Asiento de Negros

The asiento was a short-term loan or debt contract, of about one to four years, signed between the Spanish crown and a banker or a small group of bankers ("asentistas") against future crown revenues,[1][2] and included after peace treaties were signed. Between the early 16th and the mid-18th century, asientos were used by the Spanish treasurer to adjust short-term imbalances between revenues and expenditures. The sovereign promised to repay the principal of the loan plus high interest. The participant bankers in Seville, Lisbon, Genoa and Amsterdam, in turn, drew on the profits and direct investments obtained from a large number of Atlantic merchants.[3] In exchange for a set of scheduled payments, merchants and financiers were given the right to collect relevant taxes or oversee the trade in those commodities that fell under the monarch's prerogative. In this way a set of merchants received the right to ship tobacco, salt, sugar and cacao on a trade route from the Spanish West Indies, some times accompanied by licenses to export bullion from Spanish Main or Cadiz.[4] In particular, the asiento would result in great impact for the economy of Spanish American colonies, because the treaty secured or would secure fixed revenues for the crown and the supply of the region with certain commodities, whereas the contracting party bore the risk of the trade.[5] A new asiento was the safest means to get their money back and cash their arrears.[6]

A specific example, the Asiento de Negros, was the right to import and sell a fixed number of enslaved Africans in Spanish America. They were usually obtained by foreign merchant banks, in the beginning by Portuguese and Genovese, and later by Dutch, French and English, who cooperated with local or foreign traders, specialized in shipping. The asiento specified the places of importation and the points of delivery, as well as navigation routes.

The original impetus to import enslaved Africans was to relieve the indigenous inhabitants of the colonies from the labor demands of the Spanish colonists.[7] Spain gave individual asientos to Portuguese merchants to bring slaves to South America. In 1575 the decree of bankruptcy ruined almost all the Spanish "asentistas". From 1577 until the bankruptcy of 1627, Genovese bankers played a mayor role in financing Spanish imperialism.[8] Most Portuguese contractors who obtained the asiento between 1580 and 1640 were conversos.[9] The first major Asiento involving Portuguese financiers was concluded in 1625 and before 1647 they provided roughly half of the Asientos made in Spain for the Netherlands.[10]

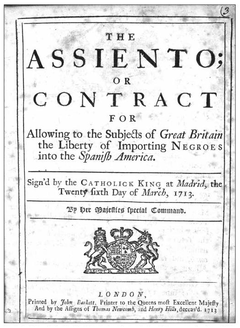

After the Treaty of Münster, Dutch merchants became involved in the Asiento de Negros. In 1713, the British were awarded the right to the asiento in the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession. The British government passed its rights to the South Sea Company.[11] The British asiento ended with the 1750 Treaty of Madrid between Great Britain and Spain.

History of the Asiento

Background in the Spanish Americas

The general meaning of asiento (from the Spanish verb sentar, to sit, which was derived from the Latin sedere) in Spanish is "consent" or "settlement, establishment". In a commercial context it means "contract, trading agreement". In the words of Georges Scelle, it was "a term in Spanish public law which designates every contract made for the purpose of public utility...between the Spanish government and private individuals."[12]

The asiento system was established following Spanish settlement in the Caribbean, when the indigenous population was undergoing demographic collapse and the Spanish needed another source of labor. Initially a few Christian Africans born in Iberia were transported to the Caribbean. But as the indigenous demographic collapse was ongoing and opponents of Spanish exploitation of indigenous labor grew, including that of Bartolomé de Las Casas, the young Habsburg king Charles I of Spain allowed for the direct importation of slaves from Africa (bozales) to the Caribbean. The first asiento for selling slaves was drawn up in August 1518, granting a Flemish favorite of Charles, es:Laurent de Gouvenot, a monopoly on importing enslaved Africans for eight years with a maximum of 4,000. Gouvenot promptly sold his license to the treasurer of the Casa de la Contratación de Indias and three subcontractors, Genoese merchants in Andalusia, for 25,000 ducats.[13][14] The Casa de Contratación in Seville controlled both trade and immigration to the New World, excluding Jews, conversos, Muslims, and foreigners. African slaves were considered merchandise, and their import regulated by the crown.[15] The Spanish crown collected a duty on each "pieza", and not on each individual slave delivered.[16] Spain had neither direct access to the African sources of slaves nor the ability to transport them, so the asiento system was a way to ensure a legal supply of Africans to the New World, which brought revenue to the Spanish crown.[17]

Portuguese and Sephardic monopoly

For the Spanish crown, the asiento was a source of profit. Haring says, "The asiento remained the settled policy of the Spanish government for controlling and profiting from the slave trade."[11] In Habsburg Spain, asientos were a basic method of financing state expenditures: "Borrowing took two forms – long-term debt in the form of perpetual bonds (juros), and short-term loan contracts provided by bankers (asientos). Many asientos were eventually converted or refinanced through juros."[18]

Initially, since Portugal had unimpeded rights in West Africa via its 1494 treaty it dominated the European slave trade of Africans. Before the onset of the official asiento in 1595, when the Spanish monarch also ruled Portugal in the Iberian Union (1580–1640), the Spanish fiscal authorities gave individual asientos to merchants, primarily from Portugal, to bring slaves to the Americas. For the 1560s most of these slaves were obtained in the Upper Guinea area, especially in the Sierra Leone region where there were many wars associated with the Mandé invasions.

