Thomas Sankara

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (French pronunciation: [tɔma sɑ̃kaʁa]; 21 December 1949 – 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabé militant social justice campaigner and President of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987. A Marxist–Leninist and pan-Africanist, he was viewed by supporters as a charismatic and iconic figure of revolution and is sometimes referred to as "Africa's Che Guevara".[1][2][3][4]

Thomas Sankara | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of Burkina Faso | |

| In office 4 August 1983 – 15 October 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo |

| Succeeded by | Blaise Compaoré (coup d'état) |

| 5th Prime Minister of Upper Volta | |

| In office 10 January 1983 – 17 May 1983 | |

| President | Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo |

| Preceded by | Saye Zerbo |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished |

| Secretary of State for Information | |

| In office 9 September 1981 – 21 April 1982 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara 21 December 1949 Yako, Upper Volta |

| Died | 15 October 1987 (aged 37) Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Resting place | Ouagadougou |

| Spouse(s) | Mariam Sankara |

| Children | 2 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Battles/wars | Agacher Strip War |

After being appointed Prime Minister in 1983, disputes with the sitting government led to Sankara's eventual imprisonment. While he was under house arrest, a group of revolutionaries seized power on his behalf in a popularly-supported coup later that year. Aged 33, Sankara became the President of the Republic of Upper Volta. He immediately launched programmes for social, ecological and economic change and renamed the country from the French colonial name Upper Volta to Burkina Faso ("Land of Incorruptible People"), with its people being called Burkinabé ("upright people").[5][6] His foreign policies were centred on anti-imperialism, with his government eschewing all foreign aid, pushing for odious debt reduction, nationalising all land and mineral wealth and averting the power and influence of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. His domestic policies were focused on preventing famine with agrarian self-sufficiency and land reform, prioritising education with a nationwide literacy campaign and promoting public health by vaccinating 2.5 million children against meningitis, yellow fever and measles.[7]

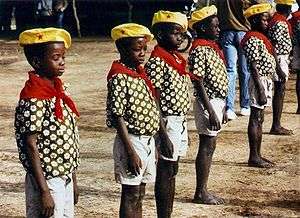

Other components of his national agenda included planting over 10 million trees to combat the growing desertification of the Sahel, redistributing land from feudal landlords to peasants, suspending rural poll taxes and domestic rents and establishing a road and railway construction programme.[8] On the local level, Sankara called on every village to build a medical dispensary and had over 350 communities build schools with their own labour. Moreover, he outlawed female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy. He appointed women to high governmental positions and encouraged them to work outside the home and stay in school, even if pregnant.[8] Sankara encouraged the prosecution of officials accused of corruption, counter-revolutionaries and "lazy workers" in Popular Revolutionary Tribunals.[8] As an admirer of the Cuban Revolution, Sankara set up Cuban-style Committees for the Defense of the Revolution.[1]

His revolutionary programmes for African self-reliance made him an icon to many of Africa's poor.[8] Sankara remained popular with most of his country's citizens. However, his policies alienated and antagonised several groups, which included the small but powerful Burkinabé middle class; the tribal leaders who were stripped of their long-held traditional privileges of forced labour and tribute payments; and the governments of France and its ally the Ivory Coast.[1][9] On 15 October 1987, Sankara was assassinated by troops led by Blaise Compaoré, who assumed leadership of the state shortly after having Sankara killed. A week before his assassination, Sankara declared: "While revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas".[1]

Early life

Thomas Sankara was born Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara[10] on 21 December 1949 in Yako, French Upper Volta as the third of ten children to Joseph and Marguerite Sankara. His father, Joseph Sankara, a gendarme,[11][12] was of mixed Mossi–Fulani (Silmi–Moaga) heritage while his mother, Marguerite Kinda, was of direct Mossi descent.[13] He spent his early years in Gaoua, a town in the humid southwest to which his father was transferred as an auxiliary gendarme. As the son of one of the few African functionaries then employed by the colonial state, he enjoyed a relatively privileged position. The family lived in a brick house with the families of other gendarmes at the top of a hill overlooking the rest of Gaoua.[10]

