Imam

Imam (/ɪˈmɑːm/; Arabic: إمام imām; plural: أئمة aʼimmah) is an Islamic leadership position.

It is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque and Muslim community among Sunni Muslims. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, serve as community leaders , and provide religious guidance. In Yemen, the title was formerly given to the king of the country.

For Shi'a Muslims, the Imams are leaders of the Islamic community or ummah after the Prophet. The term is only applicable to the members of Ahl al-Bayt, the family of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, designated as infallibles.[1]

Sunni imams

The Sunni branch of Islam does not have imams in the same sense as the Shi'a, an important distinction often overlooked by those outside of the Islamic religion. In everyday terms, the imam for Sunni Muslims is the one who leads Islamic formal (Fard) prayers, even in locations besides the mosque, whenever prayers are done in a group of two or more with one person leading (imam) and the others following by copying his ritual actions of worship. Friday sermon is most often given by an appointed imam. All mosques have an imam to lead the (congregational) prayers, even though it may sometimes just be a member from the gathered congregation rather than an officially appointed salaried person. The position of women as imams is controversial. The person that should be chosen, according to Hadith, is one who has most knowledge of the Quran and Sunnah (prophetic tradition) and is of good character.

The term is also used for a recognized religious scholar or authority in Islam, often for the founding scholars of the four Sunni madhhabs, or schools of jurisprudence (fiqh). It may also refer to the Muslim scholars who created the analytical sciences related to Hadith or it may refer to the heads of Muhammad's family in their generational times.[2]

The Position of Imams In Turkey

Imams are appointed by the state to work at mosques and they are required to be graduates of an İmam Hatip high school or have a university degree in Theology. This is an official position regulated by the Presidency of Religious Affairs[3] in Turkey and only males are appointed to this position while female officials under the same state organisation work as preachers and Qur'an course tutors, religious services experts. These officials are supposed to belong to the Hanafi school of the Sunni sect.

A central figure in an Islamic movement is also called as an Imam like the Imam Nabhawi in Syria and Ahmad Raza Khan in India and Pakistan is also called as the Imam for Sunni Muslims.

Shi'a imams

In the Shi'a context, an imam is not only presented as the man of God par excellence, but as participating fully in the names, attributes, and acts that theology usually reserves for God alone.[4] Imams have a meaning more central to belief, referring to leaders of the community. Twelver and Ismaili Shi'a believe that these imams are chosen by God to be perfect examples for the faithful and to lead all humanity in all aspects of life. They also believe that all the imams chosen are free from committing any sin, impeccability which is called ismah. These leaders must be followed since they are appointed by God.

Twelver

Here follows a list of the Twelvers Shia imams:

| Number | Name (Full/Kunya) | Title (Arabic/Turkish)[5] | Birth–Death (CE/AH)[6] | Importance | Birthplace (present day country) | Place of death and burial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ali ibn Abu Talib علي بن أبي طالب Abu al-Hassan or Abu al-Husayn أبو الحسین or أبو الحسن |

Amir al-Mu'minin (Commander of the Faithful)[7] Birinci Ali[8] |

600–661[7] 23 BH–40[9] |

The first imam and successor of Muhammad in Shia Islam; however, the Sunnis acknowledge him as the fourth Caliph as well. He holds a high position in almost all Sufi Muslim orders (Turuq); the members of these orders trace their lineage to Muhammad through him.[7] | Mecca, Saudi Arabia[7] | Assassinated by Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam, a Kharijite in Kufa, who slashed him with a poisoned sword.[7][10] Buried at the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf, Iraq. |

| 2 | Hassan ibn Ali الحسن بن علي Abu Muhammad أبو محمد |

al-Mujtaba İkinci Ali[8] |

624–670[11]

3–50[12] |

He was the eldest surviving grandson of Muhammad through Muhammad's daughter, Fatimah Zahra. Hasan succeeded his father as the caliph in Kufa, and on the basis of peace treaty with Muawiya I, he relinquished control of Iraq following a reign of seven months.[13] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[11] | Poisoned by his wife in Medina, Saudi Arabia.[14] Buried in Jannat al-Baqi. |

| 3 | Husayn ibn Ali الحسین بن علي Abu Abdillah أبو عبدالله |

Sayed al-Shuhada Üçüncü Ali[8] |

626–680[15]

4–61[16] |

He was a grandson of Muhammad. Husayn opposed the validity of Caliph Yazid I. As a result, he and his family were later killed in the Battle of Karbala by Yazid's forces. After this incident, the commemoration of Husayn ibn Ali has become a central ritual in Shia identity.[15][17] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[15] | Killed on Day of Ashura (10 Muharram) and beheaded at the Battle of Karbala.[15] Buried at the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, Iraq. |

| 4 | Ali ibn al-Hussein علي بن الحسین Abu Muhammad أبو محمد |

al-Sajjad, Zain al-Abedin[18]

