Usman dan Fodio

Shaihu Usman dan Fodio, born Usuman ɓin Foduye, (also referred to as Arabic: عثمان بن فودي, Shaikh Usman Ibn Fodio, Shehu Uthman Dan Fuduye, Shehu Usman dan Fodio or Shaikh Uthman Ibn Fodio) (born 15 December 1754, Gobir – died 20 April 1817, Sokoto)[5] was a Fulani religious teacher, revolutionary, military leader, writer, and promoter of Sunni Islam and the founder of the Sokoto Caliphate.[6]

| Usman bin Fodio عثمان بن فودي | |

|---|---|

| Sultan of Sokoto, Amir al-Mu'minin, Imama | |

| Reign | 1803–1815 |

| Coronation | Gudu, June 1803 |

| Successor | Eastern areas (Sokoto): Muhammed Bello, son. Western areas (Gwandu): Abdullahi dan Fodio, brother. |

| Born | 15 December 1754 Gobir |

| Died | 20 April 1817 Sokoto |

| Burial | Hubare, Sokoto.[1] |

| Wives |

|

| Issue | 23 children, including: Muhammed Bello Nana Asmau Abu Bakr Atiku |

| Dynasty | Sokoto Caliphate |

| Father | Mallam Muhammadu Fodio |

| Mother | Maimuna |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Maliki |

| Creed | Ash'ari[2] |

| Tariqa | Qadiri[3][4] |

Dan Fodio was one of a class of urbanized ethnic Fula people living in the Hausa Kingdoms since the early 1400s[7] in what is now northern Nigeria. He belonged to the Maliki school of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) and the Qadiri branch of Sufism.[8]

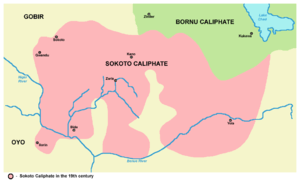

Dan Fodio taught Maliki fiqh in the city-state of Gobir until 1802 when, motivated by his reformist ideas and suffering increasing repression by local authorities, he led his followers into exile[9]. This exile began a political and social revolution which spread from Gobir throughout modern Nigeria and Cameroon, and was echoed in a jihad movement led by the Fulapeople across West Africa. Dan Fodio declined much of the pomp of rulership, and while developing contacts with religious reformists and jihad leaders across Africa, he soon passed actual leadership of the Sokoto state to his son, Muhammed Bello[10].

Dan Fodio wrote more than a hundred books concerning religion, government, culture, and society. He developed a critique of existing African Muslim elites for what he saw as their greed, paganism, violation of the standards of Sharia law, and use of heavy taxation. He encouraged literacy and scholarship, for women as well as men, and several of his daughters emerged as scholars and writers[11]. His writings and sayings continue to be much quoted today, and are often affectionately referred to as Shehu in Nigeria. Some followers consider dan Fodio to have been a mujaddid, a divinely inspired "reformer of Islam".[12]

Dan Fodio's uprising was a major episode of a movement described as the Fula jihads in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.[13] It followed the jihads successfully waged in Futa Bundu, Futa Tooro, and Fouta Djallon between 1650 and 1750, which led to the creation of those three Islamic states. In his turn, the Shehu inspired a number of later West African jihads, including those of Seku Amadu, founder of the Massina Empire, Omar Saidou Tall, founder of the Toucouleur Empire, who married one of dan Fodio's granddaughters, and Modibo Adama, founder of the Adamawa Emirate.