Following the establishment of the Portuguese colony of Angola in 1575, and the gradual replacement of São Tomé by Brazil as the primary producer of sugar, Angolan interests came to dominate the trade, and it was Portuguese financiers and merchants who obtained the larger-scale, comprehensive asiento that was established in 1595 during the period of the Iberian Union. The asiento was extended to importation of African slaves to Brazil, with those holding asientos for the Brazilian slave trade often also trading slaves in Spanish America. Spanish America was a major market for African slaves, including many of whom exceeded the quota of the asiento license and illegally sold. Till 1622 half of the slaves were destined for Mexico.[19] Most smuggled slaves were not brought by freelance traders.[20]

Angolan dominance of the trade was pronounced after 1615 when the governors of Angola, starting with Bento Banha Cardoso, made alliance with Imbangala mercenaries to wreak havoc on the local African powers. Many of these governors also held the contract of Angola as well as the asiento, thus insuring their interests. Shipping registers from Vera Cruz and Cartagena show that as many as 85% of the slaves arriving in Spanish ports were from Angola, brought by Portuguese ships. In 1637 the Dutch West India Company employed Portuguese merchants in the trade.[21] The earlier asiento period came to an end in 1640 when Portugal revolted against Spain, though even then the Portuguese continued to supply Spanish colonies.

Dutch, French and British competition

In the 1650s after Portugal achieved its independence from Spain, Spain denied the asiento to the Portuguese, whom it considered rebels.[22] Spain sought to enter the slave trade directly, sending ships to Angola to purchase slaves. It also toyed with the idea of a military alliance with Kongo, the powerful African kingdom north of Angola. But these ideas were abandoned and the Spanish returned to Portuguese and then Dutch interests to supply slaves. The Spanish awarded large contracts for the asiento to the Dutch West India Company in 1675 rather than Portuguese merchants in the 1670s and 1680s.[23] However, this same time period saw a resurgence of piracy in the Caribbean due to the growth of the slave trade. In 1700, with the death of the last Habsburg monarch, Charles II of Spain, his will named the House of Bourbon in the form of Philip V of Spain as the successor to the Spanish throne. The Bourbon family were also Kings of France and so the asiento was granted in 1702 to the French Guinea Company, for the importation of 48,000 African slaves over a decade. The Africans were transported to French Caribbean colonies of Martinique and Saint Domingue.

As part of their strategy of maintaining a balance of power in Europe, Great Britain and her allies, including the Dutch and the Portuguese, disputed the Bourbon inheritance of the Spanish throne and fought in the War of the Spanish Succession against Bourbon hegemony. Although Britain did not prevail, it did receive the asiento as part of the Peace of Utrecht.[nb 1] This granted Britain a thirty-year asiento to send one merchant ship to the Spanish port of Portobelo, furnishing 4800 slaves to the Spanish colonies. The asiento became a conduit for British contraband and smugglers of all kinds, which undermined Spain's attempts to keep a protectionist trading system with its American colonies.[24] Disputes connected with it led to the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739).[25] Britain gave up its rights to the asiento after the war, in the Treaty of Madrid of 1750, as Spain was implementing a number of administrative and economic reforms. The Spanish Crown bought out the South Sea Company's right to the asiento that year. The Spanish Crown sought another way to supply African slaves, attempting to liberalize its traffic, trying to shift to a system of the free trade in slaves by Spaniards and foreigners in particular colonial locations. These were Cuba, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, and Caracas, all of which used African slaves in large numbers.[26]

Holders of the Asiento

Early: 1518–1595

- 1518–1527: Laurent de Gouvenot (aka Lorenzo de Gorrevod or Garrebod), Governor of Bresse and majordomo of Charles I of Spain.[27][28] The first known transatlantic slave ship—sailed from São Tomé in 1525.

- Outsourced to Domingo de Forne, Agustín de Ribaldo and Fernando Vázquez, all Genoese established in Seville.[28]

- 1528–1536: The Welser and Fugger family from Augsburg.[29] The opening for the Genovese banking consortium was the state bankruptcy of Philip II in 1557, which threw the German banking houses into chaos and ended the reign of the Fuggers as Spanish financiers. The Genovese bankers provided the unwieldy Habsburg system with fluid credit and a dependably regular income. In return the less dependable shipments of American silver were rapidly transferred from Seville to Genoa, to provide capital for further ventures.

- 1536–1595: Liberalization.[29]

Portuguese: 1595–1640

Six Asientos were granted to:

- 30 January 1595 – 13 May 1601: Pedro Gomes Reynel[30][nb 2][31][32] Slaves could be transported in ships unconnected to the Spanish treasure fleet system, but only with Portuguese or Castilian crews, and with the obligation "not to trade in the Indies".[33]

- 13 May 1601 – 16 October 1604:[30] João Rodrigues Coutinho. Soon after the annulment of Reynel's contract, a new asiento was let to Coutinho, governor of Angola and holder of the royal tax-farming contract there. The terms of the agreement were much stricter, and Coutinho ran almost immediately into legal and financial difficulties.[34]

- 16 October 1604 – 27 September 1615:[30] Gonçalo Vaz Coutinho

- 27 September 1615 – 1 April 1623:[30] António Fernandes de Elvas. The two main places in the Spanish Americas that slaves were brought were Cartagena de Indias (in modern Colombia) and Veracruz (in modern Mexico)[35] from here they were distributed out towards what is today Venezuela, the Antilles and Lima (through Portobello and Panama) then to Upper Peru and Potosí.

