Tahirid dynasty

The Tahirid dynasty (Persian: طاهریان, romanized: Tâheriyân, pronounced [t̪ʰɒːheɾiˈjɒːn]) was a dynasty, of Persian[5] dehqan[6] origin, that effectively ruled the Khorasan from 821 to 873 while other members of the dynasty served as military and security commanders for the city of Baghdad from 820 until 891.[lower-alpha 1][7] The dynasty was founded by Tahir ibn Husayn, a leading general in the service of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun. Their capital in Khorasan was initially located at Merv but was later moved to Nishapur. The Tahirids have been described as the first independent Iranian dynasty after the fall of the Sassanian Empire.[8] However, according Hugh Kennedy: "The Tahirids are sometimes considered as the first independent Iranian dynasty, but such a view is misleading. The arrangement was effectively a partnership between the Abbasids and the Tahirids." Instead, the Tahirids were loyal to the Abbasid caliphs and enjoyed considerable autonomy rather than being independent from the central authority.[9][10] The tax revenue from Khorasan that was sent to the caliphal treasury was perhaps larger than those collected previously.[9]

Tahirid Dynasty Tâheriyân | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 821–873 | |||||||||

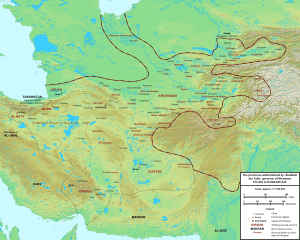

.png) Provinces governed by the Tahirids | |||||||||

| Status | Nominally part of the Abbasid Caliphate[1] | ||||||||

| Capital | Merv, later Nishapur | ||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (informal)[2] Arabic (literature/poetry/science)[3] | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Emirate | ||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||

• 821 | Tahir ibn Husayn | ||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||

• Established | 821 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 873 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 800 est.[4] | 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Related articles |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Turkmenistan |

|

| Periods |

|

Antiquity

|

|

Early modern history |

| Related historical names of the region |

|

|

Faravahar background | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Greater Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-Islamic BCE / BC

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rulers of Khurasan

Rise

The founder of the Tahirid dynasty was Tahir ibn Husayn, a general who had played a major role in the civil war between the rival caliphs al-Amin and al-Ma'mun. He and his ancestors had previously been awarded minor governorships in eastern Khorasan for their service to the Abbasids.[5] In 821, Tahir was made governor of Khorasan, but he died soon afterwards. The caliph then appointed Tahir's son, Talha, whose governorship lasted from 822–828.[11] Tahir's other son, Abdullah, was instated as the wali of Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula, and when Talha died in 828 he was given the governorship of Khorasan. Abdullah is considered one of the greatest of the Tahirid rulers,[11] as his reign witnessed a flourishing of agriculture in his native land of Khorasan, popularity in the eastern lands of the Abbasid caliphate and expanding influence due to his experience with the western parts of the caliphate.

The replacement of the Pahlavi script with the Arabic script in order to write the Persian language was done by the Tahirids in 9th century Khurasan.[12]

Fall

Abdullah died in 845 and was succeeded by his son Tahir II. Not much is known of Tahir's rule, but the administrative dependency of Sistan was lost to rebels during his governorship. Tahirid rule began to seriously deteriorate after Tahir's son Muhammad ibn Tahir became governor, due to his carelessness with the affairs of the state and lack of experience with politics. Oppressive policies in Tabaristan, another dependency of Khorasan, resulted in the people of that province revolting and declaring their allegiance to the independent Zaydi ruler Hasan ibn Zayd in 864.[11] In Khorasan itself, Muhammad's rule continued to grow increasingly weak, and in 873 he was finally overthrown by the Saffarid dynasty, who annexed Khorasan to their own empire in eastern Persia.

Governors of Baghdad

Besides their hold over Khorasan, the Tahirids also served as the military governors (ashab al-shurta) of Baghdad, beginning with Tahir's appointment to that position in 820. After he left for Khorasan, the governorship of Baghdad was given to a member of a collateral branch of the family, Ishaq ibn Ibrahim, who controlled the city for over twenty-five years.[13] During Ishaq's term as governor, he was responsible for implementing the Mihna (inquisition) in Baghdad.[14] His administration also witnessed the departure of the caliphs from Baghdad, as they made the recently constructed city of Samarra their new capital.[15] When Ishaq died in 849 he was succeeded first by two of his sons, and then in 851 by Tahir's grandson Muhammad ibn Abdallah.[13]

