Yamasee War

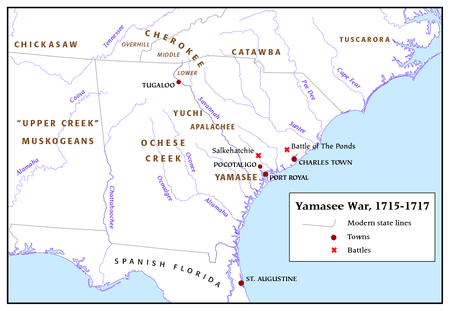

The Yamassee War was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715–1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, including the Muscogee, Cherokee, Catawba, Apalachee, Apalachicola, Yuchi, Savannah River Shawnee, Congaree, Waxhaw, Pee Dee, Cape Fear, Cheraw, and others. Some of the Native American groups played a minor role, while others launched attacks throughout South Carolina in an attempt to destroy the colony.

| Yamasee War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Colonial militia of South Carolina Colonial militia of North Carolina Colonial militia of Virginia Catawba (from 1715) Cherokee (from 1716) |

Yamasee Ochese Creeks Catawba (until 1715) Cherokee (until 1716) Waxhaw Santee | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charles Craven |

| ||||||

Native Americans killed hundreds of colonists and destroyed many settlements, and they killed traders throughout the southeastern region. Colonists abandoned the frontiers and fled to Charles Town, where starvation set in as supplies ran low. The survival of the South Carolina colony was in question during 1715. The tide turned in early 1716 when the Cherokee sided with the colonists against the Creek, their traditional enemy. The last Native American fighters withdrew from the conflict in 1717, bringing a fragile peace to the colony.

The Yamassee War was one of the most disruptive and transformational conflicts of colonial America. For more than a year, the colony faced the possibility of annihilation. About seven percent of South Carolina's settlers were killed, making the war one of the bloodiest wars in American history.[1] The Yamasee War and its aftermath shifted the geopolitical situation of both the European colonies and native groups, and contributed to the emergence of new Native American confederations, such as the Muscogee Creek and Catawba.

The origin of the war was complex, and reasons for fighting differed among the many Indian groups that participated. Factors included the trading system, trader abuses, the Indian slave trade, the depletion of deer, increasing Indian debts in contrast to increasing wealth among some colonists, the spread of rice plantation agriculture, French power in Louisiana offering an alternative to British trade, long-established Indian links to Spanish Florida, power struggles among Indian groups, and recent experiences in military collaboration among previously distant tribes.

Background

The Tuscarora War and its lengthy aftermath played a major role in the outbreak of the Yamasee War. The Tuscarora were an Iroquoian-speaking tribe of the interior, and they began attacking colonial settlements of North Carolina in 1711. South Carolina settlers mustered their militia and campaigned against the Tuscarora in 1712 and 1713. These forces were made up mainly of allied Indian troops. The Yamasee had been strong allies of South Carolina colonists for many years, and Yamasee warriors made up the core of both Carolina forces. Other Indians were recruited over a large area from diverse tribes, some of whom were traditional enemies. Tribes that sent warriors to South Carolina's militia included the Yamasee, Catawba, Yuchi, Apalachee, Cusabo, Wateree, Sugaree, Waxhaw, Congraree, Pee Dee, Cape Fear, Cheraw, Sissipahaw, Cherokee, and various proto-Creek groups.[2]

This collaboration brought Indians of the entire region into closer contact with one another. They saw the disagreements and weaknesses of the colonies, as South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia bickered over various aspects of the Tuscarora War.[3] Essentially all of the tribes that helped South Carolina during the Tuscarora War joined in attacking settlers in the colony during the Yamasee War, just two or three years later.

