Frigate

A frigate (/ˈfrɪɡət/) is a type of warship, having various sizes and roles over time.

In the 17th century, a frigate was any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built". These could be warships carrying their principal batteries of carriage-mounted guns on a single deck or on two decks (with further smaller carriage-mounted guns usually carried on the forecastle and quarterdeck of the vessel). The term was generally used for ships too small to stand in the line of battle, although early line-of-battle ships were frequently referred to as frigates when they were built for speed.

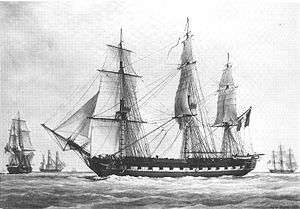

In the 18th century, frigates were full-rigged ships, that is square-rigged on all three masts, they were built for speed and handiness, had a lighter armament than a ship of the line, and were used for patrolling and escort. In the definition adopted by the British Admiralty, they were rated ships of at least 28 guns, carrying their principal armaments upon a single continuous deck – the upper deck – while ships of the line possessed two or more continuous decks bearing batteries of guns.

In the late 19th century (beginning about 1858 with the construction of prototypes by the British and French navies), the armoured frigate was a type of ironclad warship that for a time was the most powerful type of vessel afloat. The term "frigate" was used because such ships still mounted their principal armaments on a single continuous upper deck.

In modern navies, frigates are used to protect other warships and merchant-marine ships, especially as anti-submarine warfare (ASW) combatants for amphibious expeditionary forces, underway replenishment groups, and merchant convoys. Ship classes dubbed "frigates" have also more closely resembled corvettes, destroyers, cruisers and even battleships. Some European navies such as the Dutch, French, German or Spanish ones use the term "frigate" for both their destroyers and frigates. The rank "frigate captain" derives from the name of this type of ship.

Age of sail

Origins

The term "frigate" (Italian: fregata; Spanish/Catalan/Portuguese/Sicilian: fragata; Dutch: fregat; French: frégate) originated in the Mediterranean in the late 15th century, referring to a lighter galley-type warship with oars, sails and a light armament, built for speed and maneuverability.[1] The etymology of the word remains uncertain, although it may have originated as a corruption of aphractus, a Latin word for an open vessel with no lower deck. Aphractus, in turn, derived from the Ancient Greek phrase ἄφρακτος ναῦς (aphraktos naus) – "undefended ship".

In 1583, during the Eighty Years' War of 1568–1648, Habsburg Spain recovered the southern Netherlands from the Protestant rebels. This soon resulted in the use of the occupied ports as bases for privateers, the "Dunkirkers", to attack the shipping of the Dutch and their allies. To achieve this the Dunkirkers developed small, maneuverable, sailing vessels that came to be referred to as frigates. The success of these Dunkirker vessels influenced the ship design of other navies contending with them, but because most regular navies required ships of greater endurance than the Dunkirker frigates could provide, the term soon came to apply less exclusively to any relatively fast and elegant sail-only warship. In French, the term "frigate" gave rise to a verb – frégater, meaning 'to build long and low', and to an adjective, adding more confusion. Even the huge English Sovereign of the Seas could be described as "a delicate frigate" by a contemporary after her upper decks were reduced in 1651.[2]

The navy of the Dutch Republic became the first navy to build the larger ocean-going frigates. The Dutch navy had three principal tasks in the struggle against Spain: to protect Dutch merchant ships at sea, to blockade the ports of Spanish-held Flanders to damage trade and halt enemy privateering, and to fight the Spanish fleet and prevent troop landings. The first two tasks required speed, shallowness of draft for the shallow waters around the Netherlands, and the ability to carry sufficient supplies to maintain a blockade. The third task required heavy armament, sufficient to stand up to the Spanish fleet. The first of the larger battle-capable frigates were built around 1600 at Hoorn in Holland.[3] By the later stages of the Eighty Years' War the Dutch had switched entirely from the heavier ships still used by the English and Spanish to the lighter frigates, carrying around 40 guns and weighing around 300 tons.

The effectiveness of the Dutch frigates became most evident in the Battle of the Downs in 1639, encouraging most other navies, especially the English, to adopt similar designs.

