Igbo people

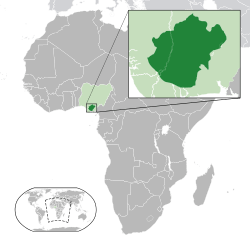

The Igbo people (English: /ˈiːboʊ/ EE-boh,[4][5] also US: /ˈɪɡboʊ/;[6][7] also spelled Ibo[8][9] and formerly also Iboe, Ebo, Eboe,[10] Eboans,[11] Heebo;[12]

natively Ṇ́dị́ Ìgbò [ìɡ͡bò] (![]()

Ṇ́dị́ Ìgbò | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| c. 45 million (2020 est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Primarily Christianity, sometimes syncretised with indigenous Igbo religion and belief systems, [3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ibibio, Efik, Annang, Ogoni, Idoma, Igala, Urhobo, Ijaw, Ogoja; more remotely the YEAI group within Volta-Niger |

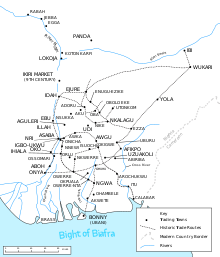

The Igbo language is a part of the Niger-Congo language family. It is divided into numerous regional dialects, and somewhat mutually intelligible with the larger "Igboid" cluster.[18] The Igbo homeland straddles the lower Niger River, east and south of the Edoid and Idomoid groups, and west of the Ibibioid (Cross River) cluster.

In rural Nigeria, Igbo people work mostly as craftsmen, farmers and traders. The most important crop is the yam.[19] Other staple crops include cassava and taro.[20]

Before British colonial rule in the 20th century, the Igbo were a politically fragmented group, with a number of centralized chiefdoms such as Nri, Aro Confederacy, Agbor and Onitsha.[21] Frederick Lugard introduced the Eze system of "Warrant Chiefs".[22] Unaffected by the Fulani War and the resulting spread of Islam in Nigeria in the 19th century, they became overwhelmingly Christian under colonization. In the wake of decolonisation, the Igbo developed a strong sense of ethnic identity.[20] During the Nigerian Civil War of 1967–1970 the Igbo territories seceded as the short-lived Republic of Biafra.[23] MASSOB, a sectarian organization formed in 1999, continues a non-violent struggle for an independent Igbo state.[24]

Large ethnic Igbo populations are found in Cameroon,[25] Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea,[26] as well as outside Africa.

Definition and subgroups

| Part of a series on |

| Igbo people |

|---|

|

| Subgroups |

|

Anioma · Agbo · Aro · Edda · Ekpeye Etche · Ezza · Ika · Ikwerre · Ikwo Ishielu · Izzi · Mbaise · Mgbo · Ngwa Nkalu · Nri-Igbo · Ogba · Ohafia Ohuhu · Omuma · Onitsha Oratta · Ubani · Ukwuani List of Igbo people |

| Igbo culture |

|

Art · Performing arts Dress · Education · Flag Calendar · Cuisine · Language Literature · Music (Ogene, Igbo Highlife) Odinani (religion) · New Yam Festival |

| Diaspora |

|

United States · Jamaica · Japan Trinidad and Tobago Canada · United Kingdom · Saros |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Igbo · Igboid · Delta Igbo Enuani Igbo · Ika Igbo Ikwerre · Ukwuani · names |

| Politics (History) |

|

List of rulers of Nri · Biafra MASSOB · Anti-Igbo sentiment Eastern Nigeria · Nigeria |

| Geography |

|

States (Nigeria): Onicha · Enugwu · Aba Ugwu Ọcha · Owerre · Ahaba Abakiliki |

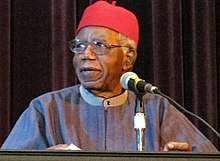

"Igbo" as an ethnic identity developed comparatively recently, in the context of decolonisation and the Nigerian Civil War. The various Igbo-speaking communities were historically fragmented and decentralised;[27] in the opinion of Chinua Achebe (2000), Igbo identity should be placed somewhere between a "tribe" and a "nation".[28] Since the defeat of the Republic of Biafra in 1970, the Igbo are sometimes classed as a "stateless nation".[29]

History

Prehistory

The Igboid languages form a cluster within the Volta–Niger phylum, most likely grouped with Yoruboid and Edoid.[30] The greatest differentiation within the Igboid group is between the Ekpeye and the rest. Williamson (2002) argues that based on this pattern, proto-Igboid migration would have moved down the Niger from a more northern area in the savannah and first settled close to the delta, with a secondary center of Igbo proper more to the north, in the Awka area.[31]

Pottery dated at around 2500 BC showing similarities with later Igbo work was found at Nsukka in the 1970s, along with pottery and tools at nearby Ibagwa; the traditions of the Umueri clan have as their source the Anambra valley. In the 1970s the Owerri, Okigwe, Orlu, Awgu, Udi and Awka divisions were determined to constitute "an Igbo heartland" from the linguistic and cultural evidence.[32]

Genetic studies have shown the Igbo to cluster most closely with other Niger-Congo-speaking peoples.[33] The predominant Y-chromosmoal haplogroup is E1b1a1-M2.[34]

Nri Kingdom

The Nri people of Igbo land have a creation myth which is one of the many creation myths that exist in various parts of Igbo land. The Nri and Aguleri people are in the territory of the Umueri clan who trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure Eri.[36] Eri's origins are unclear, though he has been described as a "sky being" sent by Chukwu (God).[36][37] He has been characterized as having first given societal order to the people of Anambra.[37] The historian Elizabeth Allo Isichei says "Nri and Aguleri and part of the Umueri clan, [are] a cluster of Igbo village groups which traces its origins to a sky being called Eri."[38]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Nri influence in Igboland may go back as far as the 9th century,[39] and royal burials have been unearthed dating to at least the 10th century. Eri, the god-like founder of Nri, is believed to have settled the region around 948 with other related Igbo cultures following after in the 13th century.[40] The first Eze Nri (King of Nri) Ìfikuánim followed directly after him. According to Igbo oral tradition, his reign started in 1043.[41] At least one historian puts Ìfikuánim's reign much later, around 1225 AD.[42]

Each king traces his origin back to the founding ancestor, Eri. Each king is a ritual reproduction of Eri. The initiation rite of a new king shows that the ritual process of becoming Ezenri (Nri priest-king) follows closely the path traced by the hero in establishing the Nri kingdom.

- — E. Elochukwu Uzukwu[43]

The Kingdom of Nri was a religio-polity, a sort of theocratic state, that developed in the central heartland of the Igbo region.[40] The Nri had seven types of taboos which included human (such as the birth of twins), animal (such as killing or eating of pythons),[45] object, temporal, behavioral, speech and place taboos.[46] The rules regarding these taboos were used to educate and govern Nri's subjects. This meant that, while certain Igbo may have lived under different formal administration, all followers of the Igbo religion had to abide by the rules of the faith and obey its representative on earth, the Eze Nri.[46][47]

Traditional society

Traditional Igbo political organization was based on a quasi-democratic republican system of government. In tight knit communities, this system guaranteed its citizens equality, as opposed to a feudalist system with a king ruling over subjects.[48] This government system was witnessed by the Portuguese who first arrived and met with the Igbo people in the 15th century.[49] With the exception of a few notable Igbo towns such as Onitsha, which had kings called Obi, and places like the Nri Kingdom and Arochukwu, which had priest kings; Igbo communities and area governments were overwhelmingly ruled solely by a republican consultative assembly of the common people.[48] Communities were usually governed and administered by a council of elders.[50]

Although title holders were respected because of their accomplishments and capabilities, they were never revered as kings, but often performed special functions given to them by such assemblies. This way of governing was immensely different from most other communities of Western Africa, and only shared by the Ewe of Ghana. Umunna are a form of patrilineage maintained by the Igbo. Law starts with the Umunna which is a male line of descent from a founding ancestor (who the line is sometimes named after) with groups of compounds containing closely related families headed by the eldest male member. The Umunna can be seen as the most important pillar of Igbo society.[52][53][54] It was also a culture in which gender was re-constructed and performed according to social need, “where gender and sex did not coincide. Instead, gender was flexible and fluid, allowing women to become men and men to become women” [55]