The Yamasee were an amalgamation of the remnants of earlier tribes and chiefdoms. The Upper Yamasee were primarily Guale originally from the Georgia coast. The Lower Yamasee included the Altamaha, Ocute (Okatee), Ichisi, (Chechessee), and Euhaw, who had come to the coast from the interior of Georgia.[4] They emerged during the 17th century in the contested frontier between South Carolina and Spanish Florida. They moved north in the late 17th century and became South Carolina's most important Indian ally. They lived near the mouth of the Savannah River and around Port Royal Sound.[5]

For years, the Yamasee profited from their relation with the settlers. By 1715, deer had become rare in Yamasee territory, and the Yamasee became increasingly indebted to the American traders who supplied them with trade goods on credit. Rice plantations had begun to thrive in South Carolina and was exported as a commodity crop, but much of the land good for rice had been taken up. The Yamasee had been granted a large land reserve on the southern borders of South Carolina, and settlers began to covet the land which they deemed ideal for rice plantations.[6]

Each of the Indian tribes that joined in the war had its own reasons, as complicated and deeply rooted in the past as that of the Yamasee. The tribes did not act in carefully planned coordination, but the unrest increased and tribes began to discuss war. By early 1715, rumors of growing Indian support for war was troubling enough that some friendly Indians warned colonists of the danger. They suggested that the Ochese Creek were the instigators.[7]

Summary of the war

Pocotaligo massacre

When the warnings about a possible Ochese Creek uprising reached the South Carolina government, they listened and acted. The government sent a party to the main Upper Yamasee town of Pocotaligo (near present-day Yemassee, South Carolina). They hoped to obtain Yamasee assistance in arranging an emergency summit with the Ochese Creek leaders. The delegation's visit to Pocotaligo triggered the start of the war.

The delegation that visited Pocotaligo consisted of Samuel Warner and William Bray, sent by the Board of Commissioners. They were joined by Thomas Nairne and John Wright, two of the most important people of South Carolina's Indian trading system. Two others, Seymour Burroughs and an unknown South Carolinian, also joined. On the evening of April 14, 1715, the day before Good Friday, the men spoke to an assembly of Yamasee. They promised to make special efforts to redress Yamasee grievances. They also said that Governor Craven was on the way to the village.

During the night, as the South Carolinians slept, the Yamasee debated over what to do. There were some who were not fully pledged to a war, but in the end the choice was made. After applying war paint, the Yamasee woke the Carolinians and attacked them. Two of the six men escaped. Seymour Burroughs fled and, although shot twice, raised an alarm in the Port Royal settlements. The Yamasee killed Nairne, Wright, Warner, and Bray. The unknown South Carolinian hid in a nearby swamp, from which he witnessed the ritual death-by-torture of Nairne.[8] The events of the early hours of Good Friday, April 15, 1715, marked the beginning of the Yamasee War.

Yamasee attacks and South Carolina counterattacks

The Yamasee quickly organized two war parties of several hundred men, which set out later in the day. One war party attacked the settlements of Port Royal, but Seymour Burroughs had managed to reach the plantation of John Barnwell and a general alarm had been raised. By chance, a captured smuggler's ship was docked at Port Royal. By the time the Yamasee arrived, several hundred settlers had found refuge on the ship, while many others had fled in canoes.

The second war party invaded Saint Bartholomew's Parish, plundering and burning plantations, taking captives, and killing over a hundred settlers and slaves. Within the week, a large Yamasee army was preparing to engage a rapidly assembled South Carolinian militia. Other Yamasee went south to find refuge in makeshift forts.

The Yamasee War was the first major test of South Carolina's militia. Governor Craven led a force of about 240 militia against the Yamasee. The Yamasee war parties had little choice but to join together to engage Craven's militia. Near the Indian town of Salkehatchie (or "Saltcatchers" in English), on the Salkehatchie River, a pitched battle was fought on open terrain. It was the kind of battle conditions which Craven and the militia officers desired and the Indians were poorly suited for.

Several hundred Yamasee warriors attacked the 240 or so members of the militia. The Yamasee tried to outflank the South Carolinians but found it difficult. After several head warriors were killed, the Yamasee abandoned the battle and dispersed into nearby swamps. Although the casualties were about equal, 24 or so on each side, the practical result was a decisive victory for South Carolina. Other smaller militia forces pressed the Yamasee and won a series of further victories.

Alexander MacKay, experienced with Indian war, led a force south. They found and attacked a group of about 200 Yamasee who had taken refuge in a palisade-fortified encampment. After a relatively small Carolinian party made two sorties over the walls of the fort, the Yamasee decided to retreat. Outside the fort, the Yamasee were ambushed and decimated by MacKay and about 100 men.

A smaller battle took place in the summer of 1715, becoming known as the Daufuskie Fight. A Carolinian boat scout crew managed to ambush a group of Yamasee, killing 35 while suffering only one casualty. Before long, the surviving Yamasee decided to move farther south to the vicinity of the Altamaha River.

