Fu Manchu

Dr. Fu Manchu is a fictional villain who was introduced in a series of novels by the English author Sax Rohmer during the first half of the 20th century. The character was also extensively featured in cinema, television, radio, comic strips and comic books for over 90 years and he has also become an archetype of the evil criminal genius and mad scientist, while lending the name to the Fu Manchu mustache.

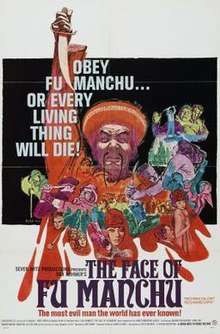

| Dr. Fu Manchu | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Mitchell Hooks for 1965 film The Face of Fu Manchu | |

| First appearance | The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu |

| Last appearance | Emperor Fu Manchu |

| Created by | Sax Rohmer |

| Portrayed by |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Mad scientist, supervillain, anti-hero |

| Nationality | Chinese Manchu |

Background

According to his own account, Sax Rohmer decided to start the Dr. Fu Manchu series after his Ouija board spelled out C-H-I-N-A-M-A-N when he asked what would make his fortune.[1] During this time period, the notion of the "Yellow Peril" was spreading in North American society.

Rohmer wrote 14 novels concerning the villain.[2] The image of Orientals invading Western nations became the foundation of Rohmer's commercial success, being able to sell 20 million copies in his lifetime.[3]

Characters

Dr. Fu Manchu

—The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu

Supervillain Dr. Fu Manchu's murderous plots are marked by the extensive use of arcane methods; he disdains guns or explosives, preferring dacoits, Thugs, and members of other secret societies as his agents (usually armed with knives), or using "pythons and cobras ... fungi and my tiny allies, the bacilli ... my black spiders" and other peculiar animals or natural chemical weapons. He has a great respect for the truth (in fact, his word is his bond), and uses torture and other gruesome tactics to dispose of his enemies.[4]

Dr. Fu Manchu is described as a mysterious villain because he seldom appears on the scene. He always sends his minions to commit crimes for him. In the novel The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu, he sends a beautiful young girl to the crime scene to see the victim is dead. He also sends a dacoit to attack Sir Denis Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie.

In the novel Fu Manchu's Bride (1933), Dr. Fu Manchu claims to hold doctorates from four Western universities, while in Emperor Fu Manchu (1959), he states that he attended Heidelberg University, the Sorbonne, and the University of Edinburgh (in the film The Mask of Fu Manchu, however, he states proudly that "I am a doctor of philosophy from Edinburgh, a doctor of law from Christ's College, a doctor of medicine from Harvard. My friends, out of courtesy, call me 'Doctor' ".). At the time of their first encounter (1911), Dr. Petrie believed that Dr. Fu Manchu was more than 70 years old. This would mean he was studying for his first doctorate in the 1860s or 1870s.

According to Cay Van Ash, Rohmer's biographer and former assistant who became the first author to continue the series after Rohmer's death, "Fu Manchu" was a title of honor, which meant "the warlike Manchu". Van Ash speculates that Dr. Fu Manchu had been a member of the imperial family of China, who had backed the losing side in the Boxer Rebellion. In the early books (1913–1917), Dr. Fu Manchu is an agent of the Chinese tong known as the Si-Fan and acts as the mastermind behind a wave of assassinations targeting Western imperialists. In the later books (1931–1959), he has gained control of the Si-Fan, which has been changed from a mere Chinese tong into an international criminal organization under his leadership which, in addition to attempting to take over the world and restore China to its ancient glory (Dr. Fu Manchu's main goals right from the beginning), also tries to rout fascist dictators and then halt the spread of worldwide Communism both for its leader's own selfish reasons, Dr. Fu Manchu knowing them both to be major rivals in his plans for world domination. The Si-Fan is largely funded through criminal activities, particularly the drug trade and human trafficking (or "white slavery"). Dr. Fu Manchu has extended his already considerable lifespan by use of the elixir of life, a formula that he had spent decades trying to perfect.