- 1 April 1623 – 25 September 1631:[30] Manuel Rodrigues Lamego; 59 ships were licenced for Africa, where around 8,000 African slaves were purchased from West African merchants, mostly from Luanda.[36]

- 25 September 1631 – 1 December 1640:[30] Melchor Gómez Angel and Cristóvão Mendes de Sousa.

Between 1640–1651 there was no asiento.[37] Slave arrivals to the Spanish Americas declined precipitously.[38] The Dutch were expelled from Loango-Angola in 1648. Dutch private entrepreneurs were responsible for almost half of the total investment in slave trade against a smaller share held by the WIC.[39] In 1649 the Swedish Africa Company was founded by Louis De Geer. In March 1659 the Danish Africa Company was started by the Finnish Hendrik Carloff and two Dutchmen. Their mandate included trade with the Danish Gold Coast. Their goal was to compete with the Dutch, the Swedish and the Portuguese. The Dutch competed with the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa founded in 1660. Both of these slaving powers had a strong presence on the Gold Coast (British colony) and the Bight of Benin; many slaves came from Cross River (Nigeria) in the Bight of Biafra and West Central Africa. Matthias Beck, who had left Dutch Brazil in 1654, was appointed by the WIC as governor of Curaçao, that, from 1662 to 1728 and intermittently thereafter, functioned as an entrepôt through which captives on Dutch transatlantic ships reached Spanish colonies. A second branch of the intra-American slave traffic originated in Barbados and Jamaica.[40]

Genoese: 1662–1671

In 1658 Ambrogio Lomellini and Domingo Grillo were appointed as Treasurers of the Holy Crusade, waging war against "infidels". This fact allowed them to have access to a part of the treasures that came from America.[41] (From the late 1640's Grillo and his business partner Lomellini lived in Madrid.[42]) In 1662 and 1666 Spain went bankrupt.[43] Slave-contracts of the WIC with Grillo and Lomelino (Lomellini) of Madrid, 1662 and 1667,[44][45] who were given permission to sub-contract to any nation friendly to Spain.

- July 5, 1662 – 1669: Grillo and Lomellini promised to ship 24,000 slaves in seven years, assisted by the Dutch West India Company and the English Royal Adventurers from Jamaica and Curaçao to Cartagena, Colombia, Veracruz in Mexico and Portobello in Panama.[46] English dealers would now compete with the Dutch for this Spanish trade in slaves. In 1664, the political situation in Europe and the Caribbean was volatile. Grillo and Lomellini contacted nl:Francesco Ferroni in Amsterdam and then turned to the Dutch in order to complete to the conditions of their contract.[47][48] Grillo's monopoly was bitterly received in the colonies. He operated almost exclusively by proxy.[49] In 1668 when Grillo's estate was threatened to be confiscated because of enormous debts, he succeeded in an extension of the Asiento for two years.

- In 1668 an immense warehouse was erected on Curaçao.[50] About 90% of the slaves were exported from Curacao and half of them illegally.[51][52]

- In 1669 Spain is almost bankrupt. The Coymans bank in Amsterdam transported on four warships from New Spain Spanish dollars or bars of silver (worth 500,000 guilders) to Cadiz in order to get a subcontract.[53] Also the Catholic King Charles II of England tried to acquire the asiento.[54]

- In 1670 England gained formal possession of Jamaica from Spain through the Treaty of Madrid.

- In 1671 the Grillo asiento is ended because of mistrust.[55][56] As the Grillos drew on markets within the Americas to meet their asiento commitments, commercial networks and distribution routes changed – direct voyages from Africa to Spanish America became uncommon, whereas Jamaica, Barbados, and Curaçao became the busiest slave trade depots in the Caribbean.[57][58] Grillo's experience opened up the way for expansion of the Dutch, English and French slave trading companies.[59]

- In 1672 the Royal Africa Company was founded.

- In 1673 the Compagnie du Sénégal was founded, and used Gorée to house the slaves since 1677. According to historical accounts, no more than 500 slaves per year were traded there.[60]

- 1674: The French West India Company went bankrupt; the Dutch lost New Netherlands to the English.

- 1675: The Dutch New West India Company restarted; Curaçao became a free port.

Dutch & Portuguese: 1671–1701

- 1671-1674: António Garcia, a Portuguese, the heir of Lomelino,[61][62] In 1675 he looked for assistance from Balthasar and his brother Joseph Coymans and the Dutch West India Company, financing the loan and the shipping.[63] Garcia arranged to purchase all the slaves in Curaçao.[64]

- 1676–1679: Manuel Hierro de Castro, and Manuel José Cortizos, members of the Consulado de Sevilla. The Spanish proposed to get the slaves from Cape Verde, located on the demarcation line between the Spanish and Portuguese empire, but this was against the WIC-charter.[65] The Dutch offered to bring the slaves to Hispaniola or the ports on the Spanish Main. From 1662-1690, only twenty slaving vessels set out under the Spanish flag, mostly between 1677 and 1681, an average of less than one a year.[66]

- [Señor. El Maestro Fray Juan de Castro, Religioso de la Orden de Santo Domingo, dize : Que por el año de 1678 hollandose en la Ciudad de Cádiz, le solicitaron D. Baltasar Coymans, y Pedro Bambelle de Nacion Olandeses, para la disposicion de un Asiento, que se auia de hazer para comerciar à Indias, haziendole grandes ofertas... y auian de ser Españoles los que le auian de hazer ; y reconociendo... que se trataua de adulterar el comercio...]