Traders killed

While the Yamasee were the main concern within the colony's settlements, British traders operating throughout the southeast found they were caught up in the conflict. Most were killed. Of about 100 traders in the field when the war broke out, 90 were killed in the first few weeks. Attackers included warriors of the Creek (the Ochese, Tallapoosa, Abeika, and Alabama peoples), the Apalachee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Catawba, Cherokee, and others.

Northern Front

During the first month of the war, South Carolina hoped to receive assistance from the northern Indians, such as the Catawba. But the first news from the north was that the Catawba and Cherokee had murdered British traders among them. The Catawba and Cherokee had not attacked traders as quickly as did the southern Indians. Both tribes were divided over what course to take. Some Virginian traders were accused of goading the Catawba into making war on South Carolina. Although the Catawba killed traders from South Carolina, they spared those from Virginia.

By May 1715 the Catawba sent war parties against South Carolina settlers. About 400 warriors from the Catawba, Wateree, and Sarraw tribes, joined by about 70 Cherokee, terrorized the northern parts of the colony. The Anglican missionary Francis Le Jau stated that on May 15th South Carolinian force of 90 cavalry under Captain Thomas Barker, many of them Le Jau's parishioners, went north in response. They were guided by a former Native American slave who had been freed by Captain Barker's father-in-law Col. Jame Moore. Le Jau was of the opinion that the freed slave named Wateree Jack[9] purposefully led Barker and his men into an ambush on May 17, laid by a force that he said contained a "Body of Northern Indians being a mixture of Catabaws, Sarraws Waterees &c. to Number of 3. or 400".[10] In the ambush the Northern Indian war party managed to kill 26 of them including Barker, ten of which were Le Jau's parishioners.. The defeat of Barker prompted the evacuation of the Goose Creek settlement leaving it entirely abandoned but for two fortified plantations.[11] Le Jau noted that, rather than press their advantage, the Northern Indian war band stopped to besiege a makeshift fort on Benjamin Schenkingh's plantation. The fort was garrisoned by 30 defenders, both white and black. Ultimately the attackers feigned a desire to have peace talks. When they were allowed in they set about killing 19 of the defenders. After this, South Carolina had no defenses for the wealthy Goose Creek district, just north of Charles Town.

Before the northern forces attacked Charles Town, most of the Cherokee left, as they had heard about their own towns being threatened. The remaining Northern Indians then faced a rapidly assembled militia of 70 men under the command of George Chicken, Le Jau's own son being among them. On June 13, 1715, Chicken's militia ambushed a Catawba party and launched a direct assault upon the main Catawba force. In the Battle of the Ponds, the militia routed the Catawba. The warriors were not used to such direct confrontation. After returning to their villages, the Catawba decided on peace. By July 1715, Catawba diplomats arrived in Virginia to inform the British of their willingness to not only make peace, but to assist South Carolina militarily.

Creek and Cherokee

The Ochese Indians had probably been instigators of the war at least as much as the Yamasee. When the war broke out, they promptly killed all the South Carolinian traders in their territory, as did the other Creek, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee.

The Ochese Creek were buffered from South Carolina by several smaller Indian groups, such as the Yuchi, Savannah River Shawnee, Apalachee, and Apalachicola. In the summer of 1715, these Indians made several successful attacks on South Carolina settlements. Generally the Ochese Creek were cautious after South Carolina's counterattacks proved effective. The smaller Indian groups fled the Savannah River area.

Many found refuge among the Ochese Creeks, where plans were being made for the next stage of the war. The Upper Creek were not as determined to wage war had strong respect for the Ochese Creek. They might have joined in an invasion if conditions were favorable. An issue at stake was trade goods. The Creek people had come to depend on English trade goods from South Carolina. Facing possible war with the British, the Creek looked to the French and Spanish as possible market sources. The French and Spanish were more than willing to supply the Creek, but they were unable to provide the same quantity or quality of goods which the British had been providing. Muskets, gunpowder, and bullets were especially needed if the Creek were to invade South Carolina. The Upper Creek remained reluctant to go to war. Nevertheless, the Creek formed closer ties to the French and Spanish during the Yamasee War.

The Ochese Creeks had other connections, such as the Chickasaw and Cherokee. But the Chickasaw, after killing their English traders, had been quick to make peace with South Carolina. They blamed the deaths of the traders in their towns on the Creeks—a lame excuse that was gladly accepted by South Carolina. The Cherokee's position became strategically important.