Sir Denis Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie

Opposing Dr. Fu Manchu in the stories are Sir Denis Nayland Smith and, in the first three books, Dr. Petrie. They are in the Holmes and Watson tradition, with Petrie narrating the stories (after the third book, they would be narrated by various others allied with Smith right up to the end of the series) while Smith carries the fight, combating Dr. Fu Manchu more by sheer luck and dogged determination than intellectual brilliance (except in extremis). Smith and Dr. Fu Manchu share a grudging respect for one another, as each believes that a man must keep his word, even to an enemy.

In the first three books, Smith is a colonial police commissioner in Burma granted a roving commission, which allows him to exercise authority over any group that can help him in his mission. He resembles Sherlock Holmes in physical description and acerbic manner, but not in deductive genius. He has been criticized as being a racist and jingoistic character, especially in the early books in the series, and gives voice to anti-Asian sentiments. When Rohmer revived the series in 1931, Smith (who has been knighted by this time for his efforts to defeat Dr. Fu Manchu, although he would always admit that the honor was not earned by superior intellect) is an ex-Assistant Commissioner of Scotland Yard. He later accepts a position with the British Secret Service. Several books have him placed on special assignment with the FBI.

Actors who played Dr. Fu Manchu:

- Harry Agar Lyons in The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1923) and The Further Mysteries of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1924)

- Warner Oland in The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929), The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930), Paramount on Parade (1930), and Daughter of the Dragon (1931)

- Boris Karloff in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932)

- Lou Marcelle in The Shadow of Fu Manchu (1939–1940)

- Henry Brandon in Drums of Fu Manchu (1940)

- John Carradine in Fu Manchu: The Zayat Kiss (1952)

- Glen Gordon in The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu (1956)

- Christopher Lee in The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966), The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967), The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968), and The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969)

- Peter Sellers in The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980)

- Nicolas Cage in Grindhouse (2007)

Actors who played Sir Denis Nayland Smith:

- Fred Paul in The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1923) and The Further Mysteries of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1924)

- O.P. Heggie in The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929) and The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930)

- Lewis Stone in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932)

- Hanley Stafford in The Shadow of Fu Manchu (1939–1940)

- William Royle in Drums of Fu Manchu (1940)

- Cedric Hardwicke in Fu Manchu: The Zayat Kiss (1952)

- Lester Matthews in The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu (1956)

- Nigel Green in The Face of Fu Manchu (1965)

- Douglas Wilmer in The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966) and The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967)

- Richard Greene in The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968) and The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969)

- Peter Sellers in The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980)

Actors who played Dr. Petrie:

- H. Humberston Wright in The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1923) and The Further Mysteries of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1924)

- Neil Hamilton in The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929) and The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930)

- Holmes Herbert in Daughter of the Dragon (1931)

- Gale Gordon in The Shadow of Fu Manchu (1939–1940)

- Olaf Hytten in Drums of Fu Manchu (1940)

- John Newland in Fu Manchu: The Zayat Kiss (1952)

- Clark Howat in The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu (1956)

- Howard Marion-Crawford in The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966), The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967), The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968) and The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969)

Kâramanèh

—The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu

Prominent among Dr. Fu Manchu's agents was the "seductively lovely" Kâramanèh. Her real name is unknown. She was sold to the Si-Fan by Egyptian slave traders while she was still a child. Karamaneh falls in love with the narrator of the first three books in the series, Dr. Petrie. She rescues Petrie and Nayland Smith many times. Eventually, the couple are united and she wins her freedom. They marry and have a daughter, Fleurette, who figures in two later novels (Fu Manchu's Bride (1933) and its sequel, The Trail of Fu Manchu (1934)). Author Lin Carter later created a son for Dr. Petrie and Karamaneh, but this character is not considered canonical.