Sankara attended primary school at Bobo-Dioulasso. He applied himself seriously to his schoolwork and excelled in mathematics and French. He went to church often, and impressed with his energy and eagerness to learn, some of the priests encouraged Thomas to go on to seminary school once he finished primary school. Despite initially agreeing, he took the exam required for entry to the sixth grade in the secular educational system and passed. Thomas's decision to continue his education at the nearest lycée Ouezzin Coulibaly (named after a preindependence nationalist) proved to be a turning point. This step got him out of his father's household since the lycée was in Bobo-Dioulasso, the country's commercial centre. At the lycée, Sankara made close friends, including Fidèle Too, whom he later named a minister in his government; and Soumane Touré, who was in a more advanced class.[10]

His Roman Catholic parents wanted him to become a priest, but he chose to enter the military. The military was popular at the time, having just ousted a despised president. It was also seen by young intellectuals as a national institution that might potentially help to discipline the inefficient and corrupt bureaucracy, counterbalance the inordinate influence of traditional chiefs and generally help modernize the country. Besides, acceptance into the military academy would come with a scholarship; Sankara could not easily afford the costs of further education otherwise. He took the entrance exam and passed.[10][14]

He entered the military academy of Kadiogo in Ouagadougou with the academy's first intake of 1966 at the age of 17.[10] While there he witnessed the first military coup d'état in Upper Volta led by Lieutenant-Colonel Sangoulé Lamizana (3 January 1966). The trainee officers were taught by civilian professors in the social sciences. Adama Touré, who taught history and geography and was known for having progressive ideas, even though he did not publicly share them, was the academic director at the time. He invited a few of his brightest and more political students, among them Sankara, to join informal discussions about imperialism, neocolonialism, socialism and communism, the Soviet and Chinese revolutions, the liberation movements in Africa and similar topics outside of the classroom. This was the first time Sankara was systematically exposed to a revolutionary perspective on Upper Volta and the world. Aside from his academic and extracurricular political activities, Sankara also pursued his passion for music and played the guitar.[10]

In 1970, 20 year old Sankara went on for further military studies at the military academy of Antsirabe (Madagascar), from which he graduated as a junior officer in 1973. At the Antsirabe academy, the range of instruction went beyond standard military subjects, which allowed Sankara to study agriculture, including how to raise crop yields and better the lives of farmers—themes he later took up in his own administration and country.[10] During that period, he read profusely on history and military strategy, thus acquiring the concepts and analytical tools that he would later use in his reinterpretation of Burkinabe political history.[15]

Military career

After basic military training in secondary school in 1966, Sankara began his military career at the age of 19 and a year later was sent to Madagascar for officer training at Antsirabe where he witnessed popular uprisings in 1971 and 1972 against the government of Philibert Tsiranana and first read the works of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, profoundly influencing his political views for the rest of his life.[16]

Returning to Upper Volta in 1972, he fought in a border war between Upper Volta and Mali by 1974. He earned fame for his heroic performance in the border war with Mali, but years later would renounce the war as "useless and unjust", a reflection of his growing political consciousness.[17] He also became a popular figure in the capital of Ouagadougou. Sankara was a decent guitarist. He played in a band named "Tout-à-Coup Jazz" and rode a motorcycle.

In 1976 he became commander of the Commando Training Centre in Pô. In the same year he met Blaise Compaoré in Morocco. During the presidency of Colonel Saye Zerbo, a group of young officers formed a secret organisation called the "Communist Officers' Group" (Regroupement des officiers communistes, or ROC), the best-known members being Henri Zongo, Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani, Blaise Compaoré and Sankara.

Government posts

Sankara was appointed Minister of Information in Saye Zerbo's military government in September 1981.[10] Sankara differentiated himself from other government officials in many ways such as biking to work everyday, instead of driving in a car. While his predecessors would censor journalists and newspapers, Sankara encouraged investigative journalism and allowed the media to print whatever it found.[18] This led to publications of government scandals by both privately-owned and state-owned newspapers.[10] He resigned on 12 April 1982 in opposition to what he saw as the regime's anti-labour drift, declaring "Misfortune to those who gag the people!" (Malheur à ceux qui bâillonnent le peuple!).[10]

After another coup (7 November 1982) brought to power Major-Doctor Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo, Sankara became Prime Minister in January 1983 but he was dismissed (17 May). In between those four months, Sankara pushed Ouédraogo's regime for more progressive reforms.[19] Sankara was then arrested after the French President's African affairs adviser, Guy Penne, met with Col. Yorian Somé.[20] Henri Zongo and Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lingani were also placed under arrest. The decision to arrest Sankara proved to be very unpopular with the younger officers in the military regime and his imprisonment created enough momentum for his friend Blaise Compaoré to lead another coup.[19]

Presidency

A coup d'état organised by Blaise Compaoré made Sankara President on 4 August 1983 at the age of 33. The coup d'état was supported by Libya, which was at the time on the verge of war with France in Chad (see history of Chad).

