Anti-Chinese sentiment

Anti-Chinese sentiment or Sinophobia (from Late Latin Sinae "China" and Greek φόβος, phobos, "fear") is a sentiment against China, its people, overseas Chinese, or Chinese culture.[5] It often targets Chinese minorities living outside of China and involves immigration, development of national identity in neighbouring countries, disparity of wealth, the past central tributary system, majority-minority relations, imperial legacies, and racism.[6][7][8] Its opposite is Sinophilia.

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Neutral | Pos-Neg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

14% | 85% | 1 | –71 | |

25% | 70% | 5 | –45 | |

27% | 67% | 6 | –40 | |

26% | 60% | 14 | –34 | |

27% | 57% | 16 | –30 | |

33% | 62% | 5 | –29 | |

34% | 63% | 3 | –29 | |

35% | 61% | 4 | –26 | |

34% | 56% | 10 | –22 | |

36% | 58% | 6 | –22 | |

36% | 57% | 7 | –21 | |

37% | 57% | 6 | –20 | |

38% | 55% | 7 | –17 | |

39% | 53% | 8 | –14 | |

42% | 54% | 4 | –12 | |

40% | 48% | 12 | –8 | |

36% | 36% | 28 | 0 | |

40% | 37% | 23 | +3 | |

46% | 35% | 19 | +11 | |

45% | 33% | 22 | +12 | |

47% | 34% | 19 | +13 | |

51% | 32% | 17 | +19 | |

47% | 24% | 29 | +23 | |

51% | 27% | 22 | +24 | |

50% | 22% | 28 | +28 | |

58% | 25% | 17 | +33 | |

55% | 20% | 25 | +35 | |

66% | 25% | 9 | +41 | |

57% | 14% | 29 | +43 | |

68% | 22% | 10 | +46 | |

63% | 16% | 21 | +47 | |

70% | 17% | 13 | +53 | |

71% | 18% | 11 | +53 |

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Pos-Neg |

|---|---|---|---|

15% | 68% | –53 | |

22% | 70% | –48 | |

19% | 60% | –41 | |

29% | 54% | –25 | |

35% | 60% | –25 | |

28% | 50% | –22 | |

37% | 58% | –21 | |

20% | 35% | –15 | |

37% | 51% | –14 | |

46% | 47% | –1 | |

| World (excl. China) | 41% | 42% | –1 |

45% | 38% | 7 | |

37% | 25% | 12 | |

49% | 34% | 15 | |

44% | 23% | 21 | |

55% | 26% | 29 | |

63% | 27% | 36 | |

63% | 12% | 51 | |

83% | 9% | 74 | |

88% | 10% | 78 |

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Pos-Neg |

|---|---|---|---|

25% | 69% | –44 | |

21% | 63% | –42 | |

24% | 61% | –37 | |

26% | 61% | –35 | |

31% | 64% | –33 | |

29% | 60% | –31 | |

29% | 59% | –30 | |

32% | 60% | –28 | |

32% | 59% | –27 | |

34% | 61% | –27 | |

34% | 57% | –23 | |

36% | 55% | –19 | |

30% | 47% | –17 | |

41% | 53% | –12 | |

37% | 48% | –11 | |

40% | 50% | –10 | |

36% | 45% | –9 | |

36% | 44% | –8 | |

39% | 47% | –8 | |

45% | 49% | –4 | |

39% | 41% | –2 | |

43% | 35% | 8 | |

49% | 36% | 13 | |

54% | 39% | 15 | |

47% | 31% | 16 | |

56% | 34% | 22 | |

51% | 29% | 22 | |

58% | 27% | 31 |

Statistics and background

In 2013, Pew Research Center from the United States conducted a survey over Sinophobia, finding that China was viewed favorably in half (19 of 38) of the nations surveyed, excluding China itself. Beijing's strongest supporters were in Asia, in Malaysia (81%) and Pakistan (81%); African nations of Kenya (78%), Senegal (77%) and Nigeria (76%); as well as Latin America, particularly in countries heavily engaging with the Chinese market, such as Venezuela (71%), Brazil (65%) and Chile (62%).[9] However, anti-China sentiment has remained permanent in the West and other Asian countries: only 28% of Germans and Italians and 37% of Americans viewed China favorably while in Japan, just 5% of respondents had a favorable opinion of the country. But in just 11 of the 38 nations surveyed was China actually viewed unfavorably by at least half of those surveyed. Japan was polled to have the most anti-China sentiment, where 93% see the People's Republic in a negative light, including 48% of Japanese who have a very unfavorable view of China. There were also majorities in Germany (64%), Italy (62%) and Israel (60%) who held negative views of China. The rise in anti-China sentiment in Germany was particularly striking: from 33% disfavor in 2006 to 64% under the 2013 survey, with such views existing despite Germany's success exporting to China.[9]

Despite China's general appeal to the young, half or more of those people surveyed in 26 of 38 nations felt that China acted unilaterally in international affairs, notably increasing tensions between China and other neighboring countries, excluding Russia, over territorial disputes. This concern about Beijing's failure to consider other countries' interests when making foreign policy decisions was particularly strong in the Asia-Pacific – in Japan (89%), South Korea (79%) and Australia (79%) – and in Europe – in Spain (85%), Italy (83%), France (83%) and Britain (82%). About half or more of those in the seven Middle Eastern nations surveyed also thought China acted unilaterally. This includes 79% of Israelis, 71% of Jordanians and 68% of Turks. There was relatively less concern about this issue in the U.S. (60%). African nations – in particular strong majorities in Kenya (77%), Nigeria (70%), South Africa (67%) and Senegal (62%) – believed Beijing considered their interests when making foreign policy decisions.[9] When asked in 2013 whether China had the respect it should have, 56% of Chinese respondents felt China should have been more respected.[9]

History

While historical accords have indicated longer anti-Chinese hostilities throughout China's imperial wars,[10] the modern Sinophobia only began from the 19th century onward.

At the time of the British Empire's First Opium War (1839-1842) against Qing China, Lord Palmerston regarded the Chinese as uncivilized and suggested that the British must attack China to show up their superiority as well as to demonstrate what a "civilized" nation could do.[11] The trend became commonly popular throughout the Second Opium War (1856-1860), when repeated attacks against foreign traders in China inflamed anti-Chinese campaigns. With the defeat of China in both wars, and violent behavior of Chinese towards foreigners, Lord Elgin upon his arrival in Peking in 1860 ordered the looting and burning of China's Summer Palace in vengeance, highlighting the deep Sinophobic sentiment existing in the West.[12]

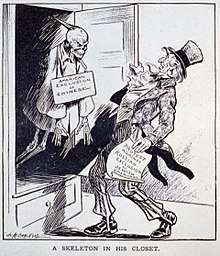

In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act further deepened Sinophobic sentiment in the U.S., which escalated into tensions. Chinese workers were forbidden and treated as second-class citizens.[13] Meanwhile, during the mid-19th century in Peru, Chinese were used as slave laborers and they were not allowed to hold any positions in Peruvian society.[14]

On the other hand, the Empire of Japan was also known for its strong Sinophobia. After the violence in Nagasaki caused by Chinese sailors, it stemmed anti-Chinese sentiment in Japan and following Qing China's non-apology, it even strained further. After the end of the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan defeated China and soon acquired colonial possessions of Taiwan and Ryukyu Islands.

