Invasion of Ceylon (1795)

The Invasion of Ceylon was a military campaign fought as a series of amphibious operations between the summer of 1795 and spring of 1796 between the garrison of the Batavian colonies on the Indian Ocean island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and a British invasion force sent from British India. The Dutch Republic had been a British ally during the French Revolutionary Wars, but was overrun by the French Republic in the winter of 1794 and reformed into the client state of the Batavian Republic. The British government, working with the exiled Stadtholder William of Orange, ordered the seizure of Batavian assets including colonies of the former Dutch Empire. Among the first territories to be attacked were those on the coast of the island of Ceylon, with operations initially focused on the trading port at Trincomalee.

To achieve the seizure of the colony, the British government instructed Lord Hobart, Governor of Madras to use the forces at his disposal to invade and capture the Batavian-held parts of the island. Prosecution of the campaign was given to Colonel James Stuart, supported by naval forces under Rear-Admiral Peter Rainier. Stuart called on Batavian governor Johan Van Angelbeek to surrender the colony peacefully and many trading posts were taken without resistance, but Stuart's forces were opposed at Trincomalee in August 1795 and briefly at Colombo in February 1796. Following short sieges British forces were able to secure control of the Dutch colony, and Ceylon would remain a part of the British Empire for the next 153 years.

Background

In 1793, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic went to war with the French Republic, joining the ongoing French Revolutionary Wars. Despite resistance from the Dutch Army and a British expeditionary force, the Dutch Republic was overrun by the French in the winter of 1794–1795, the French reforming the country into the Batavian Republic, a client state of the French regime.[1] Although war between Britain and the Batavian Republic had not been declared, the British government sent instructions on 19 January for Batavian shipping to be seized and, in conjunction with Stadtholder William of Orange, living in exile in London, for Batavian colonies to be neutralised in order to deny their use to the French. On 9 February these orders culminated in the outbreak of war between Britain and the Batavian Republic.[2]

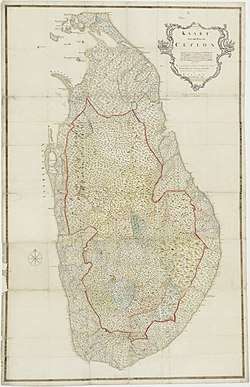

News of the conflict took some months to reach the East Indies, where British and French naval forces had fought an inconclusive campaign for control of the Indian Ocean trade routes since 1793. British forces, supporting those of the East India Company, were principally operating from Madras and Calcutta in India, the French from their island bases of Île de France (now Mauritius) and Réunion.[3] Following an inconclusive engagement off Île Ronde on 22 October 1794, the French squadron on Île de France had remained under blockade at Port Louis and thus most of the British naval forces in the East Indies were available for the campaign against the Batavian territories.[4] Dutch colonisation of Ceylon did not span the whole island, which was mostly ruled by the interior Kingdom of Kandy. European settlement was instead concentrated at coastal strips surrounding the significant ports of Colombo on the west coast and Trincomalee on the east, supplemented by smaller trading factories and settlements elsewhere.[5] Trincomalee was particularly important as raiding forces based in the port could easily strike against British trade routes in the Bay of Bengal, but the port had limited food supplies, poorly-developed facilities and a small garrison.[5]

Planning

Upon receiving the news of the hostilities between Britain and the Batavian Republic, Lord Hobart, Governor of Madras, conferred with Rainier and ordered the invasion of Ceylon.[4] Command of land forces was given to Colonel James Stuart, whose forces consisted of the 71st, 72nd and 73rd Regiments of Foot, 1st and 23rd battalions Madras Native Infantry and detachments from the Royal Artillery and Madras Artillery and auxiliary forces, totaling 2,700 men.[6] This force was supported by a Royal Navy force led by Rainier in the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Suffolk and the 50-gun fourth rate ship HMS Centurion, which sailed from Madras on 21 July. Suffolk escorted a large convoy of East India Company merchant ships transporting troops and supplies, augmented off Negapatnam by additional reinforcements protected by the frigates HMS Diomede and HMS Heroine.[7]