The fleets built by the Commonwealth of England in the 1650s generally consisted of ships described as "frigates", the largest of which were two-decker "great frigates" of the third rate. Carrying 60 guns, these vessels were as big and capable as "great ships" of the time; however, most other frigates at the time were used as "cruisers": independent fast ships. The term "frigate" implied a long hull-design, which relates directly to speed (see hull speed) and which also, in turn, helped the development of the broadside tactic in naval warfare.

At this time, a further design evolved, reintroducing oars and resulting in galley frigates such as HMS Charles Galley of 1676, which was rated as a 32-gun fifth-rate but also had a bank of 40 oars set below the upper deck which could propel the ship in the absence of a favourable wind.

In Danish, the word "fregat" often applies to warships carrying as few as 16 guns, such as HMS Falcon, which the British classified as a sloop.

Under the rating system of the Royal Navy, by the middle of the 18th century, the term "frigate" was technically restricted to single-decked ships of the fifth rate, though small 28-gun frigates classed as sixth rate.[1]

Classic design

The classic sailing frigate, well-known today for its role in the Napoleonic wars, can be traced back to French developments in the second quarter of the 18th century. The French-built Médée of 1740 is often regarded as the first example of this type. These ships were square-rigged and carried all their main guns on a single continuous upper deck. The lower deck, known as the "gun deck", now carried no armament, and functioned as a "berth deck" where the crew lived, and was in fact placed below the waterline of the new frigates. The typical earlier cruiser had a partially armed lower deck, from which it was known as a 'half-battery' or demi-batterie ship. Removing the guns from this deck allowed the height of the hull upperworks to be lowered, giving the resulting 'true-frigate' much improved sailing qualities. The unarmed deck meant that the frigate's guns were carried comparatively high above the waterline; as a result, when seas were too rough for two-deckers to open their lower deck gun-ports, frigates were still able to fight with all their guns (see the Action of 13 January 1797, for an example when this was decisive).[4][5]

A total of fifty-nine French sailing frigates were built between 1777 and 1790, with a standard design averaging a hull length of 135 ft (41 m) and an average draught of 13 ft (4.0 m). The new frigates recorded sailing speeds of up to 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph), significantly faster than their predecessor vessels.[4]

The Royal Navy captured a number of the new French frigates, including Médée, during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) and were impressed by them, particularly for their inshore handling capabilities. They soon built copies (ordered in 1747), based on a French privateer named Tygre, and started to adapt the type to their own needs, setting the standard for other frigates as the leading naval power. The first British frigates carried 28 guns including an upper deck battery of twenty-four 9-pounder guns (the remaining four smaller guns were carried on the quarter deck) but soon developed into fifth-rate ships of 32 or 36 guns including an upper deck battery of twenty-six 12-pounder guns, with the remaining six or ten smaller guns carried on the quarter deck and forecastle.[6]

Heavy frigate

In 1778, the British Admiralty introduced a larger "heavy" frigate, with a main battery of twenty-six or twenty-eight 18-pounder guns (with smaller guns carried on the quarter deck and forecastle). This move may reflect the naval conditions at the time, with both France and Spain as enemies the usual British preponderance in ship numbers was no longer the case and there was pressure on the British to produce cruisers of individually greater force. In reply, the first French 18-pounder frigates were laid down in 1781. The 18-pounder frigate eventually became the standard frigate of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. The British produced larger, 38-gun, and slightly smaller, 36-gun, versions and also a 32-gun design that can be considered an 'economy version'. The 32-gun frigates also had the advantage that they could be built by the many smaller, less-specialised shipbuilders.[7][8]

Frigates could (and usually did) additionally carry smaller carriage-mounted guns on their quarter decks and forecastles (the superstructures above the upper deck). Technically, rated ships with fewer than 28 guns could not be classed as frigates but as "post ships"; however, in common parlance most post ships were often described as "frigates", the same casual misuse of the term being extended to smaller two-decked ships that were too small to stand in the line of battle. In 1778 the Carron Iron Company of Scotland produced a naval gun which would revolutionise the armament of smaller naval vessels, including the frigate. The carronade was a large calibre, short-barrelled naval cannon which was light, quick to reload and needed a smaller crew than a conventional long gun. Due to its lightness it could be mounted on the forecastle and quarter deck of frigates. It greatly increased the firepower, measured in weight of metal (the combined weight of all projectiles fired in one broadside), of these vessels. The disadvantages of the carronade were that it had a much shorter range and was less accurate than a long gun. The British quickly saw the advantages of the new weapon and soon employed it on a wide scale. The US Navy also copied the design soon after its appearance. The French and other nations eventually adopted variations of the weapon in succeeding decades. The typical heavy frigate had a main armament of 18-pounder long guns, plus 32-pounder carronades mounted on its upper decks.[9]