Throughout the 1920s, Sinophobia was still common in Europe, notably in Britain. Chinese men had been a fixture on London's docks since the mid-eighteenth century, when they arrived as sailors who were employed by the East India Company, importing tea and spices from the Far East. Conditions on those long voyages were so dreadful that many sailors decided to abscond and take their chances on the streets rather than face the return journey. Those who stayed generally settled around the bustling docks, running laundries and small lodging houses for other sailors or selling exotic Asian produce. By the 1880s, a small but recognizable Chinese community had developed in the Limehouse area, to the consternation of white native-born Londoners, who feared racial mixing and an influx of cheap labor. The entire Chinese population of London was only in the low hundreds—in a city whose entire population was roughly estimated to be seven million—but nativist feelings ran high, as was evidenced by the Aliens Act of 1905, a bundle of legislation which sought to restrict entry to poor and low-skilled foreign workers.[15] Chinese also had to work as robbers to drug dealers.[15]

World War II era massacres like the Nanking Massacre and widespread human rights abuses caused rifts between China and Japan which still exist today.[16]

During the Cold War, anti-Chinese sentiment became permanent in the media of the Western world and anti-communist countries, largely after the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. From the 1950s to the 1980s, anti-Chinese sentiment was so high in Korea, where the Korean War was fought and the Chinese subsequently intervened against South Korea. To this day, many Koreans believe that China perpetrated the division of Korea into two countries.[17]

Even in the Soviet Union, anti-Chinese sentiment was so high due to the differences which existed between China and the USSR which nearly resulted in war between the two countries. The "Chinese threat" as it was described in a letter by Alexander Solzhenitsyn prompted expressions of anti-Chinese sentiment in the conservative Russian samizdat movement.[18] Since the 1990s, China's economic reforms have turned the country into a global power. Nonetheless, distrust of China and Chinese is sometimes attributed to the backlash which exists against the historical memory of Sinicization which was first pursued by Imperial China and was later pursued by the Republic of China, and the additional backlash which exists against the modern policies of the Chinese government, both of which are permanent in many countries like India, Korea, Japan and Vietnam.[19][20] Another reason is China's attempt to whitewash history of not just China but also of neighboring countries to portray itself as an innocent victim in relationship with majority of countries bordering China, with the exception of Pakistan and Russia, that further boosted anti-Chinese sentiment.[21]

Regional antipathy

East Asia

Japan

After the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II in 1945, the relationship between China and Japan gradually improved. However, since 2000, Japan has seen a gradual resurgence of anti-Chinese sentiment. Many Japanese believe that China is using the issue of the countries' checkered history, such as the Japanese history textbook controversies, many past war crimes committed by Japan's military, and official visits to the Yasukuni Shrine (in which a number of war criminals are enshrined), as both a diplomatic card and a tool to make Japan a scapegoat in domestic Chinese politics.[22] The Anti-Japanese Riots in the Spring of 2005 were another source of more anger towards China among the Japanese public. Anti-Chinese sentiments have been on a sharp rise in Japan since 2002. According to the Pew Global Attitude Project (2008), 84% of Japanese people held an unfavorable view of China and 73% of Japanese people held an unfavorable view of Chinese people, which was a higher percentage than all the other countries surveyed.[23]

A survey in 2017 suggested that 51% of Chinese respondents had experienced tenancy discrimination.[24] Another report in the same year noted a significant bias against Chinese visitors from the media and some of the Japanese locals.[25]

Korea

Korea has had a long history of both resistance against and subordination to China.[26][27] Until the arrival of Western imperialism in the 19th century, Korea had been part of the sinocentric East Asian regional order.[28] In the early 2000s, a dispute over the history of Goguryo, which both Koreas and China claim as their own, caused tension between the two countries.[28]

In 1931, while Korea was dominated by Imperial Japan, there was a dispute between Chinese and Korean farmers in Wanpaoshan, Manchuria. It was highly sensationalized in the Japanese and Korean press, and used as propaganda to increase anti-Chinese sentiment. It caused a series of anti-Chinese riots throughout Korea, starting in Incheon on July 3 and spreading rapidly to other cities. Chinese sources estimate that 146 people were killed, 546 wounded, and a considerable number of properties were destroyed. The worst riot occurred in Pyongyang on July 5. In this effect, the Japanese had a considerable influence on sinophobia in Korea.[29]

Starting in October 1950, the People's Volunteer Army fought in the Korean War (1950–1953) on the side of North Korea against South Korean and United Nations troops. The participation of the PVA made the relations between South Korea and China hostile. Throughout the Cold War, there were no official relations between capitalist South Korea and communist China until August 24, 1992, when formal diplomatic relations were established between Seoul and Beijing.

Anti-Chinese sentiments in South Korea have been on a steady rise since 2002. According to Pew opinion polls, favorable view of China steadily declined from 66% in 2002 to 48% in 2008, while unfavorable views rose from 31% in 2002 to 49% in 2008.[30] According to surveys by the East Asia Institute, positive view of China's influence declined from 48.6% in 2005 to 38% in 2009, while negative view of it rose from 46.7% in 2005 to 50% in 2008.[31]

Relations further strained with the deployment of THAAD in South Korea in 2017, in which China started its boycott against Korea, making Koreans to develop anti-Chinese sentiment in South Korea over reports of economic retaliation by Beijing.[32] According to a poll from the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies at Seoul National University in 2018, 46 percent of South Koreans found China as the most threatening country to inter-Korean peace (compared to 33 percent for North Korea), marking the first time China was seen as a bigger threat than North Korea since the survey began in 2007.[33]

Discriminatory views of Chinese people have been reported or implied in some sources,[34][35] and ethnic-Chinese Koreans have faced prejudices including what is said to be a widespread criminal stigma.[36][37][38]

Hong Kong

.jpg)

Although Hong Kong's sovereignty was transferred to China in 1997, only a small minority of its inhabitants consider themselves to be exclusively and simply Chinese. According to a survey that was conducted by the University of Hong Kong in December 2014, 42.3% of respondents identified themselves as "Hong Kong citizens", versus only 17.8% who identified themselves as "Chinese citizens", and 39.3% who chose to give themselves a mixed identity (a Hong Kong Chinese or a Hong Konger who was living in China).[39] The number of mainland Chinese visitors to the region has surged since the handover, reaching 28 million in 2011. The influx is perceived by many locals to be the cause of their housing and job difficulties. Negative perceptions have been exacerbated by posts and recirculations of alleged mainlander misbehaviour on social media,[40] as well as noted bias in major HK newspapers.[41][42][43] In 2013, polls from the University of Hong Kong suggested that 32 to 35.6 per cent of locals had "negative" feelings for mainland Chinese people.[44] However, a 2019 survey of Hong Kong residents has suggested that there are also some who attribute positive stereotypes to visitors from the mainland.[45][46]

In 2012, a group of Hong Kong residents published a newspaper advertisement depicting mainland visitors and immigrants as locusts.[47] In February 2014, about 100 Hong Kongers harassed mainland tourists and shoppers during what they styled an "anti-locust" protest in Kowloon. In response, the Equal Opportunities Commission of Hong Kong proposed an extension of the territory's race-hate laws to cover mainlanders.[48] Strong anti-mainland sentiment has also been documented amidst the 2019 protests,[49] with reported instances of protesters attacking Mandarin-speakers and mainland-linked businesses.[50][51][52][53]

Mongolia

Inner Mongolia used to be part of Greater Mongolia, until Mongolia was absorbed into China at 17th century following the Qing conquest. For three centuries, Mongolia was marked with little interests even during the expansion of Russian Empire. With the Qing collapse, China attempted to retake Mongolia only to see its rule fallen with the Mongolian Revolution of 1921, overthrowing the Chinese rule; but it was proposed that Zhang Zuoling's domain (the Chinese "Three Eastern Provinces") take Outer Mongolia under its administration by the Bogda Khan and Bodo in 1922 after pro-Soviet Mongolian Communists seized control of Outer Mongolia.[54] However, China failed to take Outer Mongolia (which would become modern Mongolia) but successfully maintained their presence in Inner Mongolia. For this reason, it has led to a strong anti-Chinese sentiment among the native Mongol population in Inner Mongolia which have rejected assimilation, which prompted Mongolian nationalists and Neo-Nazi groups to be hostile against China.[55] One of the most renown unrest in modern China is the 2011 Inner Mongolia unrest, following the murder of two ethnic Mongolians in separate incidents.[56] Mongolians traditionally hold very unfavorable views of China.[57] The common stereotype is that China is trying to undermine Mongolian sovereignty in order to eventually make it part of China (the Republic of China has claimed Mongolia as part of its territory, see Outer Mongolia ). Fear and hatred of erliiz (Mongolian: эрлийз, [ˈɛrɮiːt͡sə], literally, double seeds), a derogatory term for people of mixed Han Chinese and Mongol ethnicity,[58] is a common phenomena in Mongolian politics. Erliiz are seen as a Chinese plot of "genetic pollution" to chip away at Mongolian sovereignty, and allegations of Chinese ancestry are used as a political weapon in election campaigns – though not always with success.[59][60] Several Neo-Nazi groups opposing foreign influence, especially China's, are present within Mongolia.[61]

Taiwan

Due to historical reasons dating back to the de facto end of the Chinese Civil War, the relationship between the two majority ethnic Chinese and Mandarin Chinese-speaking regions has been tense due to the fact that the People's Republic of China has threatened repeatedly to invade if Taiwan were to declare independence, shedding the status quo of existing legally as the Republic of China and replacing a Chinese national identity with a distinctly Taiwanese identity. This creates strong divisions between mainland China and Taiwan[62] and further strains the relationship between two nations.