Fah Lo Suee

Dr. Fu Manchu's daughter, Fah Lo Suee, is a devious mastermind in her own right, frequently plotting to usurp her father's position in the Si-Fan and aiding his enemies both within, and outside of, the organization. Her real name is unknown; Fah Lo Suee was a childhood term of endearment. She was introduced anonymously while still a teenager in the third book in the series and plays a larger role in several of the titles of the 1930s and 1940s. She was known for a time as Koreani after being brainwashed by her father, but her memory was later restored. She is infamous for taking on false identities like her father, among them Madame Ingomar, Queen Mamaloi and Mrs. van Roorden. In film, she has been portrayed by numerous actresses over the years. Her character is usually renamed in film adaptations because of difficulties with the pronunciation of her name. Anna May Wong played Ling Moy in 1931's Daughter of the Dragon. Myrna Loy portrayed the similarly-named Fah Lo See in 1932's The Mask of Fu Manchu. Gloria Franklin had the role of Fah Lo Suee in 1940's Drums of Fu Manchu. Laurette Luez played Karamaneh in 1956's The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu, but the character owed more to Fah Lo Suee than Rohmer's depiction of Karamaneh. Tsai Chin portrayed Dr. Fu Manchu's daughter, Lin Tang, in the five Christopher Lee films of the 1960s.

Controversy

As an ethnic fictional criminal mastermind, Dr. Fu Manchu has sparked numerous controversies of racism and "Orientalism", from his fiendish design to his faux Chinese name.[5] After the release of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's film adaptation of The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), which featured the Chinese villain telling an assembled group of "Asians" (consisting of caricatured Indians, Persians and Arabs) that they must "kill the white man and take his women", the Chinese embassy in Washington, D.C. issued a formal complaint against the film.[6]

Following the release of Republic Pictures' serial adaptation of Drums of Fu Manchu (1940), the United States Department of State requested the studio make no further films about the character, as China was an ally against Japan during World War II. Likewise, Rohmer's publisher, Doubleday, refused to publish further additions to the best-selling series for the duration of World War II once the United States entered the conflict. BBC Radio and Broadway investors subsequently rejected Rohmer's proposals for an original Fu Manchu radio serial and stage show during the 1940s.

The re-release of The Mask of Fu Manchu in 1972 was met with protest from the Japanese American Citizens League, who stated that "the movie was offensive and demeaning to Asian Americans".[7] Due to this protest, CBS television decided to cancel a showing of The Vengeance of Fu Manchu. Los Angeles TV station KTLA shared similar sentiments, but ultimately decided to run The Brides of Fu Manchu with the disclaimer: "This feature is presented as fictional entertainment and is not intended to reflect adversely on any race, creed or national origin."[8]

Rohmer responded to charges that his work demonized Asians in Master of Villainy, a biography co-written by his wife:

Of course, not the whole Chinese population of Limehouse was criminal. But it contained a large number of persons who had left their own country for the most urgent of reasons. These people knew no way of making a living other than the criminal activities that had made China too hot for them. They brought their crimes with them.

It was Rohmer's contention that he based Dr. Fu Manchu and other "Yellow Peril" mysteries on real Chinese crime figures he met as a newspaper reporter covering Limehouse activities.

In May 2013, General Motors cancelled an advertisement after complaints that a phrase it contained, "the land of Fu Manchu", which was intended to refer to China, was offensive.[9]

Characterizing Dr. Fu Manchu as an overtly racist creation has been criticized in the book Lord of Strange Deaths: The Fiendish World of Sax Rohmer.[10] In a review of the book in The Independent, Dr. Fu Manchu is contextualized: "These magnificently absurd books, glowing with a crazed exoticism, are really far less polar, less black-and-white, less white-and-yellow, than they first seem."[11]

Cultural impact

The style of facial hair associated with him in film adaptations has become known as the Fu Manchu mustache. The "Fu Manchu" mustache is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as a "long, narrow moustache whose ends taper and droop down to the chin",[12] although Rohmer's writings described the character as wearing no such adornment.