Mathematics in indigenous Igbo society is evident in their calendar, banking system and strategic betting game called Okwe.[56] In their indigenous calendar, a week had four days, a month consisted of seven weeks and 13 months made a year. In the last month, an extra day was added.[57][58] This calendar is still used in indigenous Igbo villages and towns to determine market days.[59] They settled law matters via mediators, and their banking system for loans and savings, called Isusu, is also still used.[60] The Igbo new year, starting with the month Ọ́nwạ́ M̀bụ́ (Igbo: First Moon) occurs on the third week of February,[61] although the traditional start of the year for many Igbo communities is around springtime in Ọ́nwạ́ Ágwụ́ (June).[62][63] Used as a ceremonial script by secret societies, the Igbo have an indigenous ideographic set of symbols called Nsibidi, originating from the neighboring Ejagham people.[64] Igbo people produced bronzes from as early as the 9th century, some of which have been found at the town of Igbo Ukwu, Anambra state.[35]

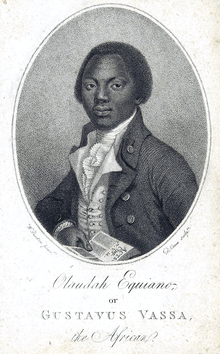

A system of indentured servitude existed among the Igbo before and after the encounter with Europeans.[65][66] Indentured service in Igbo areas was described by Olaudah Equiano in his memoir. He describes the conditions of the slaves in his community of Essaka, and points out the difference between the treatment of slaves under the Igbo in Essaka, and those in the custody of Europeans in West Indies:

...but how different was their condition from that of the slaves in the West Indies! With us, they do no more work than other members of the community,... even their master;... (except that they were not permitted to eat with those... free-born;) and there was scarce any other difference between them,... Some of these slaves have... slaves under them as their own property... for their own use.[66]

The Niger coast became an area of contact between African and European traders in 1434. The Portuguese were the first to make contact with the Igbo people. At this time in history, there was more of an emphasis on trade as opposed to empire building; consequently, the Portuguese engaged in trading Igbo slaves. Then the Dutch came into the picture, and finally the British after that.[67] The slave trade ended in 1807, so the Europeans started to shift their focus away from trade and into industry. The British, in particular, sought to extend their imperialistic influence into Igboland.[14]

Prior to European contact, Igbo trade routes stretched as far as Mecca, Medina and Jeddah on the continent.[68]

Transatlantic slave trade and diaspora

.jpg)

Chambers (2002) argued that many of the slaves taken from the Bight of Biafra across the Middle Passage would have been Igbo.[74] These slaves were usually sold to Europeans by the Aro Confederacy, who kidnapped or bought slaves from Igbo villages in the hinterland.[75] Igbo slaves may have not been victims of slave-raiding wars or expeditions, but perhaps debtors or Igbo people who committed within their communities alleged crimes.[76] With the goal for freedom, enslaved Igbo people were known to the British colonists as being rebellious and having a high rate of suicide to escape slavery.[77][78][79] There is evidence that traders sought Igbo women.[80][81] Igbo women were paired with Coromantee (Akan) men to subdue the men because of the belief that the women were bound to their first-born sons’ birthplace.

It is alleged that European slave traders were fairly well informed about various African ethnicities, leading to slavers' targeting certain ethnic groups which plantation owners preferred. Particular desired ethnic groups consequently became fairly concentrated in certain parts of the Americas.[82] The Igbo were dispersed to colonies such as Jamaica,[10] Cuba,[10] Saint-Domingue,[10] Barbados,[83] the future United States,[84] Belize[85] and Trinidad and Tobago,[86] among others.

Elements of Igbo culture can still be found in these places. For example, in Jamaican Patois, the Igbo word unu, meaning "you" plural, is still used.[87] "Red Ibo" (or "red eboe") describes a black person with fair or "yellowish" skin. This term had originated from the reported prevalence of these skin tones among the Igbo but eastern Nigerian influences may not be strictly Igbo.[88] The word Bim, a colloquial term for Barbados, was commonly used among enslaved Barbadians (Bajans). This word is said to have derived from bém in the Igbo language meaning 'my place or people', but may have other origins (see: Barbados etymology).[89][90] A section of Belize City was named Eboe Town after its Igbo inhabitants.[91] In the United States, the Igbo were imported to the Chesapeake Bay colonies and states of Maryland and Virginia, where they constituted the largest group of Africans.[92][93] Since the late 20th century, a wave of Nigerian immigrants, mostly English and Igbo-speaking, have settled in Maryland, attracted to its strong professional job market.[94] They were also imported to the southern borders of Georgia and South Carolina considered the low country and where Gulluh culture still preserves African traditions of its ancestors. Today, there is an area called Ebo landing . The story surrounding the name is how Igbo were brought to the area and when they got off of the ship, they collectively tried to drown themselves rather than be slaves. That point is on Igbo landing.

Colonial period

The 19th-century British colonization effort in present-day Nigeria and increased encounters between the Igbo and other ethnicities near the Niger River led to a deepening sense of a distinct Igbo ethnic identity. The Igbo proved decisive and enthusiastic in their embrace of Christianity and Western education.[95][96] Due to the incompatibility of the Igbo decentralized style of government and the centralized system including the appointment of warrant chiefs required for British indirect rule, British colonial rule was marked with open conflicts and much tension.[65] Under British colonial rule, the diversity within each of Nigeria's major ethnic groups slowly decreased and distinctions between the Igbo and other large ethnic groups, such as the Hausa and the Yoruba, became sharper.[97]

Colonial rule transformed Igbo society, as portrayed in Chinua Achebe's novel Things Fall Apart. British rule brought about changes in culture, such as the introduction of Warrant Chiefs as Eze (indigenous rulers) where there were no such monarchies.[98] Christian missionaries introduced aspects of European ideology into Igbo society and culture, sometimes shunning parts of the culture.[99] The rumours that the Igbo women were being assessed for taxation sparked off the 1929 Igbo Women's War in Aba (also known as the 1929 Aba Riots), a massive revolt of women never encountered before in Igbo history.[100]

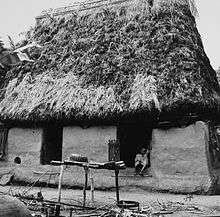

Aspects of Igbo culture such as construction of houses, education and religion changed following colonialism. The tradition of building houses out of mud walls and thatched roofs ended as the people shifted to materials such as cement blocks for houses and zinc roofs. Roads for vehicles were built. Buildings such as hospitals and schools were erected in many parts of Igboland. Along with these changes, electricity and running water were installed in the early 20th century. With electricity, new technology such as radios and televisions were adopted, and have become commonplace in most Igbo households.[101]

Nigerian Civil War

A series of ethnic clashes between Northern Muslims and the Igbo, and other ethnic groups of Eastern Nigeria Region living in Northern Nigeria took place between 1966 and 1967. Elements in the army had assassinated the Nigerian military head of state General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi (29 July 1966)[102] and peace negotiations failed between the military government that deposed Ironsi and the regional government of Eastern Nigeria at the Aburi Talks in Ghana in 1967.[103] These events led to a regional council of the peoples of Eastern Nigeria deciding that the region should secede and proclaim the Republic of Biafra on May 30, 1967.[104] Late General Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu made this declaration and became the head of state of the new republic.[105] The resultant war, which became known as the Nigerian Civil War or the Nigerian-Biafran War, lasted from July 6, 1967 until January 15, 1970, after which the federal government re-absorbed Biafra into Nigeria.[104][106] Several million Eastern Nigerians died from the pogroms against them, such as the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom where between 10,000 and 30,000 Igbo people were killed.[107][108] Many homes, schools, and hospitals were destroyed in the conflict, as well. On top of this, the federal government of Nigeria denied Igbo people access to their savings placed in Nigerian banks and provided them with little compensation. The war also led to a great deal of discrimination against the Igbo people at the hands of other ethnic groups.[109]

In their struggle, the people of Biafra earned the respect of figures such as Jean-Paul Sartre and John Lennon, who returned his British honor, MBE, partly in protest against British collusion in the Nigeria-Biafra war.[110] The former President of Biafra, late General Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, stated that the three years of freedom allowed his people to become the most civilized and most technologically-advanced black people in the world.[109] In July 2007, Odumegwu-Ojukwu renewed calls for the secession of the Biafran state as a sovereign entity.[111]

Recent history (1970 to present)