Anti-Chinese sentiment in Taiwan also comes from the fact that many Taiwanese, especially those in their 20s, choose to identify solely as "Taiwanese",[63] and are against having closer ties with the Chinese mainland, like those in the Sunflower Student Movement.[64] A number of Taiwanese have also viewed mainlanders as backwards or uncivilised, according to Peng Ming-min, a Taiwanese politician.[65]

According to a 2020 survey 76% of Taiwanese consider China to be "unfriendly" towards Taiwan.[66]

Central Asia

Afghanistan

Recently, the Xinjiang conflict has strained the relations between Afghanistan and China.[67]

Kazakhstan

In 2018 massive land reform protests were held in Kazakhstan. The protesters demonstrated against leasing land to Chinese companies and the perceived economic dominance of Chinese companies and traders.[68][69] Other issues leading to rise of Sinophobia in Kazakhstan is also over the Xinjiang conflict and Kazakhstan hosting a significant number of Uyghur separatists.

Tajikistan

Resentment against China and Chinese also increased in Tajikistan recent years due to accusation of China's land grab from Tajikistan.[70] In 2013, Tajik Popular Social-Democrat Party leader, Rakhmatillo Zoirov, claimed Chinese troops were entering to Tajikistan deeper than it got from land ceding.[71]

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan is traditionally non-aligned and somewhat positive of China. There are historical grievances, however, such as occupation by Qing China, ethnic cleansing. A Kyrgyz farmer claimed "We always run the risk of being colonized by the Chinese,", in fear of future being colonized by China.[72] Meanwhile, like in other Central Asian nations, Kyrgyz people mostly sympathize with Uyghur separatism in China, further complicated relations.[72]

Within mainland China

Xinjiang

After China took over control of Xinjiang under Mao Zedong to establish the PRC in 1949, there have been considerable ethnic tensions arising between the Han Chinese and Turkic Muslim Uyghurs.[73][74][75][76][77] This manifested itself in the 1997 Ghulja incident,[78] the bloody July 2009 Ürümqi riots,[79] and the 2014 Kunming attack.[80] This has prompted China to suppress the native population and create re-education camps for purported counter-terrorism efforts, which have reportedly fuelled resentment in the region.[81][82] Al Jazeera has reported that many Uighurs during the COVID-19 pandemic felt the virus is a divine punishment against China.[83]

Tibet

Tibet has a complicated relations with China. Both are part of the Sino-Tibetan language family and share a long history. Tang dynasty and Tibetan Empire did enter into a military conflict. and had a major effect on the rise of Sinophobia among Tibetans. In the 13th century, Tibet fell into the rule of Yuan dynasty but it soon broke out with the collapse of Yuan dynasty. Relationship between Tibet with China remains complicated until Tibet was invaded again by the Qing dynasty. Following the British expedition to Tibet at 1904, many Tibetans look back to it as an exercise of Tibetan self-defence and an act of independence from the Qing dynasty as the dynasty was falling apart.[84] and has left a dark chapter in their modern relations. The Republic of China failed to reconquer Tibet but the later People's Republic of China retook Tibet and incorporated it as Tibet Autonomous Region within China. Despite 14th Dalai Lama and Mao Zedong had together signed Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, China was accused for not honoring the treaty[85] and led to 1959 Tibetan uprising which was totally suppressed by China[86] and Dalai Lama escaped to India.[87]

Tibetans once again rioted against Chinese rule twice, the 1987–89 unrest[88] and 2008 unrest, where they directed their angers against Han and Hui Chinese.[89] Both have been suppressed by China and China has increased their military presence in the region, despite self-immolations against China are still ongoing.[90]

Southeast Asia

Singapore

To counteract the city state's low birthrate, Singapore's government has been offering financial incentives and a liberal visa policy to attract an influx of migrants. Chinese immigrants to the nation grew from 150,447 in 1990 to 448,566 in 2015 to make up 18% of the foreign-born population, next to Malaysian immigrants at 44%.[91][92] The xenophobia towards mainland Chinese is reported to be particularly severe compared to other foreign residents,[93] as they are generally looked down on as country bumpkins and blamed for stealing desirable jobs and driving up housing prices.[94] There have also been reports of housing discrimination against mainland Chinese tenants,[95] and a 2019 YouGov poll has suggested Singapore to have the highest percentage of locals prejudiced against Chinese travellers out of the many countries surveyed.[96][97]

Malaysia

Due to race-based politics and Bumiputera policy, there had been several incidents of racial conflict between the Malays and Chinese before the 1969 riots. For example, in Penang, hostility between the races turned into violence during the centenary celebration of George Town in 1957 which resulted in several days of fighting and a number of deaths,[98] and there were further disturbances in 1959 and 1964, as well as a riot in 1967 which originated as a protest against currency devaluation but turned into racial killings.[99][100] In Singapore, the antagonism between the races led to the 1964 Race Riots which contributed to the expulsion of Singapore from Malaysia on August 9, 1965. The 13 May Incident probably the highest race riot happen in Malaysia with more than 143 or suggested 600 killed, mostly Chinese.

It was reported in 2019 that relations between ethnic Chinese Malaysians and indigenous Malays were "at their lowest ebb", and fake news posted online of mainland Chinese indiscriminately receiving citizenship in the country had been stoking racial tensions. The primarily Chinese-based Democratic Action Party in Malaysia has also reportedly faced an onslaught of fake news depicting it as unpatriotic, anti-Malay and anti-Muslim.[101] Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been social media posts claiming the initial outbreak is "divine retribution" for China's treatment of its Muslim Uygur population.[102]

Cambodia

During the late 1960s an estimated 425,000 ethnic Chinese lived in Cambodia. By 1984, as a result of the Khmer Rouge genocide and emigration, only about 61,400 Chinese remained in the country.[103][104][105]

The hatred for Chinese was projected on the ethnic Chinese of Cambodia during 80s. A Vietnamese report had noted "In general, the attitude of young people and intellectuals is that they hate Cambodian-Chinese."[106]

Recent influx of Chinese investment, especially in Sihanoukville Province, has led to rising anti-Chinese rhetoric.[107]

Philippines

The Spanish introduced the first anti-Chinese laws in the Philippine archipelago. The Spanish massacred or expelled Chinese several times from Manila, and the Chinese responded by fleeing to the Sulu Sultanate and supporting the Moro Muslims in their war against the Spanish. The Chinese supplied the Moros with weapons and joined them in fighting the Spanish directly during the Spanish–Moro conflict.

The standoff in Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal between China and the Philippines contributes to anti-China sentiment among Filipinos. Campaigns to boycott Chinese products began in 2012. People protested in front of the Chinese Embassy and it had led the Chinese embassy to issue travel warning for its citizens to the Philippines for a year.[108]

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, scholar Jonathan Corpus Ong has lamented that there is a great deal of hateful and racist speech on Filipino social media which "many academics and even journalists in the country have actually justified as a form of political resistance" to the Chinese government. There have been jokes and memes reposted of supposedly Chinese people defecating in public.[109]

Indonesia

The Dutch introduced anti-Chinese laws in the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch colonialists started the first massacre of Chinese in the 1740 Batavia massacre in which tens of thousands died. The Java War (1741–43) followed shortly thereafter.[110][111][112][113][114][115]

The asymmetrical economic position between ethnic Chinese Indonesians and indigenous Indonesians has incited anti-Chinese sentiment among the poorer majorities. During the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, in which more than 500,000 people died (mostly non-Chinese Indonesians),[116] ethnic Chinese were killed and their properties looted and burned as a result of anti-Chinese racism on the excuse that Dipa "Amat" Aidit had brought the PKI closer to China.[117][6] In the May 1998 riots of Indonesia following the fall of President Suharto, many ethnic Chinese were targeted by Indonesian rioters, resulting in a large number of looting. However, most of the deaths suffered when Chinese owned supermarkets were targeted for looting were not Chinese, but the Indonesian looters themselves, who were burnt to death by the hundreds when a fire broke out.[118][119]

In recent years, China's increasing aggression in South China Sea has led to the renewal of tensions, although Indonesia is much a latecomer. At first, the conflict stemmed mostly between China to Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia, with Indonesia chose to stay neutral but soon escalated when China attempted to claim Natuna Regency from Indonesia, in which triggered outrages in Indonesia.[120] However, there are also accusation about Indonesia's lack of activities to protect its fishermen from China's increasing aggressive behaviors also led to the deterioration of China's image in Indonesia.[121]

