houses, except the mosque, were aligned in a northwest to southeast direction, perpendicular to the prevailing wind. The houses in the more easterly settlement were aligned in the same manner and occupied an area of 200 m by 180 m. The reason for the dual settlements is not known but could be connected with Taghaza's service both as a salt mine and as a stopping point on an important trans-Saharan trade route.[21]

Climate

Taghaza has a hyper-arid hot desert climate (BWh). It is one of the driest places on earth and one of the hottest during summer. The average high temperature in July is 48.2 °C (118.8 °F), which is higher than Death Valley.

| Climate data for Teghaza | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.2 (77.4) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

41.3 (106.3) |

45.7 (114.3) |

48.2 (118.8) |

46.8 (116.2) |

43.5 (110.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

30.5 (86.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

35.1 (95.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

22.8 (73.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

19.3 (66.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

3 (0.1) |

4 (0.2) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

11 (0.3) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[22] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Judar Pasha

- Saadi Dynasty

Notes

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 176, 178; Mauny 1961, p. 330; Hunwick 2000, p. 89.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 178.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 76.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 399 note 3.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 282.

- Mauny 1961, p. 330.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 414 note 5. The location of the Malian capital is uncertain.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 281. ISBN 9780330418799.

- Wilks,Ivor. Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (1997). Bakewell, Peter (ed.). Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Leo Africanus 1896, pp. 800–801 Vol. 3.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 142.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 151.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 155.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 166.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 167.

- Kaba 1981; Hunwick 1999, pp. 309–310.

- Caillié 1830, p. 106 Vol. 2.

- Caillié 1830, p. 128 Vol. 2. Caillié uses the spelling Trasas or Trarzas. See Caillié 1830, pp. 329–330 Vol. 2.

- Mauny 1961, p. 369 Fig. 67.

- Mauny 1961, pp. 485–487.

- Mauny 1961, p. 487.

- "Climate: Teghaza". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

References

- Caillié, René (1830), Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo; and across the Great Desert, to Morocco, performed in the years 1824-1828 (2 Vols), London: Colburn & Bentley. Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Hunwick, John O. (2000), "Taghaza", Encyclopaedia of Islam Volume 10 (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill, p. 89, ISBN 90-04-11211-1.

- Kaba, Lansiné (1981), "Archers, musketeers, and mosquitoes: The Moroccan invasion of the Sudan and the Songhay resistance (1591-1612)", Journal of African History, 22 (4): 457–475, doi:10.1017/S0021853700019861, JSTOR 181298, PMID 11632225.

- Leo Africanus (1896), The History and Description of Africa (3 Vols), Brown, Robert, editor, London: Hakluyt Society. Internet Archive: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3. The original text of Pory's 1600 English translation together with an introduction and notes by the editor.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York: Marcus Weiner Press, ISBN 1-55876-241-8. First published in 1981 by Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22422-5.

- Mauny, Raymond (1961), Tableau géographique de l'ouest africain au moyen age (in French), Dakar: Institut français d'Afrique Noire, OCLC 6799191. Page 329 has a map showing the sabkha and the two settlements. Page 486 has plans of the settlements.

Further reading

- Monod, Théodore (1938), "Teghaza, La ville en sel gemme (sahara occidental)", La Nature (in French) (3025 15-May-1938): 289–296.