History of the Kingdom of Dahomey

The History of the Kingdom of Dahomey spans 300 years from around 1600 until 1904 with the rise of the Kingdom of Dahomey as a major power on the Atlantic coast of modern-day Benin until French conquest. The kingdom became a major regional power in the 1720s when it conquered the coastal kingdoms of Allada and Whydah. With control over these key coastal cities, Dahomey became a major center in the Atlantic Slave Trade until 1852 when the British imposed a naval blockade to stop the trade. War with the French began in 1892 and the French took over the Kingdom of Dahomey in 1894. The throne was vacated by the French in 1900, but the royal families and key administrative positions of the administration continued to have a large impact in the politics of the French administration and the post-independence Republic of Dahomey, renamed Benin in 1975. Historiography of the kingdom has had a significant impact on work far beyond African history and the history of the kingdom forms the backdrop for a number of novels and plays.

| History of Benin |

|---|

|

| History of the Kingdom of Dahomey |

| Early history |

|

| Modern period |

|

|

History

Before the Kingdom of Dahomey

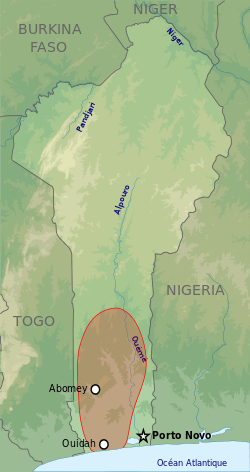

Prior to the centralization of the kingdom of Dahomey, the evidence suggests that the Abomey plateau was settled by a number of small tribes, commonly known as the Gedevi. However, because of a lack of resources and access to the key trade routes in the region, the plateau was very poor compared to the surrounding areas.[1] To the east of the Abomey plateau, the Oyo Empire (in present-day Nigeria) was at the peak of its power and exercised some hegemony over the tribes in the area. To the south, there were two prominent kingdoms, Allada and the Whydah, which had power along the Atlantic coast.[1] The coastal area had come in contact with the Portuguese in the 15th century, but significant trade did not start until 1533 when the Portuguese and the city of Grand-Popo signed a trade agreement.[2]

Founding

There are a number of different folk stories about the founding of the Kingdom of Dahomey. Most scholars believe many of these stories were created or exaggerated in the 18th century to promote the legitimacy of the Dahomey royal regimes at the time and thus may be based only loosely on actual events.[3]

The most common founding myth traces the establishment of the kingdom to the royal lineage of Allada. According to this story, there was a Fon prince named Agassu in the city of Tado who tried to become king but lost the struggle and took over the city of Allada instead. Around 1600, two (in some versions three) princes in Agassu's lineage fought over who would be the ruler of Allada.[1] It was decided that both princes would leave the town and found new kingdoms with Teagbanlin going south and founding the city that would become Porto-Novo and Do-Aklin moving to the Abomey plateau to the north (Porto-Novo and the Kingdom of Dahomey remained rivals for much of history).[3] Do-Aklin's son Dakodonu was granted permission to settle in the area by the Gedevi chiefs in Abomey. However, when Dakodonu requested additional land from a prominent chief named Dan the relationship grew hostile. The chief responded to Dakodonu, with sarcasm, "Should I open up my belly and build you a house in it?" Dakodonu killed Dan on the spot and ordered that his new palace be built on the site and derived the kingdom's name from the incident (this may be a false etymology[4]): Dan=chief, xo=Belly, me=Inside of.[3]

Rise and expansion (1600-1740)

| Kingdom of Dahomey Timeline | |

|---|---|

| c. 1600 AD | According to oral tradition, Dakodonou establishes palace in Abomey. |

| 1724-1727 AD | Agaja conquers Allada and Whydah. |

| 1730 AD | Dahomey loses war with the Oyo Empire becoming a tributary. |

| 1823 AD | King Ghezo defeats Oyo in war and ends tributary status of Dahomey. |

| 1851-1852 AD | British put naval blockade on Dahomey ports stopping the slave trade. |

| 1892-1894 AD | Second Franco-Dahomean War leads to colonization of Kingdom of Dahomey. |

| 1900 AD | French exile Agoli-agbo formally ending the Kingdom of Dahomey. |

The empire was established in about 1600 by the Fon people who had recently settled in the area (or were possibly a result of intermarriage between the Aja people and the Gedevi). The Palace in Abomey was established in the early 17th century. The foundational king of the Kingdom of Dahomey is often considered Houegbadja (c.1645-1685) who built the Royal Palaces of Abomey and began raiding and taking over towns outside of the Abomey plateau.[1][4] At the same time, the slave trade began increasing in size in the coastal region through the Kingdom of Whydah and Allada and trade with the Portuguese, Dutch, and British. The Dahomey Kingdom became known to European traders at this time as a major source of slaves in the slave trade at Allada and Whydah.[5]