Myanmar

Although both countries share the exact same ancestor, the infamous 1967 riots in Burma against the Chinese community had sparked angers among Chinese, led to the arming of ethnic and political rebels by China against Burma. In the present day, resentment towards Chinese investments[122][123] and their perceived exploitation of natural resources have also hampered the Sino-Burmese relationship.[124] Chinese people in Myanmar have also been subject to discriminatory laws and rhetoric in Burmese media and popular culture.[125]

Thailand

Historically, Thailand and previous Siam is and was seen as China-friendly country, owning by the fact China and Siam enjoyed a close relations, a large portion of Thai population have Chinese descent and strong cooperation, with Thai Chinese have been assimilated to mainstream Thai society. However, at the 20th century, Plaek Phibunsongkhram launched a massive Thaification, including oppression of Thailand's Chinese population and hampered Thai Chinese communities, banning teaching Chinese language, and forcing them to adopt Thai names.[126] Plaek's obsession toward creating a pan-Thai nationalist agenda caused heavy resentment by Thai Chinese until he was removed at 1944.[127] After that, Thai Chinese do not experience anti-Chinese incidents, although the Cold War almost inflamed hostility toward Chinese community in Thailand.

Hostility towards the mainland Chinese increased with the influx of visitors from China in 2013.[128][129] It has also been worsened by Thai news reports and social media postings on misbehaviour from a portion of the tourists,[130] with the accuracy of some of the postings in dispute.[131][132] In spite of this, two reports have suggested that there are still some Thais who have positive impressions of Chinese tourists.[133][134]

Vietnam

Although both nations share a similar culture, there are strong anti-Chinese sentiments among the Vietnamese population, due in part to a past thousand years of Chinese rule in Northern Vietnam, a later series of Sino-Vietnamese wars in the history between two nations and recent territory disputes in the Paracel and Spratly Islands.[135][136][137] Though current relations are peaceful, numerous wars fought between the two nations in the past, from the time of Early Lê Dynasty (10th century)[138] to the Sino-Vietnamese War from 1979 to 1989. The conflict fueled racist discrimination against and consequent emigration by the country's ethnic Chinese population. From 1978 to 1979, some 450,000 ethnic Chinese left Vietnam by boat (mainly former South Vietnam citizens fleeing the Vietcong) as refugees or were expelled across the land border with China.[139] These mass emigrations and deportations only stopped in 1989 following the Đổi mới reforms in Vietnam.

Anti-Chinese sentiments had spiked in 2007 after China formed an administration in the disputed islands,[136] in 2009 when the Vietnamese government allowed the Chinese aluminium manufacturer Chinalco the rights to mine for bauxite in the Central Highlands,[140][141][142] and when Vietnamese fishermen were detained by Chinese security forces while seeking refuge in the disputed territories.[143] In 2011, following a spat in which a Chinese Marine Surveillance ship damaged a Vietnamese geologic survey ship off the coast of Vietnam, some Vietnamese travel agencies boycotted Chinese destinations or refused to serve customers with Chinese citizenship.[144] Hundreds of people protested in front of the Chinese embassy in Hanoi and the Chinese consulate in Ho Chi Minh City against Chinese naval operations in the South China Sea before being dispersed by the police.[145] In May 2014, mass anti-Chinese protests against China moving an oil platform into disputed waters escalated into riots in which many Chinese factories and workers were targeted. In 2018, thousands of people nationwide protested against a proposed law regarding Special Economic Zones that would give foreign investors 99 year leases on Vietnamese land, fearing that it would be dominated by Chinese investors.[146]

According to journalist Daniel Gross, Sinophobia is omnipresent in modern Vietnam, where "from school kids to government officials, China-bashing is very much in vogue." He reports that a majority of Vietnamese resent the import and usage of Chinese products, considering them distinctly low status.[147] A 2013 book on varying host perceptions in global tourism has also referenced negativity from Vietnamese hosts towards Chinese tourists, where the latter were seen as "making a lot more requests, complaints and troubles than other tourists"; the views differed from the much more positive perceptions of young Tibetan hosts at Lhasa towards mainland Chinese visitors in 2011.[148][149]

South Asia

Nepal

The relationship between two only began in the 18th century when the Qing dynasty expanded near the Nepalese border, but this resulted in war between two nations, at the time concentrated mostly in Tibet.[150] After the war, Nepal and China signed a peace treaty, which made Nepal a vassal of China; but with the Anglo-Nepalese War and China's failure to assist Nepal, it inflamed the hatred, and Nepal contributed Gorkha troops to help the British fighting China in the Opium Wars.[151]

In modern relations, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Nepalese media, most notably Kathmandu Post, has published questions regarding Chinese transparency, and accused the Chinese government of open threat against Nepal due to its report, which hampers the relationship between two.[152] It became further complicated after CCTV's foreign outlet CGTN published on Twitter a tweet about the Mount Everest and called it Mount Qomolangma in the Tibetan language (Tibet is currently part of China), which caused widespread enrages from the Nepalese public that China is trying to claim the mount from Nepal.[153]

Bhutan

The relation between Bhutan and China has historically been tense and past events have led to anti-Chinese sentiment within the country. Notably the Chinese government's destruction of Tibetan Buddhist institutions in Tibet in 1959 led to a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment in the country.[154] Similarly, the publishing of a controversial map in the book, A Brief History of China which illustrated a large portion of Bhutanese territory belonging to China and the statement released by China in 1960 which claimed the Bhutanese "form a united family in Tibet" and "they must once again be united and taught the communist doctrine" all led to hostile responses from Bhutan including the closing of its border, trade and all diplomatic contact with China. Bhutan and China have not established diplomatic relations.[155]

Sri Lanka

Although there is a lot of favorable opinions about China because they helped to finish the civil war in Sri Lanka there are anti-Chinese sentiment among some people over Chinese investment in the country.[156][157][158]

India

During the Sino-Indian War, the Chinese faced anti-national sentiment unleashed by the Indian National Congress-dominated government. Chinese businesses were investigated for links to the Chinese government and many people of Chinese origin were interned in prisons in North India.[159] The Indian government passed the Defence of India Act in December 1962,[160] permitting the "apprehension and detention in custody of any person [suspected] of being of hostile origin." The broad language of the act allowed for the arrest of any person simply for having a Chinese surname or a Chinese spouse.[161] The Indian government incarcerated thousands of Chinese-Indians in an internment camp in Deoli, Rajasthan, where they were held for years without trial. The last internees were not released until 1967. Thousands more Chinese-Indians were forcibly deported or coerced to leave India. Nearly all internees had their properties sold off or looted.[160] Even after their release, the Chinese Indians faced many restrictions in their freedom. They could not travel freely until the mid-1990s.[160]

On 2014, India in conjunction with Tibet have called for a joint campaign to boycott Chinese goods due to border intrusion incidents. Similarly to the Philippines and Vietnam the call for the boycott of Chinese goods by India is related to the contested territorial disputes India has with China.[162][163]

The 2020 China–India skirmishes killed 20 Indian soldiers, in hand-to-hand combat with Chinese troops using barbed wire bats. No specific casualties numbers were represented from China, though they acknowledged they had experienced deaths. India claims the deaths of 40-45 Chinese soldiers.[164]

Following the skirmishes, a company from Jaipur, India developed an app named "Remove China Apps" and released it on the Google Play Store, gaining 5 millon downloads in less than 2 weeks. It discouraged software dependance on China and promoted apps developed in India. Following the 2020 skirmishes, people were concerned about their privacy. Amid tensions, TikTok began censoring anti-China content on its platform and banning users, prompting people to uninstall apps like SHAREit, ES File Explorer etc.[165]

Pacific Islands

Papua New Guinea

In May 2009, Chinese-owned businesses were pillaged by looters in several cities across Papua New Guinea, amid increasing anti-Chinese sentiment reported in the country.[166] Thousands of people were reportedly involved in the riots.[167]

Tonga

In 2000, Tongan noble Tu'ivakano of Nukunuku banned Chinese stores from his Nukunuku District in Tonga. This followed complaints from other shopkeepers regarding competition from local Chinese.[168] In 2001, Tonga's Chinese community (a population of about three or four thousand people) was hit by a wave racist assaults. The Tongan government did not renew the work permits of more than 600 Chinese storekeepers, and has admitted the decision was in response to "widespread anger at the growing presence of the storekeepers".[169]