Abdallah played a major role in the events of the "Anarchy at Samarra" in the 860s, giving refuge to the caliph al-Musta'in and commanding the defense of Baghdad when it was besieged by the forces of the rival caliph al-Mu'tazz in 865. The following year, he forced al-Musta'in to abdicate and recognized al-Mu'tazz as caliph, and in exchange was allowed to retain his control over Baghdad.[16] Violent riots plagued Baghdad during the last years of Abdallah's life, and conditions in the city remained tumultuous after he died and was succeeded by his brothers, first Ubaydallah and then Sulayman.[17] Eventually order was restored in Baghdad, and the Tahirids continued to serve as governors of the city for another two decades. In 891, however, Badr al-Mu'tadidi was put in charge of the security of Baghdad in place of the Tahirids,[13] and the family soon lost their prominence within the caliphate after that.[11]

Language and culture

The Tahirids were highly Arabized in culture and outlook, and eager to be accepted in the Caliphal world where cultivation of things Arabic gave social and cultural prestige.[18] Due to this, the Tahirids were not part of the renaissance of New Persian language and culture.[18] The Persian language was at least tolerated in the entourage of the Tahirids, whereas the Saffarids played a leading part in the renaissance of Persian literature.[18]

Members of the Tahirid dynasty

| Governor[13] | Term |

|---|---|

| Governors of Khurasan | |

| Tahir ibn Husayn | 821-822 |

| Talha ibn Tahir | 822-828 |

| Abdallah ibn Tahir al-Khurasani | 828-845 |

| Tahir (II) ibn Abdallah | 845-862 |

| Muhammad ibn Tahir (II) | 862-873 |

| Governors of Baghdad | |

| Tahir ibn Husayn | 820-822 |

| Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Mus'abi | 822-850 |

| Muhammad ibn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim | 850-851 |

| Abdallah ibn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim | 851 |

| Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Tahir | 851-867 |

| Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Tahir | 867-869 |

| Sulayman ibn Abdallah ibn Tahir | 869-879 |

| Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah (again) | 879-885 |

| Muhammad ibn Tahir (II) | 885-890 |

| Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah (again) | 890-891 |

Family tree

Bold denotes a Tahirid that served as governor of Khorasan; italics denotes an individual who served as governor of Baghdad.[19]

| Mos'eb | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Husayn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tahir I 821–822 | Ibrahim | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Talha 822–828 | Abdallah 828–845 | Ishaq | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tahir II 845–862 | Muhammad | Ubaydallah | Sulayman | Muhammad | Abdullah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad 862–872 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Iranian Intermezzo

- List of Muslims

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Notes

- "The Taherids of Iraq. As the events of the late Taherid period demonstrate, the Taherids in Iraq were just about as powerful and important, even if less well known, than their Khorasani relatives. They regularly held positions as military commanders, heads of the security forces (ṣāheb al-šorṭa) for eastern and western Baghdad, and chief tax collectors or administrators (e.g., ʿāmel and moʿāwen) for the Sawād of Kufa."[7]

References

- Hovannisian & Sabagh 1995, p. 96.

- Canfield 1991, p. 6.

- Blair 2003, p. 340.

- Taagepera 1997, p. 475-504.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 90-91.

- Daftary 2003, p. 57.

- Daniel 2015.

- Waterson 2008, p. 820.

- Kennedy 2015, p. 139.

- Esposito 2000, p. 38.

- Bosworth 2000, p. 104-105.

- Lapidus 2012, p. 256.

- Bosworth 1996, p. 168-169.

- Turner 2006, p. 402.

- Gordon 2001, p. 47.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 135-139.

- Yar-Shater 2007, p. 124.

- Bosworth 1969, p. 106.

- Kraemer 1989, p. xxviii.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (1969). "The Ṭāhirids and Persian Literature". Iran. 7: 103–106. doi:10.2307/4299615. JSTOR 4299615.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bosworth, C. E. (1996). The New Islamic Dynasties. Columbia University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bosworth, C.E. (1975). "The Tahirids and Saffarids". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Bosworth, C.E. (2000). "Tahirids". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11211-1.

- Blair, S. (2003). "Language situation and scripts: Arabic". In Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, M.S. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV. Motilal Banarsidass.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Canfield, Robert L. (1991). "Introduction: the Turko-Persian tradition". In Canfield, Robert L. (ed.). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daftary, F. (2003). "Sectarian and national movements in Iran, Khurasan and Transoxanial during Umayyad in early Abbasid times". History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV. Motilal Banarsidass.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daniel, Elton L. (2015). "Taherids". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Esposito, John L. (2000). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199880416.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Hovannisian, Richard G.; Sabagh, Georges, eds. (1998). The Persian Presence in the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Third ed.). Oxford and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-78761-2.

- Kraemer, Joel L., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIV: Incipient Decline: The Caliphates of al-Wāthiq, al-Mutawakkil and al-Muntaṣir, A.D. 841–863/A.H. 227–248. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-874-4.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2012). Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521514415.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taagepera, Rein (1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 475–504. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- Turner, John P. (2006). "Ishaq ibn Ibrahim". In Meri, Josef W. (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization. 1. Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waterson, James (2008). The Ismaili Assassins: A History of Medieval Murder. Frontline Books. ISBN 9781783461509.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)