King Agaja, grandson of Houegbadja, came to the throne in 1718 and began significant expansion of the Kingdom of Dahomey. By 1720, King Agaja repudiated the kingdom's allegiance to Allada and began increasing military activity throughout the region. In 1724, Agaja offered his military to help with a succession struggle within Allada.[5] However, he turned his forces on the army of Allada and took over the city, relocating his capital from Abomey to Allada.[3] In 1727, Agaja took over the city of Whydah and thus became the primary force on a major part of the coast.[1] In 1729, Agaja began war against the Oyo Empire with a number of cross-border raids.[6] During the war, the royal family of Whydah returned to the throne forcing Agaja to fight to reclaim the city. He moved much of his army with a significant portion in the back composed of women dressed like male warriors (this is possibly the beginning of the Dahomey Amazons). The Whydah royal family had assumed that the Dahomey army had been weakened in the war with Oyo and, upon seeing such a large force, fled from the city.[6] In 1730 the war with Oyo ended and Dahomey retained domestic control but became a tributary of the Oyo empire.[5] By the end of Agaja's reign, the Kingdom of Dahomey occupied significant area, particularly the crucial coastal slave trade cities. At the same time, Agaja created much of the administrative apparatus of the kingdom and instituted the key ceremony of the Annual Customs, or Xwetanu in Fon.

Regional power (1740-1852)

Following the death of Agaja in 1740, the empire was defined by significant political struggle (although limited largely to within the palace walls) and deepening engagement with the slave trade. There was a significant succession fight after Agaja's death when the recognized heir was passed over for Tegbessou (who ruled from 1740-1774).[3] Tegbessou moved the capital city back to Abomey but had to deal with a number of different factions in the powerful members of the kingdom and in keeping conquered territories loyal.[3] At the same time, the empire continued slave raids throughout the region and became a major supplier to the Atlantic slave trade. In the late 18th century, Oyo put pressure onto Dahomey to reduce its participation in the slave trade (largely to protect its own slave trade) and Dahomey complied by limiting some of the slave trade.[7] However, even with this, the empire was a significant player in the slave trade supplying up to 20% of the total slave trade and providing the largest portion of revenue for the king.[8]

In 1818, King Ghezo (reign 1818-1858) came to the throne by forcibly replacing his older brother Adandozan.[2] Crucial in Ghezo's rise to power was the financial and military assistance of Francisco Félix de Sousa, a prominent Brazilian slave trader located in Whydah. As a result, Ghezo named de Sousa the chacha or viceroy of trade in Whydah providing him with significantly more power and money (the title chacha remains an important honorary position in Whydah to this day). In 1823, Ghezo led armies against Oyo and was this time able to end the tributary status of Dahomey and permanently weaken Oyo.[5]

Suppression of the slave trade (1852-1880)

Two major changes occurred in the 1840s and 1850s which significantly altered politics in Dahomey. First, the British who had been a major purchaser of slaves began taking an active stance in abolishing the slave trade in the 1830s. They sent multiple diplomatic parties to Ghezo to try to convince him to end Dahomey's participation in the trade, all of these were rebuffed with Ghezo worried of the political consequences of ending such trade.[2] Second, the city of Abeokuta was founded in 1825 and rose to prominence as a safe haven for people to be safe from the slave raids by Dahomey. In 1844, Dahomey and Abeokuta went to war and Abeokuta was victorious. Other violence in the early 1850s further cemented Abeokuta's challenge to Dahomey's economic control in the region.[7]

Internally, the pressure resulted in a number of changes. Ghezo rejected British requests for ending the slave trade, but at the same time began expanding significantly the palm oil trade as an economic alternative.[2] Politically, the debate became centered around two political factions: the Elephant and the Fly. The Elephant, connected with Ghezo, high-profile political leaders, and the creole slave traders like the family of De Sousa, pushed for continued activity in the slave trade and resistance to British pressure. The Fly faction, in contrast, was a loose collection of palm oil producers and some chieftains, which supported accommodation with Abeokuta and the British in order to expand palm oil trade.[7] At the policy and war debates held at the Annual Customs these two factions held a number of tense discussions about the future of the Kingdom of Dahomey.[7]