Super-heavy frigates

The first 'super-heavy frigates', armed with 24-pounder long guns, were built by the naval architect F H Chapman for the Swedish navy in 1782. Because of a shortage of ships-of-the-line, the Swedes wanted these frigates, the Bellona class, to be able to stand in the battle line in an emergency. In the 1790s the French built a small number of large 24-pounder frigates, such as Forte and Egyptienne, they also cut-down (reduced the height of the hull to give only one continuous gun deck) a number of older ships-of-the-line (including Diadème) to produce super-heavy frigates, the resulting ship was known as a rasée. It is not known whether the French were seeking to produce very potent cruisers or merely to address stability problems in old ships. The British, alarmed by the prospect of these powerful heavy frigates, responded by rasée-ing three of the smaller 64-gun battleships, including Indefatigable, which went on to have a very successful career as a frigate. At this time the British also built a few 24-pounder-armed large frigates, the most successful of which was HMS Endymion (1,277 tons).[10][11]

In 1797, three of the United States Navy's first six major ships were rated as 44-gun frigates, which operationally carried fifty-six to sixty 24-pounder long guns and 32-pounder or 42-pounder carronades on two decks; they were exceptionally powerful. These ships were so large, at around 1,500 tons, and well-armed that they were often regarded as equal to ships of the line, and after a series of losses at the outbreak of the War of 1812, Royal Navy fighting instructions ordered British frigates (usually of 38 guns or less) to never engage the large American frigates at any less than a 2:1 advantage. USS Constitution, preserved as a museum ship by the US Navy, is the oldest commissioned warship afloat, and is a surviving example of a frigate from the Age of Sail. Constitution and her sister ships President and United States were created in a response to deal with the Barbary Coast pirates and in conjunction with the Naval Act of 1794. Joshua Humphreys proposed that only live oak, a tree that grew only in America, should be used to build these ships. The three big frigates, when built, had a distinctive building pattern which minimised "hogging" (in which the centre of the keel rises while both ends drop) and improved hydrodynamic efficiency. Diagonal riders were employed, eight on each side, that sat at a 45-degree angle to the horizontal. These beams were about 2 feet (61 cm) wide and around 1 foot (30 cm) thick and helped to maintain the shape of the hull, serving also to reduce flexibility and to minimize impacts.[12]

The British, wounded by repeated defeats in single-ship actions, responded to the success of the American 44s in three ways. They built a class of conventional 40-gun, 24-pounder armed frigates on the lines of Endymion. They cut down three old 74-gun battleships into rasées, producing frigates with a 32-pounder main armament, supplemented by 42-pounder carronades. These had an armament that far exceeded the power of the American ships. Finally, Leander and Newcastle, 1,500-ton spar-decked frigates (with an enclosed waist, giving a continuous line of guns from bow to stern at the level of the quarter deck/forecastle), were built, which were an almost exact match in size and firepower to the American 44-gun frigates.[13]

Role

Frigates were perhaps the hardest-worked of warship types during the Age of Sail. While smaller than a ship-of-the-line, they were formidable opponents for the large numbers of sloops and gunboats, not to mention privateers or merchantmen. Able to carry six months' stores, they had very long range; and vessels larger than frigates were considered too valuable to operate independently.

Frigates scouted for the fleet, went on commerce-raiding missions and patrols, and conveyed messages and dignitaries. Usually, frigates would fight in small numbers or singly against other frigates. They would avoid contact with ships-of-the-line; even in the midst of a fleet engagement it was bad etiquette for a ship of the line to fire on an enemy frigate which had not fired first.[14] Frigates were involved in fleet battles, often as "repeating frigates". In the smoke and confusion of battle, signals made by the fleet commander, whose flagship might be in the thick of the fighting, might be missed by the other ships of the fleet.[15] Frigates were therefore stationed to windward or leeward of the main line of battle, and had to maintain a clear line of sight to the commander's flagship. Signals from the flagship were then repeated by the frigates, which themselves standing out of the line and clear from the smoke and disorder of battle, could be more easily seen by the other ships of the fleet.[15] If damage or loss of masts prevented the flagship from making clear conventional signals, the repeating frigates could interpret them and hoist their own in the correct manner, passing on the commander's instructions clearly.[15]

For officers in the Royal Navy, a frigate was a desirable posting. Frigates often saw action, which meant a greater chance of glory, promotion, and prize money.

