Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo–Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the "war with those in the red coats" or "War with the English"), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherokee Rebellion. The war was a conflict between British forces in North America and Cherokee Indian tribes during the French and Indian War. The British and the Cherokee had been allies at the start of the war, but each party had suspected the other of betrayals. Tensions between British-American settlers and the Cherokee increased during the 1750s, culminating in open hostilities in 1758.

Prelude

After siding with the Province of Carolina in the Tuscarora War of 1711–1715, the Cherokee had turned on their British allies at the outbreak of the Yamasee War of 1715–1717, until switching sides, once again, midway through the war. This action ensured the defeat of the Yamasee. The Cherokee then remained allies of the British until the French and Indian War.

At the 1754 outbreak of the war, the Cherokee were allies of the British, taking part in campaigns against Fort Duquesne (at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and the Shawnee of the Ohio Country. In 1755, a band of Cherokee 130-strong under Ostenaco (or Ustanakwa) of Tamali (Tomotley) took up residence in a fortified town at the mouth of the Ohio River at the behest of the Iroquois (who were also British allies).[1]

For several years, French agents from Fort Toulouse had been visiting the Overhill Cherokee on the Hiwassee and Tellico Rivers, and had made inroads into those places. The strongest pro-French Cherokee leaders were Mankiller (Utsidihi) of Talikwa(Tellico Plains), Old Caesar of Chatuga (or Tsatugi, Chatooga), and Raven (Kalanu) of Ayuhwasi (Hiwassee) . The "First Beloved Man" (or Uku) of the nation, Conocotocko (called "Old Hop"), was very pro-French, as was his nephew, Conockotocko ("Standing Turkey"), who succeeded him at his death in 1760.[2]

The former site of the Coosa Chiefdom was reoccupied in 1759 by a Muscogee contingent under Big Mortar (Yayatustanage) in support of the pro-French Cherokee then residing in Great Tellico and Chatuga. This was a step toward his planned alliance of Muscogee, Cherokee, Shawnee, Chickasaw, and Catawba (which would have been the first of its kind in the South). Although such an alliance did not come into being until the days of Dragging Canoe, Big Mortar still rose to leading chief of the Muscogee after the French and Indian War.[3][4]

Early stages

The Anglo–Cherokee War broke out in 1758 when Virginia militia attacked Moytoy (Amo-adawehi) of Citico in retaliation for the alleged theft of some horses by the Cherokee. Moytoy's reaction was to lead retaliatory raids on the Yadkin and Catawba Rivers in North Carolina[5] which began a domino effect that ended with the murders of 23 Cherokee hostages at Fort Prince George near Keowee and the massacre of the garrison of Fort Loudoun near Chota (Itsati).

These events ushered in a war which didn't end until 1761. The Cherokee were led by Aganstata of Chota, Attakullakulla (Atagulgalu) of Tanasi, Ostenaco of Tomotley, Wauhatchie (Wayatsi) of the Lower Towns, and Round O of the Middle Towns.

During the second year of the French and Indian War, the British had sought Cherokee assistance against the French and their Indian allies.

The English had reports, which proved accurate, that indicated the French were planning to build forts in Cherokee territory (as they had already done with Ft. Charleville at Great Salt Lick on the Cumberland River); Ft. Toulouse, near present-day Montgomery, Alabama; Ft. Rosalie at Natchez, Mississippi; Ft. St. Pierre at modern day Yazoo, Mississippi; and Ft. Tombeckbe on the Tombigbee River). Once the Cherokee agreed to be their allies, the British hastened to build forts of their own in the Cherokee lands, completing Fort Prince George near Keowee in South Carolina (among the Lower Towns); and Fort Loudoun (near Chota at the mouth of the Tellico River) in 1756. Once the forts were built, the Cherokee raised close to 700 warriors to fight in western Virginia Colony under Ostenaco. Oconostota and Attakullakulla led another large group to attack Fort Toulouse.