Before the creation of Dr. Fu Manchu, Chinese people in Western culture were usually portrayed as victims in Western dominance. Dr. Fu Manchu was a new phase in Western culture where, suddenly, Chinese people were portrayed as the perpetrators and a threat to Western culture.[13]

Because of this, the character of Dr. Fu Manchu became, for some, a stereotype embodying the "yellow peril".[3] For some others, Dr. Fu Manchu became the most notorious personification of Western views towards the Chinese,[13] and became the model for other villains in contemporary "yellow peril" thrillers: these villains often had characteristics consistent with the xenophobic ideologies towards East Asian people during the period of Western colonialism.[14]

After World War II, the stereotype inspired by Dr. Fu Manchu increasingly became a subject of satire. Fred Fu Manchu, a "famous Chinese bamboo saxophonist", was a recurring character on The Goon Show, a 1950s British radio comedy program. He was featured in the episode "The Terrible Revenge of Fred Fu Manchu" in 1955 (announced as "Fred Fu Manchu and his Bamboo Saxophone"), and made minor appearances in other episodes (including "China Story", "The Siege of Fort Night", and in "The Lost Emperor" as "Doctor Fred Fu Manchu, Oriental tattooist"). The character was created and performed by Spike Milligan, who used it to mock British xenophobia and self-satisfaction, the traits that summoned the original Fu Manchu into existence, and not as a slur against Asians.[15] The character was further parodied in a later radio comedy, Round the Horne, as Dr Chu En Ginsberg MA (failed), portrayed by Kenneth Williams.

In 1977, Trebor produced a "Fu Munchews" sweet.[16]

Dr. Fu Manchu was parodied in the character of the Fiendish Dr. Wu in the action-comedy film Black Dynamite (2009), in which the executor of an evil plan against African-Americans is an insidious, mustache-sporting kung fu master.[17]

Books

- The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu (1913) (U.K. title: The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu).

- The Return of Dr Fu-Manchu (1916) (U.K. title: The Devil Doctor)

- The Hand of Fu-Manchu (1917) (U.K. title: The Si-Fan Mysteries)

- Daughter of Fu Manchu (1931)

- The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932)

- Fu Manchu's Bride (1933) (U.K. title: The Bride of Fu Manchu)

- The Trail of Fu Manchu (1934)

- President Fu Manchu (1936)

- The Drums of Fu Manchu (1939)

- The Island of Fu Manchu (1941)

- Shadow of Fu Manchu (1948)

- Re-Enter Fu Manchu (1957) (U.K. title: Re-Enter Dr. Fu Manchu)

- Emperor Fu Manchu (1959) This was Rohmer's last novel, published before his death.

- The Wrath of Fu Manchu (1973) was a posthumous anthology containing the title novella, first published in 1952, and three later short stories: "The Eyes of Fu Manchu" (1957), "The Word of Fu Manchu" (1958), and "The Mind of Fu Manchu" (1959).

- Ten Years Beyond Baker Street (1984). The first of two authorized continuation novels by Cay Van Ash, Sax Rohmer's former assistant and biographer. Set in early 1914, it sees Dr. Fu Manchu come into conflict with Sherlock Holmes.

- The Fires of Fu Manchu (1987). The second authorized continuation novel by Cay Van Ash. The novel is set in 1917 and documents Smith and Petrie's encounter with Dr. Fu Manchu during the First World War, culminating in Smith's knighthood. A third Van Ash continuation title, The Seal of Fu Manchu, was underway when Van Ash died in 1994. The incomplete manuscript is believed to be lost.

- The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009). The first of three authorized continuation novels by William Patrick Maynard. The novel expands on the continuity established in Van Ash's books and sees Dr. Petrie teaming with both Nayland Smith and a Rohmer character from outside the series, Gaston Max, in an adventure set on the eve of the First World War.

- The Destiny of Fu Manchu (2012). The second authorized continuation novel by William Patrick Maynard. The novel is set between Rohmer's The Drums of Fu Manchu and The Island of Fu Manchu on the eve of the Second World War and follows the continuity established in the author's first novel.

- The Triumph of Fu Manchu (announced). The third authorized continuation novel by William Patrick Maynard. The novel is set between Rohmer's The Trail of Fu Manchu and President Fu Manchu.

- The League of Dragons by George Alec Effinger was an unpublished and unauthorized novel involving a young Sherlock Holmes matching wits with Dr. Fu Manchu in the 19th century. Two chapters have been published in the anthologies Sherlock Holmes in Orbit (1995) and My Sherlock Holmes (2003). This lost University adventure of Holmes is narrated by Conan Doyle's character Reginald Musgrave.