Dördüncü Ali[8] |

658-9[18] – 712[19]

38[18]–95[19] |

Author of prayers in Sahifa al-Sajjadiyya, which is known as "The Psalm of the Household of the Prophet."[19] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[18] | According to most Shia scholars, he was poisoned on the order of Caliph al-Walid I in Medina, Saudi Arabia.[19] Buried in Jannat al-Baqi. |

| 5 | Muhammad ibn Ali محمد بن علي Abu Ja'far أبو جعفر |

al-Baqir al-Ulum (splitting open knowledge)[20] Beşinci Ali[8] |

677–732[20]

57–114[20] |

Sunni and Shia sources both describe him as one of the early and most eminent legal scholars, teaching many students during his tenure.[20][21] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[20] | According to some Shia scholars, he was poisoned by Ibrahim ibn Walid ibn 'Abdallah in Medina, Saudi Arabia on the order of Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik.[19] Buried in Jannat al-Baqi. |

| 6 | Ja'far ibn Muhammad جعفر بن محمد Abu Abdillah أبو عبدالله |

al-Sadiq[22]

Altıncı Ali[8] |

702–765[22]

83–148[22] |

Established the Ja'fari jurisprudence and developed the Theology of Shia. He instructed many scholars in different fields, including Abu Hanifah and Malik ibn Anas in fiqh, Wasil ibn Ata and Hisham ibn Hakam in Islamic theology, and Jābir ibn Hayyān in science and alchemy.[23] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[22] | According to Shia sources, he was poisoned in Medina, Saudi Arabia on the order of Caliph Al-Mansur.[22] Buried in Jannat al-Baqi. |

| 7 | Musa ibn Ja'far موسی بن جعفر Abu al-Hassan I أبو الحسن الأول[24] |

al-Kazim[25]

Yedinci Ali[8] |

744–799[25]

128–183[25] |

Leader of the Shia community during the schism of Ismaili and other branches after the death of the former imam, Jafar al-Sadiq.[26] He established the network of agents who collected khums in the Shia community of the Middle East and the Greater Khorasan.[27] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[25] | Imprisoned and poisoned in Baghdad, Iraq on the order of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Buried in the Kazimayn shrine in Baghdad.[25] |

| 8 | Ali ibn Musa علي بن موسی [24] |

al-Rida, Reza[28]

Sekizinci Ali[8] |

765–817[28]

148–203[28] |

Made crown-prince by Caliph Al-Ma'mun, and famous for his discussions with both Muslim and non-Muslim religious scholars.[28] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[28] | According to Shia sources, he was poisoned in Mashad, Iran on the order of Caliph Al-Ma'mun. Buried in the Imam Reza shrine in Mashad.[28] |

| 9 | Muhammad ibn Ali محمد بن علي Abu Ja'far أبو جعفر |

al-Taqi, al-Jawad[29]

Dokuzuncu Ali[8] |

810–835[29]

195–220[29] |

Famous for his generosity and piety in the face of persecution by the Abbasid caliphate. | Medina, Saudi Arabia[29] | Poisoned by his wife, Al-Ma'mun's daughter, in Baghdad, Iraq on the order of Caliph Al-Mu'tasim. Buried in the Kazmain shrine in Baghdad.[29] |

| 10 | Ali ibn Muhammad علي بن محمد Abu al-Hassan III أبو الحسن الثالث[30] |

al-Hadi, al-Naqi[30]

Onuncu Ali[8] |

827–868[30]

212–254[30] |

Strengthened the network of deputies in the Shia community. He sent them instructions, and received in turn financial contributions of the faithful from the khums and religious vows.[30] | Surayya, a village near Medina, Saudi Arabia[30] | According to Shia sources, he was poisoned in Samarra, Iraq on the order of Caliph Al-Mu'tazz.[31] Buried in the Al Askari Mosque in Samarra. |

| 11 | Hassan ibn Ali الحسن بن علي Abu Muhammad أبو محمد |

al-Askari[32]

Onbirinci Ali[8] |

846–874[32]

232–260[32] |

For most of his life, the Abbasid Caliph, Al-Mu'tamid, placed restrictions on him after the death of his father. Repression of the Shi'ite population was particularly high at the time due to their large size and growing power.[33] | Medina, Saudi Arabia[32] | According to Shia, he was poisoned on the order of Caliph Al-Mu'tamid in Samarra, Iraq. Buried in Al Askari Mosque in Samarra.[34] |

| 12 | Muhammad ibn al-Hassan محمد بن الحسن Abu al-Qasim أبو القاسم |

al-Mahdi, Hidden Imam, al-Hujjah[35]

