Ahmad al-Mansur

Ahmad al-Mansur (Arabic: أبو العباس أحمد المنصور, Ahmad Abu al-Abbas al-Mansur, also El-Mansour Eddahbi [the Golden], Arabic: أحمد المنصور الذهبي; and Ahmed el-Mansour; 1549 in Fes[1] – 25 August 1603, outskirts of Fes[2][3]) was Sultan of the Saadi dynasty from 1578 to his death in 1603, the sixth and most famous of all rulers of the Saadis. Ahmad al-Mansur was an important figure in both Europe and Africa in the sixteenth century; his powerful army and strategic location made him an important power player in the late Renaissance period. He has been described as "a man of profound Islamic learning, a lover of books, calligraphy and mathematics, as well as a connoisseur of mystical texts and a lover of scholarly discussions."[4]

| Ahmad Abu al-Abbas al-Mansur | |

|---|---|

| Amir al-Muminin | |

| |

| Reign | 1578–1603 |

| Coronation | 1578 |

| Predecessor | Abd al-Malik |

| Successor | Zidan Abu Maali (in Marrakesh) Abou Fares Abdallah (in Fes) |

| Born | 1549 Fes, Morocco |

| Died | 25 August 1603 Outskirts of Fes, Morocco |

| Issue | Zidan Abu Maali Abou Fares Abdallah |

| Dynasty | Saadi |

| Religion | Islam |

Early life

Ahmad was the fifth son of Mohammed ash-Sheikh who was the first Saadi sultan of Morocco. His mother was the well-known Lalla Masuda. After the murder of their father, Mohammed in 1557 and the following struggle for power, the two brothers Ahmad al-Mansur and Abd al-Malik had to flee their elder brother Abdallah al-Ghalib (1557–1574), leave Morocco and stay abroad until 1576. The two brothers spent 17 years among the Ottomans between the Regency of Algiers and Constantinople, and benefited from Ottoman training and contacts with Ottoman culture.[5] More generally, he "received an extensive education in Islamic religious and secular sciences, including theology, law, poetry, grammar, lexicography, exegesis, geometry, arithmetics and algebra, and astronomy."[6]

Battle of Ksar el Kebir

In 1578, Ahmad's brother, Sultan Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik I Saadi, died in battle against the Portuguese army at Ksar-el-Kebir. Ahmad was named his brother's successor and began his reign amid newly won prestige and wealth from the ransom of Portuguese captives.

Rule (1578–1603)

Al-Mansur began his reign by leveraging his dominant position with the vanquished Portuguese during prisoner ransom talks, the collection of which filled the Moroccan royal coffers. Shortly after, he began construction on the great architectural symbol of this new birth of Moroccan power and relevance; the grand palace in Marrakesh called El Badi, or "the marvelous" (El Badi Palace).

Eventually the coffers began to run dry due to the great expense of supporting the military, extensive spy services, the palace and other urban building projects, a royal lifestyle and a propaganda campaign aimed at building support for his controversial claim to the Caliphate.[7]

Relations with Europe

Morocco's standing with the Christian states was still in flux. The Spaniards and the Portuguese were still popularly seen as the infidel, but al-Mansur knew that the only way his Sultanate would thrive was to continue to benefit from alliances with the Christian economies. To do that Morocco had to control sizable gold resources of its own. Accordingly, al-Mansur was drawn irresistibly to the trans-Saharan gold trade of the Songhai in hopes of solving Morocco's economic deficit with Europe.

Ahmad al-Mansur developed friendly relations with England in view of an Anglo-Moroccan alliance. In 1600 he sent his Secretary Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud as ambassador to the Court of Queen Elizabeth I of England to negotiate an alliance against Spain. Ahmad al-Mansur also wrote about reconquering Al-Andalus for Islam back from the Christian Spanish.[8] In a letter of 1 May 1601 he wrote that he also had ambitions to colonize the New World with Moroccans.[8] He envisioned that Islam would prevail in the Americas and the Mahdi would be proclaimed from the two sides of the oceans.[8]

Ahmad al-Mansur had French physicians at his Court. Arnoult de Lisle was physician to the Sultan from 1588 to 1598. He was then succeeded by Étienne Hubert d'Orléans from 1598 to 1600. Both in turn returned to France to become professors of Arabic at the Collège de France, and continued with diplomatic endeavours.[9]