Early life and training

Dan Fodio was a Fulani descendant of a Torodbe family that was well established in Hausaland.[14][15] He was well educated in classical Islamic science, philosophy, and theology. He also became a revered religious thinker. His teacher, Jibril ibn ʻUmar, argued that it was the duty and within the power of religious movements to establish an ideal society free from oppression and vice. Jibril was a North African ʻalim who gave his apprentice a broader perspective of Muslim reformist ideas in other parts of the Muslim world. Jibril b. ʻUmar was known as an uncompromising opponent of corrupt practices and a stuanch proponent of Jihad. He began his itinerant preaching as a mallam in 1774-1775. Inspired by Jibril b. Umar, Uthman Dan Fodio criticized the Hausa Kingdoms for their unjust and illegal taxes, confiscations of property, compulsory military service, bribery, gift taking and the enslavement of other Muslims. Dan Fodio also criticized the Hausa rulers for condoning paganism, worshipping fetishes, and believing in the power of talismans, divination, and conjuring. He also insisted on the observance of Maliki fiqh in the commercial, criminal, and personal sectors. Usman also denounced the mixing of men and women, pagan customs, dancing at bridal feasts, and inheritance practices contrary to Sharia[16].

Uthman was also very influenced by the mushahada or mystical visions he was having. In 1789 a vision led him to believe he had the power to work miracles, and to teach his own mystical wird, or litany. His litanies are still widely practiced and distributed in the Islamic world.[17] Dan Fodio later had visions of Abdul Qadir Gilani, the founder of the Qadiri tariqah, an ascension to heaven, where he was initiated into the Qadiriyya and the spiritual lineage of the Prophet. His theological writings dealt with concepts of the mujaddid "renewer" and the role of the Ulama in teaching history, and other works in Arabic and the Fula language.[15]

Dan Fodio broke from the royal court and used his influence to secure approval for creating a religious community in his hometown of Degel that would, Dan Fodio hoped, be a model town. He stayed there for twenty years, writing, teaching, and preaching. As in other Islamic societies, the autonomy of Muslim communities under ulama leadership made it possible to resist the state and the state version of Islam in the name of sharia and the ideal caliphate.[15]

The Fulani War

Uthman Dan Fodio's appeal to justice and morality rallied the outcasts of Hausa society. He found his followers among the Fulbe and Fulani. The Fulbe and Fulani were primarily cattle pastoralists. These pastoralist communities were led by the clerics living in rural communities who were Fulfude speakers and closely connected to the pastoralists. The Fulani would later hold the most important offices of the new states. Hausa peasants, runaway slaves, itinerant preachers, and others also responded to Uthman's preaching. His jihad served to integrate a number of peoples into a single religio-political movement.[18]

In 1802, Yunfa, the ruler of Gobir and one of dan Fodio's students, turned against him, revoking Degel's autonomy and attempting to assassinate dan Fodio[19]. Dan Fodio and his followers declared hijrah and fled into the western grasslands of Gudu, where they turned for help to the local Fulani nomads. Uthman's followers at this time entitled him Amir al-Mu'minin and sarkin muslim - head of the Muslim community[20]. The rulers of Gobir forbade Muslims to wear turbans and veils, prohibited conversions, and ordered converts to Islam to return to their old religion.[18] In his book Tanbih al-ikhwan 'ala ahwal al-Sudan (“Concerning the Government of Our Country and Neighboring Countries in the Sudan”) Usman wrote: "The government of a country is the government of its king without question. If the king is a Muslim, his land is Muslim; if he is an unbeliever, his land is a land of unbelievers. In these circumstances it is obligatory for anyone to leave it for another country".[21] Usman did exactly this when he left Gobir in 1802. Yunfa then turned for aid to the other leaders of the Hausa states, warning them that dan Fodio could trigger a widespread jihad.[22]

Usman dan Fodio was proclaimed Amir al-Muminin or Commander of the Faithful in Gudu. This made him a political as well as religious leader, giving him the authority to declare and pursue a jihad, raise an army and become its commander. A widespread uprising began in Hausaland. This uprising was largely composed of the Fulani, who held a powerful military advantage with their cavalry. It was also widely supported by the Hausa peasantry, who felt over-taxed and oppressed by their rulers[23]. Usuman started the jihad against Gobir in 1804[24].

At the time of the war Fulani communications were carried along trade routes and rivers draining into the Niger-Benue valley, as well as the delta and the lagoons. The call for jihad reached not only other Hausa states such as Kano, Daura, Katsina, and Zaria, but also Borno, Gombe, Adamawa, Nupe[25]. These were all places with major or minor groups of Fulani alims.