Dr. Fu Manchu also made appearances in the following non-Fu Manchu books:

- "Sex Slaves of the Dragon Tong" and "Part of the Game" are a pair of related short stories by F. Paul Wilson appearing in his collection Aftershocks and Others: 19 Oddities (2009) and feature anonymous appearances by Dr. Fu Manchu and characters from Little Orphan Annie.

- Dr. Fu Manchu appears under the name "the Doctor" in several stories in August Derleth's Solar Pons detective series. Derleth's successor, Basil Copper, also made use of the character.

- Dr. Fu Manchu is the name of the Chinese ambassador in Kurt Vonnegut's Slapstick (1976).

- It is revealed that Chiun, the Master of Sinanju has worked for the Devil Doctor, as have previous generations of Masters, in The Destroyer #83, Skull Duggery.

- Dr. Fu Manchu also appears in the background to Ben Aaronovitch's Rivers of London series. In this depiction, Dr. Fu Manchu was a charlatan and con man rather than a supervillain and in fact he was a Canadian married to a Chinese wife and only pretending to be Chinese himself; the grand criminal schemes attributed to him were mere myths, concocted either by himself or by the sensationalist press and publicity-seeking police officers, the latter partly motivated by anti-Chinese prejudice.

In other media

Film

Dr. Fu Manchu first appeared on the big screen in the British silent film series The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu (1923) starring Harry Agar Lyons as Dr. Fu Manchu, a series of 15 short feature films, each running around 20 minutes. Lyons returned to the role in The Further Mysteries of Dr. Fu Manchu (1924), which comprised eight additional short feature films.[18][19]

Dr. Fu Manchu made his American film debut in Paramount's early talkie, The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929) starring Warner Oland, soon to be known for his portrayal of Charlie Chan. Oland repeated the role in The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930) and Daughter of the Dragon (1931) as well as in the short film Murder Will Out (part of the omnibus film Paramount on Parade) in which Dr. Fu Manchu confronts both Philo Vance and Sherlock Holmes.[20]

The most controversial incarnation of the character was MGM's The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) starring Boris Karloff and Myrna Loy. At the time of its first release, the film was considered racist and offensive by representatives of the Chinese government. The film was suppressed for many years, but has been released on DVD uncut.[21]

Dr. Fu Manchu returned to the serial format in Republic Pictures' Drums of Fu Manchu (1940), a 15-episode serial considered to be one of the best the studio ever made. It was later edited and released as a feature film in 1943.

Other than an obscure, unauthorized Spanish spoof El Otro Fu Manchu (1946), the Devil Doctor was absent from the big screen for 25 years, until producer Harry Alan Towers began a series starring Christopher Lee in 1965. Towers and Lee would make five Dr. Fu Manchu films through to the end of the decade: The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966), The Vengeance of Fu Manchu (1967), The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968), and The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969).[22]

The character's last authorized film appearance was in the Peter Sellers spoof The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980), with Sellers featured in a double role as both Dr. Fu Manchu and Nayland Smith. The film bore little resemblance to any prior film or the original books. In the film, Dr. Fu Manchu claims he was known as "Fred" at public school, a reference to the character of "The Terrible Revenge of Fred Fu Manchu" from a 1955 episode of The Goon Show which had co-starred Sellers.[23]

Jess Franco, who had directed The Blood of Fu Manchu and The Castle of Fu Manchu, also directed The Girl From Rio, the second of three Harry Alan Towers films based on Rohmer's female Dr. Fu Manchu-like character, Sumuru. He later directed an unauthorized 1986 Spanish film featuring Dr. Fu Manchu's daughter, Esclavas del Crimen.[24]

In 2000, Lionsgate was developing a Fu Manchu reboot film, which was to have been directed by Álex de la Iglesia, and would have starred Antonio Banderas as an FBI agent on Manchu's trail.[25][26] The unproduced film was scrapped due to an escalating budget.[27]

In the film Grindhouse (2007), Nicolas Cage makes an uncredited comedic cameo appearance as Dr. Fu Manchu, during the "trailer" for the fake movie Werewolf Women of the SS, directed by Rob Zombie.