Unlike larger ships that were placed in ordinary, frigates were kept in service in peacetime as a cost-saving measure and to provide experience to frigate captains and officers which would be useful in wartime. Frigates could also carry marines for boarding enemy ships or for operations on shore; in 1832, the frigate USS Potomac landed a party of 282 sailors and Marines ashore in the US Navy's first Sumatran expedition.

Frigates remained a crucial element of navies until the mid-19th century. The first ironclads were classified as "frigates" because of the number of guns they carried. However, terminology changed as iron and steam became the norm, and the role of the frigate was assumed first by the protected cruiser and then by the light cruiser.

Frigates are often the vessel of choice in historical naval novels due to their relative freedom compared to ships-of-the-line (kept for fleet actions) and smaller vessels (generally assigned to a home port and less widely ranging). For example, the Patrick O'Brian Aubrey–Maturin series, C. S. Forester's Horatio Hornblower series and Alexander Kent's Richard Bolitho series. The motion picture Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World features a reconstructed historic frigate, HMS Rose, to depict Aubrey's frigate HMS Surprise.

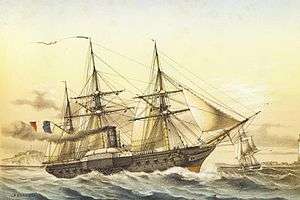

Age of steam

Vessels classed as frigates continued to play a great role in navies with the adoption of steam power in the 19th century. In the 1830s, navies experimented with large paddle steamers equipped with large guns mounted on one deck, which were termed "paddle frigates".

From the mid-1840s on, frigates which more closely resembled the traditional sailing frigate were built with steam engines and screw propellers. These "screw frigates", built first of wood and later of iron, continued to perform the traditional role of the frigate until late in the 19th century.

Armoured frigate

From 1859, armour was added to ships based on existing frigate and ship of the line designs. The additional weight of the armour on these first ironclad warships meant that they could have only one gun deck, and they were technically frigates, even though they were more powerful than existing ships-of-the-line and occupied the same strategic role. The phrase "armoured frigate" remained in use for some time to denote a sail-equipped, broadside-firing type of ironclad.

After 1875, the term "frigate" fell out of use. Vessels with armoured sides were designated as "battleships" or "armoured cruisers", while "protected cruisers" only possessed an armoured deck, and unarmoured vessels, including frigates and sloops, were classified as "unprotected cruisers".

World War II

.jpg)

Modern frigates are related to earlier frigates only by name. The term "frigate" was readopted during the Second World War by the British Royal Navy to describe an anti-submarine escort vessel that was larger than a corvette, while smaller than a destroyer. Equal in size and capability to the American destroyer escort, frigates are usually less expensive to build and maintain.[16] Anti-submarine escorts had previously been classified as sloops by the Royal Navy, and the Black Swan-class sloops of 1939–1945 were as large as the new types of frigate, and more heavily armed. Twenty-two of these were reclassified as frigates after the war, as were the remaining 24 smaller Castle-class corvettes.

The frigate was introduced to remedy some of the shortcomings inherent in the Flower-class corvette design: limited armament, a hull form not suited to open-ocean work, a single shaft which limited speed and manoeuvrability, and a lack of range. The frigate was designed and built to the same mercantile construction standards (scantlings) as the corvette, allowing manufacture by yards unused to warship construction. The first frigates of the River class (1941) were essentially two sets of corvette machinery in one larger hull, armed with the latest Hedgehog anti-submarine weapon.

The frigate possessed less offensive firepower and speed than a destroyer, but such qualities were not required for anti-submarine warfare. Submarines were slow while submerged, and ASDIC sets did not operate effectively at speeds of over 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h). Rather, the frigate was an austere and weatherly vessel suitable for mass-construction and fitted with the latest innovations in anti-submarine warfare. As the frigate was intended purely for convoy duties, and not to deploy with the fleet, it had limited range and speed.

