Kabul Expedition (1842)

The Battle of Kabul was part of a punitive campaign undertaken by the British against the Afghans following the disastrous retreat from Kabul. Two British and East India Company armies advanced on the Afghan capital from Kandahar and Jalalabad to avenge the complete annihilation of a small military column in January 1842. Having recovered prisoners captured during the retreat, the British demolished parts of Kabul before withdrawing to India. The action was the concluding engagement to the First Anglo-Afghan War.

Background

In the late 1830s, the British government and the British East India Company became convinced that Emir Dost Mohammed of Afghanistan was courting Imperial Russia. They arranged passage through Sindh for an army which invaded Afghanistan and restored the former ruler Shuja Shah Durrani, who had been deposed by Dost Mohammed thirty years earlier and who had been living as a pensioner in India. They also agreed safe passage for supplies and reinforcements with Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire, in return for inducing Shah Shuja to formally cede the disputed region of Peshawar to him.[1]

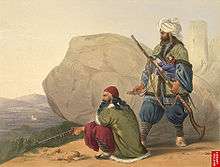

The British captured Kabul, and Dost Mohammed surrendered himself into British custody in November 1840. Over the next year, complacent British commanders withdrew some of their forces even as popular resistance grew. They also ceased paying subsidies to the Ghilzais, who controlled the routes between Kabul and Peshawar. A brigade commanded by Brigadier Robert Sale was sent in October 1841 from Kabul to clear the route to India via the Khyber Pass, but faced opposition from Ghilzai tribesmen all the way, and was blockaded in Jalalabad, halfway to the Khyber Pass.

In November 1841, there was a popular uprising in Kabul, in which the Resident Political Agent Alexander Burnes was murdered. The ineffectual commander of the Kabul garrison, General William George Keith Elphinstone, failed to react to the uprising. Dost Mohammed's son Akbar Khan, arrived to lead the insurrection. Elphinstone asked for reinforcements from Major General William Nott, commanding at Kandahar. Nott unwillingly dispatched a brigade under Brigadier MacLaren but it was turned back by heavy snowfalls.

William Hay Macnaghten, the Minister to Shah Shujah's court, attempted to sow dissension within the insurgent ranks and even arrange for Akbar Khan to be assassinated, but Akbar Khan was informed of his planned treachery and murdered Macnaghten at a meeting on 23 December.[2] Finally, with his troops blockaded in an indefensible encampment outside Kabul, Elphinstone signed a convention with Akbar Khan by which his army was to evacuate Kabul, and was guaranteed safe passage to Jalalabad. The result was the slaughter of Elphinstone's army of 4,500 British and Indian soldiers and 12,000 camp followers by tribesmen in January 1842. Only one British surgeon and a handful of Indian sepoys reached Jalalabad. Elphinstone and several officers and their families surrendered themselves as hostages and were taken prisoner.

British situation

Lord Auckland, the Governor General of India, was said to have aged ten years overnight on hearing of the disaster.[3] He nevertheless dispatched Major General George Pollock with reinforcements to Peshawar. Here, a brigade of Bengal units commanded by Brigadier Wild, with a Sikh contingent, had made an ineffectual attempt to break through the Khyber Pass in late December 1841. The Sikhs had deserted and the Bengal units were demoralised by cold, lack of clothing and rumours of the disaster to Elphinstone's army. Pollock's orders were to restore the efficiency of the troops at Peshawar and relieve the besieged garrison of Jalalabad. Auckland was already due to be replaced as Governor General by Lord Ellenborough, whose ship arrived off Madras on 21 February. Before officially taking up his appointment, Ellenborough wrote that he intended to restore British prestige and honour.

The British still held several garrisons in Afghanistan: at Kandahar under Nott, at Ghazni on the route between Kandahar and Kabul, and at Jalalabad under Sale. The captive General Elphinstone had sent orders to the other garrison commanders that they were to evacuate their positions under the terms of the capitulation he had agreed with Akbar Khan. (Elphinstone died in April, still a captive.) Nott and Sale ignored Elphinstone's order, but Colonel Thomas Palmer at Ghazni obeyed it, withdrawing from the easily defended citadel into vulnerable buildings in the city.[4] Shah Shuja still held the fortress of Bala Hissar in Kabul and was attempting to bribe chiefs and tribes to his cause, although he was no longer supported by the British. He even attempted to improve his standing within Afghanistan by demanding that the British comply with the terms Elphinstone had agreed with Akbar Khan.[5]

Developments in March and April

During the late winter and spring, there was fighting around all the British-held enclaves.

On 10 February, Nott led a force from Kandahar against the tribes blockading him. The Afghans, under a wily chief named Mirza Ahmed, bypassed him and attacked the city, setting fire to a gate to gain entry. They were driven off by the small garrison left by Nott, suffering heavy casualties.[6] Nott's supplies were running short, and a brigade under Brigadier England which tried to reach him from Quetta with supplies was repulsed. With Kandahar no longer directly threatened, Nott sent a substantial detachment to rendezvous with England and escort him to Kandahar.