- In May 1679 the Coymans financed slave transports, organized by Captain Juan Barroso del Pozo, of 9,800 "negros" to Curaçao.[67]

- In 1680, Barroso from Seville and Nicolás Porcio, his Venetian son-in-law, became asentistas.[68][69]

- 1682–1688: Juan Barroso del Pozo (–1683) and Nicolás Porcio succeeded in getting the asiento for 6.5 years.[70] It was Porcio who encountered many financial difficulties after the loss of ships and slaves. In 1683 he travelled to Portobelo, but was taken prisoner. He was unable to make his payments to the crown, alleging that the local authorities in Cartagena were working against his interests.[71][72]

- In 1684 Genoa was heavily bombarded by a French fleet as punishment for its alliance with Spain. The Genoese bankers and traders made new economic and financial links with France.

- February 1685 – March 1687: Balthasar Coymans succeeded in ousting Porcio.[73][74] The cash payment of 200,000 Spanish escudos to the Spanish government, an indispensable feature of this bargain, was furnished by the Amsterdam house of Coymans.[75] Coymans made an immediate payment towards some frigates for the Spanish navy being built in Amsterdam and an advance on the dues he would be liable for on goods imported to Spanish America.[71]

- Royal Order, signed "El Rey", commanding Don Balthasar Coymans, Don Juan Barrosa and Don Nicolás Porzio to assemble ten Capuchin monks (Franciscan friars) from either Cadiz or Amsterdam for the purpose of sailing to the coast of Africa to buy slaves, to convert them to Christianity and sell them in the West Indies, 25 March 1685 Balthasar & Johan Coymans.[76]

- Carta de Rodrigo Gómez a [Manuel Diego López de Zúñiga Mendoza Sotomayor, X] Duque de Béjar informando de la concesión de un asiento de negros en el Río de la Plata a favor de Baltasar Coymans y pide recomendaciones personales para que su hijo Pedro sea empleado en ese negocio. Menciona también a Gaspar de Rebolledo, Juan Pimentel como Gobernador de Buenos Aires y a [Carlos José Gutiérrez de los Ríos Roha, VI] Conde de Fernán-Núñez. Antwerp, 1685-04-17.[77]

- July 1686: King Charles II of Spain starts an investigation into the legitimacy of the Asiento.[78] The asiento with B. Coymans is annulled.[79]

- October 1686: The Dutch refuse to accept the "Junta de Asiento de Negros", a commission of dubious authority.

- There is a risk of war between France and Spain; Jamaica is becoming more important than Curaçao.[80]

- 1687–1688: Jan Carçau, or Juan Carcán a former assistant of B. Coymans, takes over the asiento.[81]

- 1688 – October 1691: Nicolás Porcio.

- 1692–1695: Bernardo Francisco Marín de Guzmán

- 1695–1701: Spain returned to the Portuguese; Manuel Ferreira de Carvalho representing the Cacheu and Cape Verde Company.

- Spain was reliant on French ships, even for its bullion fleet.[84]

French: 1701–1713

- 1701–1713: Jean-Baptiste du Casse in name of the Compagnie de Guinée et de l'Assiente des Royaume de la France.[85] In 1701, the French King granted the Guinea Company the Spanish Asiento and the company reorganised. Unlike any other chartered company before it, it included both the Spanish King and the French King as shareholders, for one quarter of the total capital each, which amounted to 100,000 livres. Because of commercial competition paying the French and Spanish for the Asiento was a prominent issue during the Spanish War of Succession.[86] The Portuguese who apparently had trouble letting go of their Asiento rights ... were understood as a French privilege and indeed a marker of superior status of the French abroad.[87] The Asiento did not concern French Caribbean but Spanish America.

- December 2, 1711, Jacques Cassard obtained from the French king the command of a squadron of eight vessels and embarked on an expedition during which he plundered the Portuguese colony Cape Verde. He seized in particular fort Praia on Santiago, Cape Verde, the storehouse of the commerce. Then he set of to Montserrat and Antigua in the Caribbean before heading to the possessions of the Dutch. On 10 October 1712, Cassard attacked Suriname and Berbice, where demanded an amount of 300,000 guilders, which was paid in bills of exchange, slaves and goods. The negotiations with Suriname started, and on 27 October Cassard left with ƒ 747,350 (€ 8.1 million in 2018).[88][89] Cassard returned to Martinique and set sail towards Sint Eustatius. Curaçao was occupied by Cassard from February 18 to 27, 1713, more substantial and richer than the previous ones, but it's also much better defended.

- The King abolished the Asiento Company's monopoly in 1713 and opened the trade south of the Sierra Leone River to French private traders from five specific port towns: Nantes, Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Le Havre and Saint Malo. They paid a tax to the king for each enslaved African transported to the French West Indies upon their return to France.[90]

British: 1713–1750

After the introduction of the Trade with Africa Act 1697 the Royal African Company lost her monopoly and in 1708 it was insolvent.[91]

- 1 May 1713–May 1743: South Sea Company received the Asiento for thirty years,[92][93][94] The English contractor was required to advance 200,000 pesos (₤45,000) to Philip for their share in the trade, to be paid in two equal installments, the first two months after the contract was signed,, the second two months after the first. In addition, the company was allowed to send one ship of 500 tons annually to Portobello to engage in normal trade to avoid contraband.