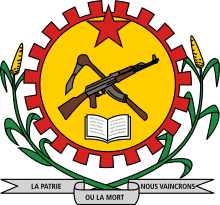

Sankara saw himself as a revolutionary and was inspired by the examples of Cuba's Fidel Castro and Che Guevara and Ghana's military leader Jerry Rawlings. As President, he promoted the "Democratic and Popular Revolution" (Révolution démocratique et populaire, or RDP). The ideology of the Revolution was defined by Sankara as anti-imperialist in a speech of 2 October 1983, the Discours d'orientation politique (DOP), written by his close associate Valère Somé. His policy was oriented toward fighting corruption, promoting reforestation, averting famine and making education and health real priorities.

On the first anniversary of his accession in 1984, he renamed the country Burkina Faso, meaning "the land of upright people" in Moré and Dyula, the two major languages of the country. He also gave it a new flag and wrote a new national anthem (Une Seule Nuit).

Creating self-sufficiency

Immediately after Sankara took office, he suppressed most of the powers held by tribal chiefs in Burkina Faso. These feudal landlords were stripped of their rights to tribute payments and forced labour as well as having their land distributed amongst the peasantry.[21] This served the dual purpose of creating a higher standard of living for the average Burkinabé as well as creating an optimal situation to induce Burkina Faso into food self-sufficiency.[22]

Within four years, Burkina Faso reached food sufficiency due in large part to feudal land redistribution and series of irrigation and fertilization programs instituted by the government. During this time, production of cotton and wheat increased dramatically. While the average wheat production for the Sahel region was 1,700 kilograms per hectare (1,500 lb/acre) in 1986, Burkina Faso was producing 3,900 kilograms per hectare (3,500 lb/acre) of wheat the same year.[22] This success meant Sankara had not only shifted his country into food self-sufficiency, but had in turn created a food surplus.[8] Sankara also emphasized the production of cotton and the need to transform the cotton produced in Burkina Faso into clothing for the people.[23]

Health care and public works

Sankara's first priorities after taking office were feeding, housing and giving medical care to his people who desperately needed it. Sankara launched a mass vaccination program in an attempt to eradicate polio, meningitis and measles. From 1983 to 1985, roughly 2 million Burkinabé were vaccinated.[8][24] Prior to Sankara’s presidency infant mortality in Burkina Faso was about 20.8%, during his presidency it fell to 14.5%.[24] Sankara's administration was also the first African government to publicly recognize the AIDS epidemic as a major threat to Africa.[25]

Large-scale housing and infrastructure projects were also undertaken. Brick factories were created to help build houses in effort to end urban slums.[22] In an attempt to fight deforestation, The People's Harvest of Forest Nurseries was created to supply 7,000 village nurseries, as well as organizing the planting of several million trees. All regions of the country were soon connected by a vast road- and rail-building program. Over 700 km (430 mi) of rail was laid by Burkinabé people to facilitate manganese extraction in "The Battle of the Rails" without any foreign aid or outside money.[8] These programs were an attempt to prove that African countries could be prosperous without foreign help or aid. Sankara also launched education programs to help combat the country's 90% illiteracy rate. These programs had some success in the first few years. However, wide-scale teacher strikes, coupled with Sankara's unwillingness to negotiate, led to the creation of "Revolutionary Teachers". In an attempt to replace the nearly 2,500 teachers fired over a strike in 1987, anyone with a college degree was invited to teach through the revolutionary teachers program. Volunteers merely received a 10-day training course before beginning to teach.[8]

People's Revolutionary Tribunals

Shortly after attaining power, Sankara constructed a system of courts known as the Popular Revolutionary Tribunal. The courts were created originally to try former government officials in a straightforward way so the average Burkinabé could participate in or oversee trials of enemies of the revolution.[8] They placed defendants on trial for corruption, tax evasion or "counter-revolutionary" activity. Sentences for former government officials were light and often suspended. The tribunals have been alleged to have been only show trials,[26] held very openly with oversight from the public.