By 1808 Uthman had defeated the rulers of Gobir, Kano, Katsina, and other Hausa Kingdoms[26]. Usman Dan Fodio was defeated by Ibadan warlords in Yorubaland as far as the forest zone.[18] After only a few years of the Fulani War, Dan Fodio found himself in command of the hausa state, the Fulani Empire. His son Muhammed Bello and his brother Abdullahi carried on the jihad and took care of the administration[27]. Dan Fodio worked to establish an efficient government grounded in Islamic law. After 1811, Usman retired and continued writing about the righteous conduct of the Muslim religion. After his death in 1817, his son, Muhammed Bello, succeeded his as amir al-mu’minin and became the ruler of the Sokoto Caliphate, which was the biggest state south of the Sahara at that time. Usman’s brother Abdullahi was given the title Emir of Gwandu and was placed in charge of the Western Emirates, Nupe. Thus all Hausa states, parts of Nupe and Fulani outposts in Bauchi and Adamawa were all ruled by a single politico-religious system. By 1830 the jihad had engulfed most of what are now northern Nigeria and the northern Cameroons. From the time of Usman dan Fodio to the British conquest at the beginning of the twentieth century there were twelve caliphs.

The Sokoto Caliphate was a combination of an Islamic state and a modified Hausa monarchy. Muhammed Bello introduced Islamic administration, Muslim judges, market inspectors, and prayer leaders were appointed, and an Islamic tax and land system was instituted with revenues on the land considered kharaj and the fees levied on individual subjects called jizya, as in classical Islamic times. The Fulani cattle-herding nomads were sedentarized and converted to sheep and goat raising as part of an effort to bring them under the rule of Muslim law. Mosques and Madrassahs were built to teach the populace Islam. The state patronized large numbers of religious scholars or mallams. Sufism became widespread. Arabic, Hausa, and Fulfulde languages saw a revival of poetry and Islam was taught in Hausa and Fulfide.[18]

Religious and political impact

Many of the Fulani led by Usman dan Fodio were unhappy that the rulers of the Hausa states were mingling Islam with aspects of the traditional regional religion. Usman created a theocratic state with a stricter interpretation of Islam. In Tanbih al-ikhwan 'ala ahwal al-Sudan, he wrote: "As for the sultans, they are undoubtedly unbelievers, even though they may profess the religion of Islam, because they practice polytheistic rituals and turn people away from the path of God and raise the flag of a worldly kingdom above the banner of Islam. All this is unbelief according to the consensus of opinions".[28]

In Islam outside the Arab World, David Westerlund wrote: "The jihad resulted in a federal theocratic state, with extensive autonomy for emirates, recognizing the spiritual authority of the caliph or the sultan of Sokoto".[29]

Usman addressed in his books what he saw as the flaws and demerits of the African non-Muslim or nominally Muslim rulers. Some of the accusations he made were corruption at various levels of the administration and neglect of the rights of ordinary people. Usman also criticized heavy taxation and obstruction of the business and trade of the Hausa states by the legal system.

Family

Usman dan Fodio was described as well past 6 feet, lean and looking very much like his mother Sayda Hauwa. His brother Abdullahi dan Fodio (1761-1829) was also over 6 feet in height and was described as looking more like their father Muhammad Fodio, with a darker skin hue and a portly physique later in his life.

In Rawd al-Janaan (The Meadows of Paradise), Waziri Gidado dan Laima (1777-1851) listed Dan Fodio's wives as:

His first cousin Maymuna with whom he had 11 children, including Aliyu (1770s-1790s) and the twins Hasan (1793- November 1817) and Nana Asma'u (1793-1864). Maymuna died sometime after the birth of her youngest children.