On 6 March, the troops at Ghazni (the 27th Bengal Native Infantry) came under attack in their temporary quarters. After resisting for two and a half weeks, they were forced to surrender. The sepoys who refused to convert to Islam were murdered, and the British officers and their families became prisoners of Akbar Khan.[7]

On 31 March, Pollock completed restoring the morale of the sepoys at Peshawar and forced his way through the Khyber Pass. He sent his troops up the heights on either side of the pass to outflank the defenders, and succeeded with very few casualties. He reached Jalalabad on 14 April, to find the siege already lifted. After wavering for some weeks, Sale had led a sortie by the garrison of Jalalabad on 19 February, to capture grazing sheep to replenish his supplies of food. He repeated the sortie on 7 April, defeating the besiegers and forcing them to raise the siege.

While Akbar Khan had been absent conducting the siege of Jalalabad, Shah Shuja had restored his authority around Kabul. After temporising for several weeks and secretly asking for British help from India, he reluctantly emerged from the Bala Hissar at the end of March to join the jihad proclaimed by Akbar Khan. He was assassinated by adherents of Nawab Zaman Khan, an influential chieftain who resented the favour shown by Shah Shuja to his rival Naib Aminullah Khan. One of the assassins was Shah Shuja's godson, Shuja' al-Daula.[8] Shah Shuja's son Futteh Jung proclaimed himself his father's successor, but had even less support than his father.

Battle

In India, Lord Ellenborough had softened his earlier attitude. His primary objective was to avoid the expense of a long war. He ordered Nott and Pollock to retreat, arguing that once the British had evacuated Afghanistan, negotiations with Akbar Khan for the release of the hostages could proceed calmly.[9] Ellenborough was opposed by his generals and by the government in Britain, all of whom insisted that stern retribution was required. He accordingly modified his orders. Pollock and Nott were again ordered to retreat, but Nott was allowed to retreat by way of Kabul if he chose, making a detour of over 300 miles (480 km), and Pollock was also permitted to move to Kabul to cover Nott's retreat. The late nineteenth-century historian John William Kaye wrote that, "No change had come over the views of Lord Ellenborough, but a change had come over the meaning of certain words in the English language."[10]

Nott began his "retreat" on 9 August. He sent the bulk of his troops and camp-followers back to Quetta but began advancing north to Kabul with two British regiments (the 40th Foot and the 41st Foot), some sepoy regiments which had earlier distinguished themselves and four batteries of artillery, 6,000 men in total. On 30 August, he defeated a force of 10,000 Afghans at Khelat-i-Ghilzai near Ghazni. He captured Ghazni itself without opposition, and looted the city in retaliation for the attack on Palmer. Lord Ellenborough had specifically ordered him to recover a set of ornate sandalwood gates, known as the Somnath Gates, which had been looted from India by the Afghan rulers and hung at the tomb of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.[11] A whole sepoy regiment, the 43rd Bengal Native Infantry (which later became the 6th Jat Light Infantry after the Indian Rebellion of 1857), was detailed to carry the gates back to India.[12] Nott's force arrived at Kabul on 17 September.

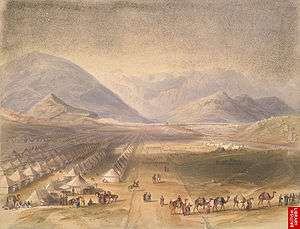

Pollock's army, which was widely termed the "Army of Retribution", meanwhile advanced from Jalalabad. The army consisted of four brigades, one of which was made wholly of British troops. It numbered about 8,000 men in total. After a sharp engagement on 13 September, they defeated some 15,000 tribesmen deployed by Akbar Khan at the Tezin Pass, and the way to Kabul was clear. Pollock's troops came across many skeletons and unburied bodies from Elphinstone's army and, in spite of orders from Ellenborough and Pollock to show restraint, they committed many brutal reprisals against villages and their inhabitants.[13] Pollock reached Kabul on 15 September, two days before Nott.

As the British advanced, the hostages in Akbar Khan's hands were treated less severely than previously, although they were moved to Bamian to keep them out of reach of the British armies. Nott was urged to send cavalry to rescue the hostages, but he declined to do so (possibly as a result of a minor disaster on 29 August, when his cavalry had suffered heavy losses in a mishandled attack). Instead, Pollock sent Qizilbashi irregular cavalry under Richmond Shakespeare (his Military Secretary) and infantry under Brigadier Sale to rescue them. They found that when news of the Afghan defeats reached their guards, the hostages, including Sale's own wife, had negotiated their own release in return for payments. In all, thirty-five British officers, fifty-one private soldiers, twelve officers' wives and twenty-two children who had been taken hostage by Akbar Khan were released.[14]