Television

A half-hour pilot was produced in 1952 for NBC's consideration starring Cedric Hardwicke as Sir Denis Nayland Smith, John Carradine as Dr. Fu Manchu, and Reed Hadley as Dr. John Petrie. NBC turned it down without broadcasting it, but it has been screened at special events.

The television arm of Republic Pictures produced a 13-episode syndicated series The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu (1956), starring Glen Gordon as Dr. Fu Manchu, Lester Matthews as Sir Denis Nayland Smith, and Clark Howat as Dr. John Petrie. The title sequence depicted Smith and Dr. Fu Manchu in a game of chess as the announcer stated that "the devil is said to play for men's souls. So does Dr. Fu Manchu, evil incarnate." At the conclusion of each episode, after Nayland Smith and Petrie had foiled Dr. Fu Manchu's latest fiendish scheme, Dr. Fu Manchu would be seen breaking a black chess piece in a fit of frustration (black king's bishop, always the same scene, repeated) just before the closing credits rolled. It was directed by Franklin Adreon, as well as William Witney. Dr. Fu Manchu was never allowed to succeed in this TV series. Unlike the Holmes/Watson type relationship of the films, the series featured Smith as a law enforcement officer and Petrie as a staff member for the Surgeon-General.[28]

Music

- American stoner rock band Fu Manchu was formed in Southern California in 1985.

- Desmond Dekker had a 1969 reggae song titled "Fu Man Chu".

- The Sparks song "Moustache" from the 1982 album Angst in My Pants includes a lyric "My Fu Manchu was real fine".[29]

- The Rockin' Ramrods had a 1965 song titled "Don't Fool With Fu Manchu".[30]

- Quebec rock singer Robert Charlebois included an epic three-part song titled "Fu Man Chu" on his 1972 album Charlebois.

- Russian hardbass artist XS Project has a song named "Fu Manchu".[31]

- American country music singer Tim McGraw published a song called "Live Like You Were Dying". The song references Dr. Fu Manchu in the lyric "I went two point seven seconds on a bull named Fu Manchu".[32]

- American country music singer Travis Tritt published a song called "It’s A Great Day To Be Alive". Dr. Fu Manchu's iconic mustache is referenced in the lyric "Might even grow me a Fu Manchu".[33]

- Japanese electronic music band Yellow Magic Orchestra published a song called "La Femme Chinoise", in which they reference the supervillain: "Fu Manchu and Susie Que and the girls of the floating world".[34]

- American rock musician Black Francis released a song entitled Fu Manchu on his 1993 solo album, which references both the style of mustache as well as the character after which it was named.

Radio

Dr. Fu Manchu's earliest radio appearances were on the Collier Hour 1927–1931 on the Blue Network. This was a radio program designed to promote Collier's magazine and presented weekly dramatizations of the current issue's stories and serials. Dr. Fu Manchu was voiced by Arthur Hughes. A self-titled show on CBS followed in 1932–33. John C. Daly, and later Harold Huber, played Dr. Fu Manchu.[35] In 2010 Fu Manchu's connections with Edinburgh University where he supposedly obtained a doctorate were investigated in a mockumentary by Miles Jupp for BBC Radio 4. Additionally, there were "pirate" broadcasts from the Continent into Britain, from Radio Luxembourg and Radio Lyons in 1936 through 1937. Frank Cochrane voiced Dr. Fu Manchu. The BBC produced a competing series, The Peculiar Case of the Poppy Club, starting in 1939. That same year, The Shadow of Fu Manchu aired in the United States as a thrice-weekly serial dramatizing the first nine novels.[36]

Comic strips

Dr. Fu Manchu was first brought to newspaper comic strips in a black and white daily comic strip drawn by Leo O'Mealia (1884-1960) that ran from 1931 to 1933. The strips were adaptations of the first two Dr. Fu Manchu novels and part of the third.[37][38] Unlike most other illustrators, O'Mealia drew Dr. Fu Manchu as a clean-shaven man with an abnormally large cranium. The strips were copyrighted by "Sax Rohmer and The Bell Syndicate, Inc.".[37] Two of the Dr. Fu Manchu comic strip storylines were reprinted in the 1989 book Fu Manchu: Two Complete Adventures.[39]