The contemporary German Flottenbegleiter ("fleet escorts"), also known as "F-Boats", were essentially frigates.[17] They were based on a pre-war Oberkommando der Marine concept of vessels which could fill roles such as fast minesweeper, minelayer, merchant escort and anti-submarine vessel. Because of the Treaty of Versailles their displacement was officially limited to 600 tons, although in reality they exceeded this by about 100 tons. F-boats had two stacks and two 105 mm gun turrets. The design was flawed because of its narrow beam, sharp bow and unreliable high pressure steam turbines. F-boats were succeeded in operational duties by Type 35 and Elbing-class torpedo boats. Flottenbegleiter remained in service as advanced training vessels.

It was not until the Royal Navy's Bay class of 1944 that a British design classified as a "frigate" was produced for fleet use, although it still suffered from limited speed. These anti-aircraft frigates, built on incomplete Loch-class frigate hulls, were similar to the United States Navy's destroyer escorts (DE), although the latter had greater speed and offensive armament to better suit them to fleet deployments. The destroyer escort concept came from design studies by the General Board of the United States Navy in 1940, as modified by requirements established by a British commission in 1941[18] prior to the American entry into the war, for deep-water escorts. The American-built destroyer escorts serving in the British Royal Navy were rated as Captain-class frigates. The U.S. Navy's two Canadian-built Asheville-class and 96 British-influenced, American-built Tacoma-class frigates that followed originally were classified as "patrol gunboats" (PG) in the U.S. Navy but on 15 April 1943 were all reclassified as patrol frigates (PF).

Contemporary

Guided-missile role

_Frigate.jpg)

_at_sea_off_San_Diego%2C_in_May_1978.jpg)

The introduction of the surface-to-air missile after World War II made relatively small ships effective for anti-aircraft warfare: the "guided missile frigate". In the USN, these vessels were called "ocean escorts" and designated "DE" or "DEG" until 1975 – a holdover from the World War II destroyer escort or "DE". The Royal Canadian Navy and British Royal Navy maintained the use of the term "frigate"; likewise, the French Navy refers to missile-equipped ship, up to cruiser-sized ships (Suffren, Tourville, and Horizon classes), by the name of "frégate", while smaller units are named aviso. The Soviet Navy used the term "guard-ship" (сторожевой корабль).

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the United States Navy commissioned ships classed as guided missile frigates (hull classification symbol DLG or DLGN, literally meaning guided missile destroyer leaders), which were actually anti-aircraft warfare cruisers built on destroyer-style hulls. These had one or two twin launchers per ship for the RIM-2 Terrier missile, upgraded to the RIM-67 Standard ER missile in the 1980s. This type of ship was intended primarily to defend aircraft carriers against anti-ship cruise missiles, augmenting and eventually replacing converted World War II cruisers (CAG/CLG/CG) in this role. The guided missile frigates also had an anti-submarine capability that most of the World War II cruiser conversions lacked. Some of these ships – Bainbridge and Truxtun along with the California and Virginia classes – were nuclear-powered (DLGN).[19] These "frigates" were roughly mid-way in size between cruisers and destroyers. This was similar to the use of the term "frigate" during the age of sail during which it referred to a medium-sized warship, but it was inconsistent with conventions used by other contemporary navies which regarded frigates as being smaller than destroyers. During the 1975 ship reclassification, the large American frigates were redesignated as guided missile cruisers or destroyers (CG/CGN/DDG), while ocean escorts (the American classification for ships smaller than destroyers, with hull symbol DE/DEG (destroyer escort)) were reclassified as frigates (FF/FFG), sometimes incorrectly called "fast frigates". In the late 1970s the US Navy introduced the 51-ship Oliver Hazard Perry-class guided missile frigates (FFG), the last of which was decommissioned in 2015, although some serve in other navies.[20] By 1995 the older guided missile cruisers and destroyers were replaced by the Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Arleigh Burke-class destroyers.[21]

One of the most successful post-1945 designs was the British Leander-class frigate, which was used by several navies. Laid down in 1959, the Leander-class was based on the previous Type 12 anti-submarine frigate but equipped for anti-aircraft use as well. They were used by the UK into the 1990s, at which point some were sold onto other navies. The Leander design, or improved versions of it, were licence-built for other navies as well.