Aisha dan Muhammad Sa'd. She was also known as "Gaabdo" (Joy in Fulfulde) and as "Iyya Garka" (Hausa for Lady of the House/Compound). Iyya Garka was famed for her Islamic knowledge and for being the matriarch of the family. She outlived her husband by many decades. Among others, she was the mother of:

- Muhammad Sa'd (1777-before 1804). Eldest surviving son of Shehu dan Fodio, he was noted for his intellectual pursuits and his early death.

- Khadija (c.1778-1856). Preceptor to her sister Asma’u and Aisha al-Kammu, wife to her brother Muhammad Bello. She was married to the scholarly Mustafa (c.1770-1855), the chief secretary to Shaykh Usman dan Fodio. By him, she was the mother of the Sheikh Abdul Qadir dan Tafa (1803-1864), a Sufi, Islamic cleric and historian

- Muhammad Sambo (c.1780-1826). A Qadiri Sufi Scholar, Sambo was the first to pledge allegiance to his younger brother Bello when the latter became Caliph in 1817.

- Muhammad Buhari (1785-1840). Buhari was a scholar and a lieutenant to the Sultans of Sokoto. He was Sarkin of the ribat of Tambuwal, and was famous for his campaigns in Nupe along with the Emirs of Gwandu. Muhammad Buhari is the great-grandfather of Sultan Ibrahim Dasuki.

Hauwa, known also as "Inna Garka" (Mother of the House in Hausa) and Bikaraga. She was described as being prone to asceticism. Among her children were

- Muhammad Bello (1781-1837), the second Sultan of Sokoto. Author of a chronicle of the Fulani Jihad (Infaq al-Maysur) and a notable scholar.

- Abu Bakr Atiku (1783-1842), the third Sultan of Sokoto. Atiku was known for having inherited many of his father's esoteric secrets. He ruled between 1837 and 1842 and died following the failed siege of Tsibiri

- Fatima (1787-1838), also known as "Mo 'Inna" (Inna's child, to distinguish her from another Fatima). She was married to Sarkin Yaki Aliyu Jedo, generalissimo of the Sokoto armies.

Hajjo, by whom he was the father of Abdul Qadir (1807-1836) who was known as one of the best poets of Sokoto. Abdul Qadir died from battle wounds during Sultan Bello's last campaign, in Zamfara. He was buried at Baraya Zaki.

Shatura, by whom he was the father of Ahmadu Rufai (1812-1873). Rufai was Sarkin of Silame and later became Sultan of Sokoto (1867-1873).

By his unique concubine Mariyatu, Sheykh Dan Fodio was father to:

- Amina

- Ibrahim Dasuki

- Hajara

- Uwar Deji Mariyam (c.1808- fl. 1880s). Mariyam dan Shehu was a scholar like her sister Khadija, Fatima and Asma'u. Following the latter's death, she led the Yan Taru movement which promoted women's education. She was first married to Muhammad Adde dan Waziri Gidado, with whom she had two daughters. Following the latter's early death, she married the Emir of Kano Ibrahim Dabo (r. 1819-1846). She had no children in her second union. Mariyam wielded much influence following her return to Sokoto in the later 1840s. She was an influential counselor to her nephews who became Sultans, and often served as liaison in their dealings with Kano. In the 1880s during the rule of Sultan Umar dan Ali dan Bello (r. 1881-1892), she penned a letter to her stepson Emir Muhammad Bello (r. 1883-1893) of Kano, rebuking the pretensions of her grand-nephew Hayatu dan Sai'd dan Sultan Bello (1840-1898), who was promoting mass emigration to Adamawa, as "amil" of the Sudanese Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad.

- Mallam 'Isa (1817-c.1870), who was Shaykh Dan Fodio's youngest and posthumous child. Along with Asma'u, he translated in Hausa and Arabic, many of his father's works that were written in Fulfulde. Mallam 'Isa was also named Sarkin Yamma by his brother Sultan Bello. He died sometime during the rule of Sultan Rufa'i (1867-1873).

