Oualata

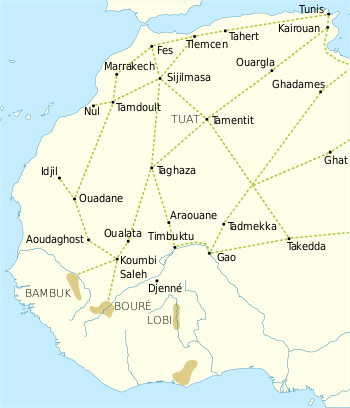

Oualata or Walata (Arabic: ولاته) (also Biru in 17th century chronicles)[2] is a small oasis town in southeast Mauritania, located at the eastern end of the Aoukar basin. Oualata was important as a caravan city in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as the southern terminus of a trans-Saharan trade route and now it is a World Heritage Site.

Oualata ولاته | |

|---|---|

Commune and town | |

View of the town looking in a southeasterly direction | |

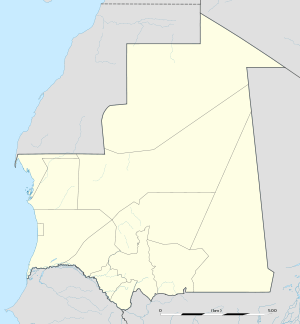

Oualata Location in Mauritania | |

| Coordinates: 17.3°N 7.025°W | |

| Country | Mauritania |

| Region | Hodh Ech Chargui |

| Population (2000)[1] | |

| • Total | 11,779 |

| Official name | Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1996 (20th session) |

| Reference no. | 750 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Arab States |

History

Oualata is believed to have been first settled by an agro-pastoral people akin to the Mandé Soninke people who lived along the rocky promontories of the Tichitt-Oualata and Tagant cliffs of Mauritania facing the Aoukar basin. There, they built what are among the oldest stone settlements on the African continent.[3]

The town formed part of the Ghana Empire and grew wealthy through trade. At the beginning of the thirteenth century Oualata replaced Aoudaghost as the principal southern terminus of the trans-Saharan trade and developed into an important commercial and religious centre.[4] By the fourteenth century the city had become part of the Mali Empire.

An important trans-Saharan route began at Sijilmasa and passed through Taghaza with its salt mines and ended at Oualata.

Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta found the inhabitants of Oualata were Muslim and mainly Massufa, a section of the Sanhaja. He was surprised by the great respect and independence that women enjoyed. He only gives a brief description of the town itself: "My stay at Iwalatan (Oualata) lasted about fifty days; and I was shown honour and entertained by its inhabitants. It is an excessively hot place, and boasts a few small date-palms, in the shade of which they sow watermelons. Its water comes from underground waterbeds at that point, and there is plenty of mutton to be had."[5] The town's original Mande name Biru had already shifted to the Berber Iwalatan, a reflection of the changing identity of the residents. This would change again with the town's Arabization, and the development of the current name, Walata.[6]

From the second half of the fourteenth century Timbuktu gradually replaced Oualata as the southern terminus of the trans-Sahara route and Oualata declined in importance.[7][8] The Berber diplomat, traveller and author, Leo Africanus, who visited the region in 1509-1510 gives a description in his book Descrittione dell’Africa: "Walata Kingdom: This is a small kingdom, and of mediocre condition compared to the other kingdoms of the blacks. In fact, the only inhabited places are three large villages and some huts spread about among the palm groves."[9][10]

The old town covers an area of about 600 m by 300 m, some of it now in ruins.[11] The sandstone buildings are coated with banco and some are decorated with geometric designs. The mosque now lies on the eastern edge of the town but in earlier times may have been surrounded by other buildings. The French historian, Raymond Mauny, estimated that in the Middle Ages the town would have accommodated between 2000 and 3000 inhabitants.[11] Today, Oualata is home to a manuscript museum, and is known for its highly decorative vernacular architecture. It was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 together with Ouadane, Chinguetti and Tichitt.[12]

Gallery

Oualata Decorative Entrance

Oualata Decorative Entrance Oualata Mosque

Oualata Mosque Oualata Decorative Window

Oualata Decorative Window Oualata Decorative Secondary Entrance

Oualata Decorative Secondary Entrance Oualata Decorative Secondary Entrance

Oualata Decorative Secondary Entrance Oualata Decorative Main Entrance

Oualata Decorative Main Entrance View of Oualata 1

View of Oualata 1 View of Oualata 2

View of Oualata 2 View of Oualata 3

View of Oualata 3 View of Oualata 4

View of Oualata 4

See also

- En attendant les hommes, 2007 documentary film about women muralists in Oualata.

References

- Résultats du RGPH 2000 des Wilayas, archived from the original on 2012-07-18

- Hunwick 1999, p. 9 n4. Walata is the arabized form of the Manding wala meaning a "shady place" while Biru is the Soninke word and has a similar meaning.

- Holl 2009.

- Levtzion 1973, p. 147.

- Gibb 1929, p. 320.

- Cleaveland 2002, p. 37.

- Levtzion 1973, p. 80, 158.

- Mauny 1961, p. 432.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 275.

- Today there is a deserted settlement called Tizert at a distance of 5 km from the town.

- Mauny 1961, p. 485.

- "Ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata". UNESCO: World Heritage Convention. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

References

- Cleaveland, Timothy (2002). Becoming Walata: A History of Saharan Social Formation and Transformation. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-325-07027-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibb, H.A.R. translator and editor (1929). Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354. London: Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Extracts are available here.

- Holl, Augustin F.C. (2009). "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, (ca. 4000–2300 BP)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 341: 703–712. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunwick, John O. (1999). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11207-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mauny, Raymond (1961). Tableau géographique de l'ouest africain au moyen age, d’après les sources écrites, la tradition et l'archéologie (in French). Dakar: Institut français d'Afrique Noire.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000) [1981]. Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa. New York, NY: Marcus Weiner Press. ISBN 1-55876-241-8.

- Mauny, Raymond (1971). "The Western Sudan". In Shinnie, Peter L. (ed.). The African Iron Age. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. 66–87. ISBN 0-19-813158-5.

- Monteil, Charles (1953). "La Légende du Ouagadou et l'Origine des Soninké". Mélanges Ethnologiques. Mémoires de l’Institut Francais de l’Afrique Noir 23. Dakar. pp. 360–408.

- Norris, H.T. (1993). "Mūrītāniyā". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. p. 625. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

External links

- Map showing Oualata: Fond Typographique 1:200,000, République Islamique de Mauritanie Sheet NE-29-XI.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oualata. |