Nearly all modern frigates are equipped with some form of offensive or defensive missiles, and as such are rated as guided-missile frigates (FFG). Improvements in surface-to-air missiles (e.g., the Eurosam Aster 15) allow modern guided-missile frigates to form the core of many modern navies and to be used as a fleet defence platform, without the need for specialised anti-air warfare frigates.

Other uses

The Royal Navy Type 61 Salisbury class were "air direction" frigates equipped to track aircraft. To this end they had reduced armament compared to the Type 41 Leopard-class air-defence frigates built on the same hull.

Multi-role frigates like the MEKO 200, Anzac and Halifax classes are designed for navies needing warships deployed in a variety of situations that a general frigate class would not be able to fulfill and not requiring the need for deploying destroyers.

Anti-submarine role

.jpg)

At the opposite end of the spectrum, some frigates are specialised for anti-submarine warfare. Increasing submarine speeds towards the end of World War II (see German Type XXI submarine) greatly reduced the margin of speed superiority of frigate over submarine. The frigate could no longer be slow and powered by mercantile machinery and consequently postwar frigates, such as the Whitby class, were faster.

Such ships carry improved sonar equipment, such as the variable depth sonar or towed array, and specialised weapons such as torpedoes, forward-throwing weapons such as Limbo and missile-carried anti-submarine torpedoes such as ASROC or Ikara. Surface-to-air missiles such as Sea Sparrow and surface-to-surface missiles such as Exocet give them defensive and offensive capabilities. The Royal Navy's original Type 22 frigate is an example of a specialised anti-submarine warfare frigate.

Especially for anti-submarine warfare, most modern frigates have a landing deck and hangar aft to operate helicopters, eliminating the need for the frigate to close with unknown sub-surface threats, and using fast helicopters to attack nuclear submarines which may be faster than surface warships. For this task the helicopter is equipped with sensors such as sonobuoys, wire-mounted dipping sonar and magnetic anomaly detectors to identify possible threats, and torpedoes or depth-charges to attack them.

With their onboard radar helicopters can also be used to reconnoitre over-the-horizon targets and, if equipped with anti-ship missiles such as Penguin or Sea Skua, to attack them. The helicopter is also invaluable for search and rescue operation and has largely replaced the use of small boats or the jackstay rig for such duties as transferring personnel, mail and cargo between ships or to shore. With helicopters these tasks can be accomplished faster and less dangerously, and without the need for the frigate to slow down or change course.

Air defense role

Some frigates are specialised in airdefense, because of the major developments in fighter jets and ballistic missiles. An example is the De Zeven Provinciën-class air defense and command frigate of the Royal Dutch Navy. These ships are armed with VL Standard Missile 2 Block IIIA, one or two Goalkeeper CIWS systems, (HNLMS Evertsen has two Goalkeepers, the rest of the ships have the capacity for another one.) VL Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles, a special SMART-L Radar and a Thales APAR, all of which are for air defense. Another example is the Iver Huitfeldt class of the Danish Navy.[23]

Further developments

Stealth technology has been introduced in modern frigate design by the French La Fayette class design.[24] Frigate shapes are designed to offer a minimal radar cross section, which also lends them good air penetration; the maneuverability of these frigates has been compared to that of sailing ships. Examples are the Italian and French Horizon class with the Aster 15 and Aster 30 missile for anti-missile capabilities, the German F125 and Sachsen-class frigates, the Turkish TF2000 type frigates with the MK-41 VLS, the Indian Shivalik, Talwar class and Nilgiri classes with the Brahmos missile system and the Malaysian Maharaja Lela-class frigate with the Naval Strike Missile.

The modern French Navy applies the term first-class frigate and second-class frigate to both destroyers and frigates in service. Pennant numbers remain divided between F-series numbers for those ships internationally recognised as frigates and D-series pennant numbers for those more traditionally recognised as destroyers. This can result in some confusion as certain classes are referred to as frigates in French service while similar ships in other navies are referred to as destroyers. This also results in some recent classes of French ships such as the Horizon class being among the largest in the world to carry the rating of frigate.