In 1758, the Cherokee participated in the taking of Fort Duquesne (present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.) However, they felt their efforts were unappreciated. While traveling through Virginia, on their way home, several Cherokee were murdered by Virginians. The Cherokee had been promised supplies, but misunderstood where they were to get them from. After taking some horses they believed were rightly theirs, several Virginians killed and scalped between 30 and 40 of them. Later, the Virginians claimed the scalps as those of Shawnees and collected bounties for them.[6]

War

While some Cherokee leaders still called for peace, others led retaliatory raids on outlying pioneer settlements. The Cherokee finally declared open war against the British in 1759. A number of Muskogee under Big Mortar moved up to Coosawatie. These people had long been French allies in support of the Cherokee pro-French faction centered in Great Tellico.

The governor of South Carolina, William Henry Lyttelton, embargoed all gunpowder shipments to the Cherokee and raised an army of 1,100 men which marched to confront the Lower Towns of the Cherokee. Desperate for ammunition for their fall and winter hunts, the nation sent a delegation of moderate chiefs to negotiate. The twenty-nine chiefs were taken prisoner[7] as hostages and sent to Fort Prince George, escorted by the provincial army,.[7] Lyttleton thought this would ensure peace.

Governor Lyttleton returned to Charleston, but the Cherokee were still angry, and continued to attack frontier settlements into 1760. In February 1760, they attacked Fort Prince George in an attempt to rescue their hostages. The fort's commander was killed. His replacement massacred[8] all of the hostages and fended off the attack. The Cherokee also attacked Fort Ninety Six, but it withstood the siege.

The Cherokee expanded their retaliatory campaign into North Carolina, as far east as modern day Winston-Salem. An attack on Fort Dobbs in North Carolina was repulsed by General Hugh Waddell. However, lesser settlements in the North and South Carolina back-country quickly fell to Cherokee raids.

Governor Lyttleton appealed for help to Jeffrey Amherst, the British commander in North America. Amherst sent Archibald Montgomerie with an army of 1,200 troops (the Royal Scots and Montgomerie's Highlanders) to South Carolina. Montgomerie's campaign razed some of the Cherokee Lower Towns, including Keowee. It ended with a defeat at Echoee (Itseyi) Pass when Montgomerie tried to enter the Middle Towns territory. Later in 1760, the Overhill Cherokee defeated the British colonists at Fort Loudoun and took it over.

In 1761, Montgomerie was replaced by British army officer James Grant. He led an army of 2,600 men (the largest force to enter the southern Appalachians to date) against the Cherokee. His army moved through the Lower Towns, defeated the Cherokee at Echoee Pass, and proceeded to raze about 15 Middle Towns while burning fields of crops along the way.

Treaties

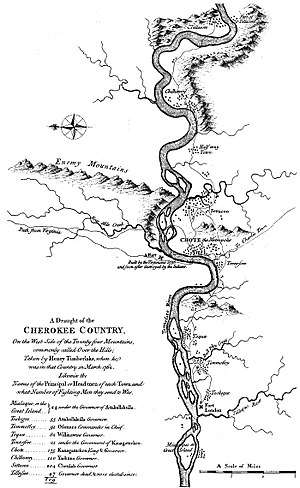

In November 1761, the Cherokee signed the Treaty of Long-Island-on-the-Holston with the Colony of Virginia. They made peace with South Carolina the following year in the Treaty of Charlestown. During the Timberlake Expedition, Lt. Henry Timberlake, Sgt. Thomas Sumter, John McCormack (who served as their interpreter), and an unknown servant traveled into the Overhill settlements area to deliver a copy of the treaty with Virginia to the Cherokee. Timberlake's diary and map of his journey (see above), were published in 1765. His diary contained what historians assessed was an accurate description of Cherokee culture.

Pro-French leader, Standing Turkey, was deposed and replaced as "First Beloved Man" with the pro-British Attakullakulla. John Stuart became British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern District, based out of Charlestown, South Carolina, and was the main liaison between the Cherokee and the British government. His first deputy, Alexander Cameron, lived among the Cherokee, first at Keowee, then at Toqua on the Little Tennessee River, while his second deputy, John McDonald, resided a hundred miles to the southwest on the west side of Chickamauga Creek where it was crossed by the Great Indian Warpath.