Some Igbo subgroups, such as the Ikwerre, started dissociating themselves from the larger Igbo population after the war.[112] In the post-war era, people of eastern Nigeria changed the names of both people and places to non-Igbo-sounding words. For instance, the town of Igbuzo was anglicized to Ibusa.[113] Due to discrimination, many Igbo had trouble finding employment, and during the early 1970s, the Igbo became one of the poorest ethnic groups in Nigeria.[114][115][116]

Igbo rebuilt their cities by themselves without any contribution from the Federal government of Nigeria. This led to the establishment of new factories in southern Nigeria. Many Igbo people eventually took government positions,[117] although many were engaged in private business.[118] Since the early 21st century, there has been a wave of Nigerian Igbo immigration to other African countries, Europe, and the Americas.[119]

Archives

A series of black and white, silent films about the Igbo people made by George Basden in the 1920s and 1930s are held in the British Empire and Commonwealth Collection at Bristol Archives (Ref. 2006/070).[120]

Political organization

The 1930s saw the rise of Igbo unions in the cities of Lagos and Port Harcourt. Later, the Ibo Federal Union (renamed the Ibo State Union in 1948) emerged as an umbrella pan-ethnic organization. Headed by Nnamdi Azikiwe, it was closely associated with the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC), which he co-founded with Herbert Macaulay. The aim of the organization was the improvement and advancement (such as in education) of the Igbo and their indigenous land and included an Igbo "national anthem" with a plan for an Igbo bank.[121][122]

In 1978 after Olusegun Obasanjo's military regime lifted the ban on independent political activity, the Ohanaeze Ndigbo organization was formed, an elite umbrella organization which speaks on behalf of the Igbo people.[123][124] Their main concerns are the marginalization of the Igbo people in Nigerian politics and the neglect of indigenous Igbo territory in social amenities and development of infrastructure. Other groups which protest the perceived marginalization of the Igbo people are the Igbo Peoples Congress (IPC).[125] Even before the 20th century there were numerous Igbo unions and organizations existing around the world, such as the Igbo union in Bathurst, Gambia in 1842, founded by a prominent Igbo trader and ex-soldier named Thomas Refell. Another was the union founded by the Igbo community in Freetown, Sierra Leone by 1860, of which Africanus Horton, a surgeon, scientist and soldier, was an active member.[126]

Decades after the Nigerian-Biafran war, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB), a secessionist group, was founded in September 1999 by Ralph Uwazurike for the goal of an independent Igbo state. Since its creation, there have been several conflicts between its members and the Nigerian government, resulting in the death of members.[125][127][128] After the 2015 Nigerian general elections a group known as the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) became the most prominent vocal group for the agitation of the creation of an independent state of Biafra through a radio station named Radio Biafra.[129][130][131] For the promotion of the Igbo language and culture, the Society for Promoting Igbo Language and Culture (SPILC) was founded in 1949 by Frederick Chidozie Ogbalu, and has since created a standard dialect for Igbo.[132][133]

Culture

Igbo culture includes the various customs, practices and traditions of the people. It comprises archaic practices as well as new concepts added into the Igbo culture either through evolution or outside influences. These customs and traditions include the Igbo people's visual art, use of language, music and dance forms, as well as their attire, cuisine and language dialects. Because of their various subgroups, the variety of their culture is heightened further.

Language and literature

The Igbo language was used by John Goldsmith as an example to justify deviating from the classical linear model of phonology as laid out in The Sound Pattern of English. It is written in the Roman script as well as the Nsibidi formalized ideograms, which is used by the Ekpe society and Okonko fraternity, but is no longer widely used.[136] Nsibidi ideography existed among the Igbo before the 16th century, but died out after it became popular among secret societies, who made Nsibidi a secret form of communication.[137] Igbo language is difficult because of the huge number of dialects, its richness in prefixes and suffixes and its heavy intonation.[138] Igbo is a tonal language and there are hundreds of different Igbo dialects and Igboid languages, such as the Ikwerre and Ekpeye languages.[18] In 1939, Dr. Ida C. Ward led a research expedition on Igbo dialects which could possibly be used as a basis of a standard Igbo dialect, also known as Central Igbo. This dialect included that of the Owerri and Umuahia groups, including the Ohuhu dialect. This proposed dialect was gradually accepted by missionaries, writers, publishers, and Cambridge University.[139]

In 1789, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano was published in London, England, written by Olaudah Equiano, a former slave. The book featured 79 Igbo words.[140] In the first and second chapter, the book illustrates various aspects of Igbo life based on Olaudah Equiano's life in his hometown of Essaka.[141] Although the book was one of the first books published to include Igbo material, Geschichte der Mission der evangelischen Brüder auf den caraibischen Inseln St. Thomas, St. Croix und S. Jan (German: History of the Evangelical Brothers' Mission in the Caribbean Islands St. Thomas, St. Croix and St. John),[142] published in 1777, written by the German missionary C. G. A. Oldendorp, was the first book to publish any Igbo material.[140]

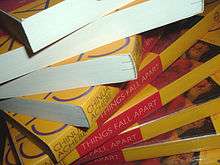

Perhaps the most popular and renowned novel that deals with the Igbo and their traditional life was the 1959 book by Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart. The novel concerns influences of British colonialism and Christian missionaries on a traditional Igbo community during an unspecified time in the late nineteenth or early 20th century. Most of the novel is set in Umuofia, one of nine villages on the lower Niger.[143]

Performing arts

The Igbo people have a musical style into which they incorporate various percussion instruments: the udu, which is essentially designed from a clay jug; an ekwe, which is formed from a hollowed log; and the ogene, a hand bell designed from forged iron. Other instruments include opi, a wind instrument similar to the flute, igba, and ichaka.[144] Another popular musical form among the Igbo is Highlife. A widely popular musical genre in West Africa, Highlife is a fusion of jazz and traditional music. The modern Igbo highlife is seen in the works of Dr Sir Warrior, Oliver De Coque, Bright Chimezie and Chief Osita Osadebe, who were among the most popular Igbo highlife musicians of the 20th century.[145]

Masking is one of the most common art styles in Igboland and is linked strongly with Igbo traditional music. A mask can be made of wood or fabric, along with other materials including iron and vegetation.[146] Masks have a variety of uses, mainly in social satires, religious rituals, secret society initiations (such as the Ekpe society) and public festivals, which now include Christmas time celebrations.[147] Some of the best known include the Agbogho Mmuo (Igbo: Maiden spirit) masks of the Northern Igbo which represent the spirits of deceased maidens and their mothers with masks symbolizing beauty and Ijele.[146]

Other impressive masks include Northern Igbo Ijele masks. At 12 feet (3.7 m) high, Ijele masks consist of platforms 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter,[146] supporting figures made of coloured cloth and representing everyday scenes with objects such as leopards. Ijele masks are used for honoring the dead to ensure the continuity and well-being of the community and are only seen on rare occasions such as the death of a prominent figure in the community.[146]

There are many Igbo dance styles, but perhaps, Igbo dance is best known for its Atilogwu dance troops. These performances include acrobatic stunts such as high kicks and cartwheels, with each rhythm from the indigenous instruments indicating a movement to the dancer.[148]

Visual art and architecture

There is such variety among Igbo groups that it is not possible to define a general Igbo art style.[146] Igbo art is known for various types of masquerade, masks and outfits symbolising people, animals, or abstract conceptions. Bronze castings found in the town of Igbo Ukwu from the 9th century, constitute the earliest sculptures discovered in Igboland. Here, the grave of a well-established man of distinction and a ritual store, dating from the 9th century AD, contained both chased copper objects and elaborate castings of leaded bronze.[35] Along with these bronzes were 165,000 glass beads said to have originated in Egypt, Venice and India.[149] Some popular Igbo art styles include Uli designs. The majority of the Igbo carve and use masks, although the function of masks vary from community to community.[150]

Igbo art is noted for Mbari architecture.[150]

Mbari houses of the Owerri-Igbo are large opened-sided square planned shelters. They house many life-sized, painted figures (sculpted in mud to appease the Alusi (deity) and Ala, the earth goddess, with other deities of thunder and water).[151] Other sculptures are of officials, craftsmen, foreigners (mainly Europeans), animals, legendary creatures and ancestors.[151] Mbari houses take years to build in what is regarded as a sacred process. When new ones are constructed, old ones are left to decay.[151] Everyday houses were made of mud and thatched roofs with bare earth floors with carved design doors. Some houses had elaborate designs both in the interior and exterior. These designs could include Uli art designed by Igbo women.[152]