The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 granted Britain an Asiento lasting 30 years to supply the Spanish colonies with 4,800 slaves per year. Britain was permitted to open offices in Buenos Aires, Caracas, Cartagena, Havana, Panama, Portobello and Vera Cruz to arrange the Atlantic slave trade. An extra legal clause was added; one ship of no more than 500 tons could be sent to one of these places each year (the Navío de Permiso) with general trade goods. (Two ships were in addition to the annual ships, but were not part of the asiento contract.) One quarter of the profits were to be reserved for the King of Spain. There was provision for two extra sailings at the start of the contract. The Asiento was granted in the name of Queen Anne and then contracted to the company.[95]

It was provided that the same reporting procedure might take place at subsequent five year intervals. At the end of the contract the Assentistas were permitted three years to remove their effects from the Indies, adjust their accounts and ‘‘make up a balance of the whole”.[96]

By July the South Sea Company had arranged contracts with the Royal African Company to supply the necessary African slaves to Jamaica. Ten pounds was paid for a slave aged over 16, £8 for one under 16 but over 10. Two-thirds were to be male, and 90% adult. The company trans-shipped 1,230 slaves from Jamaica to America in the first year, plus any that might have been added (against standing instructions) by the ship's captains on their own behalf. On arrival of the first cargoes, the local authorities refused to accept the Asiento, which had still not been officially confirmed there by the Spanish authorities. The slaves were eventually sold at a loss in the West Indies.[97]

In 1714 the government announced that a quarter of profits would be reserved for Queen Anne and a further 7.5% for a financial advisor, Manuel Manasses Gilligan, an English colonist, who operated from the (neutral) Danish West Indies.[98] Some Company board members refused to accept the contract on these terms, and the government was obliged to reverse its decision.[99] Despite these setbacks, the company continued, having raised 200,000 pesos (maybe ducats or Spanish escudos? to finance the operations.[100] Anne had secretly negotiated with France to get its approval regarding the asiento.[101] She boasted to Parliament of her success in taking the asiento away from France and London celebrated her economic coup.[102]

According to Nelson (1945, p. 55) the SSC’s smuggling ‘‘threatened to destroy the entire commercial framework of the Spanish Empire”. Contraband trade became a constant concern of the Spanish who invested heavily in naval protection. While this effectively diminished the profitability of the Asiento, for the Spanish enhanced monitoring activity succeeded in detecting an increasing amount of smuggling (Bernal, 2001).[103]

In 1714 2,680 slaves were carried, and for 1716–17, 13,000 more, but the trade continued to be unprofitable. As the French previously discovered, high costs meant the real profits from the slave trade asiento were in smuggling contraband goods, which evaded import duties and deprived the authorities of much needed revenue. An import duty of 33 pieces of eight was charged on each slave (although for this purpose two children were counted as one adult slave). In 1718 a declaration of war between England and Spain halted operations under the Asiento until 1721. Similar conflicts interrupted the contract from 1727 to 1729 and 1739 to 1748. Increasing knowledge of illicit trading by the SSC resulted in the Spanish tightening on-site monitoring in the Americas during the 1730s.[104] The Spanish then proceeded to seek recompense for clandestine trade carried on by the SSC and others under the veil of the supply of Negroes and the annual ship. Thus a key feature of the depredations crisis was the ongoing failure by the SSC to account and report in a transparent manner.[105] Spain having raised objections to the Asiento clauses, the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) was supplemented by the Treaty of Madrid (5 October 1750). The matter of the asiento was not even mentioned in the treaty, as it had lessened in importance to both nations, although both parties had agreed to resolve outstanding concerns at a "proper time and place".[106] The issue was finally settled in 1750 when Britain agreed to renounce its claim to the asiento in exchange for a payment of £100,000 and British trade with Spanish America under favourable conditions.[107]

It has been estimated that the company transported over 34,000 slaves with deaths comparable to its competitors, which was taken as competence in this area of work at the time.[108] Meanwhile it became a business for privately owned enterprises. In 1740 a Havana company paid Spain for the Asiento to import slaves to Cuba.[109]

- There was no Asiento during the Austrian War of Succession (1740-1748).[110]

- 1748-1750: Spain renewed the Asiento with Britain for four years, but it ended with the Treaty of Madrid (5 October 1750). The Spanish authorities "restore[d] the slave trade to the sphere of internal law from which it should never have left".[111][112] By the middle of the 18th century, British Jamaica and French Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) had become the largest slave societies of the region. As of 1778, the French were importing approximately 13,000 Africans for enslavement to the French West Indies each year.[113]

- After 1762, the British imported more than 10,000 African slaves to Havana. They used it as a base to supply the Caribbean and the lower Thirteen Colonies.[114] In response to the short British occupation of Havana (1762–1763), when the British disembarked 3,500 slaves in ten months, the Spanish crown made determined efforts to revive their own transatlantic slave-trading role.[115]

Spanish: 1765–1779

The asiento was given to a group of Basques from 1765 to 1779.

- 1765–1772: Miguel de Uriarte in name of Aguirre, Aristegui, J.M. Enrile y Compañía, or Compañía Gaditana.

- 1773–1779: Aguirre, Aristegui y Compañía, or Compañía Gaditana.