Writings

Usman dan Fodio "wrote hundreds of works on Islamic sciences ranging from creed, Maliki jurisprudence, hadith criticism, poetry and Islamic spirituality", the majority of them being in Arabic.[30] He also penned about 480 poems in Arabic, Fulfulde, and Hausa.[31]

Further reading

- Writings of Usman dan Fodio, in The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Fourth Edition/ Volume II: Since 1500, ISBN 978-12858702-43 (page:233-236)

- Asma'u, Nana. Collected Works of Nana Asma'u. Jean Boyd and Beverly B. Mack, eds. East Lansing, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

- Omipidan Teslim Usman Dan Fodio (1754-1817) OldNaija

- Mervyn Hiskett. The Sword of Truth: The Life and Times of the Shehu Usuman Dan Fodio. Northwestern Univ Pr; 1973, Reprint edition (March 1994). ISBN 0-8101-1115-2

- Ibraheem Sulaiman. The Islamic State and the Challenge of History: Ideals, Policies, and Operation of the Sokoto Caliphate. Mansell (1987). ISBN 0-7201-1857-3

- Ibraheem Sulaiman. A Revolution in History: The Jihad of Usman dan Fodio.

- Isam Ghanem. The Causes and Motives of the Jihad in Northern Nigeria. in Man, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 4 (Dec., 1975), pp. 623–624

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. The Tradition of Tajdeed in West Africa: An Overview[32] International Seminar on Intellectual Tradition in the Sokoto Caliphate & Borno. Center for Islamic Studies, University of Sokoto (June 1987)

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. The Contents, Methods and Impact of Shehu Usman Dan Fodio's Teachings (1774-1804)[33]

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. The Jihad of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio and its Impact Beyond the Sokoto Caliphate.[34] A Paper read at a Symposium in Honour of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio at International University of Africa, Khartoum, Sudan, from 19 to 21 November 1995.

- Usman Muhammad Bugaje. Shaykh Uthman Ibn Fodio and the Revival of Islam in Hausaland,[35] (1996).

- Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Nigeria: A Country Study.[36] Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991.

- B. G. Martin. Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. 1978.

- Jean Boyd. The Caliph's Sister, Nana Asma'u, 1793–1865: Teacher, Poet and Islamic Leader.

- Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014. pg 469-472

- Nikki R. Keddie. The Revolt of Islam, 1700 to 1993: Comparative Considerations & Relations to Imperialism. in Comparative Studies in Society & History, Vol. 36, No. 3 (Jul., 1994), pp. 463–487

- R. A. Adeleye. Power and Diplomacy in Northern Nigeria 1804–1906. 1972.

- Hugh A.S. Johnston . Fulani Empire of Sokoto. Oxford: 1967. ISBN 0-19-215428-1.

- S. J. Hogben and A. H. M. Kirk-Greene, The Emirates of Northern Nigeria, Oxford: 1966.

- J. S. Trimgham, Islam in West Africa, Oxford, 1959.

- 'Umar al-Nagar. The Asanid of Shehu Dan Fodio: How Far are they a Contribution to his Biography?, Sudanic Africa, Volume 13, 2002 (pp. 101–110).

- Paul E. Lovejoy. Transformations in Slavery - A History of Slavery in Africa. No 36 in the African Studies series, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-78430-1

- Paul E. Lovejoy. Fugitive Slaves: Resistance to Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate, In Resistance: Studies in African, Caribbean, & Afro-American History. University of Massachusetts. (1986).

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Mariza C. Soares (Eds). Muslim Encounters With Slavery in Brazil. Markus Wiener Pub ( 2007) ISBN 1-55876-378-3

- F. H. El-Masri, "The life of Uthman b. Foduye before the Jihad", Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria (1963), pp. 435–48.

- M. A. Al-Hajj, "The Writings of Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio", Kano Studies, Nigeria (1), 2(1974/77).

- David Robinson. "Revolutions in the Western Sudan," in Levtzion, Nehemia and Randall L. Pouwels (eds). The History of Islam in Africa. Oxford: James Currey Ltd, 2000.

- Bunza[37]

See also

References

- OnlineNigeria.com. SOKOTO STATE, Background Information (2/10/2003).

