Kente cloth

Kente, known as nwentoma in Akan or Kete in Ewe, is an indigenous Ghanaian textile, made of interwoven cloth strips of silk and cotton.[1] Kente is made in Akan and Ewe lands, in Ghana, from the historic Ashanti Kingdom and Ewe Kingdom,[2] including the towns of Bonwire, Adanwomase, Sakora Wonoo, Agortime,Tsiame, Agbozume and Ntonso in the Kwabre areas of the Ashanti Region and Volta Region.[3] This fabric is worn by almost every Ghanaian tribe and represents national cultural identity.[1]

Kente comes from the word kenten, which means basket in the Asante dialect of Akan. Akans refer to kente as nwentoma, meaning woven cloth. It is an Akan royal and sacred cloth worn only in times of extreme importance and was the cloth of kings.[4] Over time, the use of kente became more widespread. In Agotime, kente weaving was not related to royalty, and weavers create kente for themselves or clients.[1] Its importance has remained and it is held in high esteem by southern Ghanaians. Globally, it is used in the design of academic stoles in graduation ceremonies.[5]

History

The history of the origin of the Kente weaving could go way back to ancient traditions of West African kingdoms from 300 A.D to 1600 A.D. Some historians claim the Kente is a development of a variety of weaving traditions which existed around the 17th century. Others too are of the view it originated from around the 11th century in West African weaving traditions. Excavations in some part of Africa has shown weaving instruments such as spindles whores and loom, weights in the early Moroe Empire.[6]

Characteristics

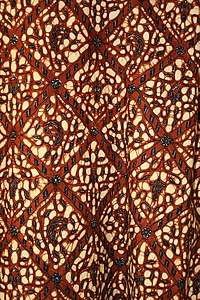

Kente cloth varies in complexity. Ahwepan refers to a simple design of warp stripes, created using plain weave and a single pair of heddles. The designs and motifs in kente cloth are traditionally abstract, but some weavers also include words, numbers and symbols in their work today.[5] In contrast, adweneasa, which translates as "my skill is exhausted", is a highly decorated type of kente with weft-based patterns woven into every available block of plain weave. Because of the intricate patterns, adweneasa cloth requires three heddles to weave.[7][8]

The Akan people choose kente cloths as much for their names as their colors and patterns. Although the cloths are identified primarily by the patterns found in the lengthwise (warp) threads, there is often little correlation between appearance and name. Names are derived from several sources, including proverbs, historical events, important chiefs, queen mothers, and plants. The cloth symbolizes high in value.

Bonwire, Sakora Wonoo, Ntonso, Safo and Adanwomase are noted for Kente weaving. However, other nearby towns are also into Kente weaving. Some of these towns and villages are Abira and Ahodwo.

All these towns are located in the Kwabre East Municipal in the Ashanti region.

Origins

West Africa has had a cloth weaving culture for centuries via the stripweave method, but Akan history tells of the cloth being created independent of outsider influence. Kente cloth has its origin from the Akan-Ashanti kingdoms in Ghana. The origin of kente is in the Akan empire of Bonoman. Most Akans migrated out of the area that was Bonoman to create various states.[9] The Ewe people of Ghana claim that they originated kente weaving (they don't claim inventing the art of weaving). They suggest that the name is derived from Kete which relates to the two alternating rhythmic actions (ke and te, meaning open and press in the Ewe language) associated with the weaving of the loom. But the main creators are the Bonwire people of Asanteman in the Ashanti Region of Ghana.[10]

Symbolic meanings of the colors

- black: maturation, intensified spiritual energy, spirits of ancestors, passing rites, mourning, and funerals

- blue: peacefulness, harmony, and love

- green: vegetation, planting, harvesting, growth, spiritual renewal

- gold: royalty, wealth, high status, glory, spiritual purity

- grey: healing and cleansing rituals; associated with ash

- maroon: the color of mother earth; associated with healing

- pink: assoc. with the female essence of life; a mild, gentle aspect of red

- purple: assoc. with feminine aspects of life; usually worn by women

- red: political and spiritual moods; bloodshed; sacrificial rites and death.