Onikinci Ali[8] |

868–unknown[36]

255–unknown[36] |

According to Twelver doctrine, he is the current imam and the promised Mahdi, a messianic figure who will return with Jesus. He will reestablish the rightful governance of Islam and replete the earth with justice and peace.[37] | Samarra, Iraq[36] | According to Shia doctrine, he has been living in the Occultation since 872, and will continue as long as God wills it.[36] |

Fatimah, also Fatimah al-Zahraa, daughter of Muhammed (615–632), is also considered infallible but not an Imam. The Shi'a believe that the last Imam, the 12th Imam Mahdi will one day emerge on the Day of Resurrection (Qiyamah).

Ismaili

See Imamah (Ismaili doctrine) and List of Ismaili imams for Ismaili imams.

Zaidi

See details under Zaidiyyah, Islamic history of Yemen and Imams of Yemen.

Imams as secular rulers

At times, imams have held both secular and religious authority. This was the case in Oman among the Kharijite or Ibadi sects. At times, the imams were elected. At other times the position was inherited, as with the Yaruba dynasty from 1624 and 1742. See List of rulers of Oman, the Rustamid dynasty: 776–909, Nabhani dynasty: 1154–1624, the Yaruba dynasty: 1624–1742, the Al Said: 1744–present for further information.[38] The Imamate of Futa Jallon (1727-1896) was a Fulani state in West Africa where secular power alternated between two lines of hereditary Imams, or almami.[39] In the Zaidi Shiite sect, imams were secular as well as spiritual leaders who held power in Yemen for more than a thousand years. In 897, a Zaidi ruler, al-Hadi ila'l-Haqq Yahya, founded a line of such imams, a theocratic form of government which survived until the second half of the 20th century. (See details under Zaidiyyah, History of Yemen, Imams of Yemen.)

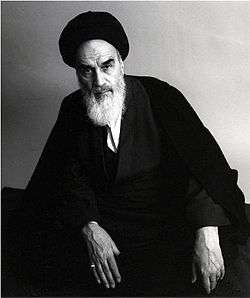

Ruhollah Khomeini is officially referred to as Imam in Iran. Several Iranian places and institutions are named "Imam Khomeini", including a city, an international airport, a hospital, and a university.

Gallery

Imams

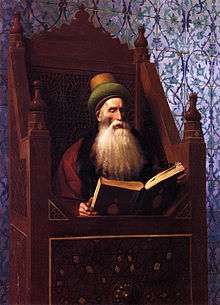

Discourse between Islamic Imams in the Mughal Empire.

Discourse between Islamic Imams in the Mughal Empire. Crimean Tatar imams teach the Quran. Lithograph by Carlo Bossoli.

Crimean Tatar imams teach the Quran. Lithograph by Carlo Bossoli. Imam presiding over prayer, North Africa

Imam presiding over prayer, North Africa Imam Shamil, Caucasus

Imam Shamil, Caucasus.jpg) Imam in Bosnia, c. 1906

Imam in Bosnia, c. 1906 Imam Khomeini, leader of the Iranian revolution.

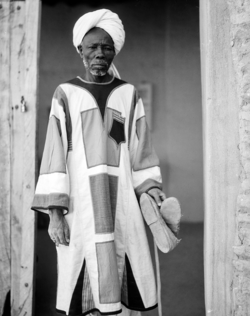

Imam Khomeini, leader of the Iranian revolution. An Imam in Omdurman, Sudan.

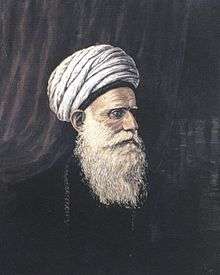

An Imam in Omdurman, Sudan.-begging_dervis.png) An Ottoman imam in Constantinople.

An Ottoman imam in Constantinople. A Bosniak military imam in the Austro-Hungarian Army.

A Bosniak military imam in the Austro-Hungarian Army.- Imam Thierno Ibrahima Thiello

- A Georgian Muslim imam from Tbilisi.