In 2006, rioters damaged shops owned by Chinese-Tongans in Nukuʻalofa.[170][171]

Solomon Islands

In 2006, Honiara's Chinatown suffered damage when it was looted and burned by rioters following a contested election. Ethnic Chinese businessmen were falsely blamed for bribing members of the Solomon Islands' Parliament. The government of Taiwan was the one that supported the then current government of the Solomon Islands. The Chinese businessmen were mainly small traders from mainland China and had no interest in local politics.[170]

Eurasia, former Soviet Union and the Middle East

Israel

Israel and China are seen to have a friendly relationship, and a 2018 survey suggests that a significant percentage of the Israeli population have a positive view of the Chinese culture and people.[172] It is also historically preceded by the support from local Chinese to Jewish refugees fleeing from Nazi persecution amidst the World War II.[173] The Jews also gained praise on their successful integration within the mainstream Chinese society.[174]

However, the rise of communist China made the relationship less positive. The rise of Xi Jinping hampered the relations, with the Jews suffering a crackdown since 2016, which has been reported in Israeli media.[175][176] This has led to some Sinophobic sentiments in Israel, with Israeli nationalists viewing China a despotic and authoritarian regime, given the ongoing repression of Jews in China.[175]

Another problem in regard to the struggling relationship is Israel's lack of trust in China, given China's strong tie to Iran, which is also viewed as a despotic nation and accusation that China is backing Iran against Israel, including the COVID-19 pandemic, had led to the deterioration of the positive image of China.[177]

Russia

After the Sino-Soviet split the Soviet Union produced propaganda which depicted the PRC and the Chinese people as enemies. In Central Asia Soviet propaganda specifically framed the PRC as an enemy of Islam and all Turkic peoples. These phobias have been inherited by the post-Soviet states in Central Asia.[178]

Russia inherited a long-standing dispute over territory with China over Siberia and the Russian Far East with the breakup of the Soviet Union, these disputes were formerly resolved in 2004. Russia and China no longer have territorial disputes and China does not claim land in Russia; however, there has also been a perceived fear of a demographic takeover by Chinese immigrants in sparsely populated Russian areas.[179][180] Both nations have become increasingly friendlier however, in the aftermath of the 1999 US bombing of Serbia, which the Chinese embassy was struck with a bomb, and have become increasingly united in one similar stance of hatred on the West, with both countries are being besieged.[181][182]

A 2019 survey of online Russians has suggested that in terms of sincerity, trustfulness, and warmth, the Chinese are not viewed especially negatively or positively compared to the many other nationalities and ethnic groups in the study.[183][184]

Turkey

On July 4, 2015, a group of around 2,000 Turkish ultra-nationalists from the Grey Wolves linked to MHP protesting against China's fasting ban in Xinjiang mistakenly attacked South Korean tourists in Istanbul,[185][186] which led to China issuing a travel warning to its citizens traveling to Turkey.[187] A Uyghur employee at a Chinese restaurant was beaten by the Turkish Grey Wolves-linked protesters. Devlet Bahçeli, a leader from Turkey's MHP (Nationalist Movement Party), said that the attacks by MHP affiliated Turkish youth on South Korean tourists was "understandable", telling the Turkish newspaper Hurriyet that: "What feature differentiates a Korean from a Chinese? They see that they both have slanted eyes. How can they tell the difference?".[188]

According to a November 2018 INR poll, 46% of Turks view China favourably, up from less than 20% in 2015. A further 62% thought that it is important to have strong trade relationship with China.[189]

Syria

Although Sinophobia is not widely practiced in Syria, the Syrian opposition has accused China for supporting the Government of Bashar al-Assad as China has vetoed UN resolutions condemning Assad's alleged war crimes; Syrian and Lebanese nationalists have burnt Chinese flag in response.[190]

Western world and Latin America

Like China's perception in other countries, China's large population, long history and size has been the subject of fear somewhat. China has figured in the Western imagination in a number of different ways as being a very large civilization existing for many centuries with a very large population; however the rise of the People's Republic of China after the Chinese Civil War has dramatically changed the perception of China from a relatively positive light to negative because of the fear of communism in the West, and reports of human rights abuses from China.

Sinophobia became more common as China was becoming a major source of immigrants for the west (including the American West).[7] Numerous Chinese immigrants to North America were attracted by wages offered by large railway companies in the late 19th century as the companies built the transcontinental railroads.

Sinophobic policies (such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, anti-Chinese zoning laws and restrictive covenants, the policies of Richard Seddon, and the White Australia policy) and pronouncements on the "yellow peril" were in evidence as late as the mid-20th century in the Australia, United States, Canada, and New Zealand.

Czech Republic

In 2016, Czechs and pro-Tibetan activists had defaced Chinese flag ahead of Xi Jinping's visit to the country, showing their strong resentment against China's growing influence and its perceived oppression on Tibetans.[191]

Australia

The Chinese population was active in political and social life in Australia. Community leaders protested against discriminatory legislation and attitudes, and despite the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901, Chinese communities around Australia participated in parades and celebrations of Australia's Federation and the visit of the Duke and Duchess of York.

Although the Chinese communities in Australia were generally peaceful and industrious, resentment flared up against them because of their different customs and traditions. In the mid-19th century, terms such as "dirty, disease ridden, [and] insect-like" were used in Australia and New Zealand to describe the Chinese.[192]

A poll tax was passed in Victoria in 1855 to restrict Chinese immigration. New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia followed suit. Such legislation did not distinguish between naturalised, British citizens, Australian-born and Chinese-born individuals. The tax in Victoria and New South Wales was repealed in the 1860s,

In the 1870s and 1880s, the Growing trade union movement began a series of protests against foreign labour. Their arguments were that Asians and Chinese took jobs away from white men, worked for "substandard" wages, lowered working conditions and refused unionisation.[193] Objections to these arguments came largely from wealthy land owners in rural areas.[193] It was argued that without Asiatics to work in the tropical areas of the Northern Territory and Queensland, the area would have to be abandoned.[194] Despite these objections to restricting immigration, between 1875 and 1888 all Australian colonies enacted legislation which excluded all further Chinese immigration.[194] Asian immigrants already residing in the Australian colonies were not expelled and retained the same rights as their Anglo and Southern compatriots.

In 1888, following protests and strike actions, an inter-colonial conference agreed to reinstate and increase the severity of restrictions on Chinese immigration. This provided the basis for the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act and the seed for the White Australia Policy, which although relaxed over time, was not fully abandoned until the early 1970s.

Number of cases have been reported, related to Sinophobia in the country.[195] Recently, in February 2013, a Chinese football team had reported about the abuses and racism they suffered on Australia Day.[8]

There have been a spate of racist anti-Chinese graffiti and posters in universities across Melbourne and Sydney which host a large number of Chinese students. In July and August 2017, hate-filled posters were plastered around Monash University and University of Melbourne which said, in Mandarin, that Chinese students were not allowed to enter the premises, or else they would face deportation, while a "kill Chinese" graffiti, decorated with swastikas was found at University of Sydney.[196][197] The Antipodean Resistance, a white supremacist group that identifies itself as pro-Nazi, claimed responsibility for the posters on Twitter. The group's website contains anti-Chinese slurs and Nazi imagery.[198]

Anti-Chinese sentiment has witnessed a steady rise in Australia, after China was accused of sending spies and trying to manipulate Australian politics.[199]

France

In France, anti-Chinese sentiment has become an issue, with recent poor treatments of Chinese minority in France like the killing of Chinese people in Paris, causing uproar among Chinese in France;[200] joint alliance with India against China;[201] and land grabs from Chinese investors.[202] A 2018 survey by Institut Montaigne has suggested that Chinese investments in France are viewed more negatively than Chinese tourism to the country, with 50% of respondents holding negative views of the former.[203][204] It was reported in 2017 that there was some negativity among Parisians towards Chinese visitors,[205] but other surveys have suggested that they are not viewed worse than a number of other groups.[206][207][208]

Germany

In 2016, Günther Oettinger, the former European Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society, called Chinese people derogatory names, including "sly dogs," in a speech to executives in Hamburg and had refused to apologize for several days.[209] Two surveys have suggested that a percentage of Germans hold negative views towards Chinese travellers, although it is not as bad as a few other groups.[210][211][212]