During the war, a number of Cherokee towns had been destroyed under General Grant and were never reoccupied. The most notable of these was Kituwa, the inhabitants of which migrated west, taking up residence at Great Island Town (on the Little Tennessee), living among the Overhill Cherokee.[9] As a result of the war, Cherokee warrior strength estimated at 2,590 before the war in 1755[10] was now reduced by battle, smallpox and starvation to 2,300.[11]

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the war, French Louisiana east of the Mississippi went to the British, along with Canada, while Louisiana west of the Mississippi went to Spain; in return, Spanish Florida went to Britain, which divided it into East Florida and West Florida.

After the signing of the treaties and the conclusion of the Timberlake Expedition, Henry Timberlake visited London with three Cherokee leaders: Ostenaco, Standing Turkey, and Wood Pigeon (Ata-wayi).[12] The Cherokee guests visited the Tower of London, met the playwright Oliver Goldsmith, drew massive crowds, and had an audience with King George III. On the voyage to England, their interpreter, William Shorey, died. This made communication nearly impossible.

Hearing of the Cherokees' warm welcome in London, South Carolinians viewed their reception as a sign of imperial favoritism at the colonists' expense, especially in view of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (which prohibited settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains), and was a foundation of one of the major irritants for the colonials leading up to the American Revolution.

See also

References

- Tanner, p. 95

- Brown, Eastern Cherokee Chiefs

- Heard, p. 255

- Adair, pp. 254-256, 268-272

- Oliphant, pp. 72-78, 110-111

- Mooney, p. 41. Anderson, p. 458.

- Anderson, p. 460.

- Anderson, p. 461.

- Klink and Talman, p. 62

- Mooney, p. 39, 2,590 in 1755; 5,000 in 1739 before the great smallpox epidemic.

- Mooney, p. 45.

- Evans, Ostenaco

Sources

| Library resources about Anglo-Cherokee War |

- "Cherokee War (1760–1762), Rice Hope Plantation Inn

- Adair, James. History of the American Indian. Nashville: Blue and Gray Press, 1971.

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0-375-40642-5. See ch. 47, "The Cherokee War and Amherst's Reforms in Indian Policy", pp. 457–71.

- Brown, John P. Old Frontiers: The Story of the Cherokee Indians from Earliest Times to the Date of Their Removal to the West, 1838. Kingsport: Southern Publishers, 1938.

- Evans, E. Raymond. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Ostenaco". Journal of Cherokee Studies, 1:1 (Summer 1976), pp. 41–54.

- French, Captain Christopher. "Journal of an Expedition to South Carolina", Journal of Cherokee Studies 3:2 (Summer 1977), pp. 275–302.

- Hatley, Thomas. The Dividing Paths: Cherokees and South Carolinians through the Era of Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Heard, J. Norman. Handbook of the American Frontier, The Southeastern Woodlands: Four Centuries of Indian-White Relationships. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1993.

- Kelly, James C. "Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Attakullakulla." Journal of Cherokee Studies 3:1 (Winter 1978), pp. 2–34.

- Kelly, James C. "Oconostota", Journal of Cherokee Studies 3:4 (Fall 1978), pp. 221–238.

- King, Duane H. The Cherokee Indian Nation: A Troubled History. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979.

- Maass, John R. The French and Indian War in North Carolina: The Spreading Flames of War. Charleston: The History Press, 2013. ISBN 1-609-49887-9

- Mooney, James. Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee. Nashville: Charles and Randy Elder-Booksellers, 1982. Also Dover, 1995.

- Oliphant, John. Peace and War on the Anglo-Cherokee Frontier, 1756–63. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Timberlake, Henry. The Memoirs of Lt. Henry Timberlake: The Story of a Soldier, Adventurer, and Emissary to the Cherokees, 1756-1765. Edited by Duane H. King. Cherokee, N.C.: Museum of the Cherokee Indian Press, 2007.

- Tortora, Daniel J. Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. ISBN 1-469-62122-3.

- Williams, Samuel Cole. Early Travels in the Tennessee Country, 1540–1800. Johnson City: Watauga Press, 1928.