Portobelo, Colón

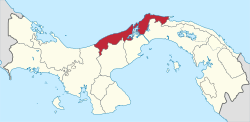

Portobelo (historically Porto Bello in English) is a port city and corregimiento in Portobelo District, Colón Province, Panama, with a population of 4,559 as of 2010.[1] Established during the Spanish colonial period, it functions as the seat of Portobelo District.[1] Located on the northern part of the Isthmus of Panama, it has a deep natural harbor and served as a center for silver exporting before the mid-eighteenth century and its destruction in 1739 during the War of Jenkins' Ear.

Portobelo | |

|---|---|

Corregimiento and city | |

Portobelo ruins and bay | |

Portobelo | |

| Coordinates: 9°33′00″N 79°39′00″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | Colón |

| District | Portobelo |

| Founded | 1597 |

| Founded by | Francisco Velarde y Mercado |

| Area | |

| • Land | 244.7 km2 (94.5 sq mi) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 4,559 |

| • Density | 18.6/km2 (48/sq mi) |

| Population density calculated based on land area. | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| Climate | Am |

It slowly rebuilt and the city's economy revived briefly in the late-nineteenth-century during the construction of the Panama Canal. In 1980, UNESCO designated the ruins of the Spanish colonial fortifications, along with nearby Fort San Lorenzo, as a World Heritage Site named Fortifications on the Caribbean Side of Panama: Portobelo-San Lorenzo.

History

Portobelo was colonized in 1597 by Spanish explorer Francisco Velarde y Mercado[2] and quickly replaced Nombre de Dios as a Caribbean port for Peruvian silver. Legend has it that Christopher Columbus originally named the port "Puerto Bello", meaning "Beautiful Port", in 1502.[3] After Francis Drake died of dysentery in 1596 at sea, he was said to be buried in a lead coffin near Portobelo Bay. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, it was an important silver-exporting port in New Granada on the Spanish Main and one of the ports on the route of the Spanish treasure fleets. The Spanish built defensive fortifications.

The privateer William Parker attacked and captured the city in 1601 and Captain Henry Morgan repeated the feat in 1668. He led a fleet of privateers and 450 men against Portobelo, which, in spite of its good fortifications, he captured. His forces plundered it for 14 days, stripping nearly all its wealth while raping, torturing and killing the inhabitants. It was captured again in 1680 by John Coxon[4]

The British had a disaster in the Blockade of Porto Bello under Admiral Hosier in 1726. As part of the campaigns of the War of Jenkins' Ear, the port was attacked on November 21, 1739, and captured by a British fleet of six ships, commanded by Admiral Edward Vernon. The British victory created an outburst of popular acclaim throughout the British Empire. More medals were struck for Vernon than for any other 18th-century British figure. Across the British Isles, Portobello was used in place and street names in honor of the victory, such as Portobello Road in London, the Portobello area in Edinburgh, and the Portobello Barracks in Dublin.[5]

The Spanish quickly recovered the Panamanian town and defeated Admiral Vernon in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias in 1741. Vernon was forced to return to England with a decimated fleet, having suffered more than 18,000 casualties.[6] Despite the Portobello campaign, British efforts to gain a foothold in the Spanish Main and disrupt the galleon trade were fruitless. Following the War of Jenkins' Ear, the Spanish switched from large fleets calling at few ports to small fleets trading at a wide variety of ports, developing a flexibility that made them less subject to attack. The ships also began to travel around Cape Horn to trade directly at ports on the western coast.

Today

Its population as of 1990 was 3,058; its population as of 2000 was 3,867.[1] In July 2012, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee placed Portobelo and nearby Fort San Lorenzo on the List of World Heritage in Danger, inscribed as Fortifications on the Caribbean Side of Panama: Portobelo-San Lorenzo, citing environmental factors, lack of maintenance, and uncontrollable urban developments.[7]

Gallery

Portobelo's Customs House

Portobelo's Customs House Main entrance to San Jeronimo Fort

Main entrance to San Jeronimo Fort Cannon battery at San Jeronimo Fort

Cannon battery at San Jeronimo Fort San Jeronimo Fort

San Jeronimo Fort Cannon battery of Santiago Fort

Cannon battery of Santiago Fort Entrance to Santiago Fort

Entrance to Santiago Fort San Lorenzo fort

San Lorenzo fort Cannon battery at San Lorenzo fort

Cannon battery at San Lorenzo fort

See also

- Iglesia de San Felipe

- Portobello, Edinburgh

- Portobello, Dublin

- Portobello Road, London

References

- "Cuadro 11 (Superficie, población y densidad de población en la República...)" [Table 11 (Area, population, and population density in the Republic...)] (.xls). In "Resultados Finales Básicos" [Basic Final Results] (in Spanish). National Institute of Statistics and Census of Panama. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- Shirley Fish (17 May 2011). The Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific with an Annotated List of the Transpacific Galleons 1565-1815. AuthorHouse. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-4567-7542-1. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Patricia Katzman (10 February 2006). Panama. Hunter Publishing, Inc. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-1-58843-529-3. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Rogoziński, Jan (1997). The Wordsworth dictionary of pirates. Ware: Wordsworth Reference. p. 266. ISBN 1-85326-384-2.

- Brendan Simms (8 December 2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714-1783. Basic Books. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-465-01332-6. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Duncan, Francis. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, London, 1879, Vol.1, p.123, Quote:"...so reduced was this force in two years by disaster and disease, that not a tenth part returned to England...'thus ended in shame, disappointment, and loss, the most important, most expensive, and best concerted expedition that Great Britain was ever engaged in'...".

- Panamanian Fortifications Added to UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger Archived 2015-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, Global Heritage Fund blog article

Bibliography

- Rodger, N. A. M. The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portobelo. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Portobelo. |