.jpg)

In the German Navy, frigates were used to replace aging destroyers; however in size and role the new German frigates exceed the former class of destroyers. The future German F125-class frigates will be the largest class of frigates worldwide with a displacement of more than 7,200 tons. The same was done in the Spanish Navy, which went ahead with the deployment of the first Aegis frigates, the Álvaro de Bazán-class frigates.

Littoral combat ship (LCS)

_at_Naval_Air_Station_Key_West_on_29_March_2010_(100329-N-1481K-298).jpg)

Some new classes of ships similar to corvettes are optimized for high-speed deployment and combat with small craft rather than combat between equal opponents; an example is the U.S. littoral combat ship (LCS). As of 2015, all Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates in the United States Navy have been decommissioned, and their role partially being assumed by the new LCS. While the LCS class ships are smaller than the frigate class they will replace, they offer a similar degree of weaponry while requiring less than half the crew complement and offering a top speed of over 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph). A major advantage for the LCS ships is that they are designed around specific mission modules allowing them to fulfill a variety of roles. The modular system also allows for most upgrades to be performed ashore and installed later into the ship, keeping the ships available for deployment for the maximum time.

The latest U.S. deactivation plans means that this is the first time that the U.S. Navy has been without a frigate class of ships since 1943 (technically USS Constitution is rated as a frigate and is still in commission, but does not count towards Navy force levels).[25]

The remaining 20 LCSs to be acquired from 2019 and onwards that will be enhanced will be designated as frigates, and existing ships given modifications may also have their classification changed to FF as well.[26]

Frigates in preservation

A few nations have frigates on display as museum ships. They are:

Original sailing frigates

- USS Constitution in Boston, United States. Second oldest commissioned warship in the world, oldest commissioned warship afloat. Active as the flagship of the United States Navy.

- NRP Dom Fernando II e Glória in Almada, Portugal.

- HMS Trincomalee in Hartlepool, England.

- HMS Unicorn in Dundee, Scotland.

Replica sailing frigates

- Hermione, sailing replica of the 1779 Hermione which carried Lafayette to the United States.

- Étoile du Roy, originally named Grand Turk was built for the TV series Hornblower in 1997. She was sold to France in 2010 and renamed Étoile du Roy.

- Russian frigate Shtandart, a sailing replica of Russia's first warship, homeported in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

- HMS Surprise in San Diego, United States, replica of HMS Rose, used in the film, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.

Steam frigates

- HNLMS Bonaire in Den Helder, Netherlands.

- Danish frigate Jylland in Ebeltoft, Denmark.

- Japanese frigate Kaiyō Maru, replica in Esashi, Japan.

- HMS Warrior in Portsmouth, England.

- ARA Presidente Sarmiento in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Modern frigates

- HDMS Peder Skram in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- HMAS Diamantina in Brisbane, Australia.

- TCG Ege (F256), formerly USS Ainsworth in Izmit, Turkey.

- ROKS Taedong (PF-63), formerly USS Tacoma in South Korea.

- ROKS Ulsan (FF-951), in Ulsan, South Korea.

- ROKS Seoul (FF-952), in Seoul, South Korea.

- HTMS Tachin (PF-1), formerly USS Glendale in Nakhon Nayok, Thailand.

- HTMS Prasase (PF-2), formerly USS Gallup in Rayong Province, Thailand.

- CNS Nanchong (FF-502) in Qingdao, China.

- CNS Yingtan (FFG-531) in Qingdao, China.

- CNS Xiamen (FFG-515) in Taizhou, China.

- HMS President in London, England.

- HMS Wellington in London, England.

- HNoMS Narvik in Horten, Norway.

- KD Hang Tuah in Lumut, Malaysia.

See also

- Frigate 36, a sailboat design, named in honour of the warship class

- List of escorteurs of the French Navy

- List of frigate classes

- List of frigate classes by country

- List of frigates of World War II

- United States Navy 1975 ship reclassification

References

Citations

- Henderson, James: Frigates Sloops & Brigs. Pen & Sword Books, London, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-301-0.

- Rodger (2004) p. 216

- Geofrrey Parker, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West 1500–1800, p. 99

- Breen, Colin; Forsythe, Wes (2007). "The French Shipwreck La Surveillante, Lost in Bantry Bay, Ireland, in 1797". Historical Archaeology. 41 (3): 41–42. JSTOR 25617454.