The Cherokee were divided. In general the Lower Cherokee, who lived closest to South Carolina, tended to support the war. Some participated in Catawba attacks on South Carolina's Santee River settlements. The Overhill Cherokee, who lived farthest from South Carolina, tended to support an alliance with South Carolina and war against the Creek. One of the Cherokee leaders most in favor of an alliance with South Carolina was Caesar, a chief of a Middle Cherokee town.

In late 1715, two South Carolinian traders visited the Cherokee and returned to Charles Town with a large Cherokee delegation. An alliance was made, and plans for war against the Creek developed. But in the following month the Cherokee failed to meet up with South Carolinians at Savannah Town as planned. South Carolina then sent an expedition of over 300 soldiers to the Cherokee, arriving in December, 1715. They split up and visited the key Lower, Middle, and Overhill towns, and quickly saw how divided the Cherokee were. During the winter the Cherokee leader Caesar traveled throughout the Cherokee towns, drumming up support for war against the Creek. Other prestigious and respected Cherokee leaders urged caution and patience, including Charitey Hagey the Conjurer of Tugaloo, one of the Lower Towns closest to South Carolina. Many of the Lower Town Cherokee were open to peace with South Carolina, but reluctant to fight anyone other than the Yuchi and Savannah River Shawnee.

The South Carolinians were told that a "flag of truce" had been sent from the Lower Towns to the Creek, and that a delegation of Creek headmen had promised to come. Charitey Hagey and his supporters seemed to be offering to broker peace talks between the Creek and South Carolinians. They convinced the South Carolinians to alter their plans of war. Instead, the South Carolinians spent the winter trying to dissuade Caesar and the pro-war Cherokee.

Tugaloo Massacre

On January 27, 1716, the South Carolinians were summoned to Tugaloo, where they discovered that the Creek delegation had arrived and that the Cherokee had killed 11 or 12 of them. The Cherokee claimed that the Creek delegation was in fact a war party of hundreds of Creek and Yamasee, and that they had nearly succeeded in ambushing the South Carolinian forces. It remains unknown exactly what happened at Tugaloo. That the Cherokee and Creek met in private without the South Carolinians present suggests that the Cherokee were still divided on whether to join the Creek and attack South Carolina or join the South Carolinians and attack the Creek. It is possible that the Cherokee, who were relatively new to trade with the British, hoped to replace the Creek as South Carolina's main trading partner. Whatever the underlying factors, the murders at Tugaloo probably resulted from an unpredictable and heated debate which, like the Pocotaligo massacre, ended in an impasse resolved through murder. After the Tugaloo massacre the only possible solution was war between the Cherokee and Creek and an alliance between the Cherokee and South Carolina.

The Cherokee alliance with South Carolina doomed the possibility of a major Creek invasion of South Carolina. At the same time, South Carolina was eager to regain peaceful relations with the Creek and did not want to fight a war with them. While South Carolina did supply the Cherokee with weapons and trade goods, they did not provide the military support that the pro-war Cherokee had hoped for. There were Cherokee victories in 1716 and 1717, but Creek counterattacks undermined the Cherokee's will to fight, which had been divided from the start. Nevertheless, the Creek and Cherokee continued to launch small-scale raids against each other for generations.

In response to The Tugaloo massacre and the Cherokee attacks, the Ochese Creek made a strategic defensive adjustment in early 1716. They relocated all their towns from the Ocmulgee River basin to the Chattahoochee River. The Ochese Creek had originally lived along the Chattahoochee, but had moved their towns to the Ocmulgee River and its tributary, Ochese Creek (from which the name "Creek" came), around 1690, in order to be closer to South Carolina. Their return to the Chattahoochee River in 1716 was thus not so much a retreat as a return to previous conditions. The distance between the Chattahoochee and Charles Town protected them from a possible South Carolina attack.