According to the US State Department procedures in these trials, especially legal protections for the accused, did not conform to international standards. Defendants had to prove themselves innocent of the crimes they were charged with committing and were not allowed to be represented by counsel.[27] The courts were originally met with adoration from the Burkinabé people but over time became corrupt and oppressive. So called "lazy workers" were tried and sentenced to work for free or expelled from their jobs and discriminated against. Some even created their own courts to settle scores and humiliate their enemies.[8]

Revolutionary Defense Committees

The Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (Burkina Faso) (Comités de Défense de la Révolution) were formed as mass armed organizations. The CDRs were created as a counterweight to the power of the army as well as to promote political and social revolution. The idea for the Revolutionary Defense Committees was taken from Fidel Castro, whose Committees for the Defense of the Revolution were created as a form of "revolutionary vigilance".[28]

Sankara's CDRs overstepped their power, and were accused by some of thuggery and gang-like behavior. CDR groups would meddle in the everyday life of the Burkinabé. Individuals would use their power to settle scores or punish enemies. Sankara himself noted the failure publicly. The public placed blame for actions of individual CDRs squarely on Sankara.[8] The failure of the CDRs, coupled with the failure of the Revolutionary Teachers program, mounting labour and middle class disdain as well as Sankara's steadfastness, lead to the regime partially weakening within Burkina Faso.[8]

Relations with the Mossi People

A point of contention regarding Sankara's rule is the way he handled the Mossi ethnic group. The Mossi are the most populous ethnic group in Burkina Faso, and they adhere to strict traditional hierarchical social systems.[29] At the top of the hierarchy is the Morho Naba, the chief or king of the Mossi people. Sankara viewed the institution as an obstacle to national unity, and proceeded to demote the Mossi elites. The Morho Naba was not allowed to hold courts, and local village chiefs were stripped of their executive powers and given to the CDR.[30]

Women's rights

Improving women's status in Burkinabé society was one of Sankara's explicit goals, and his government included a large number of women, an unprecedented policy priority in West Africa. His government banned female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy, while appointing women to high governmental positions and encouraging them to work outside the home and stay in school even if pregnant.[8]

Sankara also promoted contraception and encouraged husbands to go to market and prepare meals to experience for themselves the conditions faced by women. Sankara recognized the challenges faced by African women when he gave his famous address to mark International Women's Day on 8 March 1987 in Ouagadougou. Sankara spoke to thousands of women in a highly political speech in which he stated that the Burkinabé Revolution was "establishing new social relations" which would be "upsetting the relations of authority between men and women and forcing each to rethink the nature of both. This task is formidable but necessary".[31] Furthermore, Sankara was the first African leader to appoint women to major cabinet positions and to recruit them actively for the military.[8]

Second Agacher strip war

In 1985, Burkina Faso organised a general population census. During the census, some Fula camps in Mali were visited by mistake by Burkinabé census agents.[32] The Malian government claimed that the act was a violation of its sovereignty on the Agacher strip. Following efforts by Mali asking African leaders to pressure Sankara,[32] tensions erupted on Christmas Day 1985 in a war that lasted five days and killed about 100 people (most victims were civilians killed by a bomb dropped on the marketplace in Ouahigouya by a Malian MiG plane). The conflict is known as the "Christmas war" in Burkina Faso.

Criticism

Sankara's government was criticised by Amnesty International and other international humanitarian organisations for violations of human rights, including extrajudicial executions and arbitrary detentions of political opponents by the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution.[33] The British development organisation Oxfam recorded the arrest of trade union leaders in 1987.[34] In 1984, seven individuals associated with the previous régime were accused of treason and executed after a summary trial. A teachers' strike the same year resulted in the dismissal of 2,500 teachers; thereafter, non-governmental organisations and unions were harassed or placed under the authority of the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution, branches of which were established in each workplace and which functioned as "organs of political and social control".[35]

Popular Revolutionary Tribunals, set up by the government throughout the country, placed defendants on trial for corruption, tax evasion or "counter-revolutionary" activity. Procedures in these trials, especially legal protections for the accused, did not conform to international standards. According to Christian Morrisson and Jean-Paul Azam of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the "climate of urgency and drastic action in which many punishments were carried out immediately against those who had the misfortune to be found guilty of unrevolutionary behaviour, bore some resemblance to what occurred in the worst days of the French Revolution, during the Reign of Terror. Although few people were killed, violence was widespread".[36] The following chart shows Burkina Faso's human rights ratings under Sankara from 1984–1987 presented in the Freedom in the World reports, published annually by the United States government funded Freedom House. A score of 1 is "most free" and 7 is "least free".[37]1

| Year | Political rights | Civil liberties | Status |

| 1984 | 7 | 5 | Not free |

| 1985 | 7 | 6 | Not free |

| 1986 | 7 | 6 | Not free |

| 1987 | 7 | 6 | Not free |

Personal image and popularity

Accompanying his personal charisma, Sankara had an array of original initiatives that contributed to his popularity and brought some international media attention to his government:

Solidarity

- He sold off the government fleet of Mercedes cars and made the Renault 5 (the cheapest car sold in Burkina Faso at that time) the official service car of the ministers.