- Gardiner and Lavery (1992), pp. 36–37

- Gardiner and Lavery (1992), p. 37

- Gardiner and Lavery (1992), p. 39

- Gardiner (2000), p. 19

- Gardiner and Lavery (1992), p. 153

- Gardiner (200), pp. 40–42

- Gardiner and Lavery (1992), p. 40

- Archibald, Roger. 1997. Six ships that shook the world. American Heritage of Invention & Technology 13, (2): 24.

- Gardiner (200), pp. 48–56

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793–1815. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 49, 298–300. ISBN 978-1-59114-611-7.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 17. p. 469.

- ARG. "Top 10 Frigates | Military-Today.com". www.military-today.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- prinzeugen.com "Frigate: An Online Photo Album". Archived 21 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on: 11 February 2008.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed., Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946, New York: Mayflower Books, 1980, ISBN 0-8317-0303-2, p. 149.

- Bauer and Roberts, pp. 215–217

- Bauer and Roberts, pp. 251–252

- Gardiner and Chumbley, pp. 580–585

- http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/operations-and-support/surface-fleet/type-23-frigates/ Archived 31 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Type 23 frigates at the Royal Navy website

- "De Zeven Provinciën classe (LCF)". Jaime Karreman. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Navy Frigate Warships". Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Larter, David (2 July 2014). "Decommissioning plan pulls all frigates from fleet by end of FY '15". Militarytimes.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- SNA: Modified Littoral Combat Ships to be Designated Frigates Archived 6 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine – News.USNI.org, 15 January 2015

Sources

- Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-26202-9.

- Bennett, G. (2001)The Battle of Trafalgar, Barnsley (2004). ISBN 1-84415-107-7.

- Constam, Angus & Bryan, Tony, British Napoleonic Ship-Of-The-Line, Osprey Publishing, 184176308X

- Gardiner, Robert (2000) Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars, Chatham Publishing, London.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chumbley, Stephen (1995). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1947–1995. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-132-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Lambert, Andrew, (Editors), (2001) Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship, 1815–1905 (Conway's History of the Ship series), Book Sales,

- Gardiner, Robert & Lavery, Brian (Editors) (1992) The Line of Battle: The Sailing Warship 1650–1840, Conway Maritime Press, London.

- Gresham, John D. "The swift and sure steeds of the fighting sail fleet were its dashing frigates", Military Heritage magazine, (John D. Gresham, Military Heritage, February 2002, Volume 3, No.4, pp. 12 to 17 and p. 87).

- Rodger, N. A. M. The Command of the Ocean, a Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, London (2004). ISBN 0-7139-9411-8

- Lambert, Andrew (1984) Battleships in Transition, the Creation of the Steam Battlefleet 1815–1860, published Conway Maritime Press, . ISBN 0-85177-315-X

- Lavery, Brian (1989) Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793–1815. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, . ISBN 1-59114-611-9.

- Lavery, Brian (1983) The Ship of the Line, Volume 1: The Development of the Battlefleet, 1650–1850. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-631-7.

- Lavery, Brian. (1984) The Ship of the Line, Volume 2: Design, Construction and Fittings. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-953-7.

- Mahan, A.T., (2007) The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660–1783, Cosimo, Inc.,

- Marriott, Leo. Royal Navy Frigates 1945–1983, Ian Allan, 1983, ISBN 0-7110-1322-5

- Macfarquhar, Colin & Gleig, George (eds.), ((1797)) Encyclopædia Britannica: Or, A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, London, Volume 17, Third Edition.

- Rodger, N.A.M. ((2004)) The Command of the Ocean, a Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, London . ISBN 0-7139-9411-8.

- Sondhaus, L. Naval Warfare, 1815–1914

- Winfield, Rif. (1997) The 50-Gun Ship. London: Caxton Editions, ISBN 1-84067-365-6, ISBN 1-86176-025-6.

- Lavery, B. (2004) Ship, Dorling Kindersly, Ltd . ISBN 1-4053-1154-1.

External links

| Look up frigate in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frigates. |

- Frigates from battleships-cruisers.co.uk – history and pictures of United Kingdom frigates since World War II

- Frigates from Destroyers OnLine – pictures, history, crews of United States frigates since 1963

- The Development of the Full-Rigged Ship From the Carrack to the Full-Rigger

.jpg)