Songhai campaign

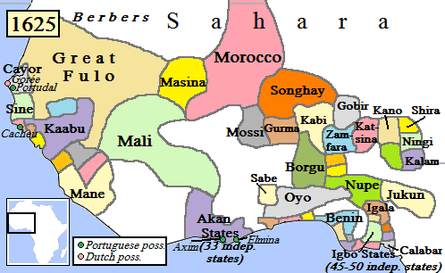

The Songhai Empire was a western African state centered in eastern Mali. From the early 15th to the late 16th century, it was one of the largest African empires in history. On October 16, 1590, Ahmad took advantage of recent civil strife in the empire and dispatched an army of 4,000 men across the Sahara desert under the command of converted Spaniard Judar Pasha.[10] Though the Songhai met them at the Battle of Tondibi with a force of 40,000, they lacked the Moroccan's gunpowder weapons and quickly fled. Ahmad advanced, sacking the Songhai cities of Timbuktu and Djenné, as well as the capital Gao. Despite these initial successes, the logistics of controlling a territory across the Sahara soon grew too difficult, and the Saadians lost control of the cities not long after 1620.[10]

Legacy

Ahmad al-Mansur died of the plague in 1603 and was succeeded by Zidan Abu Maali, who was based in Marrakech, and by Abou Fares Abdallah, who was based in Fes who had only local power. He was buried in the mausoleum of the Saadian Tombs in Marrakech. Well-known writers at his court were Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari, Abd al-Aziz al-Fishtali, Ahmad Ibn al-Qadi and Al-Masfiwi.

Through astute diplomacy al-Mansur resisted the demands of the Ottoman sultan, to preserve Moroccan independence. By playing the Europeans and Ottomans against one another al-Mansur excelled in the art of balance of power diplomacy. Eventually he spent far more than he collected. He attempted to expand his holdings through conquest, and although initially successful in their military campaign against the Songhay Empire, the Moroccans found it increasingly difficult to maintain control over the conquered locals as time went on. Meanwhile, as the Moroccans continued to struggle in the Songhay, their power and prestige on the world stage declined significantly.[7]

Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur was one of the first authorities to take action on smoking in 1602, towards the end of his reign. The ruler of the Saadi dynasty used the religious tool of fatwas (Islamic legal pronouncements) to discourage the use of tobacco.[11][12]

Popular culture

- Featured as the playable leader of the Moroccan civilization in the computer strategy game Civilization V: Brave New World

References

- Rake, Alan (1994). 100 great Africans. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-8108-2929-0.

- Barroll, J. Leeds. Shakespeare studies. Columbia, S.C. [etc.] University of South Carolina Press [etc.] p. 121. ISBN 0-8386-3999-2.

- García-Arenal, Mercedes. Ahmad al-Mansur (Makers of the Muslim World). Oneworld Publications. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-85168-610-0.

- García-Arenal, Mercedes. Ahmad al-Mansur (Makers of the Muslim World). Oneworld Publications. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-85168-610-0.

- Bagley, Frank Ronald Charles; Kissling, Hans Joachim. The last great Muslim empires: history of the Muslim world. p. 103ff.

- García-Arenal, Mercedes. Ahmad al-Mansur (Makers of the Muslim World). Oneworld Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-85168-610-0.

- Smith 2006

- MacLean, Gerald; Nabil Matar (2011). Britain and the Islamic World: 1558-1713.

- Toomer, G. J. Eastern wisedome and learning: the study of Arabic in seventeenth-century England. p. 28ff.

- Kaba, Lansiné (1981), "Archers, musketeers, and mosquitoes: The Moroccan invasion of the Sudan and the Songhay resistance (1591–1612)", Journal of African History, 22: 457–475, doi:10.1017/S0021853700019861, JSTOR 181298, PMID 11632225.

- Khayat, M.H., ed. (2000). Islamic Ruling on Smoking (PDF) (2 ed.). Alexandria, Egypt: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. ISBN 978-92-9021-277-5.

- "How tobacco firms try to undermine Muslim countries' smoking ban". The Daily Observer. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

Bibliography

- Davidson, Basil (1995), Africa in history : themes and outlines, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-82667-4.

- Mouline, Nabil (2009), Le califat imaginaire d'Ahmad al-Mansûr, Presses Universitaires de France.

- Smith, Richard L. (2006), Ahmad al-Mansur: Islamic Visionary, New York: Pearson Longman, ISBN 0-321-25044-3.

| Preceded by Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik I |

Sultan of Morocco 1578–1603 |

Succeeded by Zidan al-Nasir |