Sweden

Sweden was traditionally friendly to China, being the first country to acknowledge the People's Republic of China in the West at 1950 when most of the world deserted from China. Sweden had also helped to assist China during its economic reforms of 1978, and was also the first Western country to allow the operation of Confucius Institute.[213]

However, relations began to deteriorate since 2010s, following the scandal of Chinese tourists disobeying Swedish rule in the country that led to growing tensions.[214] Although the Swedish government doesn't take any single stance, China accused Sweden of maltreatment and the Chinese government unleashed a boycott on Sweden.[215] This event and direct anti-Swedish intention by the Chinese government has led to the growing anti-Chinese sentiment in Sweden to break out, from accusation of China's bullying tactic,[216] the kidnap of China-born Swedish citizen and bookseller Gui Minhai in Thailand,[217] and recently, several Swedish cities have started to cut tie with China's cities amid fear of China's political interference,[218] to the coronavirus outbreak, along with China's concealing of information and disinformation campaign, harassing Uyghurs, which threatens Sweden due to its tradition of respecting freedom and human rights.[219][220]

In May 2020, due to the deterioration of relations, Sweden had decided to shut down all Confucius Institute in the country, stating the Chinese government's meddling in education affairs.[221]

Italy

Although historical relations between two were friendly and even Marco Polo paid a visit to China, during the Boxer Rebellion, Italy was part of Eight-Nation Alliance against the rebellion, thus this had stemmed anti-Chinese sentiment in Italy.[222] Italian troops looted, burnt and stole a lot of Chinese goods to Italy, whom many are still being displayed in Italian museums.[223]

In modern era, Sinophobia still exists in Italy. In 2007, an anti-Chinese unrest occurred when Italian residents of Milan and Rome had complained that, as Chinese neighbourhoods expand, Italian stores are being squeezed out by merchants who obtain licences for retail shops but then open up wholesale distribution operations for goods flooding in from China.[224] In 2010, Italian town of Prato became increasingly anti-Chinese, accusing them for not obeying Italian law.[225]

Spain

Spain first issued anti-Chinese legislation when Limahong, a Chinese pirate, attacked Spanish settlements in the Philippines. One of his famous actions was a failed invasion of Manila in 1574, which he launched with the support of Chinese and Moro pirates.[226] The Spanish conquistadors massacred the Chinese or expelled them from Manila several times, notably the autumn 1603 massacre of Chinese in Manila, and the reasons for this uprising remain unclear. Its motives range from the desire of the Chinese to dominate Manila, to their desire to abort the Spaniards' moves which seemed to lead to their elimination. The Spaniards quelled the rebellion and massacred around 20,000 Chinese. The Chinese responded by fleeing to the Sulu Sultanate and supporting the Moro Muslims in their war against the Spanish. The Chinese supplied the Moros with weapons and joined them in directly fighting against the Spanish during the Spanish–Moro conflict. Spain also upheld a plan to conquer China, but it never materialized.[227]

Peru

Peru was a popular destination for Chinese immigrants at 19th century, mainly due to its vulnerability over slave market and subsequent needed for Peru over military and laborer workforce. However, relations between Chinese workers and Peruvian owners have been tense, due to mistreatments over Chinese laborers and anti-Chinese discrimination in Peru.[14]

Due to the Chinese support for Chile throughout the War of the Pacific, relations between Peruvians and Chinese became increasingly tenser in the aftermath. After the war, armed indigenous peasants sacked and occupied haciendas of landed elite criollo "collaborationists" in the central Sierra – majority of them were of ethnic Chinese, while indigenous and mestizo Peruvians murdered Chinese shopkeepers in Lima; in response to Chinese coolies revolted and even joined the Chilean Army.[228][229] Even in 20th century, memory of Chinese support for Chile was so deep that Manuel A. Odría, once dictator of Peru, issued a ban against Chinese immigration as a punishment for their betrayal.[230] This caused a deep wound still relevant today in Peru.

Canada

In the 1850s, sizable numbers of Chinese immigrants came to British Columbia seeking gold; the region was known to them as Gold Mountain. Starting in 1858, Chinese "coolies" were brought to Canada to work in the mines and on the Canadian Pacific Railway. However, they were denied by law the rights of citizenship, including the right to vote, and in the 1880s, "head taxes" were implemented to curtail immigration from China. In 1907, a riot in Vancouver targeted Chinese and Japanese-owned businesses. In 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, commonly known as the Exclusion Act, prohibiting further Chinese immigration except under "special circumstances". The Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947, the same year in which Chinese Canadians were given the right to vote. Restrictions would continue to exist on immigration from Asia until 1967, when all racial restrictions on immigration to Canada were repealed, and Canada adopted the current points based immigration system. On June 22, 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology and compensation only for the head tax once paid by Chinese immigrants.[231] Survivors or their spouses were paid approximately CAD$20,000 in compensation.[232]

Sinophobia in Canada has been fueled by allegations of extreme real estate price distortion resulting from Chinese demand, purportedly forcing locals out of the market.[233]

Brazil

There is Sinophobic sentiment in Brazil, largely due to the issue over economic and political manipulation from China over Brazil. Recently, Chinese have been accused for grabbing land in Brazil, involving on unclean political ties, further deepens Sinophobia in Brazil.[234] Chinese investments in Brazil have been largely influenced by this negative impression.[235]

Current Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has shown distrust towards China during his presidential campaign, saying claiming they "[want to] buy Brazil."[236][237]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom developed a strong Sinophobic sentiment dated back at 1800s when China and the British Empire fought for influence in Asia. It resulted with the First Opium War which Qing China suffered a tremendous defeat and was forced to pay a fee.[238] Since then, due to strong anti-British sentiment in China, anti-Chinese sentiment grew in the U.K. as a response.

Today, negative impression over China continues to be an issue in the United Kingdom. The Chinese emigrants in Britain often issued themselves to be among the most discriminated people,[239] and there is a lack of reporting over anti-Chinese discrimination in the U.K. as consequence, notably violence against Chinese Britons.[240] Further, British Chinese even claimed they had been "ignored" from such discrimination.[241]

Portugal

In the 16th century, increasing sea trades between Europe to China had led Portuguese merchants to China, however Portuguese military ambitions for power and its fear of China's interventions and brutality had led to the growth of Sinophobia in Portugal. Galiote Pereira, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary who was imprisoned by Chinese authorities, claimed China's juridical treatment known as bastinado was so horrible as it hit on human flesh, becoming the source of fundamental anti-Chinese sentiment later; as well as brutality, cruelty of China and Chinese tyranny.[242] With Ming China's brutal reactions on Portuguese merchants following the conquest of Malacca,[243] Sinophobia became widespread in Portugal, and widely practiced until the First Opium War, which Qing China was forced to cede Macau for Portugal.[244]

Mexico

Anti-Chinese sentiment was first recorded in Mexico at 1880s. Similar to most Western countries at the time, Chinese immigration and its large business involvement has always been a fear for native Mexicans. Violence against Chinese occurred such as in Sonora, Baja California and Coahuila, the most notable was the Torreón massacre,[245] although it was sometimes argued to be different than other Western nations.[246]

New Zealand

Anti-Chinese sentiment grew in New Zealand at 19th century when the British Empire issued the Yellow Perils to embrace xenophobic sentiment against Chinese population and China, and it remains relevant today in New Zealand. It was begun with Chinese Immigration Acts at 1881, limiting Chinese from emigrating to New Zealand and excluding Chinese from major jobs, to even anti-Chinese organizations.[247] Today, mostly anti-Chinese sentiment in New Zealand is about the labor issue.[247]

K. Emma Ng reported that "One in two New Zealanders feel the recent arrival of Asian migrants is changing the country in undesirable ways"[247]

Attitudes on Chinese in New Zealand is suggested to have remained fairly negative, with some Chinese still considered to be less respected people in the country.[248]

United States

Starting with the California Gold Rush in the late 19th century, the United States—particularly the West Coast states—imported large numbers of Chinese migrant laborers. Employers believed that the Chinese were "reliable" workers who would continue working, without complaint, even under destitute conditions.[249] The migrant workers encountered considerable prejudice in the United States, especially among the people who occupied the lower layers of white society, because Chinese "coolies" were used as a scapegoat for depressed wage levels by politicians and labor leaders.[250] Cases of physical assaults on the Chinese include the Chinese massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles and the murder of Vincent Chin on June 23, 1982. The 1909 murder of Elsie Sigel in New York, for which a Chinese person was suspected, was blamed on the Chinese in general and it immediately led to physical violence against them. "The murder of Elsie Sigel immediately grabbed the front pages of newspapers, which portrayed Chinese men as dangerous to "innocent" and "virtuous" young white women. This murder led to a surge in the harassment of Chinese in communities across the United States."[251]