One of the unique structures of Igbo culture was the Nsude Pyramids, at the town of Nsude, in Abaja, northern Igboland. Ten pyramidal structures were built of clay/mud. The first base section was 60 ft. in circumference and 3 ft. in height. The next stack was 45 ft. in circumference. Circular stacks continued, till it reached the top. The structures were temples for the god Ala/Uto, who was believed to reside at the top. A stick was placed at the top to represent the god's residence. The structures were laid in groups of five parallel to each other. Because it was built of clay/mud like the Deffufa of Nubia, time has taken its toll requiring periodic reconstruction.[153]

Religion and rites of passage

Christianity was first introduced to the Igbo people through European colonization in 1857. The Igbo people were hesitant to convert to Christianity initially because they believed the gods of their native religion would bring disaster to them. However, Christianity gradually gained converts in Igbo land, mainly through the work of church agents. These men built schools and focused on persuading the youth to adopt Christian values.[155] The Igbo people today are known as the ethnic group that has adopted Christianity the most in all of Africa.[156]

The Igbo people were unaffected by the Islamic jihad waged in Nigeria in the 19th century, but a small minority converted to Islam in the 20th century. [3] There is also a small population of Igbo Jews,[157] some of whom merely identifying as Jews, while others having converted to Judaism. These draw their inspiration from Olaudah Equiano, a Christian-educated freed slave who remarked in his autobiography of 1789 on "the strong analogy which... appears to prevail in the manners and customs of my countrymen and those of the Jews, before they reached the Land of Promise, and particularly the patriarchs while they were yet in that pastoral state which is described in Genesis—an analogy, which alone would induce me to think that the one people had sprung from the other." Equiano's speculation has given rise to a great debate on the origins of the Igbo.

Native religion

The Igbo traditional religion is known as Odinani.[36] The supreme deity is called Chukwu ("great spirit"); Chukwu created the world and everything in it and is associated with all things on Earth. They believe the Cosmos is divided into four complex parts: creation, known as Okike; supernatural forces or deities called Alusi; Mmuo, which are spirits; and Uwa, the world.[158]

Chukwu is the supreme deity in Odinani as he is the creator, and the Igbo people believe that all things come from him[159] and that everything on earth, heaven and the rest of the spiritual world is under his control.[160] Linguistic studies of the Igbo language suggest that the name Chukwu is a compound of the Igbo words Chi (spiritual being) and Ukwu (great in size).[161] Each individual is born with a spiritual guide/guardian angel or guardian principle, "Chi", unique to each individual and the individual's fate and destiny is determined by their Chi. Thus the Igbos say that the siblings may come of the same mother but no two people have the same Chi and thus different destinies for all. Alusi, alternatively known as Arusi or Arushi (depending on dialect), are minor deities that are worshiped and served in Odinani. There are many different Alusi, each with its own purpose. When an individual deity is no longer needed, or becomes too violent, it is discarded.[162]

The Igbo have traditionally believed in reincarnation. People are believed to reincarnate into families that they were part of while alive. Before a relative dies, it is said that the soon to be deceased relative sometimes give clues of who they will reincarnate as in the family. Once a child is born, he or she is believed to give signs of who they have reincarnated from. This can be through behavior, physical traits and statements by the child. A diviner can help in detecting who the child has reincarnated from. It is considered an insult if a male is said to have reincarnated as a female.[163]

Children are not allowed to call elders by their names without using an honorific (as this is considered disrespectful). As a sign of respect, children are required to greet elders when seeing them for the first time in the day. Children usually add the Igbo honorifics Mazi or Dede before an elder's name when addressing them.[164][165]

Burials

After a death, the body of a prominent member of society is placed on a stool in a sitting posture and is clothed in the deceased's finest garments. Animal sacrifices may be offered and the dead person is well perfumed.[166] Burial usually follows within 24 hours of death. In the 21st century, the head of a home is usually buried within the compound of his residence.[165] Different types of deaths warrant different types of burials. This is determined by an individual's age, gender and status in society. Children are buried in hiding and out of sight; their burials usually take place in the early mornings and late nights. A simple untitled man is buried in front of his house and a simple mother is buried in her place of origin: in a garden or a farm-area that belonged to her father.[167] In the 21st century, a majority of the Igbo bury their dead in the western way, although it is not uncommon for burials to be practiced in the traditional Igbo ways.[168]

Marriage

The process of marrying usually involves asking the young woman's consent, introducing the woman to the man's family and the same for the man to the woman's family, testing the bride's character, checking the woman's family background, and paying the brides' wealth.[169] Typically speaking, bride wealth is more symbolic. Nonetheless, kola nuts, wine, goats, and chickens, among other things, are listed in the proposal, as well. Negotiating the bride wealth can also take more than one day, giving both parties time for a ceremonial feast.[170] Marriages were sometimes arranged from birth through negotiation of the two families.[171] However, after a series of interviews conducted in the 1990s with 250 Igbo women, it was found that 94.4% of that sample population disapproved of arranged marriages.[172]

In the past, many Igbo men practiced polygamy. The polygamous family is made up of a man and his wives and all their children.[165] Men sometimes married multiple wives for economic reasons so as to have more people in the family, including children, to help on farms.[173] Christian and civil marriages have changed the Igbo family since colonization. Igbo people now tend to enter monogamous courtships and create nuclear families, mainly because of Western influence.[174] Some Western marriage customs, such as weddings in a church, take place either before or after the lgbo cultural traditional marriage.[175]

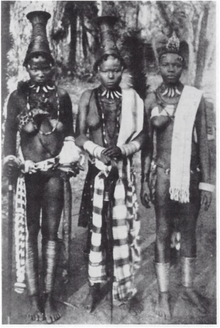

Attire

Traditionally, the attire of the Igbo generally consisted of little clothing, as the purpose of clothing originally was simply to conceal private parts. Because of this purpose, children were often nude from birth until the beginning of their adolescence—the time they were considered to have something to hide.[176]Uli body art was used to decorate both men and women in the form of lines forming patterns and shapes on the body.[177]

Women traditionally carry their babies on their backs with a strip of clothing binding the two with a knot at her chest, a practice used by many ethnic groups across Africa.[178] This method has been modernized in the form of the child carrier. Maidens usually wore a short wrapper with beads around their waist and other ornaments such as necklaces and beads.[178] Both men and women wore wrappers.[177][178] Men would wear loin cloths that wrapped round their waist and between their legs to be fastened at their back, the type of clothing appropriate for the intense heat as well as jobs such as farming.[177][178]

In Olaudah Equiano's narrative, Equiano describes fragrances that were used by the Igbo in the community of Essaka:

Our principal luxury is in perfumes; one sort of these is an odoriferous wood of delicious fragrance: the other a kind of earth; a small portion of which thrown into the fire diffuses a most powerful odor. We beat this wood into powder, and mix it with palm oil; with which both men and women perfume themselves.

As colonialism became more influential, the Igbo adapted their dress customs.[180] Clothing worn before colonialism became "traditional" and worn on cultural occasions. Modern Igbo traditional attire, for men, is generally made up of the Isiagu top, which resembles the Dashiki worn by other African groups. Isiagu (or Ishi agu) is usually patterned with lions' heads embroidered over the clothing and can be a plain colour.[181] It is worn with trousers and can be worn with either a ceremonial title holders hat or with the conventional striped men's hat known as Okpu Agu.[182] For women, a puffed sleeve blouse along with two wrappers and a head tie are worn.[178][180]

Cuisine

The yam is very important to the Igbo as the staple crop. It is known for its resiliency (a yam can remain fully edible for six months without refrigeration), but it can also be very versatile in terms of its incorporation into different dishes.[184] Yams can be fried, roasted, boiled, or made into a potage with tomatoes and herbs. The cultivation of yams is most commonly carried out by men, as women tend to focus on other crops.[185]

There are celebrations such as the New yam festival (Igbo: Iwaji) which are held for the harvesting of the yam.[19] During the festival, yam is eaten throughout the communities as celebration. Yam tubers are shown off by individuals as a sign of success and wealth.[186] Rice has replaced yam for many ceremonial occasions. Other indigenous foods include cassava, garri, maize and plantains. Soups or stews are included in a typical meal, prepared with a vegetable (such as okra, of which the word derives from the Igbo language, Okwuru)[187] to which pieces of fish, chicken, beef, or goat meat are added. Jollof rice is popular throughout West Africa and Palm wine is a popular alcoholic traditional beverage.[188][189]

Demographics

Nigeria

The Igbo people are natively found in Abia, Akwa Ibom, Anambra, Benue, Cross River, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo, Delta and Rivers State.[190] The Igbo language is predominant throughout these areas, although Nigerian English (the national language) is spoken as well. Prominent towns and cities in Igboland include Aba, Enugu (considered the 'Igbo capital'),[191] Onitsha, Owerri, Abakaliki, Asaba, and Port Harcourt among others.[192] A significant number of Igbo people have migrated to other parts of Nigeria, such as the cities of Lagos, Abuja, and Kano.[101]

The official data on the population of ethnic groups in Nigeria continues to be controversial as a minority of these groups have claimed that the government deliberately deflates the official population of one group, to give the other numerical superiority.[193][194][195] The CIA World Factbook puts the Igbo population of Nigeria at 24% of a total population of 177 million, or approximate 42 million people.