Between 1962 and 1973, the French newspaper Le Parisien Libéré published a comic strip by Juliette Benzoni (script) and Robert Bressy (art).[40]

Comic books

- Dr. Fu Manchu made his first comic book appearance in Detective Comics #17 and continued, as one feature among many in the anthology series, until #28. These were reprints of the earlier Leo O'Mealia strips. In 1943, the serial Drums of Fu Manchu was adapted by Spanish comic artist José Grau Hernández in 1943.[41] Original Dr. Fu Manchu stories in comics had to wait for Avon's one-shot The Mask of Dr. Fu Manchu in 1951 by Wally Wood.[38] A similar British one-shot, The Island of Fu Manchu, was published in 1956.

- In the 1970s, Dr. Fu Manchu appeared as the father of the superhero Shang-Chi in the Marvel Comics series Master of Kung Fu.[38][42] However, Marvel cancelled the book in 1983 and issues over licensing the character and concepts from the novels (such as his daughter Fah Lo Suee and adversaries Sir Denis Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie) have hampered Marvel's ability to both collect the series in trade paperback format and reference Dr. Fu Manchu as Shang-Chi's father. As such, the character is either never mentioned by name, or by an alias (such as "Mr. Han").[43] In Secret Avengers #6-10, writer Ed Brubaker officially sidestepped the entire issue via a storyline where the Shadow Council resurrect a zombified version of Dr. Fu Manchu, only to discover that "Dr. Fu Manchu" was only an alias; that Shang-Chi's father was really Zheng Zu, an ancient Chinese sorcerer who discovered the secret to immortality.[44]

- Dr. Fu Manchu appears as an antagonist in Alan Moore's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Simply called "the Doctor", he is the first to steal the Cavorite that the League is sent to retrieve. He is apparently killed in the climatic battle with Moriarty.[45]

See also

References

- "Fu Manchu and China: Was the 'yellow peril incarnate' really appallingly racist?". The Independent. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Rovin, Jeff (1987). The Encyclopedia of Supervillains. New York: Facts on File. pp. 93–94. ISBN 0-8160-1356-X.

- Seshagiri, Urmila (2006). "Modernity's (Yellow) Perils: Dr. Fu-Manchu and English Race Paranoia". Cultural Critique (#62): 162–194. JSTOR 4489239.

- "The racist curse of Fu Manchu back in spotlight after Chevrolet ad". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Kinkley, Jeffrey C. (1 December 2016). "Book review: The Yellow Peril: Dr. Fu Manchu and the Rise of Chinaphobia by Christopher Frayling". Historian. New York. 78 (#4): 832–833. doi:10.1111/hisn.12410. ISSN 1540-6563.

- Christopher Frayling, quoted in "Fu Manchu", in Newman, Kim (ed.), The BFI Companion to Horror. London: Cassell (1996), pp. 131–132) . ISBN 0-304-33216-X

- Gregory William Mank, Hollywood Cauldron: 13 Horror Films from the Genres's Golden Age, McFarland, 2001 (pp.53–89) ISBN 0-7864-1112-0

- Jeffrey Richards. China and the Chinese in Popular Film: From Fu Manchu to Charlie Chan. p. 44

- Young, Ian (1 May 2013). "GM pulls 'racist' Chevrolet 'ching-ching, chop suey' ad". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Barker, Phil (2015). Lord of Strange Deaths: The Fiendish World of Sax Rohmer. London: Strange Attractor. ISBN 978-1907222252.

- Barker, Phil (20 October 2015). "Fu Manchu and China: Was the 'yellow peril incarnate' really appallingly racist?". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- "Fu Manchu". Lexico. Oxford Dictionaries and Dictionary.com. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Frayling, C. (2014). The Yellow Peril: Dr. Fu Manchu and the Rise of Chinaphobia. New York: Thames & Hudson, Inc

- Smith, A. H. (1894). Chinese characteristics (2nd rev. ed.). London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner. pp. 242

- "Blood of Fu Manchu". Braineater.com.