- He reduced the salaries of well-off public servants (including his own) and forbade the use of government chauffeurs and first class airline tickets.

- He redistributed land from the feudal landlords to the peasants. Wheat production increased from 1,700 kilograms per hectare (1,500 lb/acre) to 3,800 kilograms per hectare (3,400 lb/acre), making the country food self-sufficient.[8]

- He opposed foreign aid, saying that "he who feeds you, controls you".[8]

- He spoke in forums like the Organization of African Unity against what he described as neo-colonialist penetration of Africa through Western trade and finance.[8]

- He called for a united front of African nations to repudiate their foreign debt. He argued that the poor and exploited did not have an obligation to repay money to the rich and exploiting.[8]

— Mariam Sankara, Thomas' widow[1]

- In Ouagadougou, Sankara converted the army's provisioning store into a state-owned supermarket open to everyone (the first supermarket in the country).[1]

- He forced well-off civil servants to pay one month's salary to public projects.[1]

- He refused to use the air conditioning in his office on the grounds that such luxury was not available to anyone but a handful of Burkinabés.[7]

- As President, he lowered his salary to $450 a month and limited his possessions to a car, four bikes, three guitars, a refrigerator, and a broken freezer.[7]

Style

- He required public servants to wear a traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabé cotton and sewn by Burkinabé craftsmen.[8]

- He was known for jogging unaccompanied through Ouagadougou in his track suit and posing in his tailored military fatigues, with his mother-of-pearl pistol.[1]

- When asked why he did not want his portrait hung in public places, as was the norm for other African leaders, Sankara replied: "There are seven million Thomas Sankaras".[7]

- An accomplished guitarist, he wrote the new national anthem himself.[1]

Africa's Che Guevara

Sankara is often referred to as "Africa's Che Guevara".[1] Sankara gave a speech marking and honouring the 20th anniversary of Che Guevara's 9 October 1967 execution, one week before his own assassination on 15 October 1987.[38]

Assassination

On 15 October 1987, Sankara was killed by an armed group with twelve other officials in a coup d'état organized by his former colleague Blaise Compaoré. When accounting for his overthrow, Compaoré stated that Sankara jeopardized foreign relations with former colonial power France and neighbouring Ivory Coast, and accused his former comrade of plotting to assassinate opponents.[1]

Prince Johnson, a former Liberian warlord allied to Charles Taylor, told Liberia's Truth and Reconciliation Commission that it was engineered by Charles Taylor.[39] After the coup and although Sankara was known to be dead, some CDRs mounted an armed resistance to the army for several days.[40]

According to Halouna Traoré, the sole survivor of Sankara's assassination, Sankara was attending a meeting with the Conseil de l'Entente.[41] His assassins singled out Sankara and executed him, riddling him with bullets to the back. The assassins then shot at those attending the meeting, killing 12 other people. Sankara's body was dismembered and he was quickly buried in an unmarked grave[8] while his widow Mariam and two children fled the nation.[42] Compaoré immediately reversed the nationalizations, overturned nearly all of Sankara's policies, rejoined the International Monetary Fund and World Bank to bring in "desperately needed" funds to restore the "shattered" economy[43] and ultimately spurned most of Sankara's legacy. Compaoré's dictatorship remained in power for 27 years until it was overthrown by popular protests in 2014.

Exhumation

The exhumation of what are believed to be the remains of Sankara was started on African Liberation Day, 25 May 2015. Once exhumed, the family would formally identify the remains, a long-standing demand of his family and supporters. Permission for an exhumation was denied during the rule of his successor, Blaise Compaoré.[44] In October 2015, one of the lawyers for Sankara's widow Mariam reported that the autopsy had revealed that Sankara's body was "riddled" with "more than a dozen" bullets.[45]

Legacy

20 years after his assassination, Sankara was commemorated on 15 October 2007 in ceremonies that took place in Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, Niger, Tanzania, Burundi, France, Canada and the United States.