Southeastern Nigeria, which is inhabited primarily by the Igbo, is the most densely populated area in Nigeria, and possibly in all of Africa.[196][197] Most ethnicities that inhabit southeastern Nigeria, such as the closely related Efik and Ibibio people, are sometimes regarded as Igbo by other Nigerians and ethnographers who are not well informed about the southeast.[198][199]

Diaspora

After the Nigerian-Biafran War, many Igbo people emigrated out of the indigenous Igbo homeland in southeastern Nigeria due to an absence of federal presence, lack of jobs, and poor infrastructure.[200] In recent decades the Igbo region of Nigeria has suffered from frequent environmental damage mainly related to the oil industry.[201] Igbo people have moved to both Nigerian cities such as Lagos and Abuja, and other countries such as Gabon,[202] Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. Prominent Igbo communities outside Africa include those of London in the United Kingdom and Houston, Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, Seattle, Atlanta and Washington, D.C. in the United States.[203][204][205][206]

About 21,000 Igbo people were recorded in Ghana in 1969,[207] while as small number (8,680) lived on Bioko island in 2002.[208] Small numbers live in Japan, making up the majority of the Nigerian immigrant population based in Tokyo.[209][210] A large amount of the African population of Guangdong, China, is Igbo-speaking and are mainly businessmen trading between factories in China and southeastern Nigeria, particularly Enugu.[211] Other Igbo immigrants are found in the Americas (Igbo Canadian, Igbo American and elsewhere;[212]

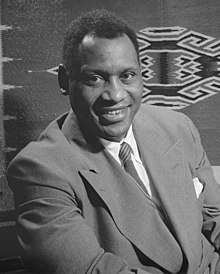

In the 2003 PBS programme African American Lives, Bishop T. D. Jakes had his DNA analyzed; his Y chromosome showed that he is descended from the Igbo.[213] American actors Forest Whitaker, Paul Robeson, and Blair Underwood have traced their genealogy back to the Igbo people.[214][215][216]

Notable people of Igbo origin

- Notable people

.jpg)

.jpg) Ngozi Okonjo Iweala

Ngozi Okonjo Iweala

Economist, member Twitter board, nominee President of World Bank

.jpg)

References

- Nigeria country profile at CIA's The World Factbook: "Igbo 20.2%" out of a population of 214 million (2020 estimate).

- PeopleGroups.org - Igbo

- UCHENDU, EGODI (1 January 2010). "BEING IGBO AND MUSLIM: THE IGBO OF SOUTH-EASTERN NIGERIA AND CONVERSIONS TO ISLAM, 1930s TO RECENT TIMES". The Journal of African History. 51 (1): 63–87. doi:10.1017/s0021853709990764. JSTOR 40985002.

- Nwangwa, Shirley Ngozi (26 November 2018). "Why It Matters That Alex Trebek Mispronounced The Name Of My People On 'Jeopardy!'". Huffington Post. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Igbo". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Igbo". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Ibo". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Isichei, Elizabeth (1978). Igbo Worlds. Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

- "Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 223.

-

- Lovejoy, Paul (2000). Identity in the Shadow of Slavery. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8264-4725-8.

- Floyd, E. Randall (2002). In the Realm of Ghosts and Hauntings. Harbor House. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-891799-06-8.

- Cassidy, Frederic Gomes; Robert Brock Le Page (2002). A Dictionary of Jamaican English (2nd ed.). University of the West Indies Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-976-640-127-6.

- Equiano, Olaudah (1837). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. I. Knapp. p. 27.

- Obichere, Boniface I. (1982). Studies in Southern Nigerian History: A Festschrift for Joseph Christopher Okwudili Anene 1918–68. Routledge. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-7146-3106-6.

- "The Native Igbo Of Equatorial Guinea". www.igbodefender.com. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- "The Igbo People - Origins & History". www.faculty.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Slattery, Katharine. "The Igbo People – Origins & History". www.faculty.ucr.edu. School of English, Queen's University of Belfast. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- Chigere, Nkem Hyginus (2000). Foreign Missionary Background and Indigenous Evangelization in Igboland: Igboland and The Igbo People of Nigeria. Transaction Publishers, USA. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-8258-4964-1. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Williams, Lizzie (2008). Nigeria: The Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-84162-239-2.

- Fardon, Richard; Furniss, Graham (1994). African languages, development and the state. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-415-09476-4. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Agwu, Kene. "Yam and the Igbos". BBC Birmingham. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- "Igbo". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- Miers, Suzanne; Roberts, Richard L. (1988). The End of slavery in Africa. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-299-11554-8.

- Falola, Toyin (2003). Adebayo Oyebade (ed.). The foundations of Nigeria: essays in honor of Toyin Falola. Africa World Press. p. 476. ISBN 978-1-59221-120-3. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- Forsythe, Frederick (2006). Shadows: Airlift and Airwar in Biafra and Nigeria 1967–1970. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-902109-63-3.

- Adekson, Adedayo Oluwakayode (2004). The "civil society" problematique: deconstructing civility and southern Nigeria's ethnic radicalization. Routledge. pp. 87, 96. ISBN 978-0-415-94785-5.

- Forrest, Tom (1994). The Advance of African Capital: The Growth of Nigerian Private Enterprise (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7486-0492-0.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2006). African Countries: An Introduction with Maps. Pan-African Books: Continental Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-620-34815-7.

- Levinson, David; Timothy J O'Leary (1995). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. G.K. Hall. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8161-1815-1.

- Achebe, Chinua (2000). Home and Exile. Oxford University Press US. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-513506-0.

...Igbo people might score poorly on the Oxford dictionary test for tribe... Now, to call them a nation... This may not be perfect for the Igbo, but it is close.

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-313-32384-3.

- Williamson & Blench (2000) 'Niger–Congo', in Heine & Nurse, African Languages.

- Kay Williamson in Ebiegberi Joe Alagoa, F. N. Anozie, Nwanna Nzewunwa (eds.), The Early History of the Niger Delta (1988) 92f.

- Elizabeth, Isichei (1976). A History of the Igbo People. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-18556-8.; excerpted in "Cultural Harmony I: Igboland—the World of Man and the World of Spirits", section 4 of Kalu Ogbaa, ed., Understanding Things Fall Apart (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999; ISBN 0-313-30294-4), pp. 83–85.

- Michael C. Campbell; Sarah A. Tishkoff (September 2008). "African Genetic Diversity: Implications for Human Demographic History, Modern Human Origins, and Complex Disease Mapping, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics" (PDF). 9. Retrieved December 22, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - M191/P86 positive samples occurred in tested populations of Annang (38.3%), Ibibio (45.6%), Efik (45%), and Igbo (54.3%). Veeramah, Krishna R; Bruce A Connell; Naser Ansari Pour; Adam Powell; Christopher A Plaster; David Zeitlyn; Nancy R Mendell; Michael E Weale; Neil Bradman; Mark G Thomas (31 March 2010). "Little genetic differentiation as assessed by uniparental markers in the presence of substantial language variation in peoples of the Cross River region of Nigeria". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 92. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-92. PMC 2867817. PMID 20356404.

- Apley, Apley. "Igbo-Ukwu (ca. 9th century)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Isichei, Elizabeth Allo (1997). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press Cambridge, UK. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-521-45599-2.

- Uzukwu, E. Elochukwu (1997). Worship as Body Language. Liturgical Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8146-6151-2.

