Samori Ture

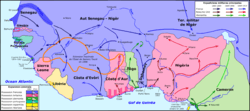

Samori Ture (c. 1830 – June 2, 1900), also known as Samori Toure, Samory Touré, or Almamy Samore Lafiya Toure, was a Muslim cleric, a slave raider, and the founder and leader of the Wassoulou Empire, an Islamic empire that was in present-day north and south-eastern Guinea and included part of north-eastern Sierra Leone, part of Mali, part of northern Côte d'Ivoire and part of southern Burkina Faso. Samori Ture was a deeply religious Muslim of the Maliki jurisprudence of Sunni Islam.

| Samory Toure | |

|---|---|

| |

| Emperor of the Wassoulou Empire | |

| Reign | 1878 - 1898 |

| Predecessor | position established |

| Successor | position abolished |

| Born | c. 1830 Manyambaladugu |

| Died | June 2, 1900 (aged 69/70) Gabon |

| House | Dyula |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Ture resisted French colonial rule in West Africa from 1882 until his capture in 1898. Samori Ture was the great-grandfather of Guinea's first president, Ahmed Sékou Touré.

Early life and career

Samori Ture was Koniaka-malinké, born in c. 1830 in Manyambaladugu (in the Konyan/ Beyla region of what is now south-eastern Guinea), the son of Dyula traders. He grew up as West Africa was being transformed through growing contacts and trade with the Europeans in commodities, artisan goods and products. European trade made some African trading states rich. The trade in firearms changed traditional West African patterns of warfare and heightened the severity of conflicts, increasing the number of fatalities. Early in his life, Ture converted to Islam.[1][2]

In 1848, Samori's mother was captured in the course of war by Séré-Burlay, of the Cissé clan. He then went to exchange himself for his mother as a result of his love for her. After arranging his mother's freedom, Samori entered into service to the Cissé, and learned to handle firearms. According to tradition, he remained "seven years, seven months, seven days" before fleeing with his mother.

He joined the Bérété army, the enemies of the Cissé, for two years before rejoining his people, the Kamara. Named Kélétigui (war commander) at Dyala in 1861, Ture took an oath to protect his people against both the Bérété and the Cissé. He created a professional army and placed close relations, notably his brothers and his childhood friends, in positions of command.

Expansion

In 1864, El Hadj Umar Tall died; he had founded the Toucouleur Empire that dominated the Upper Niger River. As the Toucouleur state lost its grip on power, generals and local rulers vied to create states of their own.

By 1867, Ture was a full-fledged war commander, with an army based at Sanankoro in the Guinea Highlands, on the Upper Milo, a Niger River tributary. Ture had two major goals: to create an efficient, loyal fighting force equipped with modern firearms,[3] and to build a stable state.

By 1876, Samori was importing breech-loading rifles through the British colony of Freetown in Sierra Leone. He conquered the Buré gold-mining district (now on the border between Mali and Guinea) to bolster his financial situation. By 1878 he was strong enough to proclaim himself faama (military leader) of his Wassoulou Empire. He made Bissandugu his capital and began political and commercial exchanges with the neighbouring Toucouleur.

In 1881, after numerous struggles, Ture secured control of the key Dyula trading centre of Kankan, on the upper Milo River. Kankan was a centre for the trade in kola nuts, and was well sited to dominate the trade routes in all directions. By 1881, the Wassoulou Empire extended through the territory of present-day Guinea and Mali, from what is now Sierra Leone to northern Côte d'Ivoire.

Ture conquered the numerous small tribal states around him and worked to secure his diplomatic position. He opened regular contacts with the British colonial administration in Sierra Leone. He also built a working relationship with the Fulbe (Fula) Imamate of Futa Jallon.

First battles with the French

The French began to expand in West Africa in the late 1870s, pushing eastward from Senegal to reach the upper reaches of the Nile in what is now Sudan. They sought to drive south-east to link up with their bases in Côte d'Ivoire. These actions put them directly into conflict with Ture.

In February 1882, a French expedition attacked one of Ture's armies that was besieging Keniera. Ture drove off the French, but he was alarmed at the discipline and firepower which their troops commanded.

He approached dealing with the French in several ways. First, he expanded south-westward to secure a line of communication with Liberia. In January 1885 he sent an embassy to Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone and a Crown Colony of the British, offering to put his kingdom under British protection. The British did not want to confront the French at this time, but they allowed Ture to buy large numbers of modern repeating rifles.

When an 1885 French expedition under Col. A. V. A. Combes attempted to seize the Buré gold fields, Ture counter-attacked. Dividing his army into three mobile columns, he worked his way around the French lines of communication and forced them to withdraw quickly.

War and defeat

Samori's army was well equipped with modern firearms and a complex structure of permanent units. His army was divided into an infantry wing of (Mandinka for infantry, usually slaves) and a cavalry wing sofa. By 1887, Samori could field 30,000 to 35,000 infantry and about 3,000 cavalry, in regular squadrons of 50 each. But, the French did not want to give him time to consolidate his position. Exploiting the rebellions of several of Ture's subject tribes, who were animist and resisted Islam, the French continued to expand into his westernmost holdings. They forced Ture to sign several treaties ceding territory to them between 1886 and 1889.