In 1784, the Spanish crown contracted with the large Liverpool firm to bring slaves to Venezuela and Cuba between 1786-1789.[116]

Spain's connection to the trade with Africa was minor, with only 185 voyages and 61,000 slaves from the continent from 1500 to 1800. This compares to almost 25,000 voyages and over 7 million slaves embarked in total by all nations from 1500 to 1800.

Of the total number slaves, nearly half went to the Caribbean islands and the Guianas, almost 40 percent to Brazil, and some 6 percent to mainland Spanish America. Surprisingly enough, under 5 percent went to North America. These figures may differ as authors of "Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America" suggest half of them went to Brazil and a quarter to the Caribbean.[117]

See also

- Chartered companies

- Spanish Empire

Notes

- Similar patents in the British system were the Virginia Company, the Levant Company and the Merchant Adventurers' patent of trade with the United Provinces (essentially concurrent with the modern day Netherlands). An overview of the British system from a Marxist perspective is given by Robert Brenner, on the editorial board of the New Left Review, in "Merchants and Revolution".

- Reinel introduced 25,000 slaves to Brazil in the following six years. This agreement introduced well-defined characteristics in this type of contract. According to its clauses, Reynel was obliged to introduce 4,250 African slaves annually into the Indies; he could grant "licenses" to anyone who wanted them and he would be in charge of completing the required total if necessary.

References

Citations

- The strategy of Philip II against the Cortes in the 1575 crisis and the domestic credit market freeze Carlos Álvarez-Nogal and Christophe Chamley

- The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659: The Logistics of ...by Geoffrey Parker, p. 125

- A Nation upon the Ocean Sea: Portugal's Atlantic Diaspora and the Crisis of ... by Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, pp. 112–113

- The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: From the Decline of the Roman empire by Sir John Harold Clapham, Eileen Edna Power, p. 372

- [https://brill.com/view/journals/jhil/10/2/article-p229_3.xml The Asiento de Negros and International Law by Andrea Weindl. In: Journal of the History of International Law. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/157180508X359846]

- Carlos Álvarez Nogal (2002) THE ABILITY OF AN ABSOLUTE KING TO BORROW DURING THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURY. SPAIN DURING THE HABSBURG DINASTY [sic, p. 7, 30]

- Haring, Clarence. The Spanish Empire in America, New York: Oxford University Press 1947, p. 219.

- The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659: The Logistics of ...by Geoffrey Parker, p. 127

- Israel, J. (2002). Diasporas within the Diaspora. Jews, Crypto-Jews and the World Maritime Empires (1510–1740).

- The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659: The Logistics of ...by Geoffrey Parker, p. 130

- Haring, The Spanish Empire in America, p. 220.

- Postma, Johannes, The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1815 (Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 29.

- Grete Klingenstein, Heinrich Lutz, Gerald Stourzh, EUROPÄISIERUNG DER ERDE? Studien zur Einwirkung Europas auf die außereuropäische Welt 1980, p. 90.

- Haring, The Spanish Empire in America, p. 219.

- Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, p. 135.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, Volume 5 by Oxford University Press

- Shelly, Cara. "Asiento" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p. 218. New York: Charles Scribner's and Sons 1996, p. 218.

- Mauricio Drelichman and Hans-Joachim Voth, "Lending to the Borrower from Hell: Debt and Default in the Age of Phillip II, 1566-1598", p. 6.

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History by James A. Rawley, Stephen D. Behrendt, p. 63

- Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, p. 181.

- Postma, Johannes, The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1815(Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 21.

- Shelly, "Asiento", p. 218.

- Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery, p. 203.

- Shelly, "Asiento", p. 218

- Haring, The Spanish Empire in America, p. 333.

- Haring, The Spanish Empire in America, p. 220-21

- Thomas, Hugh (1997) The Slave Trade. Simon and Schuster

- Dalla Corte, Gabriela (2006) Homogeneidad, Diferencia y Exclusión en América. Edicions Universitat Barcelona,

- Cortés López, José Luis (2004) Esclavo y Colono. Universidad de Salamanca

- Ngou-Mve 1994, p. 97

- "Portada del Archivo Histórico Nacional". censoarchivos.mcu.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, Volume 5 by Oxford University Press

- A Forgotten Chapter in the History of International Commercial Arbitration: The Slave Trade's Dispute Settlement System by ANNE-CHARLOTTE MARTINEAU DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156518000158 Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 March 2018

- A Forgotten Chapter in the History of International Commercial Arbitration: The Slave Trade's Dispute Settlement System by ANNE-CHARLOTTE MARTINEAU DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156518000158 Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 March 2018

- Bystrom, Kerry (2017) The Global South Atlantic. Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 0823277895.

- Thomas, Hugh (1997). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440 - 1870. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0684835657.

- THE COST OF THE ASIENTO. PRIVATE MERCHANTS, ROYAL MONOPOLIES, AND THE MAKING OF TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE IN THE SPANISH EMPIRE by Alejandro García-Montón, p. 20

- Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 442

- Catia Antunes & Filipa Ribeiro da Silva (2012) Amsterdam merchants in the slave trade and african commerce, 1580s-1670s, p. 7, 18, 23, 29. In: Tijdschrift voor sociale en economische geschiedenis 9 [2012] nr. 4

- Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 443, 446

- LOS BANQUEROS DE FELIPE IV Y LOS METALES PRECIOSOS AMERICANOS (1621 - 1665) Carlos Álvarez Nogal

- Ammann, F. (2019) Looking through the mirrors: materiality and intimacy at Domenico Grillo's mansion in Baroque Madrid. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2015.1131248

- Raphaël Carrasco, Claudette Dérozier, Annie Molinié-Bertrand, Histoire et civilisation de l'Espagne classique : 1492-1808, Nathan, 2001 (ISBN 9782091911526

- Agreement to Deliver two thousand or More Slaves to Curacao (1662)

- "2006.003.0002 a Documents". www.melfisher.org. Archived from the original on 2008-08-08. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- Negro Slavery in Latin America by Rolando Mellafe

- Postma, J.M. (2008) The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1815 blz. 33, Cambridge University Press.