- silver: serenity, purity, joy; associated with the moon

- white: purification, sanctification rites and festive occasions

- yellow: preciousness, royalty, wealth, fertility, beauty

Traditions

A variety of kente patterns have been invented, each traditionally associated with a certain concept or set of concepts.[12] For example, the Obaakofoo Mmu Man pattern symbolizes democratic rule, Emaa Da symbolizes novel creativity and knowledge from experience, and Sika Fre Mogya symbolizes responsibility to share monetary success with one's relations.[13][10] Owu nhye da symbolizes hard work and living a morally constructive life.[10]

Legend has it that kente was first made by two Akan friends who went hunting in an Asanteman forest and found a spider making its web.[14] The friends stood and watched the spider for two days then returned home and implemented what they had seen.

Modern use of kente

Kente academic stoles are often used by African Americans as a symbol of ethnic pride.[15][16][17] This practice is also very popular with historically black Greek letter fraternities and sororities. African American students hold special ceremonies called "Donning of the Kente" where the stoles are presented to the graduates.[18]

Controversy

In June 2020, Democratic Party leaders in the United States caused controversy by wearing stoles made of Kente cloth to show support against systemic racism.[19] While it was claimed to be an act of unity with African-Americans, many, including Jade Bentil, a Ghanaian-Nigerian researcher, voiced objection and said that the white Democrats had no right to wear the Kente cloth stoles. On the other hand Congressional Black Caucus chair Karen Bass said, at a news conference for the introduction of the Justice in Policing Act of 2020, that the white lawmakers were showing solidarity, and April Reign, who is credited with initiating the #OscarsSoWhite hashtag,[20] while not a fan of the symbolism, suggested that the legislation's fate is more relevant than the event in the Capitol's Emancipation Hall.

References

- Anquandah, James; Kankpeyeng, Benjamin (2014). Current Perspectives in the Archaeology of Ghana. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-9988-8602-6-4.

- "Ghana's Kente identifies Africans – Nana Addo". www.ghanaweb.com. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Online, Peace FM. "Scenes from ADAE K3SE3: Beautiful Kente On Display - PHOTOS". www.peacefmonline.com. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Editor (26 March 2016). "Bonwire Kente Weaving Village". touringghana.com. Retrieved 20 May 2019.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Boateng, Boatema (2011). The copyright thing doesn't work here : Adinkra and Kente cloth and intellectual property in Ghana. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-7679-8. OCLC 741751637.

- Editor (26 March 2016). "Bonwire Kente Weaving Village". touringghana.com. Retrieved 11 August 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gilfoy, Peggy (1987). Patterns of life: West African strip-weaving traditions. Published for the National Museum of African Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780874744750.

- "Wrapper (kente, oyokoman adwireasu)". Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Konadu, Kwasi (2007). Indigenous medicine and knowledge in African society. Routledge. p. 30–31.

- Smith, Shea Clark (1975). "Kente Cloth Motifs". African Arts. 9 (1): 36–39. doi:10.2307/3334979. ISSN 0001-9933. JSTOR 3334979.

- Kente Cloth Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine." African Journey. projectexploration.org. 25 Sep 2007.

- Wisdom: Adinkra Symbols & Meanings. welltempered.net.

- G. F. Kojo Arthur and Robert Rowe (2001). "Akan Kente Cloths and Motifs". Akan Cultural Symbols Project. Marshall University. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- West African Wisdom: Adinkra Symbols & Meanings – Bibliography

- Lynch, Annette; Strauss, Mitchell D. (2014). Ethnic Dress in the United States: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 176. ISBN 9780759121508.

- Matory, J. Lorand (2015). Stigma and Culture: Last-Place Anxiety in Black America. University of Chicago Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780226297736.

- Boateng, Boatema (2011). The Copyright Thing Doesn't Work Here: Adinkra and Kente Cloth and Intellectual Property in Ghana. University of Minnesota Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780816670024.

- "MTN-Ghana supports Kente Festival with cash, products". www.myjoyonline.com. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Lee, Alicia (8 June 2020). "Congressional Democrats criticized for wearing Kente cloth at event honoring George Floyd". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Griggs, Brandon (14 January 2016). "Once again, #OscarsSoWhite". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kente. |

.svg.png)