- Isichei, Elizabeth Allo (1997). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-521-45599-2. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- Hrbek, Ivan; Fāsī, Muḥammad (1988). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. London: Unesco. p. 254. ISBN 978-92-3-101709-4.

- Lovejoy, Paul (2000). Identity in the Shadow of Slavery. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8264-4725-8.

- Onwuejeogwu, M. Angulu (1981). Igbo Civilization: Nri Kingdom & Hegemony. Ethnographica. ISBN 978-0-905788-08-1.

- Chambers, Douglas B. (2005). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia (illustrated ed.). Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-57806-706-0.

- Uzukwu, E. Elochukwu (1997). Worship as Body Language. Liturgical Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8146-6151-2.

- Basden, George Thomas (1921). Among the Ibos of Nigeria: An Account of the Curious & Interesting Habits, Customs & Beliefs of a Little Known African People, by One who Has for Many Years Lived Amongst Them on Close & Intimate Terms. Seeley, Service. p. 184.

- Hodder, Ian (1987). The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-32924-8.

- Nyang, Sulayman; Olupona, Jacob K. (1995). Religious Plurality in Africa: Essays in Honour of John S. Mbiti. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 118. ISBN 978-3-11-014789-6.

- Hodder, Ian (1987). The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-32924-8.

- Furniss, Graham; Elizabeth Gunner; Liz Gunner (1995). Power, Marginality and African Oral Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-521-48061-1.

- Chigere, Nkem Hyginus M. V. (2001). Foreign Missionary Background and Indigenous Evangelization in Igboland (illustrated ed.). LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 113. ISBN 978-3-8258-4964-1.

- Gordon, April A. (2003). Nigeria's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook (illustrated, annotated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-57607-682-8.

- Basden, George Thomas (1921). Among the Ibos of Nigeria: An Account of the Curious & Interesting Habits, Customs & Beliefs of a Little Known African People, by One who Has for Many Years Lived Amongst Them on Close & Intimate Terms. Seeley, Service. p. 96.

- Ilogu, Edmund (1974). Christianity and Ibo culture. Brill Archive. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-04-04021-2.

- Ndukaihe, Vernantius Emeka; Fonk, Peter (2006). Achievement as Value in the Igbo/African Identity: The Ethics. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 204. ISBN 978-3-8258-9929-5.

- Agbasiere, Joseph Thérèse (2000). Women in Igbo Life and Thought. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-415-22703-2. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Amadiume, Ifi (1987). Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society. London: Zed Books Ltd. pp. 23. ISBN 9781783603350.

- Chambers, Douglas B. (2005). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia (illustrated ed.). Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-57806-706-0.

- Liamputtong, Pranee (2007). Childrearing and Infant Care Issues: A Cross-cultural Perspective. Nova Publishers. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-60021-610-7.

- Holbrook, Jarita C.; R. Thebe Medupe; Johnson O. Urama (2008-01-01). African Cultural Astronomy: Current Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy Research in Africa. Springer, 2007. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-4020-6638-2.

- Holbrook, Jarita C. (2007). African Cultural Astronomy: Current Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy Research in Africa. Springer. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4020-6638-2. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Njoku, Onwuka N. (2002). Pre-colonial economic history of Nigeria. Ethiope Publishing Corporation, Benin City, Nigeria. ISBN 978-978-2979-36-0.

- Onwuejeogwu, M. Angulu (1981). An Igbo civilization: Nri kingdom & hegemony. Ethnographica. ISBN 978-978-123-105-6.

- Aguwa, Jude C. U. (1995). The Agwu deity in Igbo religion. Fourth Dimension Publishing Co., Ltd. p. 29. ISBN 978-978-156-399-7.

- Hammer, Jill (2006). The Jewish book of days: a companion for all seasons. Jewish Publication Society. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-8276-0831-3.

- Peek, Philip M.; Kwesi Yankah (2004). African Folklore: An Encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-415-93933-1.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History. CRC Press. p. 674. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6.

- Equiano, Olaudah (1837). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. I. Knapp. pp. 20–21.

- Uchendu, Victor Chikezie (1965). The Igbo of southeast Nigeria (illustrated ed.). Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-03-052475-2.

- Glenny (2008). McMaffirst=Misha. Random House. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-09-948125-6.

- Williams, Emily Allen (2004). The Critical Response to Kamau Brathwaite. Praeger Publishers. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-275-97957-7.

- "Edward Wilmot Blyden". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- "Edward Wilmot Blyden:- Father of Pan Africanism (August 3, 1832 to February 7, 1912)". Awareness Times (Sierra Leone). 2 August 2006. Archived from the original on 25 October 2005.

- Robeson II, Paul (2001). The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist's Journey, 1898–1939. Wiley. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-471-24265-9. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

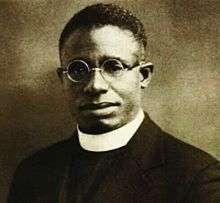

A dark-skinned man descended from the Ibo tribe of Nigeria, Reverend Robeson was of medium height with broad shoulders, and had an air of surpassing dignity.

- Azuonye, Chukwuma (1990). "Igbo Names in the Nominal Roll of Amelié, An Early 19th Century Slave Ship from Martinique: Reconstructions, Interpretations and Inferences". footnote: University of Massachusetts Boston. p. 1. Retrieved 2015-03-26.

- Chambers, D.B. (2002). "REJOINDER – The Significance of Igbo in the Bight of Biafra Slave". Slavery & Abolition. Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group. 23: 101–120. doi:10.1080/714005225. Guo, Rongxing (2006). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. Nova Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-60021-445-5.

- Douglas, Chambers B. (2005). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-57806-706-0.

- Talbot, Percy Amaury; Mulhall, H. (1962). The physical anthropology of Southern Nigeria. Cambridge University Press. p. 5.

- Lovejoy, Paul E. (2003). Trans-Atlantic Dimensions of Ethnicity in the African Diaspora. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-8264-4907-8.

- Isichei, Elizabeth Allo (2002). Voices of the Poor in Africa. Boydell & Brewer. p. 81.

- Rucker, Walter C. (2006). The River Flows on: Black Resistance, Culture, and Identity Formation in Early America. LSU Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8071-3109-1.

- Holloway, Joseph E. (2005). Africanisms in American Culture. bottom of 3rd paragraph: Indiana University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-253-21749-3. Retrieved 2008-12-19.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Philips, John Edward (2005). Writing African History. Boydell & Brewer. p. 412. ISBN 978-1-58046-164-1.

- Berlin, Ira. "African Immigration to Colonial America". History Now. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19.

(paragraph 11) Preferences on both side of the Atlantic determined, to a considerable degree, which enslaved Africans went where and when, populating the mainland with unique combinations of African peoples and creating distinctive regional variations in the Americas.

- Morgan, Philip D.; Sean Hawkins (2004). Black Experience and the Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-926029-4.

- "Ethnic Identity in the Diaspora and the Nigerian Hinterland". Toronto, Canada: York university. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

As is now widely known, enslaved Africans were often concentrated in specific places in the diaspora...USA (Igbo)

- Appiah, Anthony; Henry Louis Gates (1999-10-27). Africana. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-465-00071-5.

- Craton, Michael (1979). Roots and Branches. University of Waterloo Dept. of History. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-08-025367-1.

- McWhorter, John H. (2005). Defining Creole. Oxford University Press US. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-19-516670-5. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- Robotham, Don (January 13, 2008). "Jamaica and Africa (Part II)". Gleaner Company. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

...It is not possible to declare that the Eastern Nigerian influence in Jamaica – apparent in expressions such as 'red ibo' – is Igbo.

- Allsopp, Richard; Jeannette Allsopp (2003). Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Contributor Richard Allsopp. University of the West Indies Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-976-640-145-0.

- Carrington, Sean (2007). A~Z of Barbados Heritage. Macmillan Caribbean Publishers Limited. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-333-92068-8.

- Gibbs, Archibald Robertson (1883). British Honduras: an historical and descriptive account of the colony from its settlement, 1670. S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

Eboe Town, a section of the town of Belize reserved for that African tribe, was destroyed by fire

- Fischer, David Hackett; Kelly, James C. (2000). Bound Away: Virginia and the Westward Movement. University of Virginia Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8139-1774-0.

- Opie, Frederick Douglass (2008). Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America. Columbia University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-231-14638-8.

