Archibald Forbes

Archibald Forbes (17 April 1838 – 30 March 1900) was a Scottish war correspondent.[1][2][3]

Archibald Forbes | |

|---|---|

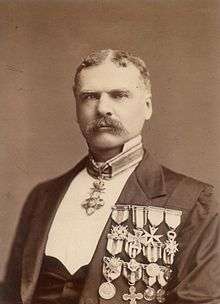

Archibald Forbes, by Elliott & Fry, c. 1880s. | |

| Born | 17 April 1838 Morayshire, Scotland |

| Died | 17 April 1900 (aged 62) Clarence Terrace, London |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | War correspondent |

Early life and family

He was the son of Very Rev Lewis William Forbes DD (1794–1854), minister of Boharm, Banffshire, and Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1852, and his second wife, Elizabeth Leslie, daughter of Archibald Young Leslie of Kininvie. He was born in Morayshire in 1838.[4]

After studying at the University of Aberdeen from 1854 to 1857, he went to Edinburgh, and after hearing a course of lectures by (Sir) William Howard Russell, the famous correspondent, he enlisted in the Royal Dragoons. While still a trooper he began writing for the Morning Star, and succeeded in getting several papers on military subjects accepted by the Cornhill Magazine.[4]

Early career

On being invalided from the army in 1867,[5] he started and ran with very little external aid a weekly journal called the London Scotsman (1867–71). His chance as a journalist came when in September 1870 he was despatched to the siege of Metz by the Morning Advertiser (from which paper, however, his services were transferred after a short period to the Daily News). In all the previous reports from battlefields comparatively sparing use had been made of the telegraph.[4]

Forbes laments his own supineness in the matter of wiring full details from the scene of operations. But the intensity of competition rapidly developed the long war telegram during the autumn of 1870, and no one contributed more effectively to this result than Forbes. He witnessed many of the events of the autumn campaign and entered Paris with the Prussians (with whom he established excellent relations) on 1 March 1871. On this occasion he was nearly drowned in a Parisian fountain as a German spy by an enthusiastic French mob. He managed to arrive first in England with his account of the Prussian entry. Two months later he returned to Paris and witnessed the horrors of the commune with the sang froid for which he became celebrated.[4]

Later work

In 1873, he represented the Daily News at the Vienna exhibition; subsequently he saw fighting in Spain, both with the Carlists and their opponents ; and in 1875 he accompanied the Prince of Wales on his visit to India. In 1876, he was with Michael Gregorovitch Tchernaieff and the Russian volunteers in the Serbian campaign of 1876. In 1877, he witnessed the Russian invasion of Turkey, and on 23 August was presented to Alexander II at Gornic Studen as the bearer of important news from the Schipka Pass. On this occasion, the emperor conferred upon him the order of St. Stanislaus for his services to the Russian soldiers before Plevna. During 1878, after a brief visit to Cyprus to witness the British occupation,[5] he lectured in England upon the Russo-Turkish war. In 1878-9 he went out to Afghanistan, and accompanied the Khyber Pass force to Jellalabad. He was present at the capture of Ali Musjid, and marched with several expeditions against the hill tribes.[5]

From Afghanistan, he went to Mandalay and had interviews with Thibaw Min. In 1880, he was with Lord Chelmsford as a British force was preparing for the Zulu war. On 5 July, after the victory of Ulundi, he rode 110 miles to Landman's Drift in twenty hours. Two days after his arrival there he appeared in a state of utter exhaustion before Pietermaritzburg, having ridden by way of Ladysmith and Estcourt, an additional 170 miles, in thirty-five hours.

The news of Ulundi first reached England through his agency, he having completely outpaced the official despatch rider. He put in a claim for the Avar medal on the strength of this piece of service, but the request was refused with scant courtesy by the war office.

Some of his criticisms of Lord Chelmsford were held in certain quarters to have been unnecessarily offensive. Forbes had seen war practically illustrated in all quarters of the globe, and he had outgrown any semblance of diffidence in passing judgment upon difficult military operations.[4]

Forbes had already published several volumes of Daily News war correspondence. That relating to 1870–1 was widely circulated. During his later years he collected a quantity of his various material and published it in book form. In 1884, upon the occasion of Gordon's mission to the Sudan, he brought out a tolerable sketch of his career, Chinese Gordon (13th edit. 1886). This was followed by a volume of military sketches and tales, Barracks, Bivouacs, and Battles (1891), and a brief tableau of The Afghan Wars of 1839 and 1879 (1892, 8vo). Then came a version of Moltke's Franco-German War ('revised by A. Forbes,' 1893), and The Great War of 189-, a cleverly written forecast, in which Forbes collaborated with a number of other experts and special correspondents, such as Admiral Philip Howard Colomb, Colonel (Sir) Frederick Maurice, and others. In 1895, appeared the best volume of Forbes's autobiographical sketches, Memories and Studies of War and Peace.[6]

In this he claimed, among The Soldiers I have known, Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, Ulysses S. Grant, Sherman, Robert Napier, Mikhail Skobelev, Osman Pasha, Sir Redvers Buller, and Lords Wolseley and Roberts. His readiness to prophesy no less than to judge suggests a rashness in forming opinions, inseparable perhaps from the profession that he followed; but he has some good stories, such as the one of General Skobeleff arresting his father (a miserly parent) for reporting himself in undress uniform.[7] In 1896, Forbes collaborated in two handsome but ill-arranged quarto volumes of Battles of the Nineteenth Century, and in the same year published his historical record of The Black Watch. In 1898, he committed to the press a superficial Life of Napoleon III (with portraits), based to a large extent upon the Life by Blanchard Jerrold. Previous biographies by Forbes of similar calibre were those of the Emperor William II (1889), Havelock (1890), and Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde (1895, Men of Action series).[4]

After a life of perilous adventure, Forbes died peacefully at Clarence Terrace, Regent's Park, on 30 March 1900, and he was buried in the Allenvale cemetery, near Aberdeen.[8]

He left a widow, Louisa, daughter of Montgomery C. Meigs.

A portrait of Forbes is prefixed to his Memories and Studies (1895). A tablet with a medallion portrait was unveiled in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in May 1902 by Field Marshal Viscount Wolseley.[9]

References

- Roth, Mitchel P. (1997). "Forbes, Archibald". Historical Dictionary of War Journalism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-313-29171-3.

- "FORBES, ARCHIBALD". The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. X (EVANGELICAL CHURCH to FRANCIS JOSEPH) (11th ed.). Cambridge, England and New York: At the University Press. 1910. pp. 636–637. Retrieved 23 July 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Bullard, F. Lauriston (1914). "ARCHIBALD FORBES". Famous War Correspondents. Boston: Little, Brown & Company. pp. 69–114. Retrieved 29 July 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Seccombe 1901.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 636–637.

- Forbes, Archibald (1895). Memories and Studies of War and Peace (2nd ed.). London, Paris & Melbourne: Cassell and Company Limited. Retrieved 23 July 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Forbes, Archibald (1895). Memories and Studies of War and Peace (2nd ed.). London, Paris & Melbourne: Cassell and Company Limited. pp. 365–366. Retrieved 26 July 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- "Archibald Forbes Dead. War Correspondent Expires in London After a Long Illness". The New York Times. 30 March 1900. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "Archibald Forbes Memorial". The Times (36783). London. 2 June 1902. p. 4.

- Attribution

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archibald Forbes. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Archibald Forbes |

- Works by Archibald Forbes at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Archibald Forbes at Internet Archive

- Works by Archibald Forbes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Archibald Forbes at Unz.org

- Portraits of Archibald Forbes at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Archibald Forbes at Find a Grave