In 1716 and 1717, as no major Cherokee-British attack materialized, the Lower Creek found themselves in a position of increased power and resumed raiding their enemies—British, Cherokee, and Catawba. But, cut off from British trade, they began to experience problems in the supply of ammunition, gunpowder, and firearms. The Cherokee, on the other hand, were well-supplied with British weaponry. The lure of British trade undermined anti-British elements among the Creek. In early 1717 a few emissaries from Charles Town went to the Lower Creek territory, and a few Creek went to Charles Town, tentatively starting the process that would lead to peace. At the same time other Lower Creeks were looking for ways to continue to fight. In late 1716 a group representing many Muskogean Creek nations traveled all the way to the Iroquois Six Nations in New York. Impressed by the Creek's diplomacy, the Iroquois sent 20 of their own ambassadors to accompany the Creek back home. The Iroquois and Creek were mainly interested in planning attacks on their mutual Indian enemies, like the Catawba and Cherokee. But to South Carolina, a Creek-Iroquois alliance was something to be avoided at all costs. In response, South Carolina sent a group of emissaries to the Lower Creek towns, along with a large cargo of trade good presents.

Frontier insecurity

After the Yamasee and Catawba had pulled back, South Carolina's militia reoccupied abandoned settlements and tried to secure the frontier, turning a number of plantation houses into makeshift forts. The militia had done well in preemptive offensive fighting, but was unable to defend the colony against raiding parties. Members of the militia began to desert in large numbers during the summer of 1715. Some were concerned for their own property and families, while others simply left South Carolina altogether.

In response to the militia's failure, Governor Craven replaced it with a professional army (that is, an army whose soldiers were paid). By August 1715 South Carolina's new army contained about 600 South Carolinian citizens, 400 black slaves, 170 friendly Indians, and 300 troops from North Carolina and Virginia. This was the first time the South Carolina militia had been disbanded and a professional army assembled. It is also notable for the high number of black slaves armed (and their masters paid) to wage war.

But even this army was not able to secure the colony. The hostile Indians simply refused to engage in pitched battles, using unpredictable raids and ambushes instead. In addition, the Indians occupied such a large territory that it was effectively impossible to send an army against them. The army was disbanded after the Cherokee alliance was established in early 1716.

Resolution

Since so many different tribes were involved in the war, with varying and changing participation, there was no single definitive end to the conflict. In some respects the main crisis was over within a month or two. The Lords Proprietors of the colony believed the colony was no longer in mortal danger after the first few weeks. For others it was the Cherokee alliance of early 1716 that marked the end of the war. Peace treaties were established with various Creek and other Muskogean peoples in late 1717. But some tribes never agreed to peace, and all remained armed. The Yamasee and Apalachicola had moved south, but continued to raid South Carolina's settlements well into the 1720s. Frontier insecurity remained a problem.

Consequences

Political change

Although it took several years to accomplish, the Yamasee War led directly to South Carolina's overthrow of the Lords Proprietors. By 1720 the process of transition from a proprietary colony to a crown colony had begun. It took nine years, but in 1729 South Carolina and North Carolina officially became crown colonies. South Carolinians had been discontented with the proprietary system before the Yamasee War, but the call for change became shrill in 1715, after the first phase of the war, and only grew louder in the following years.[12]

The Yamasee War also led to the establishment of the colony of Georgia. While there were other factors involved in Georgia's founding, it would not have been possible without the withdrawal of the Yamasee. The few Yamasee that remained became known as the Yamacraw. James Oglethorpe negotiated with the Yamacraw in order to obtain the site where he founded his capital city of Savannah.[13]

Indian aftermath

In the first year of the war the Yamasee lost about a quarter of their population, either killed or enslaved. The survivors moved south to the Altamaha River, a region that had been their homeland in the 17th century. But they were unable to find security there and soon became refugees. As a people, the Yamasee had always been ethnically mixed, and in the aftermath of the Yamasee War they split apart. About a third of the survivors chose to settle among the Lower Creek, eventually becoming part of the emerging Creek confederacy. Most of the rest, joined by Apalachicola refugees moved to the vicinity of St. Augustine in the summer of 1715. Despite several attempts to make peace, by both South Carolinians and Yamasee individuals, conflict between the two continued for decades. The Yamasee of Spanish Florida were in time weakened by disease and other factors. The survivors either became part of the Seminole or the Hitchiti.

The various proto-Creek Muskogean tribes grew closer after the Yamasee War. The reoccupation of the Chattahoochee River by the Ochese Creek, along with remnants of the Apalachicola, Apalachee, Yamasee, and others, seemed to Europeans to represent a new Indian identity, and needed a new name. To the Spanish it seemed like a reincarnation of the Apalachicola Province of the 17th century. To the English, the term Lower Creek became common.