List of works

- Thomas Sankara Speaks: The Burkina Faso Revolution, 1983–87, Pathfinder Press: 1988. ISBN 0-87348-527-0.

- We Are the Heirs of the World's Revolutions: Speeches from the Burkina Faso Revolution 1983–87, Pathfinder Press: 2007. ISBN 0-87348-989-6.

- Women's Liberation and the African Freedom Struggle, Pathfinder Press: 1990. ISBN 0-87348-585-8.

Further reading

Books

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Sankara |

- Who killed Sankara?, by Alfred Cudjoe, 1988, University of California, ISBN 9964-90-354-5.

- La voce nel deserto, by Vittorio Martinelli and Sofia Massai, 2009, Zona Editrice, ISBN 978-88-6438-001-8.

- Thomas Sankara – An African Revolutionary, by Ernest Harsch, 2014, Ohio University Press, ISBN 978-0-8214-4507-5.

- A Certain Amount of Madness: The Life Politics and Legacies of Thomas Sankara (Black Critique), by Amber Murrey, 2018, Pluto Press, ISBN 978-0-7453-3758-6.

- Sankara, Compaoré et la révolution burkinabè, by Ludo Martens and Hilde Meesters, 1989, Editions Aden, ISBN 9782872620333.

Historical Novel including Thomas Sankara

- American Spy, by Lauren Wilkinson, 2019, Random House, ISBN 978-0812998955.

Web articles

- Burkina Faso's Pure President by Bruno Jaffré.

- Thomas Sankara Lives! by Mukoma Wa Ngugi.

- There Are Seven Million Sankaras by Koni Benson.

- Thomas Sankara: "I have a Dream" by Federico Bastiani.

- Thomas Sankara: Chronicle of an Organised Tragedy by Cheriff M. Sy.

- Thomas Sankara Former Leader of Burkina Faso by Désiré-Joseph Katihabwa.

- Thomas Sankara 20 Years Later: A Tribute to Integrity by Demba Moussa Dembélé.

- Remembering Thomas Sankara, Rebecca Davis, The Daily Maverick, 2013.

- "I can hear the roar of women's silence", Sokarie Ekine, Red Pepper, 2012.

- Thomas Sankara: A View of The Future for Africa and The Third World by Ameth Lo.

- Thomas Sankara on the Emancipation of Women, An internationalist whose ideas live on! by Nathi Mthethwa.

- Thomas Sankara, le Che africain by Pierre Venuat (in French).

- Thomas Sankara e la rivoluzione interrotta by Enrico Palumbo (in Italian).

DVD

- Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man, 2006, directed by Robin Shuffield, (52 min), CreateSpace, ASIN: B002OEBRKC.[46]

References

- Burkina Faso Salutes "Africa's Che" Thomas Sankara by Mathieu Bonkoungou, Reuters, 17 October 2007.

- Thomas Sankara Speaks: the Burkina Faso Revolution: 1983–87, by Thomas Sankara, edited by Michel Prairie; Pathfinder, 2007, pg 11

- "Thomas Sankara, Africa's Che Guevara" by Radio Netherlands Worldwide, 15 October 2007.

- "Africa's Che Guevara" by Sarah in Burkina Faso.

- Hubert, Jules Deschamps. "Burkina Faso". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Molly, John. "What Do the Colors and Symbols of the Flag of Burkina Faso Mean?". World Atlas. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "Commemorating Thomas Sankara" by Farid Omar, Group for Research and Initiative for the Liberation of Africa (GRILA), 28 November 2007.

- "Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man" by California Newsreel.

- "BBC NEWS – Africa – Burkina commemorates slain leader". news.bbc.co.uk. 15 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Harsch, Ernest (1 November 2014). Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary. Ohio University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780821445075.

- "404 Not Found" Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Décès de Joseph sambo père du Président Thomas Sankara - Ouagadougou au Burkina Faso". ouaga-ca-bouge.net. Archived from the original on 17 August 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- Dictionary of African Biography. 6. OUP USA. 2012. p. 268. ISBN 9780195382075.

- Ray, Carina. "Thomas Sankara". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Martin, G. (23 December 2012). African Political Thought. Springer. ISBN 9781137062055.

