Futa Tooro

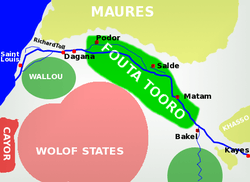

Futa Toro (Wolof and Fula: Fuuta Tooro; French: Fouta-Toro), often simply the Futa, is a semidesert region around the middle run of the Senegal River. This region is along the border of Senegal and Mauritania. It is well watered and fertile close to the river, but the interior parts of the region away from the river is porous, dry and infertile.[1] This region is historically significant for the Islamic theocracies, Fulani states, jihad armies and migrants for Fouta Djallon that emerged from here.[2][3]

.png)

Geography

The Futa Toro stretches for about 400 kilometers, but of a narrow width of up to 20 kilometers on either side of the Senegal River.[4] The western part is called Toro, the central and eastern parts called Futa. The central portion include Bosea, Yirlabe Hebbyabe, Law and Hailabe provinces. The eastern Futa includes Ngenar and Damga provinces. The region north and east to Futa Toro is barren Sahara. Historically, each of the Futa Toro geographical provinces were fertile pockets of land due to the waalo flood plains present, and the control of this resource was driven by kin-based families. The long stretch meant the whole region was divided among many families, and the succession property rights from one generation to next led to many family disputes, political crises and conflicts.[4]

History

The word Futa was a general name the Fulbe gave to any area they lived in, while Toro was the actual identity of the region for its inhabitants. The people of the kingdom spoke Pulaar, a dialect of the greater Fula languages spanning West Africa from Senegal to Cameroon. They identified themselves by the language giving rise to the name Haalpulaar'en meaning those who speak Pulaar. The Haalpulaar'en are also known as Toucouleurs (var. Tukolor), a name derived from the ancient state of Tekrur.

Islam arrived in the region in its early stages. The Toucouleur people of this region converted by the 11th century.[5] The region saw many Islamic powers thereafter. The state of Denanke (1495/1514-1776) saw the origin of the modern Tukolor people. Migrations of the Fulbe left states in Futa Toro and Futa Jallon to the south.

The rise of the Imamate of Futa Toro in 1776 sparked a series of Islamic reform movements and jihads.[6][2] Small clans of educated Fula Sufi Muslims (the Torodbe) seized power in states across West Africa.

In the 1780s Abdul Kader became almaami (religious leader or imam) but his forces were unable to spread revolution to the surrounding states.[7]

The Imamate of Futa Toro later became the inspiration and the prime recruiting ground for the jihads of Toucouleur conqueror al-Hajj Umar Tall and anti-colonial rebel al-Hajj Mahmadu Lamine. Despite resistance, the Futa Toro was firmly in the hands of French Colonial forces moving from modern Senegal by 1900. Upon independence, the region's heart, the southern bank of the Senegal River was retained by Senegal. The north bank became part of Mauritania.

The great modern Senegalese musician and worldbeat star Baaba Maal comes from the town of Podor in the Futa Toro.

See also

- Imamate of Futa Toro

- Fulani people

- Toucouleur people

References

- Fouta, Senegal, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Sohail H. Hashmi (2012). Just Wars, Holy Wars, and Jihads: Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Encounters and Exchanges. Oxford University Press. pp. 247–249. ISBN 978-0-19-975504-2.

- Boubacar Barry (1998). Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-521-59226-0.

- Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 500–501. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9

- Nehemia Levtzion; Randall Pouwels (2000). The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-8214-4461-0.

- http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e688?_hi=3&_pos=1