Hotak dynasty

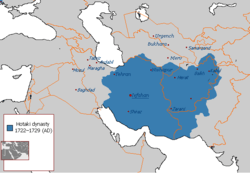

The Hotak dynasty (Pashto: د هوتکيانو ټولواکمني; Persian: سلسلهٔ هوتکیان) was an Afghan monarchy of the Ghilji Pashtuns,[2][3] established in April 1709 by Mirwais Hotak after leading a successful revolution against their declining Persian Safavid overlords in the region of Loy Kandahar ("Greater Kandahar") in what is now southern Afghanistan.[2] It lasted until 1738 when the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, Nader Shah Afshar, defeated Hussain Hotak during the long siege of Kandahar, and started the reestablishment of Iranian suzerainty over all regions lost decades before against the Iranian archrival, the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian Empire.[4] At its peak, the Hotak dynasty ruled briefly over an area which is now Afghanistan, Iran, western Pakistan, and some parts of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

Hotak Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1709–1738 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Hotak Empire at its peak (1722–1729) | |||||||||||

| Capital | Kandahar Isfahan | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Pashto and Persian (poetry)[lower-alpha 1][1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||||

• 1709–1715 | Mirwais Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1715–1717 | Abdul Aziz Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1717–1725 | Mahmud Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1725–1730 | Ashraf Hotak | ||||||||||

• 1725–1738 | Hussain Hotak | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||

| 21 April 1709 | |||||||||||

| 24 March 1738 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

In 1715, Mirwais died of a natural cause and his brother Abdul Aziz succeeded to the monarchy. He was quickly followed by Mahmud who ruled the empire at its largest extent for a mere three years. Following the 1729 Battle of Damghan, where Ashraf Hotak was roundly defeated by Nader Shah, Ashraf was banished to what is now southern Afghanistan with Hotak rule being confined to it. Hussain Hotak became the last ruler until he was also defeated in 1738.

Rise to power

Loy Kandahar was ruled by the Shi'a Safavids as their far easternmost territory from the 16th century until the early 18th century, while the native Afghan tribes living in the area were Sunni Muslims. Immediately to the east began the Sunni Mughul Empire, who occasionally fought wars with the powerful Safavids over the territory of southern Afghanistan.[5] The area to the north, was controlled by the Khanate of Bukhara at the same time.

By the late 17th century, the Iranian Safavids, like their arch rival the Ottoman Turks, had been starting to heavily decline due to misrule, sectarian strife, and foreign interests. In 1704, the Safavid Shah Husayn appointed his Georgian subject and king of Kartli George XI (Gurgīn Khān), who had converted to Islam like many other Georgians under Ottoman or Persian rule, as the commander-in-chief of the easternmost provinces of the Safavid Empire, in what is now Afghanistan.[6] His first task was to quell the uprisings in the region. Gurgin began imprisoning and executing Afghans, especially those suspected of organizing rebellions, successfully crushing the rebellions. One of those arrested and imprisoned was Mirwais who belonged to an influential Hotak family in the Kandahar region. Mirwais was sent as a prisoner to the Persian court in Isfahan but the charges against him were dismissed by Shah Husayn, so he was sent back to his native land as a free man.[7]

In April 1709, Mirwais, protected by the Ghaznavid Nasher Khans,[8] and along with his followers revolted against the Safavid rule at Kandahar. The uprising began when Gurgīn Khān and his escort were killed during a feast that was organized by Mirwais at his farmhouse outside the city. It is reported that drinking of wine was involved. Next, Mirwais ordered the killings of the remaining Persian military officials in the region. The Afghans then defeated a twice as large Persian army that had been dispatched from Isfahan (capital of the Safavids), one which included Qizilbash and Georgian/Circassian troops.[9]

Several half-hearted attempts to subdue the rebellious city having failed, the Persian Government despatched Khusraw Khán, nephew of the late Gurgín Khán, with an army of 30,000 men to effect its subjugation, but in spite of an initial success, which led the Afgháns to offer to surrender on terms, his uncompromising attitude impelled them to make a fresh desperate effort, resulting in the complete defeat of the Persian army (of whom only some 700 escaped) and the death of their general. Two years later, in A.D. 1713, another Persian army commanded by Rustam Khán was also defeated by the rebels, who thus secured possession of the whole Loy Kandahar region.[9]