In 1851–1852, the British imposed a naval blockade on the ports of Dahomey in order to force them to end the slave trade. In January 1852, Ghezo accepted a treaty with the British ending the export of slaves from Dahomey.[2] In the same year and the following one, Ghezo suspended large-scale military campaigns and human sacrifice in the kingdom. However political pressure contributed to the resumption of slave trading and large scale military action in 1857 and 1858.[2] Ghezo was assassinated by a sniper associated with Abeokuta and large scale warfare between the two states resumed in 1864.[7] This one ended again in the favor of Abeokuta and the result was that the slave trade could not be significantly reestablished to its 1850 level. The power of slave traders in the empire decreased and the palm oil trade became a more significant part of the economy.[7]

European colonization (1880-1900)

Dahomey's control of key coastal cities continued and made the area a crucial location in the European scramble for Africa.[9] In 1878, the Kingdom of Dahomey agreed to the French making the city of Cotonou into a protectorate; although taxation of the King of Dahomey was to remain in effect. In 1883, the French received similar concessions over Porto-Novo, a traditional rival of Dahomey along the coast.[9]

In 1889, King Glele died and his son Béhanzin came to power and immediately became quite hostile to the French in negotiations. Béhanzin renounced the treaty with France providing them with the city of Cotonou and began raiding the possessions. The hostility hit a high point when Béhanzin began conducting slave raids in French protectorates along the coast, namely Grand-Popo, in 1891. That year, the French military decided that a military takeover was the only solution and placed General Alfred-Amédée Dodds in charge of the operation to commence in 1892.

The Franco-Dahomean War lasted from 1892 until January 1894 when Dodds captured the city of Abomey (January 15) and King Béhanzin (January 25). Notable during the war was the defeat of the Dahomey Amazons in November 1892. Dodds named Agoli-agbo the new king of Dahomey, largely because he was seen as the most malleable of the alternatives, and exiled Béhanzin to French possessions in the Caribbean.[9] The French began changing key aspects of administration and politics in the Kingdom of Dahomey. In 1899, the French instituted a new poll tax which was highly unpopular and Agoli-Agbo opposed the tax causing serious political problems in the protectorate. As a result, on February 17, 1900, the French deposed Agoli-Agbo and ended the Kingdom of Dahomey.[9] The French though brought together many key members of the kingdom as the chiefs of cantons. French Dahomey included the Kingdom of Dahomey, with Porto-Novo and an area to the north of loose tribal control.[10]

Agoli-Agbo remained exiled from 1900 until 1910 when the French administration decided to allow him to return to the area because of his key role in Fon ancestor worship and ceremonies. He was not allowed to reside in Abomey or travel freely, but was allowed to visit Abomey to perform ceremonial functions during the Annual Customs by the French administration.[9]

Political legacy

French Dahomey administration remained over the area from 1900 until 1960 when the country gained independence and took the name Republic of Dahomey. In 1975, the name of the country was changed from Republic of Dahomey to Benin. The King of Dahomey remains an important ceremonial position and continued through both French administration and independence. Since 2000, there has been a struggle over the position with Agoli-Agbo III and Houedogni Behanzin holding rival claims to the throne.[11]

The political and economic hierarchies of Dahomey have remained crucial in post-independence Dahomey and Benin. One of the key leaders in the triumvirate which dominated politics in the country from 1960 until 1972 was Justin Ahomadégbé-Tomêtin, twice the head of state of the country, who garnered significant political power through his connection to the royal lineage of Dahomey.[10] The descendants of Francisco Félix de Sousa remain very important political leaders in Benin to this day including Colonel Paul-Émile de Souza (Benin head of state 1969-1970), Isidore de Souza (President of National Assembly of Benin 1990-1991), and others.[12]

Kojo Tovalou Houénou (1887–1936), who claimed to be a prince of Dahomey but had lived most of his life in France, became a major critic of the French colonial empire and founded the Ligue Universelle pour la Défense de la Race Noire to push for recognition of Africans as full citizens of the French state.[13]

Historiography

European historiography of Dahomey has been significant for its use in debates about the morality of the slave trade and for its importance to fields outside African history. Many of the early histories and descriptions were written by slave traders and the conclusions were that the slave trade was a process of freeing the population from the highly militarized, very brutal, and despotic Kingdom of Dahomey. William Snelgrave and Archibald Dalzel wrote key histories and memoirs of Dahomey presenting the case for the slave trade to save the population from human sacrifice. Abolitionist historians, in contrast, argued that the brutality of the Dahomey state was the result of the slave trade itself.[5] Dahomey was thus portrayed with a host of very negative stereotypes, with significant exaggeration, by European historians in the 18th and 19th century.[4] With increasing debates about the morality or immorality of the slave trade, Dahomey became a key aspect of the debate with significant attention.[5]