- Ammann, F. (2019) Looking through the mirrors: materiality and intimacy at Domenico Grillo's mansion in Baroque Madrid. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2015.1131248

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History by James A. Rawley, Stephen D. Behrendt, p. 76

- THE COST OF THE ASIENTO. PRIVATE MERCHANTS, ROYAL MONOPOLIES, AND THE MAKING OF TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE IN THE SPANISH EMPIRE by Alejandro García-Montón, p. 17, 18, 23, 26

- Johannes Postma, The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, Cambridge 1990, p. 38-45

- 4 nov. 1669 NA 3678A-f. 172-193 not. F. Tixerandet. Informatie afkomstig van R. Koopman, Zaandam

- The Spanish Seaborne Empire By J. H. Parry, p. 269

- The slave trade: the story of the Atlantic slave trade, 1440–1870 Door Hugh Thomas, p. 213.

- The Genoese in Spain: Gabriel Bocángel y Unzueta (1603–1658): a biography by Trevor J. Dadson

- Elis, D. and Richardson, D. (eds.), Extending the Frontiers: Essays on the New Transatlantic Slave Trade Database (2008), p. 35.

- Royal African Company Trades for Commodities Along the West African Coast

- Ammann, F. (2019) Looking through the mirrors: materiality and intimacy at Domenico Grillo's mansion in Baroque Madrid. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2015.1131248

- Barry, Boubacar (1998). Senegambia and the Atlantic slave trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62, 66. ISBN 0-521-59226-7.

- Klooster, W. (1997): Slavenvaart op Spaanse kusten. De Nederlandse slavenhandel met Spaans Amerika, 1648-1701 in Tijdschrift voor de Zeegeschiedenis p. 127.

- Coleccion de los tratados de paz, alianza, neutralidad,: garantia ..., Part 2, p. 136

- Pertinent en waarachtig verhaal van alle de handelingen en directie van Pedro van Belle omtrent den slavenhandel, ofwel het Assiento de Negros ...

- Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World by Linda M. Rupert, p. 78

- The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1815 by Johannes Postma p. 40

- Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. In: AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 450

- Pertinent en waarachtig verhaal van alle de handelingen en directie van Pedro van Belle omtrent den slavenhandel, ofwel het Assiento de Negros ...

- Shaw, C.M. (199) The overseas Spanish Empire and the Dutch Republic before and after the Peace of Munster", In: De zeventiende Eeuw, 13 (1997), pp. 131-139.

- The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870 by Hugh Thomas

- Coleccion de los tratados de paz, alianza, neutralidad,: garantia ..., Part 2, p. 478, 681

- Wills, J.E. (2001) 1688. A global history, p. 50.

- Slavery and Antislavery in Spain's Atlantic Empire, p. 25. Edited by Josep M. Fradera, Christopher Schmidt-Nowara†

- Barbour, V. (1963) Capitalism in Amsterdam in the 17th century, p. 110-111

- Davies, Kenneth Gordon (1957). The Royal African Company. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415190770.

- Barbour, V. (1963) Capitalism in Amsterdam in the 17th century, p. 110-111

- "Spanish Slavery.- [Charle S II, King of Spain, 1665–1700 Royal Order, signed 'El Rey', commanding Don Balthasar Coymans, Don Juan Barrosa & Don Nicolas Porzio to assemble 10 Capuchin monks (Franciscan friars) from either Cadiz or Amsterdam for the". invaluable.com. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- "MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE - Portal de Archivos Españoles". pares.mcu.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- The transatlantic slave trade: a history door James A. Rawley, Stephen D. Behrendt

- Wright, I.A. (1924) The Coymans asiento (1685–1689)

- Négoce, ports et océans, XVIe-XXe siècles: mélanges offerts à Paul Butel by Silvia Marzagalli, Paul Butel, Hubert Bonin

- The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1815 by Johannes Postma, p. 41

- Wright, I.A. (1924) The Coymans asiento (1685–1689), p. 51

- Wills, J.E. (2001) 1688. A global history, p. 51.

- The South Sea Company’s slaving activities by Helen Paul, University of St. Andrews

- "Africa Focus: Africans in bondage : studies in slavery and the slave trade : essays in honor of Philip D. Curtin on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of African Studies at the University of Wisconsin: Chapter 2: The company trade and the numerical distribution of slaves to Spanish America, 1703–1739". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- Colonial Legacies: The Problem of Persistence in Latin American History edited by Jeremy Adelman

- The Sun King's Atlantic: Drugs, Demons and Dyestuffs in the Atlantic World ...by Jutta Wimmler, p. 149

- "De waarde van de gulden / euro". Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Digital Library for Dutch Literature, Jan Jacob Hartsinck (1770). "Beschryving van Guiana, of de wilde kust in Zuid-America" (in Dutch).