— Edward G. Browne, 1924

Refusing the title of king, Mirwais was called "Prince of Qandahár and General of the national troops" by his Afghan countrymen. He died peacefully in November 1715 from natural causes and was succeeded by his brother Abdul Aziz; the latter was murdered later by Mirwais' son Mahmud. In 1720, Mahmud's Afghan forces crossed the deserts of Sistan and captured Kerman.[9] His plan was to conquer the Persian capital, Isfahan.[10] After defeating the Persian army at the Battle of Gulnabad on March 8, 1722, he proceeded to and besieged Isfahan for 6 months, after which it fell.[11] On October 23, 1722, Sultan Husayn abdicated and acknowledged Mahmud as the new Shah of Persia.[12]

The majority of the Persian people, however, rejected the Afghan regime as usurpers from the start. For the next seven years until 1729, the Hotaks were the de facto rulers of most of Persia, and the southern and eastern areas of Afghanistan still remained under their control until 1738.

The Hotak dynasty was a troubled and violent one from the very start as internecine conflict made it difficult to establish permanent control. The dynasty lived under great turmoil due to bloody succession feuds that made their hold on power tenuous, and after the massacre of thousands of civilians in Isfahan – including more than three thousand religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family – the Hotak dynasty was eventually removed from power in Persia.[13]

On 8 March 1722, at the Battle of Gulnabad, Shah Mahmud defeated a much larger Persian army and laid siege to Isfahan itself. After six months the people of Isfahan were reduced to eating rats and dogs.[14]

— Jonathan L Lee, Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present (2018)

On the other hand, the Afghans had also been suppressed by the Iranian Safavid government represented by its governor Gurgin Khan before their uprising in 1709.[7]

Decline

Ashraf Hotak, who took over the monarchy following Shah Mahmud's death in 1725, and his soldiers were crushingly defeated in the October 1729 Battle of Damghan by Nader Shah Afshar, an Iranian soldier of fortune from the Sunni Afshar tribe, and the founder of the Afsharid dynasty that replaced the Safavids in Persia. Nader Shah had driven out and banished the remaining Ghilji forces from Persia and began enlisting some the Abdali Afghans of Farah and Kandahar in his military. Nader Shah's forces (among them were Ahmad Shah Abdali and his 4,000 Abdali troops) conquered Kandahar in 1738. They besieged and destroyed the last Hotak seat of power, which was held by Hussain Hotak (or Shah Hussain).[10][15] Nader Shah then built a new town nearby, named after himself, "Naderabad". The Abdalis were also restored to the general area of Kandahar, with the Ghilji's being pushed back to their former stronghold of Kalat-i Ghilji—an arrangement that lasts to the present day.

List of rulers

| Part of a series on |

| Pashtuns |

|---|

| Kingdoms |

| Name | Picture | Reign started | Reign ended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mirwais Hotak |

1709 | 1715 | |

| Abdul Aziz Hotak |

|

1715 | 1717 |

| Mahmud Hotak |

|

1717 | 1725 |

| Ashraf Hotak |

|

1725 | 1729 |

| Hussain Hotak |

|

1729 | 1738 |

Notes

- Shah Hussain Hotak wrote poetry in Pashto and Persian.[1]

References

- Bausani 1971, p. 63.

- Malleson, George Bruce (1878). History of Afghanistan, from the Earliest Period to the Outbreak of the War of 1878. London: Elibron.com. p. 227. ISBN 1402172788. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Ewans, Martin; Sir Martin Ewans (2002). Afghanistan: a short history of its people and politics. New York: Perennial. p. 30. ISBN 0060505087. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 9780823938636. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- Nadir Shah and the Afsharid Legacy, The Cambridge history of Iran: From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic, Ed. Peter Avery, William Bayne Fisher, Gavin Hambly and Charles Melville, (Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 11.

- Otfinoski, Steven Bruce (2004). Afghanistan. Infobase Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780816050567. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Runion, Meredith L. The History of Afghanistan. p. 63.

- "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 29. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- "Last Afghan empire". Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree and others. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- "Account of British Trade across the Caspian Sea". Jonas Hanway. Centre for Military and Strategic Studies. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Axworthy pp.39-55

- "AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF PERSIA DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward Granville Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 31. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present, page 78

- "AFGHANISTAN x. Political History". D. Balland. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

Sources

- Bausani, Alessandro (1971). "Pashto Language and Literature". Mahfil. Asian Studies Center. Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (Spring - Summer): 55–69.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hotak dynasty. |