The emerging American trade unions, under such leaders as Samuel Gompers, also took an outspoken anti-Chinese position,[252] regarding Chinese laborers as competitors to white laborers. Only with the emergence of the international trade union, IWW, did trade unionists start to accept Chinese workers as part of the American working-class.[253]

In the 1870s and 1880s various legal discriminatory measures were taken against the Chinese. These laws, in particular the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were aimed at restricting further immigration from China.[13] although the laws were later repealed by the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943. In particular, even in his lone dissent against Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), then-Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote of the Chinese as: "a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race."[254]

In the 2010 United States elections, a significant number[255] of negative advertisements from both major political parties focused on a candidates' alleged support for free trade with China which were criticized by Jeff Yang for promoting anti-Chinese xenophobia.[256] Some of the stock images that accompanied ominous voiceovers about China were actually of Chinatown, San Francisco.[256] These advertisements included one produced by Citizens Against Government Waste called "Chinese Professor," which portrayed a 2030 conquest of the West by China and an ad by Congressman Zack Space attacking his opponent for supporting free trade agreements like NAFTA, which the ad had claimed caused jobs to be outsourced to China.[257]

In October 2013, a child actor on Jimmy Kimmel Live! jokingly suggested in a skit that the U.S. could solve its debt problems by "kill[ing] everyone in China."[258][259]

Donald Trump, the 45th President of the United States, was accused of promoting Sinophobia throughout his campaign for the Presidency in 2016.[260][261] and it was followed by his imposition of trade tariffs on Chinese goods, which was seen as a declaration of a trade war and another anti-Chinese act.[262] The deterioration of relations has led to a spike in anti-Chinese sentiment in the US.[263][264] According to a Pew Research Center poll released in August 2019, 60 percent of Americans had negative opinions about China, with only 26 percent holding positive views. The same poll found that the country was named as America's greatest enemy by 24 percent of respondents in USA, tied along with Russia.[265] He has also referred to the COVID 19 virus as the "chinese virus" and "kung-flu"

It has been noted that there is a negative bias in American reporting on China.[266][267][268] And many Americans, including American-born Chinese, have continuously held prejudices toward mainland Chinese people[269][270][271] which include perceived rudeness and unwillingness to stand in line,[272][273] even though there are sources that have reported contrary to those stereotypes.[274][275][276][277][278][279] A survey in 2019 though has suggested that some Americans still hold positive views of Chinese visitors to the US.[280]

Venezuela

A recent increasing Sinophobic sentiment sparked in Venezuela in the 2010s as for the direct consequence of Venezuelan crisis, which China was accused for looting and exploiting Venezuelan natural resources and economic starvation in the country, as well as its alliance to the current Venezuelan government of Nicolás Maduro.[281]

Africa

Anti-Chinese populism has been an emerging presence in some African countries.[282] There have been reported incidents of Chinese workers and business-owners being attacked by locals in some parts of the continent.[283][284] Recent reports of evictions, discrimination and other mistreatment of Africans in Guangzhou during the COVID-19 pandemic[285] has led to expressed animosity from some African politicians towards Chinese ambassadors.[286]

Kenya

Anti-Chinese sentiment broke out in Kenya when Kenyans accused Chinese for looting and stealing jobs from Kenyans, thus attacking Chinese workers and Chinese immigrants inside the country in 2016.[287]

Ghana

Ghanaians have alleged Chinese miners of illegally seizing jobs, polluting community water supplies, and disturbing agricultural production through their work.

A sixteen-year-old illegal Chinese miner was shot in 2012, while trying to escape arrest.[288]

Zambia

In 2006, Chinese businesses were targeted in riots by angry crowds after the electoral defeat of the anti-China Patriotic Front.[289] In 2018, a reported spate of violent incidents targeting the Chinese community was allegedly linked to local politics.[290] Presidential candidate Michael Sata frequently invoked anti-Chinese rhetoric prior to winning his election in 2011,[291] once describing the Chinese in Zambia as not investors but "invaders". A 2016 study from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology suggested though that locals held more nuanced views of Chinese people, ranking them not as highly as Caucasians, but also less negatively than Lebanese, and to some extent, Indian people.[292]

South Africa

During the 19th century the British Empire, which used to control most of South Africa, spread Sinophobia across the country.

Recent rise of Sinophobic sentiment in South Africa is largely contributed to by economic looting from China and growing Chinese influence in the country. In 2015, South Africa planned to allow for Mandarin to be taught in schools in South Africa solicited umbrage from the teachers' union and set social media and comment sections ablaze with fears of a Chinese "imperialism" in Africa and a new "colonialism"; as well as recent increasing Chinese immigration to the country.[293] A hate speech case was brought to light in 2017 for the Facebook comments found on a Carte Blanche animal abuse video, with 12 suspects on trial.[294]

In 2017, violence against Chinese immigrants and other foreign workers broke out in Durban, then quickly spread out in other major cities in South Africa as for the result of Chinese fears over taking South Africa.[295] Xenophobia towards the Chinese has sometimes manifested in the form of robberies or hijackings,[296]

Depiction of China and Chinese in media

Depiction of China and Chinese in official media have been somewhat under subject in general, but overall, the majority of depiction over China and Chinese are surrounded about coverages, mainly, as negative. In 2016, Hong Kong's L. K. Cheah said to South China Morning Post that Western journalists who regard China's motives with suspicion and cynicism are cherry-picking facts based on a biased view, and the misinformation they produce as a result is unhelpful, and sympathetic of the resentment against China.[297] Many Chinese consider this is "war of information".

According from China Daily, a nationalist press of China, Hollywood is accused for its negative portrayal of Chinese in movies, such as bandits, dangerous, cold-blood, weak and cruel;[298] while the Americans as well as several European or Asians like Filipino, Taiwanese, Korean, Hong Konger, Vietnamese, Indian and Japanese characters in general are depicted as saviors, even anti-Chinese whitewashing in film is common. Matt Damon, the American actor who appeared in The Great Wall, had also faced criticism that he had participated in "whitewashing" through his involvement in forthcoming historical epic The Great Wall, a large-scale Hollywood-Chinese co-production, which he denied.[299] Several another examples is the depiction of ancient Tang Chinese in Yeon Gaesomun, a Korean historical drama, as "barbaric, inhuman, violent" seeking to conquer Goguryeo and subjecting Koreans.[300][301][302]

In practice, anti-Chinese political rhetoric usually puts emphasis on highlighting policies and alleged practices of the Chinese government that are criticised internally - corruption, human rights issues, unfair trades, censorship, violence, military expansionism, political interferences and historical imperialist legacies. It is often in line with independent media opposing Chinese Government in Mainland China as well as in the Special Administrative Regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau.[303] In defence of this rhetoric, some sources critical of the Chinese government claim that it is Chinese state-owned media and administration who attempt to discredit the "neutral" criticism by generalizing it into indiscriminate accusations of the whole Chinese population and targeting those who criticize the regime[304] - or Sinophobia.[303][305][306][307] Some have argued, however, that the Western media, similar to Russia's case, doesn't make enough distinction between CPC's regime and China and the Chinese, thus effectively vilifying the whole nation.[308]

Business

Due to the deep resentment over China-made business as well as alleged unfair trades from Chinese corporations, several countries have taken measures to ban or limit Chinese companies from investing in its markets. Notably is the case of Huawei and ZTE, which were banned from operating or doing business with American companies in the United States due to alleged involvements from Chinese Government and security concerns.[309][310][311] It was seen as discrimination against China. Some countries like India also moves closer to full ban or limit operations of Chinese corporations inside their countries for the exact reasons.[312][313]

According to The Economist, many Western as well as non-Chinese investors still think that anything to do with China is somewhat "dirty" and unfresh[314] as most look on China as a country which often interferes on other businesses. Alexandra Stevenson from The New York Times also noted that "China wants its giant national companies to be world leaders in sectors like electric cars, robotics and drones, but the authorities are accused of curtailing foreign firms' access to Chinese consumers."[315]

Historical Sinophobia-led violence

List of non-Chinese "sinophobia-led" violence against ethnic Chinese

Australia

- Lambing Flat riots

- Buckland Riot

Mexico

Dutch East Indies

Malaysia

- 13 May incident (Malaysia)

By the Japanese during World War 2

.jpg)

- Nanking Massacre

- Sook Ching massacre

- Changkiao massacre

By Koreans

- Wanpaoshan Incident, on July 1, 1931

United States

Vietnam

- 2014 Vietnam anti-China protest

Derogatory terms

There are a variety of derogatory terms referring to China and Chinese people. Many of these terms are viewed as racist. However, these terms do not necessarily refer to the Chinese ethnicity as a whole; they can also refer to specific policies, or specific time periods in history.