It was hoped by Stuart and Rainer that the Batavian governor Johan Van Angelbeek might be persuaded to allow a peaceful occupation of Ceylon by British forces, especially in light of the Kew Letters from William of Orange, which advocated cooperation with British forces.[8] A Major Agnew was sent ashore at Colombo to negotiate and his attempts to persuade Van Angelbeek to allow 300 British troops to land at Fort Oostenberg, which overlooked Trincomalee, were successful.[9] On arrival off the port on the eastern coast of Ceylon on 1 August however the commander of the defences refused to acknowledge the instruction, citing problems with the wording of the instructions.[10] For two days attempts were made to convince the Batavian commander, the British position partially undermined by the destruction of Diomede in Trincomalee harbour after striking an uncharted rock. Although all of the crew and passengers were saved, large quantities of military stores sank with the frigate.[11]

Invasion

Siege of Trincomalee

On 3 August, with negotiations fruitless, Rainier and Stuart ordered the invasion to go ahead. The troops landed 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) north of Trincomaleee unopposed and advanced slowly though the sandy terrain. Due to heavy surf and high winds the disembarkation was not completed until 13 August, and the first emplacements approaching Trincomalee were not begun until 18 August.[11] Throughout this period the Batavian garrison made no effort to oppose or impede the advance British forces. After five days the British forces had emplaced eight 18-pounder long guns and a number of smaller cannon, some borrowed from Suffolk in firing positions, opening a heavy fusilade which by the following day had created a sizeable breach in the walls of Trincomalee. Preparations were made for an assault and messages sent to the fort's commander demanding his surrender.[12]

After some negotiation followed by a brief resumption of the bombardment, the Batavian commander surrendered. The garrison of 679 troops were taken prisoner and more than 100 cannon seized by the British. British losses in the brief campaign amounted to 16 killed and 60 wounded.[11] Following the fall of Trincomalee, nearby Fort Oostenberg was summoned to surrender on 27 August.[10] Four days later the commander turned his position over to the British under the same terms offered to the garrison of Trincomalee. With resistance broken, Batavian trading posts along the Ceylon coastline surrendered in quick succession, Batticaloa to the 22nd Regiment of Foot on 18 September, Jaffna to Stuart directly on 27 September after a landing in force, Mullaitivu to a detachment of troops from 52nd Regiment of Foot in HMS Hobart on 1 October, and the island of Mannar on 5 October.[13]

Fall of Colombo

In September 1795, Rainier took most of his squadron eastwards to operate against Batavia, leaving Captain Alan Gardner in command of the blockade of Colombo, the last remaining Batavian territory on the island. In January 1796, command of the East Indies was assumed by Sir George Keith Elphinstone, who ordered ships of the line HMS Stately and HMS Arrogant to assist Gardner.[14]

In February 1796 a final expedition was prepared against Ceylon, with instructions to seize Colombo and the surrounding area. Stuart again took command, supported by Gardner in Heroine and the sloops HMS Rattlesnake, HMS Echo and HMS Swift, as well as five EIC ships.[15] Stuart's force disembarked at Negombo, a Dutch fort abandoned the previous year, on 5 February and marched overland to Colombo, arriving without opposition on 14 February. The garrison was issued with a demand requiring their surrender or to expect an immediate assault, and storming parties were prepared, but on 15 February Van Angelbeek agreed to capitulate and Stuart took possession of the city peacefully.[16]

Aftermath

The value of the captured goods from Colombo alone amounted to more than £300,000.[16] More importantly for the British, Ceylon was not one of the colonies returned to the Batavian Republic following the Treaty of Amiens which brought the war to a brief close in 1802.[17] Britain retained Ceylon as part of the British Empire until independence was granted in 1948.

Notes

- Chandler, p. 44.

- Woodman, p. 53.

- Parkinson, p. 74.

- Parkinson, p. 77.

- Parkinson, p. 35.

- "Under a Tropical Sun". Macquarie University. 2011. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- James, p. 302.

- Parkinson, p. 78.

- "No. 13852". The London Gazette. 8 January 1796. p. 33.

- Parkinson, p. 80.

- James, p. 303.

- Clowes, p. 282.

- James, p. 304.

- Parkinson, p. 84.

- Clowes, p. 294.

- James, p. 371.

- Chandler, p. 10.

References

- Chandler, David (1999) [1993]. Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-203-4.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 1, 1793–1796. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-905-0.

- Parkinson, C. Northcote (1954). War in the Eastern Seas, 1793 - 1815. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.