The Catawba confederacy emerged from the Yamasee War as the most powerful Indian force of the Piedmont region, especially as the Tuscarora migrated away to join the Iroquois in the north. In 1716, a year after the Catawba had made peace with South Carolina, some Santee and Waxhaw Indians killed several colonists. In response the South Carolina government asked the Catawba to "fall upon them and cut them off", which the Catawba did. According to contemporaries, surviving Waxhaw then either joined the Cheraw or traveled south to Florida with the Yamasee.[14] There is another theory, originating with Robert Ney McNeely's history of Union County, published in 1912, that the Waxhaw continued on as an independent tribe until the 1740s but this seems to lack the backing of primary sources. Surviving Santee are reported to have married into the Ittiwan tribe[15] suggesting a possible merger. The Cheraw remained generally hostile for years to come.

In popular culture

In 1904 Annie Barnes novel "The Laurel Token: A Story of the Yamasee War" was published.[16]

See also

- American Indian Wars

- Colonial period of South Carolina

- Fort Frederick Heritage Preserve, Port Royal

- List of conflicts in British America and North America prior to 1783

- List of conflicts in the United States

- Timeline of United States history

- Tuscarora War

- Wars of the indigenous peoples of North America

References

Citations

- Oatis, A Colonial Complex, p. 167.

- Galley, The Indian Slave Trade, 267–268, 283.

- Galley, The Indian Slave Trade, 276–277.

- Worth 1993:40–45

- "The Foundation, Occupation, and Abandonment of Yamasee Indian Towns in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1684-1715", National Register Multiple Property Submission, Dr. Chester B. DePratter, National Park Service

- Gallay, Alan (2003). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717. Yale University Press. pp. 218, 330–331. ISBN 978-0-300-10193-5.

- Oatis, Steven J. (2004). A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680-1730. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 0-8032-3575-5.

- Oatis, A Colonial Complex, 124–125.

- Heitzler, Michael (2012). The Goose Creek Bridge: Gateway to Sacred Places. Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse. pp. 64–66. ISBN 1477255389.

- Le Jau, Francis (1956). The Carolina Chronicle of Dr. Francis Le Jau. Berkeley, CA: University of California. pp. 160–163.

- Le Jau, Francis (1956). The Carolina Chronicle of Dr. Francis Le Jau. Berkeley: University of California. pp. 158–159.

- Oatis, A Colonial Complex, 165–166.

- Oatis, A Colonial Complex, 288–291.

- Moore, P.N. (2007)World of Toil and Strife, p.16

- Hicks, T. M (1998). South Carolina Indians, Indian traders, and other ethnic connections beginning in 1670. Spartanburg, South Carolina: Reprint Company Publishers.

- Barnes, Annie Maria (3 June 2018). "The laurel token; a story of the Yamasee uprising". Boston, Lee and Shepard – via Internet Archive.

Bibliography

- Ramsey, William L. (2008). The Yamasee War: A Study of Culture, Economy, and Conflict in the Colonial South. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3744-5.

- Gallay, Alan (2002). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10193-5.

- Oatis, Steven J. (2004). A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680-1730. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-3575-5.

- Worth, John (1993). "Prelude to Abandonment: The Interior Provinces of Early 17th-Century Georgia". Early Georgia: Journal of the Society for Georgia Archaeology. 21. pp. 24–58..

Further reading

| Library resources about Yamasee War |

- Crane, Verner (1928). The Southern Frontier, 1670-1732. Duke University Press.

- Stern, Jessica Ross (2009). "The Yamasee War: A Study of Culture, Economy, and Conflict in the Colonial South (review)." Journal of Interdisciplinary History 39.4 : 594-595. Project MUSE. Web. 25 Jan. 2013.

External links

- History Cooperative, William L. Ramsey, "Something Butty in Their Looks": The Origins of the Yamasee War Reconsidered The Journal of American History.

- Yamassee War of 1715, Our Georgia History.

- South Carolina Forts; Yamasee War era forts include Willtown Fort, Passage Fort, Saltcatchers Fort, Fort Moore, and Benjamin Schenckingh's Fort.

- Appalachian Summit, Chapter 4: Dear Skins Furrs and Younge Indian Slaves, transcriptions of primary source letters regarding the Cherokee during the Yamasee War era.