In English

- Eh Tiong – refers specifically to Chinese nationals. Primarily used in Singapore to differentiate between the Singaporeans of Chinese heritage and Chinese nationals. From the Hokkien '阿中', 中 an abbreviation for China. Considered offensive.

- Cheena – same usage as 'Eh Tiong' in Singapore.

- Chinaman – the term Chinaman is noted as offensive by modern dictionaries, dictionaries of slurs and euphemisms, and guidelines for racial harassment.

- Ching chong – Used to mock people of Chinese descent and the Chinese language, or other East Asian looking people in general.

- Ching chang chong – same usage as 'ching chong'.

- Chink – racial slur referring to a person of Chinese ethnicity, but could be directed towards anyone of East Asian descent in general.

- Chinky – the name "chinky" is the adjectival form of chink and, like chink, is an ethnic slur for Chinese occasionally directed towards other East Asian people.

- Chonky – refers to a person of Chinese heritage with white attributes whether being a personality aspect or physical aspect.[316][317]

- Corona - recently used in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, in assumptions that everyone of Chinese descent contracts the virus.

- Coolie – means Laborer in reference to Chinese manual workers in the 19th and early 20th century.

- Slope – used to mock people of Chinese descent and the sloping shape of their skull, or other East Asians. Used commonly during the Vietnam War.

- Chicom – used to refer to a Communist Chinese.

- Panface – used to mock the flat facial features of the Chinese and other people of East and Southeast Asian descent. Used commonly during the era of British Colonisation of East Asia.

- Lingling – used to call someone of Chinese descent.

- Chinazi – a recent anti-Chinese abusive sentiment which compares China to Nazi Germany, combining the word "China" and "Nazi". First published by Chinese dissident Yu Jie,[318][319] it becomes frequently used during Hong Kong protests against the Beijing government.[320][321]

- Made in China – used to mock a purported low quality product, which can extend to other pejoratively perceived aspects of the country.[102]

- Wuflu/Kung Flu – emerged in the United States in reference to COVID-19 during the COVID-19 pandemic. These terms are linked to Wuhan, where the virus was first detected, or China in general, via portmanteau with terms from traditional Chinese Martial Arts, Wushu and Kung Fu.[322][323]

In Filipino (Tagalog)

- Intsik – is used to refer to refer people of Chinese ancestry including Chinese Filipinos. The originally neutral term recently gained negative connotation with the increasing preference of Chinese Filipinos not to be referred to as intsik. The term originally came from in chiek, a Hokkien term referring to one's uncle. The term has variations, which may be more offensive in tone such as intsik beho and may used in a deregatory phrase, intsik beho tulo laway ("old Chinaman with drooling saliva").[324][325]

- Tsekwa (sometimes spelled chekwa) – is a slang term used by the Filipinos to refer Chinese people.[326]

In French

- Chinetoque (m/f) – derogatory term referring to Asian people.

In Indonesian

- Cokin, derogatory term to Asian people[327]

- Panlok (Panda lokal/local panda): derogatory term referring to Chinese female or female who look like Chinese, particularly prostitute[328]

In Japanese

- Dojin (土人, dojin) – literally "earth people", referring either neutrally to local folk or derogatorily to indigenous peoples and savages, used towards the end of the 19th century and early 20th century by Japanese colonials, being a sarcastic remark regarding backwardsness.

- Tokuajin (特亜人, tokuajin) – literally "particular Asian people", derogatory term used against Koreans and Chinese.

- Shina (支那 (シナ), shina) – Japanese reading of the Chinese character compound "支那" (Zhina in Mandarin Chinese), originally a Chinese transcription of an Indic name for China that entered East Asia with the spread of Buddhism. Its effect when a Japanese person uses it to refer to a Chinese person is considered by some people to be similar to the American connotation of the word "negro", a word that has harmless etymologies but has gained derogative connotations due to historical context, where the phrase shinajin (支那人, lit. "Shina person") was used refer to Chinese. The slur is also extended towards left-wing activists by right-wing people.[329]

- Chankoro (チャンコロ, chankoro) – derogatory term originating from a corruption of the Taiwanese Hokkien pronunciation of 清国奴 Chheng-kok-lô͘, used to refer to any "chinaman", with a meaning of "Qing dynasty's slave".

In Korean

- Jjangkkae (Korean: 짱깨) – the Korean pronunciation of 掌櫃 (zhǎngguì), literally "shopkeeper", originally referring to owners of Chinese restaurants and stores;[330] derogatory term referring to Chinese people.

- Seom jjangkkae (Korean: 섬짱깨) – literally "island shopkeeper"; referring to Taiwanese people.

- Jjangkkolla (Korean: 짱꼴라) – this term has originated from Japanese term chankoro (淸國奴, lit. "slave of Qing Manchurian"). Later, it became a derogatory term that indicates people in China.[331]

- Jung-gong (Korean: 중공; Hanja: 中共) – literally "Chinese communist", it is generally used to refer to Chinese communists and nationalists, since the Korean War (1950–1953).

- Orangkae (Korean: 오랑캐) – literally "Barbarian", derogatory term used against Chinese, Mongolian and Manchus.

- Dwoenom (Korean: 되놈) – It originally was a demeaning word for Jurchen meaning like 'barbarians' because Koreans looked down and treat Jurchen as inferior. But Jurchen (1636) invaded Korea (Joseon) and caused longterm hatred. Then Jurchen would take over China and make the Qing Dynasty. Koreans completely changed the view of China that China has now become taken over by hateful Dwoenom 'barbarians', so Koreans now called all of China as 'Dwoenom' not just Jurchen/Manchu.[332]

- Ttaenom (Korean: 때놈) – literally "dirt bastard", referring to the perceived "dirtiness" of Chinese people, who some believe do not wash themselves. It was originally Dwoenom but changed over time to Ddaenom.

In Mongolian

- Hujaa (Mongolian: хужаа) – derogatory term referring to Chinese people.

- Jungaa – a derogatory term for Chinese people referring to the Chinese language.

In Portuguese

In Russian

In Spanish

- Chino cochino – (coe-chee-noe, N.A. "cochini", SPAN "cochino", literally meaning "pig") is an outdated derogatory term meaning dirty Chinese. Cochina is the feminine form of the word.

In Italian

- Muso giallo – literally "yellow muzzle". It is an offensive term used to refer to Chinese people, sometimes to Asian in general, with intent to point out their yellowish complexion as an indication of racial inferiority. The use of the word "muzzle" is in order not to consider them humans, but animals.

In Vietnamese

- Tàu – literally "boat". It is used to refer to Chinese people in general, can be construed as derogatory. This usage is derived from the fact that many Chinese refugees came to Vietnam in boats during the Qing dynasty.

- Khựa – neologism, derogatory term for Chinese people and combination of two words above is called Tàu Khựa, that is a common word

- Tung Của or Trung Của or Trung Cẩu (lit. Dog Chinese) – the parody spelling of the word "中国" (China) which spells as "zhong guó" in a scornful way, but rarely used.

- Trung Cộng or Tàu Cộng (Chinese communists or Communist China) – used by Vietnamese anti-communists, mostly in exile, as a mockery toward China's political system and its imperialist desires.[335][336][337]

In Cantonese

In Taiwanese

- Si-a-liok (Written in traditional Chinese: 死阿陸; Taiwanese Romanization: Sí-a-lio̍k or Sí-a-la̍k) – literally "damn mainland Chinese", sometimes uses "四二六" (426, "sì-èr-liù") in Mandarin as word play. See also: 阿陸仔.

In Burmese

- Taruk (တရုပ်) – literally mean "Turks". It is used as derogatory term about Chinese people in general. First issued during the First Mongol invasion of Burma, the Chinese are widely seen as barbarian hordes from the north. That reflected the geographical and political dimensions at the time, when the Mongols ruled mainland China and the Turks formed the largest of Mongol Army. Now rarely used due to warm Sino-Burmese relations.

Chinese response