Tuanku Imam Bonjol (of South East Asia)

Tuanku Imam Bonjol (of South East Asia)

Muftis

Grand Mufti Mirza Huseyn Qayibzade of Tbilisi

Grand Mufti Mirza Huseyn Qayibzade of Tbilisi.f024.jpg) Travelling muftis of the Ottoman Empire

Travelling muftis of the Ottoman Empire Mufti, Jakub Szynkiewicz

Mufti, Jakub Szynkiewicz Grand Mufti Absattar Derbisali of Kazakhstan

Grand Mufti Absattar Derbisali of Kazakhstan Ottoman Grand Mufti

Ottoman Grand Mufti Ottoman Grand Mufti

Ottoman Grand Mufti.jpg) Tomb of mufti in Indonesia

Tomb of mufti in Indonesia Grand Mufti Talgat Tadzhuddin

Grand Mufti Talgat Tadzhuddin Mufti delivering a sermon

Mufti delivering a sermon Grand Mufti Ebrahim Desai

Grand Mufti Ebrahim Desai

Shaykh

Portrait of Shaykh ul-Islam by Ali bey Huseynzade

Portrait of Shaykh ul-Islam by Ali bey Huseynzade Shaykh Hamza Yusuf

Shaykh Hamza Yusuf Kurdish sheikhs, 1895.

Kurdish sheikhs, 1895. Sheykh of the Rufai Sufi Order

Sheykh of the Rufai Sufi Order

See also

Notes

- Corbin 1993, p. 30

- Dhami, Sangeeta; Sheikh, Aziz (November 2000). "The Muslim family". Western Journal of Medicine. 173 (5): 352–356. doi:10.1136/ewjm.173.5.352. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1071164. PMID 11069879.

- "Presidency of Religious Affairs". www.diyanet.gov.tr.

- Amir-Moezzi, Ali (2008). Spirituality and Islam. London: Tauris. p. 103. ISBN 9781845117382.

- The imam's Arabic titles are used by the majority of Twelver Shia who use Arabic as a liturgical language, including the Usooli, Akhbari, Shaykhi, and to a lesser extent Alawi. Turkish titles are generally used by Alevi, a fringe Twelver group, who make up around 10% of the world Shia population. The titles for each imam literally translate as "First Ali", "Second Ali", and so forth. Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Gale Group. 2004. ISBN 978-0-02-865769-1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - The abbreviation CE refers to the Common Era solar calendar, while AH refers to the Islamic Hijri lunar calendar.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. "Ali". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Gale Group. 2004. ISBN 978-0-02-865769-1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Tabatabae (1979), pp.190-192

- Tabatabae (1979), p.192

- "Hasan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979), pp.194–195

- Madelung, Wilferd. "Hasan ibn Ali". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Tabatabae (1979), p.195

- "al-Husayn". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979), pp.196–199

- Calmard, Jean. "Husayn ibn Ali". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Madelung, Wilferd. "'ALĪ B. AL-ḤOSAYN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979), p.202

- Madelung, Wilferd. "AL-BAQER, ABU JAFAR MOHAMMAD". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979), p.203

- Tabatabae (1979), p.203-204

- "Wāṣil ibn ʿAṭāʾ". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 1 January 2019.

- Madelung, Wilferd. "'ALĪ AL-HĀDĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- Tabatabae (1979), p.205

- Tabatabae (1979) p. 78

- Sachedina (1988), pp.53–54

- Tabatabae (1979), pp.205–207

- Tabatabae (1979), p. 207

- Madelung, Wilferd. "'ALĪ AL-HĀDĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979), pp.208–209

- Halm, H. "'ASKARĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979) pp. 209–210

- Tabatabae (1979), pp.209–210

- "Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Hujjah". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- Tabatabae (1979), pp.210–211

- Tabatabae (1979), pp. 211–214

- Miles, Samuel Barrett (1919). The Countries and Tribes of the Persian Gulf. Garnet Pub. pp. 50, 437. ISBN 978-1-873938-56-0. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- Holt, P. M.; Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Bernard Lewis (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

References

| Look up imam in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Imams. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Imam. |

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Encyclopædia Iranica. Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. ISBN 1-56859-050-4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Martin, Richard C. (2004). "Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World: A-L". Encyclopaedia of Islam and the Muslim world; vol.1. MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-865604-0.

- Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Gale Group. 2004. ISBN 978-0-02-865769-1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Corbin, Henry (1993) [1964]. History of Islamic Philosophy (in French). Translated by Sherrard, Liadain; Sherrard, Philip. London; Kegan Paul International in association with Islamic Publications for The Institute of Ismaili Studies. ISBN 0-7103-0416-1.

- Momen, Moojan (1985). TAn Introduction to Shi'i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelve. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03531-4.

- Sachedina, Abdulaziz Abdulhussein (1988). The Just Ruler (al-sultān Al-ʻādil) in Shīʻite Islam: The Comprehensive Authority of the Jurist in Imamite Jurisprudence. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-511915-0.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Translated by Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. SUNY press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.

- Corbin, Henry (1993). History of Islamic philosophy (Reprinted. ed.). London: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 9780710304162.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)