Between 1889 and 1894, Ture's army ravaged Wassoulou and expelled or enslaved most of the population.[4]

In March 1891, a French force under Colonel Louis Archinard launched a direct attack on Kankan. Knowing his fortifications could not stop French artillery, Ture began a war of manoeuvre. Despite victories against isolated French columns (for example at Dabadugu in September 1891), Ture failed to push the French from the core of his kingdom. In June 1892, Archinard's replacement, Colonel Humbert, leading a small, well-supplied force of picked men, captured Ture's capital of Bissandugu. In another blow, the British had stopped selling breech loaders to Ture in accordance with the Brussels Convention of 1890.

Ture shifted his base of operations eastward, toward the Bandama and Comoe River in Dabakala. He instituted a scorched earth policy, devastating each area before he evacuated it. Though this manoeuvre cut Ture off from Sierra Leone and Liberia, his last sources of modern weapons, it also delayed French pursuit.[5] After the spring of 1893, the French partially succeeded in cutting off Ture's sources of weapons which was supplied by the British traders since the late 1880s. Ture tried to negotiate with the British in their colonial domains in Ghana to work against the French interest, but the British would not intervene directly against France.[6]

He tried to build an anti-colonial alliance with Ashanti Empire but failed when Ashante was defeated by the British and fighting between Ture and British soldiers in 1897. The fall of other anti-colonial armies, particularly Babemba Traoré at Sikasso, permitted the French colonial army to launch a concentrated assault against Ture. By 1898, he lost almost all of his territory and fled into the mountains of western Ivory Coast. He was captured on 29 September 1898 by the French captain Henri Gouraud and was exiled to Gabon despite his request to return to southern Guinea.

Ture died in captivity on an island in the Ogooué River, near Ndjolé on June 2, 1900, following a bout of pneumonia. His tomb is at the Camayanne Mausoleum, within the gardens of Conakry Grand Mosque.

Legacy

- He is considered a powerful example of resistance to French colonial forces and known for his building collaboration among diverse groups, as well as his war strategies.

- His great-grandson, Ahmed Sékou Touré, was elected as the first President of Guinea after it became independent.

In popular culture

- Massa Makan Diabaté's play Une hyène à jeun (A Hyena with an Empty Stomach, 1988) dramatizes Samori Ture's signing of the 1886 Treaty of Kéniéba-Koura, which granted the left bank of the Niger to France.

- Guinean band Bembeya Jazz National commemorated Ture in their 1969 release Regard sur le passé. The album draws upon Manding Djeli traditions and consists of two epic recordings that recount Ture's anti-colonial resistance and nation-building.

- Author Ta-Nehisi Coates references Ture in his book Between the World and Me when explaining to his son where his name Samori came from.

- Ivorien reggae superstar Alpha Blondy eulogises Ture in his hit song "Bory Samory" from the Album Cocody Rock.

Footnotes

- Maddy, Monique. Learning to Love Africa, p. 156.

- Vandervort, Bruce, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830-1914, p. 128.

- Asanti states that the arms were "imported from the free country of Sierra Leone or made by his own Mandinka blacksmiths." Asanti, p. 234.

- Klein, Martin, Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa (Cambridge, 1998), 109–11.

- Asanti, p. 235.

- Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. 2 February 2012. p. 55. ISBN 9780195382075.

References

- Ajayi, J.F. Ade, ed. (1989). UNESCO General History of Africa. Vol. VI: Africa in the Nineteenth Century until the 1880s. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-92-3-101712-4.

- Asante, Molefi Kete, The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony (New York: Routledge, 2007).

- Boahen, A. Adu, ed. UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. VII: Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880-1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

- Gann, L. H., and Peter Duigan, eds. Colonialism in Africa, 1870–1960, Vol. 1: The History and Politics of Colonialism 1870-1914 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

- Oliver, Roland, and G. N. Sanderson, eds. The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 6: from 1870-1905 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Sources

- Boahen, A. Adu (1989). African Perspective on Colonialism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 144 pages. ISBN 0-8018-3931-9.

- Boahen, A. Adu (1990). Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880-1935. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 357 pages. ISBN 0-520-06702-9.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. California: University of California Press. p. 1076 pages. ISBN 0-520-03916-5.

- Person, Yves (1968–1975). Samori, Une révolution Dyula. 3 volumes. Dakar: IFAN. p. 2377 pages. A fourth volume of maps published in Paris in 1990. Monumental work of history perhaps unique in African literature.

- Piłaszewicz, Stanisław. 1991. On the Veracity of Oral Tradition as a Historical Source: - the Case of Samori Ture. In Unwritten Testimonies of the African Past. Proceedings of the International Symposium held in Ojrzanów n. Warsaw on 07-08 November 1989 ed. by S. Piłaszewicz and E. Rzewuski, (Orientalia Varsoviensia 2). Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.