- Heijmans, E. A. R. (2018). The Agency of Empire: personal connections and individual strategies in the shaping of the French Early Modern Expansion (1686–1746), pp. 47, 49

- The African slave trade and its suppression: a classified and annotated… By Peter C. Hogg

- Silver, Trade, and War: Spain and America in the Making of Early Modern Europe by Stanley J. Stein, Barbara H. Stein, p. 137

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 761.

- Accounting and international relations: Britain, Spain and the Asiento treaty Salvador Carmona, Rafael Donoso, Stephen P. Walker, p. 257-258

- Carswell p. 64-66

- (A Collection of all the Treaties, 1785; AGI. Indiferente General. Legajo 2785) Accounting and international relations: Britain, Spain and the Asiento treaty Salvador Carmona, Rafael Donoso, Stephen P. Walker, p. 259

- Carswell p. 65-66

- Empire at the Periphery: British Colonists, Anglo-Dutch Trade, and the ... by Christian J. Koot, p. 196

- Carswell p. 67

- BRITISH TRADE WITH SPANISH AMERICA UNDER THE ASIENTO 1713 - 1740 by Victoria Gardner Sorsby, p. 16?

- Edward Gregg. Queen Anne (2001), pp. 341, 361.

- Hugh Thomas (1997). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440 – 1870. Simon and Schuster. p. 236.

- Accounting and international relations: Britain, Spain and the Asiento treaty Salvador Carmona, Rafael Donoso, Stephen P. Walker, p. 257-258

- Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623-1775 By Richard B. Sheridan, p. 427

- Accounting and international relations: Britain, Spain and the Asiento treaty Salvador Carmona, Rafael Donoso, Stephen P. Walker, p. 258-259, 261, 263, 265

- Anderson, Adam; Combe, William (1801). An Historical and Chronological Deduction of the Origin of Commerce, from the Earliest Accounts. J Archer., p. 277.

- Simms, Brendan (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire. Penguin Books., p. 381.

- Paul, Helen. "The South Sea Company's slaving activities" (PDF). ISSN 0966-4246.

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History by James A. Rawley, Stephen D. Behrendt, p. 62

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History by James A. Rawley, Stephen D. Behrendt, p. 62

- Scelle, G., Une institution internationale disparue: l'assiento des nègres, (1906) 13 RGDIP 357, p. 395.

- A Forgotten Chapter in the History of International Commercial Arbitration: The Slave Trade's Dispute Settlement System by ANNE-CHARLOTTE MARTINEAU DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156518000158 Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 March 2018

- Kitchin, Thomas (1778). The Present State of the West-Indies: Containing an Accurate Description of What Parts Are Possessed by the Several Powers in Europe. London: R. Baldwin. p. 21.

- Rogozinsky, Jan. A Brief History of the Caribbean. Plume. 1999.

- Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. In: AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 450

- Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT, p. 450

- Atlantic History and the Slave Trade to Spanish America ALEX BORUCKI, DAVID ELTIS, AND DAVID WHEAT. In: AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 2015, p. 440

Bibliography

- Barreto, Maxcarenhas (1992). The Portuguese Columbus: Secret Agent of King John II. Springer. ISBN 1349219940.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blackburn, Robin (1998). The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492–1800. Verso. ISBN 1859841953.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Braun, Harald E (2013). Theorising the Ibero-American Atlantic. BRILL. ISBN 900425806X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bystrom, Kerry (2017). The Global South Atlantic. Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 0823277895.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cardoso, Gerald (1983). Negro Slavery in the Sugar Plantations of Veracruz and Pernambuco, 1550–1680: A Comparative Study. University Press of America. ISBN 0819129267.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Alencastro, Luiz Felipe (2018). The Trade in the Living: The Formation of Brazil in the South Atlantic, Sixteenth to Seventeenth Centuries. SUNY Press. ISBN 1438469292.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ingram, Kevin (2015). The Conversos and Moriscos in Late Medieval Spain and Beyond, Volume 3: Displaced Persons. BRILL. ISBN 9004306366.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klooster, Wim (2009). Migration, Trade, and Slavery in an Expanding World: Essays in Honor of Pieter Emmer. BRILL. ISBN 9004176209.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newson, Linda A (2007). From Capture to Sale: The Portuguese Slave Trade to Spanish South America in the Early Seventeenth Century. BRILL. ISBN 9004156798.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ngou-Mve, Nicolás (1994). El Africa bantú en la colonización de México (1595-1640). Editorial CSIC - CSIC Press. ISBN 8400074203.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ribeiro da Silva, Filipa (2011). Dutch and Portuguese in Western Africa: Empires, Merchants and the Atlantic System, 1580–1674. BRILL. ISBN 9004201513.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richardson, David (2014). Networks and Trans-Cultural Exchange: Slave Trading in the South Atlantic, 1590–1867. BRILL. ISBN 9004280588.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saraiva, António José (2001). The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536–1765. BRILL. ISBN 9004120807.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goslinga, C. Ch. (1985). The Dutch in the Caribbean and in the Guianas 1680–1791. Assen: Van Gorcum. ISBN 90-232-2060-9.

- David Marley (ed.), Reales asientos y licencias para la introduccion de esclavos negros a la America Espagnola (1676-1789), ISBN 0-88653-009-1 (Windsor, Canada. 1985).

- Postma, J. M. (2008). The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600–1815. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36585-7.