- "list of languages #25 along with Kru and Yoruba" (PDF). U.S. ENGLISH Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- Ekechi, Felix K. (1972). Missionary Enterprise and Rivalry in Igboland, 1857–1914 (illustrated ed.). last paragraph on page 146: by Routledge. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7146-2778-6.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Chuku, Gloria (2005). Igbo Women and Economic Transformation in Southeastern Nigeria, 1900–1960: 1900–1960 (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-415-97210-9.

- Afigbo, A. E. (1992). Groundwork of Igbo history. Lagos: Vista Books. pp. 522–541. ISBN 978-978-134-400-8.

- Furniss, Graham; Elizabeth Gunner; Liz Gunner (1995). Power, Marginality and African Oral Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-48061-1.

- Ilogu, Edmund (1974). Christianity and Ibo Culture. Brill Archive. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-04-04021-2.

- Sanday, Peggy Reeves (1981). Female Power and Male Dominance: On the Origins of Sexual Inequality (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-521-28075-4.

- Gordon, April A. (2003). Nigeria's Diverse Peoples. ABC-CLIO. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-57607-682-8. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Rubin, Neville (1970). Annual Survey of African Law. Routledge, 1970. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7146-2601-7.

- Fielding, Steven; John W. Young (2003). The Labour Governments 1964–1970: International Policy. Manchester University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7190-4365-9.

- Mathews, Martin P. (2002). Nigeria: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-59033-316-7.

- Minogue, Martin; Judith Molloy (1974). African Aims & Attitudes: Selected Documents. General C. O. Ojukwu: CUP Archive. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-521-20426-2.

- Bocquené, Henri; Oumarou Ndoudi; Gordeen Gorder (2002). Memoirs of a Mbororo: The Life of Ndudi Umaru, Fulani Nomad of Cameroon. Berghahn Books. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-57181-844-7.

- Diamond, Stanley (June 1967). "The Biafra Secession". Africa Today. 14 (3): 1–2. JSTOR 4184781.

- Keil, Charles (January 1970). "The Price of Nigerian Victory". Africa Today. 17 (1): 1–3. JSTOR 4185054.

- "The Igbo, sometimes (especially formerly) referred to as Ibo, are one of the largest single ethnicities in Africa". www.faculty.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "John Lennon". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame + Museum. 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

September 1, 1969: John Lennon returns his MBE. He says it is to protest the British government's involvement in Biafra, its support of the U.S. in Vietnam and the poor chart performance of his latest single, 'Cold Turkey'.

- "Call for Biafra to leave Nigeria". BBC. 6 July 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Ihemere, Kelechukwu U. (2007). A Tri-Generational Study of Language Choice & Shift in Port Harcourt. Universal-Publishers. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-58112-958-8.

- Emenanjọ, Nọlue (1985). Auxiliaries in Igbo Syntax: A Comparative Study. Indiana University Linguistics Club. p. 64.

- Howard-Hassmann, Rhoda E. (1986). Human Rights in Commonwealth Africa. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8476-7433-6. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- Udogu, Emmanuel Ike (2005). Nigeria in the Twenty-first Century: Strategies for Political Stability and Peaceful Coexistence. Africa World Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-59221-320-7. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- Nwachuku, Levi Akalazu (2004). Troubled Journey: Nigeria Since the Civil War. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7618-2712-2. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- Groundwork of Igbo history. Vista Books, Lagos. 1992. pp. 161–177. ISBN 978-978-134-400-8.

- Amadiume, Ifi (2000). The Politics of Memory: Truth, Healing and Social Justice. Zed Books. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-1-85649-843-2.

- Odi, Amusi. "Igbo in Diaspora: The Binding Force of Information" (PDF). University of Texas. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- online catalogue

- Bah, Abu Bakarr (2005). Breakdown and reconstitution: democracy, the nation-state, and ethnicity in Nigeria. Lexington Books. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-7391-0954-0.

- Uwazie, Ernest E.; Albert, Isaac Olawale (1999). Inter-ethnic and religious conflict resolution in Nigeria. Lexington Books. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-7391-0033-2.

- Nwogu, Nneoma V. (2007). Shaping truth, reshaping justice: sectarian politics and the Nigerian truth commission. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2249-5.

- Parijs, Philippe van (2004). Cultural Diversity Versus Economic Solidarity. De Boeck Université. p. 122. ISBN 978-2-8041-4660-3.

- Agbu, Osita (2004). Ethnic militias and the threat to democracy in post-transition Nigeria. Nordic Africa Institute. p. 23. ISBN 978-91-7106-525-4.

- Obichere, Boniface I. (1982). Studies in Southern Nigerian history. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7146-3106-6.

- Smith, Daniel Jordan (2006). A culture of corruption: everyday deception and popular discontent in Nigeria. Princeton University Press. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-691-12722-4.

- Adekson, Adedayo Oluwakayode (2004). The "civil society" problematique: deconstructing civility and southern Nigeria's ethnic radicalization. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-415-94785-5.

- "Nigeria vows to shut down Radio Biafra". BBC News. July 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- "Nigeria Blocks Radio Biafra Station Aimed at Breakaway State". The New York Times. July 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- "Nigerian pirate Radio Biafra returns". BBC News. August 28, 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- Gikandi, Simon (2003). Encyclopedia of African literature. Taylor & Francis. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-415-23019-3.

- Zabus, Chantal (2007). The African palimpsest: indigenization of language in the West African europhone novel. Rodopi. p. 33. ISBN 978-90-420-2224-9.

- "Discomfort of fashion". Antique images and videos of Alaigbo/Ala Igbo (Igboland) posted at Ukpuru blog. 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

Photograph of dancer wearing anklets – Thomas Whitridge Northcote (pre 1913)

- "Willing Submission to Life Sentence to the Stocks". Antique images and videos of Alaigbo/Ala Igbo (Igboland) posted at Ukpuru blog. 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

Photograph of female sitting wearing anklets – Thomas Whitridge Northcote (pre 1913)

- "Nsibidi". National Museum of African Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

Nsibidi is an ancient system of graphic communication indigenous to the Ejagham peoples of southeastern Nigeria and the southwestern Cameroon in the Cross River region. It is also used by neighboring Ibibio, Efik and Igbo peoples.

- Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co. pp. 17, 13. ISBN 978-978-160-264-1.

- "igboenglish". igboenglish. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co. p. 35. ISBN 978-978-160-264-1.

- Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co. p. 21. ISBN 978-978-160-264-1.

- Equiano, Olaudah (1789). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. I. Knapp. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4250-4524-1.

- Oldendorp, Christian Georg Andreas (1777). Geschichte der Mission der evangelischen Brüder auf den caraibischen Inseln ... - Christian Georg Andreas Oldendorp, Johann Jakob Bossart – Google Boeken. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- Achebe, Chinua (1994). Things fall apart. Anchor. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-385-47454-2.

- Grove, George; Stanley Sadie (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (6 ed.). Macmillan Publishers. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Falola, Toyin (2001). Culture and Customs of Nigeria. Greenwood Press. pp. 174–183. ISBN 978-0-313-31338-7.

- Picton, John (2008). "art, African". West Africa, Igbo: Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Eltis, David; David Richardson (1997). Routes to Slavery: Direction, Ethnicity, and Mortality in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7146-4820-0. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- Harper, Peggy (2008). "African dance". 18th paragraph under 'Dance style': Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2009-01-12.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Chuku, Gloria (2005). Igbo women and economic transformation in southeastern Nigeria, 1900–1960. Routledge. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-415-97210-9.

- Gikandi, Simon (1991). Reading Chinua Achebe: Language & Ideology in Fiction. James Currey Publishers. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-85255-527-9. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Oliver, Paul (2008). "African architecture". Geographic influences, Palaces and shrines, last paragraph: Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- "The Poetics of Line". National Museum of African Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Basden, G. S. (1966). Among the Ibos of Nigeria, 1912. Psychology Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-7146-1633-8.

- Greenaway, Theresa; Rolf E. Johnson; Nathan E. Kraucunas (2002). Rain Forests of the World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7614-7254-4.

- Okeke, Chukwuma O.; Ibenwa, Christopher N.; Okeke, Gloria Tochukwu (2017-04-01). "Conflicts Between African Traditional Religion and Christianity in Eastern Nigeria: The Igbo Example". SAGE Open. 7 (2): 2158244017709322. doi:10.1177/2158244017709322. ISSN 2158-2440.