A detachment from Pollock's army laid waste to Charikar, in revenge for the destruction and massacre of an small irregular Gurkha detachment there the previous November. Finally, Pollock ordered the historic covered bazaar of Kabul to be destroyed. Although he issued orders that the rest of the city was to be spared, discipline in the army broke down and there was widespread looting and destruction. Even the Persian-speaking Shia Qizilbashis, who were opposed to Akbar Khan, and many Indian merchants were ruined.[15]

Not all of the Indian sepoys of Elphinstone's army had died in the retreat. Perhaps 2000, many of whom had lost limbs to frostbite, had returned to Kabul to be sold into slavery or to exist by begging.[16] Pollock was able to release many of them, but many others were left behind in the surrounding hills when his forces precipitately retreated in November 1842.[17]

Final evacuation

Pollock's army then retired through Jalalabad to Peshawar. Futteh Jung handed over power to another nominee and accompanied the retreating army.[18]

The withdrawal from Kabul was an arduous march, harassed from Gandamak onwards by Afghan tribesmen. Although the march was far better organised than Elphinstone's retreat, large numbers of stragglers were left behind to be rescued by the rearguard or abandoned to die. Part of one division commanded by General McGaskill was ambushed near Ali Masjid at the narrowest point of the Khyber Pass on 3 November and destroyed. Casualties mounted due to snipers and ambushes until the troops were within sight of Jamrud Fort and safety.[19]

Aftermath

Within three months of the final British withdrawal, the British allowed Dost Mohamed to return from India to resume his rule. Akbar Khan died in 1845. (It was sometimes supposed that he had been poisoned by his father, who feared his ambition.) Dost Mohamed's subsequent relations with the British were equivocal until his death. He half-heartedly supported the Sikhs during the Second Anglo-Sikh War in return for a promise that Peshawar would be restored to Afghan rule, but the British never abandoned the city. He remained neutral when the Indian Rebellion of 1857 broke out. British policy was to avoid expeditions into Afghanistan for nearly forty years.

The supposed Somnath Gates which had been laboriously carried back to India were paraded through the country, but were declared to be fakes by Hindu scholars. (Henry Rawlinson, a political agent attached to Nott's force, had already warned Ellenborough that this was the case.) They were eventually installed at Agra.[12]

An infantry battalion (the Khelat-i-Ghelzai regiment} and an artillery battery from Shah Shuja's army retreated to India with the British armies. They were taken into the East India Company's army and the artillery unit eventually became part of the British army. (It survives to this day as T (Headquarters) Battery, 12th Regiment Royal Artillery.)

Order of Battle

The British order of battle was;[20]

General Pollock's Army

British Army

- 3rd Light Dragoons (Hussars)

- 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot

- 13th (1st Somersetshire, Prince Albert's Light Infantry) Regiment of Foot

- 31st (Huntingdonshire) Regiment of Foot

Bengal Presidency Army

- 1st Bengal Light Cavalry

- 10th Bengal Light Cavalry

- Two regiments of the Bengal Irregular Cavalry

- 6th Bengal Native Infantry

- 26th Bengal Native Infantry

- 30th Bengal Native Infantry

- 33rd Bengal Native Infantry

- 35th Bengal Native Infantry

- 53rd Bengal Native Infantry

- 60th Bengal Native Infantry

- 64th Bengal Native Infantry

- Two batteries of the Bengal Horse Artillery

- Three batteries of the Bengal Field Artillery

- Battery of the Bengal Mountain Artillery

Brigadier Nott's Army

British Army

Bengal Presidency Army

- 3rd Bombay Light Cavalry

- Skinner's Horse

- Regiment of Irregular Horse

- 16th Bengal Native Infantry

- 38th Bengal Native Infantry

- 42nd Bengal Native Infantry

- 43rd Bengal Native Infantry

- 12th Khelat-i-Ghilzai Regiment (Mughal, not Bengal)

- Two batteries of the Bengal Horse Artillery

- Two batteries of the Bengal Field Artillery

Notes

Citations

- Hopkirk (1990), p.189

- Dalrymple (2013), pp. 348–353

- Hopkirk (1990), p.270

- Allen (2000), p.44

- Forbes (1892), Chapter VIII

- Forbes (1892), p.107

- Allen (2000), pp.44–45

- Dalrymple (2013), pp.417–421

- Hopkirk (1990), p.272

- Hopkirk (1990), p.273

- Dalrymple (2013), pp.444–445

- "britishbattles.com". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- Allen (2000), pp.50–52

- Dalrymple (2013), p.387

- Hopkirk (1990), pp.276–277

- Dalrymple (2013), pp.387–388

- Dalrymple (2013), pp.462–463

- Forbes (1892), p.69

- Allen (2000), p.52-56

- "Battle of Kabul 1842". www.britishbattles.com. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

References

- Allen, Charles (2000). Soldier Sahibs. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11456-0.

- Dalrymple, William (2013). Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978 1 4088 1830 5.

- Forbes, Archibald (1892). The Afghan Wars 1839–42 and 1878–80. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-4264-2938-5.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1990). The Great Game: on Secret Service in High Asia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282799-5.

External links

- "britishbattles.com". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.