- "FuMunChews". Njedge.net. 16 September 1976.

- James St. Clair (24 April 2011), Fiendish Dr. Wu, retrieved 9 February 2018

- "BFI Screenonline: Mystery of Dr Fu Manchu, The (1923)". screenonline.org.uk.

- Workman, Christopher; Howarth, Troy (2016). "Tome of Terror: Horror Films of the Silent Era". Midnight Marquee Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-1936168-68-2.

- Hanke, Ken (14 January 2011). Charlie Chan at the Movies: History, Filmography, and Criticism. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8661-8.

- Hanke, Ken (14 January 2011). Charlie Chan at the Movies: History, Filmography, and Criticism. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8661-8.

- "BFI Screenonline: Face of Fu Manchu, The (1965)". screenonline.org.uk.

- p. 210, Lewis, Roger, The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, Random House 1995

- Hanke, Ken (14 January 2011). Charlie Chan at the Movies: History, Filmography, and Criticism. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8661-8.

- Green, Willow (27 November 2000). "Banderas Fights Fu Manchu". Empire.

- "Banderas Circles Role in Fu Manchu". Variety. 26 November 2000.

- "The Fu Manchu That Almost Was". Black Gate. 3 June 2016.

- Hanke, Ken (14 January 2011). Charlie Chan at the Movies: History, Filmography, and Criticism. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8661-8.

- https://genius.com/8830275. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . 10 April 2010 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2oUnuohuEE. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - https://soundcloud.com/xsproject/fu-manchu. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Tim McGraw - Live Like You Were Dying Lyrics". MetroLyrics. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Travis Tritt – It's a Great Day to Be Alive, retrieved 16 March 2018

- "Yellow Magic Orchestra - La Femme Chinoise Lyrics". MetroLyrics. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Richards, Jeffrey (9 November 2016). China and the Chinese in Popular Film: From Fu Manchu to Charlie Chan. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781786720641.

- Cox, Jim, Radio Crime Fighters. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002. ISBN 0-7864-1390-5

- Goulart, Ron (1995). The Funnies, 100 Years of American Comic Strips. Holbrook, Mass: Adams Publishing. pp. 104, 106. ISBN 978-0944735244.

- "Fu Manchu in Comics". Blackgate.com. 23 July 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Sax Rohmer, Leo O'Mealia and Tom Mason, Fu Manchu: Two Complete Adventures. Newbury Park, CA :Malibu Graphics, 1989. ISBN 094473524X

- "Le retour de Fu-Manchu, et de Pressibus… !". Bdzoom.com. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Porcel Torrens, Pedro (2002). La historia del tebeo valenciano. Edicions de Ponent. pp. 47–55, 69. ISBN 84-89929-38-6.

- "Blogging Marvel's Master of Kung Fu, Part One". Blackgate.com. 12 June 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Black Panther (vol. 4) #11

- "Benson Unleashes Shang-Chi's "Deadly Hands of Kung Fu"". Cbr.com. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

External links

- Fu Manchu on IMDb

- "The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu" (1956 TV Series)

- The Page of Fu Manchu

- Fu Manchu at seriesbooks.info

- Fu Manchu series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Fu Manchu on Public Domain Super Heroes, an external wiki

- Fu Manchu at Comic Vine

- The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu by Sax Rohmer

- The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu by Sax Rohmer

- A database and cover gallery of Fu Manchu comic book appearances

- Theater of the Ears: The Shadow of Fu Manchu Radio Dramas

- The Chronology of Fu Manchu

- The Shang Chi Chronology

- The Dynasty of Fu Manchu:A Look at the Genealogies of the Heroes and Villains of the Fu Manchu Series

- Dr. Fu Manchu International Heroes

- Fu Manchu's French comic strips on Cool French Comics

- Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril https://web.archive.org/web/20110815072125/http://dspace.wul.waseda.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2065/10005/1/40050_3_2.pdf

- Fu Manchu in Edinburgh (BBC Radio 4 programme)