- Ekwueme, Lazarus Nnanyelu (1973). "African Music in Christian Liturgy: The Igbo Experiment". African Music. 5 (3): 12–33. doi:10.21504/amj.v5i3.1655. ISSN 0065-4019. JSTOR 30249968.

- Njemanze PC. Igbo Mediators of Yahweh Culture of Life. London: Xlibris, 2015

- Onwuejeogwu, M. Angulu (1975). The Social Anthropology of Africa: An Introduction (illustrated ed.). Heinemann. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-435-89701-7.

- Basden, G.T.; John Ralph Willis (1912). Among the Ibos of Nigeria. Seeley, Service. p. 216.

- Elechi, O. Oko (2006). Doing Justice Without the State: The Afikpo (Ehugbo) Nigeria Model. CRC Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-415-97729-6.

- Sucher, Sandra J (2007). The Moral Leader: Challenges, Tools and Insights. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-415-40064-0.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1986). Island Societies: Archaeological Approaches to Evolution and Transformation (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-521-30189-3.

- Newell, William Hare (1976). "Ancestoride! Are African Ancestors Dead?". Ancestors. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 293–294. ISBN 978-90-279-7859-2.

- Oluikpe, Benson Omenihu A. (1979). Igbo Transformational Syntax: The Ngwa Dialect Example. Africana Publishers. p. 182.

- Njoku, John E. Eberegbulam (1990). The Igbos of Nigeria: Ancient Rites, Changes, and Survival. E. Mellen Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-88946-173-4.

- Equiano, Olaudah (1837). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. I. Knapp. p. 24.

- Chigere, Nkem Hyginus M. V. (2001). Foreign Missionary Background and Indigenous Evangelization in Igboland. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-8258-4964-1. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- Agbasiere, Joseph Thérèse (2000). Women in Igbo Life and Thought. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-415-22703-2. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- Agbasiere, Joseph Thérèse; Shirley Ardener (2000). Women in Igbo Life and Thought. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-415-22703-2. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- Widjaja, Michael. "igboguide.org". igboguide.org. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- Ritzer, George (2004). Handbook of Social Problems: A Comparative International Perspective. Contributor George Ritzer. SAGE. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7619-2610-8. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- OKONJO, KAMENE (1992). "Aspects of Continuity and Change in Mate-Selection Among the Igbo West of the River Niger". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 23 (3): 339–360. ISSN 0047-2328. JSTOR 41602232.

- Uchendu, Patrick Kenechukwu (1995). Education and the Changing Economic Role of Nigerian Women. Fourth Dimension Publishing. p. 114. ISBN 978-978-156-403-1.

Formerly, there were many polygamous marriages because of the need for many hands to work in the farm.

- Okeke-Ihejirika, Philomina Ezeagbor (2004). Negotiating Power and Privilege: Igbo Career Women in Contemporary Nigeria. Ohio University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-89680-241-4. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- Oheneba-Sakyi, Yaw (2006). African families at the turn of the 21st century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-275-97274-5.

- "THE IGBO TRADITIONAL ATTIRE". thevoicesa.com. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- Chuku, Gloria (2005). Igbo Women and Economic Transformation in Southeastern Nigeria, 1900–1960: 1900–1960. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-415-97210-9. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- Masquelier, Adeline Marie (2005). Dirt, Undress, and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Indiana University Press. pp. 38–45. ISBN 978-0-253-34628-5. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- Equiano, Olaudah (1837). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. I. Knapp. p. 14.

- Ukwu, Dele C. "Igbo People: Clothing & Cosmetic Makeup at the Time of Things Fall Apart". last paragraph. Archived from the original on 2008-09-23. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Isichei, Elizabeth Allo (1977). Igbo Worlds: An Anthology of Oral Histories and Historical Descriptions. Macmillan. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-333-19836-0. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- McCall, John Christensen (2000). Dancing histories: heuristic ethnography with the Ohafia Igbo. University of Michigan Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-472-11070-4.

- Emenanjọ, E. Nọlue (1978). Elements of modern Igbo grammar: a descriptive approach. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-978-154-078-3.

- BBC. "Yam and the Igbos". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- "Igbo | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- Glasgow, Jacqueline; Linda J. Rice (2007). Exploring African Life and Literature: Novel Guides to Promote Socially Responsive Learning. International Reading Assoc. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-87207-609-9. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- McWhorter, John H. (2000). The Missing Spanish Creoles: Recovering the Birth of Plantation Contact Languages. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-520-21999-1. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- O'Halloran, Kate (1997). Hands-on Culture of West Africa. Walch Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8251-3087-8.

- Blacking, John; Joann W. Kealiinohomoku (1979). The Performing Arts: Music and Dance. 4th paragraph: Walter de Gruyter. p. 265. ISBN 978-90-279-7870-7. Retrieved 2009-01-10.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Uchem, Rose N. (2001). Overcoming Women's Subordination in the Igbo African Culture and in the Catholic Church: Envisioning an Inclusive Theology with Reference to Women. Universal-Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-58112-133-9.

- Williams, Lizzie (2008). Nigeria: The Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-84162-239-2.

- Nwachuku, Levi Akalazu; G. N. Uzoigwe (2004). Troubled Journey: Nigeria Since the Civil War. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7618-2712-2. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- Onuah, Felix (29 December 2006). "Nigeria gives census result, avoids risky details". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Lewis, Peter (2007). Growing Apart: Oil, Politics, and Economic Change in Indonesia and Nigeria. University of Michigan Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-472-06980-4. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Suberu, Rotimi T. (2001). Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria. US Institute of Peace Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-929223-28-2. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- IITA Annual Report. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. 1988. p. 8. ISBN 978-978-131-048-5. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Jarmon, Charles (1988). Nigeria. BRILL. p. 113. ISBN 978-90-04-08340-0. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Udeani, Chibueze (2007). Inculturation as Dialogue: Igbo Culture and the Message of Christ. Rodopi. p. 7. ISBN 978-90-420-2229-4.

- Taylor, William H. (1996). Mission to Educate: A History of the Educational Work of the Scottish Presbyterian Mission in East Nigeria, 1846–1960. BRILL. p. 31. ISBN 978-90-04-10713-7. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Pojmann, Wendy Ann (2006). Immigrant Women and Feminism in Italy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-7546-4674-7.

- "World Igbo Environmental Federation" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Falola, Toyin; Niyi Afolabi (2008). Trans-Atlantic Migration: The Paradoxes of Exile. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-415-96091-5.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2004). Africa Is In A Mess What Went Wrong And What Should Be Done. Fultus Corporation. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-9744339-7-4.

- Ciment, James (2001). Encyclopedia of American Immigration. M.E. Sharpe. p. 1075. ISBN 978-0-7656-8028-0.

- Farr, Marcia (2004). Ethnolinguistic Chicago: Language and Literacy in the City's Neighborhoods. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8058-4345-3.

- Dresser, Norine (2005). Multicultural Manners: Essential Rules of Etiquette for the 21st Century (revised, illustrated ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-471-68428-2.

- Eades, Jeremy Seymour (1993). Strangers and Traders: Yoruba Migrants, Markets and the State in Northern Ghana (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh University Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7486-0386-2.

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-313-32384-3.

- Richard, Dreux (July 19, 2011). "Japan's Nigerians pay price for prosperity". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2012-03-31.

- Richard, Dreux (June 11, 2013). "Japan's Nigerians see symbol of change in masquerade". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- "Migration and business: Weaving the world together". The Economist. 2011-11-19. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- "Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories". bottom: Statistics Canada. 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2010-04-04.. 19,520 identify as Nigerian, 61,430 identify as black.

- Crews, Chip (February 1, 2006). "'Lives' Makes a Present of Black Americans' Past". The Washington Post Company. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- James Lipton (Himself – Host), Forest Whitaker (Himself) (2006-12-11). "Inside the Actors Studio: Forest Whitaker (2006)". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 13. New York City, New York, USA. Bravomedia. Bravotv.

- Garner, Jack (October 10, 2006). "Movies: Forest Whitaker takes viewer inside Idi Amin". Gannett News Service. ninth paragraph. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

I wanted to understand what it was like to be Ugandan, even though my roots are in Nigeria and other parts of West Africa.

- Underwood, Blair. "Testimonials". Africanancestry.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

A welcome surprise that my people are from Nigeria & Ibo people

Further reading

|

General

Art

Music

Economy

|

Politics

Society

Diaspora

|

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Igbo people. |