- Thomas Sankara Speaks: the Burkina Faso Revolution: 1983–87, by Thomas Sankara, edited by Michel Prairie; Pathfinder, 2007, pp. 20–21.

- "The True Visionary Thomas Sankara" Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine by Antonio de Figueiredo, 27 February 2008.

- Brittain, Victoria (3 January 2007). "Introduction to Sankara & Burkina Faso". Review of African Political Economy. 12 (32): 39–47. doi:10.1080/03056248508703613. ISSN 0305-6244.

- Skinner, Elliott P. (1988). "Sankara and the Burkinabe Revolution: Charisma and Power, Local and External Dimensions". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 26 (3): 442–443. doi:10.1017/S0022278X0001171X. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160892.

- Martin, Guy (1987). "Ideology and Praxis in Thomas Sankara's Populist Revolution of 4 August 1983 in Burkina Faso". Issue: A Journal of Opinion. 15: 77–90. doi:10.2307/1166927. ISSN 0047-1607. JSTOR 1166927.

- "Burkina Faso: Upright once again". Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist). 29 October 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "Africa's Che Guevara and Burkina Faso - African Agenda – A new perspective on Africa". africanagenda.net. 9 January 2020.

- "Thomas Sankara: an endogenous approach to development - Pambazuka News". pambazuka.net.

- Zeilig, Leo (2018). A Certain Amount of Madness: The Life, Politics and Legacies of Thomas Sankara. Pluto Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7453-3757-9. JSTOR j.ctt21kk235.

- HIV/AIDS, illness, and African well-being, by Toyin Falola & Matthew M. Heaton, University Rochester Press, 2007, ISBN 1-58046-240-5, p. 290.

- Ciment, James; Hill, Kenneth, eds. (2012). "BURKINA FASO: Coups, 1966–1987". Encyclopedia of Conflicts since World War II. London: Routledge. p. 339. ISBN 978-113-659-621-6.

- State, US Department of (1 February 1987). "Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1986". www.ecoi.net.

- Baggins, Brian. "Establishing Revolutionary Vigilance in Cuba". marxists.org.

- "Mossi | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Wilkins, Michael (1989). "The Death of Thomas Sankara and the Rectification of the People's Revolution in Burkina Faso". African Affairs. 88 (352): 384. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098188. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 722692.

- "Revisiting Thomas Sankara, 26 years later - Pambazuka News". pambazuka.net.

- Bryant, Terry (2007). History's Greatest War. Global Media.

- Amnesty International, Burkina Faso: Political Imprisonment and the Use of Torture from 1983 to 1988 (London: Amnesty International, 1988).

- R. Sharp, Burkina Faso: New Life for the Sahel? A Report for Oxfam (Oxford: Oxfam, 1987), p. 13.

- R. Otayek, 'The Revolutionary Process in Burkina Faso: Breaks and Continuities,' in J. Markakis & M. Waller, eds., Military Marxist Régimes in Africa (London: Frank Cass, 1986), p. 95.

- Morrisson, C.; Azam, J.-P. (1999). Conflict and Growth in Africa. I: 'The Sahel'. Paris: OECD. p. 70.

- "Country ratings and status 1973–2014" (XLS). Freedom in the World. Freedom House. 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Sankara 20 years Later: A Tribute to Integrity Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine by Demba Moussa Dembélé, Pambazuka News, 15 October 2008.

- "US freed Taylor to overthrow Doe, Liberia's TRC hears". The M&G Online. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Ake, Claude (2001). Democracy and Development in Africa. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 95. ISBN 081-572-348-2.

- Jaffre, Bruno (2018). A Certain Amount of Madness: The Life, Politics and Legacies of Thomas Sankara. Pluto Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7453-3757-9. JSTOR j.ctt21kk235.

- Sankara v. Burkina Faso by the Canadian Council on International Law, March 2007

- Mason, Katrina and; Knight, James (2011). Burkina Faso, 2nd. The Globe Pequot Press Inc. p. 31. ISBN 9781841623528.

- "Thomas Sankara remains: Burkina Faso begins exhumation". BBC News. 25 May 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Iaccino, Ludovica (14 October 2015). "Thomas Sankara: Body of Africa's Che Guevara riddled with bullets, autopsy reveals three decades after death". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- DVD review of Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man Archived 2011-02-03 at the Wayback Machine directed by Robin Shuffield.

External links

![]()

![]()

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo |

President of Upper Volta (Burkina Faso) 1983–1987 |

Succeeded by Blaise Compaoré |