- Jackson, Sherman A. (2009). Islam and the Problem of Black Suffering. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0195382064.

- University of Pennsylvania African Studies Center: "An Interview on Uthman dan Fodio" by Shireen Ahmed 22 June 1995

- Loimeier, Roman (2011). Islamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria. Northwestern University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0810128101.

- Hunwick, John O. 1995. "Arabic Literature in Africa: the Writings of Central Sudanic Africa (pp.

- I. Suleiman, The African Caliphate: The Life, Works and Teachings of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio (1757-1817) (2009).

- T. A. Osae & S. N. Nwabara (1968). a Short history of WEST AFRICA A.D 1000-1800. Great Britain: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 80. ISBN 0 340 07771 9.

- The Muslim 500: "Amirul Mu’minin Sheikh as Sultan Muhammadu Sa’adu Abubakar III" retrieved 15 May 2014

- "UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI CENTRE FOR DISTANCE LEARNING - PDF Free Download". religiondocbox.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Usman Dan Fodio's Biography". Fulbe History and Heritage. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- guardian.ng https://guardian.ng/sunday-magazine/usman-dan-fodio-a-great-reformer/. Retrieved 25 May 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - John O. Hunwick. African And Islamic Revival in Sudanic Africa: A Journal of Historical Sources : #6 (1995).

- "Suret-Canale, Jean. "The Social and Historical Significance of the Fulɓe Hegemonies in the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries." In Essays on African History: From the Slave Trade to Neocolonialism. translated from the French by Christopher Hurst. C. Hurst & Co., London., pp. 25-55". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Britannica Encyclopedia: "Usman dan Fodio" retrieved 15 May 2014

- Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014. pg 469

- "Keywords; history, nation building, Nigeria, role | Government | Politics". Scribd. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- https://archive.org/details/DalailuShehu "Dalailu Shehu Usman Dan Fodio." Internet Archive. Accessed 27 May 2017.

- Lapidus, pg 470

- "Usman Dan Fodio: Progenitor Of The Sokoto Caliphate". The Republican News. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "THE EMPIRES AND DYNASTIES – The Muslim Yearbook". Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Usman dan Fodio: Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- The Islamic Slave Revolts of Bahia, Brazil: A Continuity of the 19th Century Jihaad Movements of Western Sudan?, by Abu Alfa Muhammed Shareef bin Farid, Sankore' Institute of Islamic African Studies, www.sankore.org. Archived 15 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

Also see Lovejoy (2007), below, on this. - "Usman dan Fodio | Fulani leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Fodio, Usuman Dan | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Ososanya, Tunde (29 March 2018). "Usman Dan Fodio: History, legacy and why he declared jihad". Legit.ng - Nigeria news. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Usman dan Fodio: Founder of the Sokoto Caliphate | DW | 24.02.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Muḥammad Bello | Fulani emir of Sokoto". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- "Salaam Knowledge". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Christopher Steed and David Westerlund. Nigeria in David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg (eds). Islam Outside the Arab World. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. ISBN 0-312-22691-8

- Dawud Walid (15 February 2017), "Uthman Dan Fodio: One of the Shining Stars of West Africa", Al Madina Institute. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Yahaya, Ibrahim Yaro (1988). "The Development of Hausa Literature. in Yemi Ogunbiyi, ed. Perspectives on Nigerian Literature: 1700 to the Present. Lagos: Guardian Books" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011. Obafemi, Olu. 2010. "50 Years of Nigerian Literature: Prospects and Problems" Keynote Address presented at the Garden City Literary Festival, at Port Harcourt, Nigeria, 8-9 Dec 2010]

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Nigeria Usman Dan Fodio and the Sokoto Caliphate". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Adam, Abba Idris., "Re-inventing Islamic Civilization in the Sudanic Belt: The Role of Sheikh Usman Dan Fodio." Journal of Modern Education Review 4.6 (2014): 457–465. online

- Suleiman, I. The African Caliphate: The Life, Works and Teachings of Shaykh Usman Dan Fodio (1757-1817) (2009).