The key role of Dahomey with the slave trade had a significant impact on a range of other scholars. Philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel used the funeral ceremonies after the death of the King of Dahomey in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1837). Karl Polanyi's last written book Dahomey and the Slave Trade (1966) explored the economic relationships in the kingdom.[5]

In popular culture

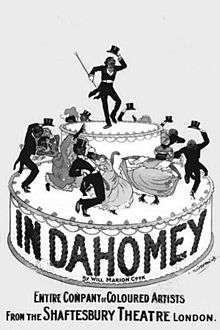

The Kingdom of Dahomey has been depicted in a number of different literary works of fiction or creative nonfiction. In Dahomey (1903) was a successful Broadway musical, the first full-length Broadway musical written entirely by African Americans, in the early 20th century. Novelist Paul Hazoumé's first novel Doguicimi (1938) was based on decades of research into the oral traditions of the Kingdom of Dahomey during King Ghezo. American novelist Frank Yerby published a historical novel set partially in Dahomey titled The Man From Dahomey (1971). British author George MacDonald Fraser published Flash for Freedom! (1971), the third novel in The Flashman Papers series that was set in Dahomey during the slave trade. Bruce Chatwin's historical novel The Viceroy of Ouidah (1980) is largely based around Francisco Félix de Sousa, the slave trader who helped bring King Ghezo to power. The book resulted in the film adaptation Cobra Verde (1987) by Werner Herzog. Ben Okri's novel The Famished Road (1991), which won the Man Booker Prize, tells the story of a person caught in the slave trade through Dahomey.

Béhanzin's resistance to the French has been central to a number of works. Jean Pliya's first play Kondo le requin (1967), winner of the Grand Prize for Black African History Literature, tells the story of Béhanzin's resistance. Maryse Condé's novel The Last of the African Kings (1992) similarly focuses on Béhanzin's resistance and his exile to the Caribbean.[14]

References

- Halcrow, Elizabeth M. (1982). Canes and Chains: A Study of Sugar and Slavery. Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishing.

- Law, Robin (1997). "The Politics of Commercial Transition: Factional Conflict in Dahomey in the Context of the Ending of the Atlantic Slave Trade" (PDF). The Journal of African History. 38 (2): 213–233. doi:10.1017/s0021853796006846.

- Monroe, J. Cameron (2011). "In the Belly of Dan: Space, History, and Power in Precolonial Dahomey". Current Anthropology. 52 (6): 769–798. doi:10.1086/662678.

- Bay, Edna (1998). Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. University of Virginia Press.

- Law, Robin (1986). "Dahomey and the Slave Trade: Reflections on the Historiography of the Rise of Dahomey". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 237–267. doi:10.1017/s0021853700036665.

- Alpern, Stanley B. (1998). "On the Origins of the Amazons of Dahomey". History in Africa. 25: 9–25. doi:10.2307/3172178.

- Yoder, John C. (1974). "Fly and Elephant Parties: Political Polarization in Dahomey, 1840-1870". The Journal of African History. 15 (3): 417–432. doi:10.1017/s0021853700013566.

- Heywood, Linda M.; John K. Thornton (2009). "Kongo and Dahomey, 1660-1815". In Bailyn, Bernard & Patricia L. Denault (ed.). Soundings in Atlantic history: latent structures and intellectual currents, 1500–1830. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Newbury, C.W. (1959). "A Note on the Abomey Protectorat". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 29 (2): 146–155. doi:10.2307/1157517.

- Decalo, Samuel (1973). "Regionalism, Politics, and the Military in Dahomey". The Journal of Developing Areas. 7 (3): 449–478.

- Araujo, Ana Lucia (2010). Public Memory of Slavery: Victims and Perpetrators in the South Atlantic. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press.

- Soumonni, Elisee (2001). "Some Reflections on the Brazilian Legacy in Dahomey". In Kristin Man and Edna Bay (ed.). Rethinking the African Diaspora. New York: Frank Cass. pp. 62–71.

- Stokes, Melvyn (2009). "Kojo Touvalou Houénou: An Assessment". Transatlantica (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Encyclopedia of African Literature (Gikandi, Simon ed.). London: Routledge. 2003.

Further reading

- Manning, Patrick (2004). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-152307-3.