California Gold Rush

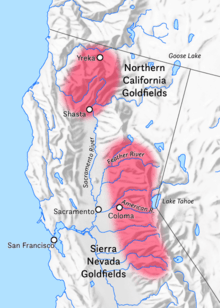

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California.[1] The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the United States and abroad.[2] The sudden influx of gold into the money supply reinvigorated the American economy, and the sudden population increase allowed California to go rapidly to statehood, in the Compromise of 1850. The Gold Rush had severe effects on Native Californians and accelerated the Native American population's decline from disease, starvation and the California Genocide. By the time it ended, California had gone from a thinly populated ex-Mexican territory, to having one of its first two U.S. Senators, John C. Frémont, selected to be the first presidential nominee for the new Republican Party, in 1856.

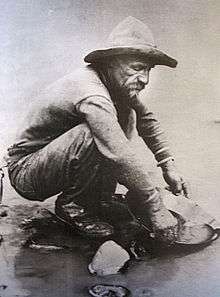

Prospectors working California gold placer deposits in 1850 | |

| Date | January 24, 1848–1855 |

|---|---|

| Location | Sierra Nevada and Northern California goldfields |

| Coordinates | 38°48′N 120°53′W |

| Participants | 300,000 prospectors |

| Outcome | California becomes a U.S. state California Genocide occurs |

| Periods in United States history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The effects of the Gold Rush were substantial. Whole indigenous societies were attacked and pushed off their lands by the gold-seekers, called "forty-niners" (referring to 1849, the peak year for Gold Rush immigration). Outside of California, the first to arrive were from Oregon, the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), and Latin America in late 1848. Of the approximately 300,000 people who came to California during the Gold Rush, about half arrived by sea and half came overland on the California Trail and the Gila River trail; forty-niners often faced substantial hardships on the trip. While most of the newly arrived were Americans, the gold rush attracted thousands from Latin America, Europe, Australia, and China. Agriculture and ranching expanded throughout the state to meet the needs of the settlers. San Francisco grew from a small settlement of about 200 residents in 1846 to a boomtown of about 36,000 by 1852. Roads, churches, schools and other towns were built throughout California. In 1849 a state constitution was written. The new constitution was adopted by referendum vote, and the future state's interim first governor and legislature were chosen. In September 1850, California became a state.

At the beginning of the Gold Rush, there was no law regarding property rights in the goldfields and a system of "staking claims" was developed. Prospectors retrieved the gold from streams and riverbeds using simple techniques, such as panning. Although the mining caused environmental harm, more sophisticated methods of gold recovery were developed and later adopted around the world. New methods of transportation developed as steamships came into regular service. By 1869, railroads were built from California to the eastern United States. At its peak, technological advances reached a point where significant financing was required, increasing the proportion of gold companies to individual miners. Gold worth tens of billions of today's US dollars was recovered, which led to great wealth for a few, though many who participated in the California Gold Rush earned little more than they had started with.

History

The Mexican–American War ended on February 3, 1848, although California was a de facto American possession before that. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided for, among other things, the formal transfer of Upper California to the United States. The California Gold Rush began at Sutter's Mill, near Coloma.[3] On January 24, 1848, James W. Marshall, a foreman working for Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, found shiny metal in the tailrace of a lumber mill Marshall was building for Sutter on the American River.[4] Marshall brought what he found to John Sutter, and the two privately tested the metal. After the tests showed that it was gold, Sutter expressed dismay: he wanted to keep the news quiet because he feared what would happen to his plans for an agricultural empire if there were a mass search for gold.[5]

Discovery announced

Rumors of the discovery of gold were confirmed in March 1848 by San Francisco newspaper publisher and merchant Samuel Brannan. Brannan hurriedly set up a store to sell gold prospecting supplies,[6] and walked through the streets of San Francisco, holding aloft a vial of gold, shouting "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!"[7]

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper on the East Coast to report the discovery of gold. On December 5, 1848, US President James Polk confirmed the discovery of gold in an address to Congress.[8] As a result, individuals seeking to benefit from the gold rush—later called the "forty-niners"—began moving to the Gold Country of California or "Mother Lode" from other countries and from other parts of the United States. As Sutter had feared, his business plans were ruined after his workers left in search of gold, and squatters took over his land and stole his crops and cattle.[9]

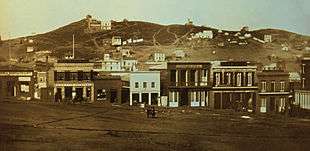

San Francisco had been a tiny settlement before the rush began. When residents learned about the discovery, it at first became a ghost town of abandoned ships and businesses,[10] but then boomed as merchants and new people arrived. The population of San Francisco increased quickly from about 1,000[11] in 1848 to 25,000 full-time residents by 1850.[12] Miners lived in tents, wood shanties, or deck cabins removed from abandoned ships.[13]

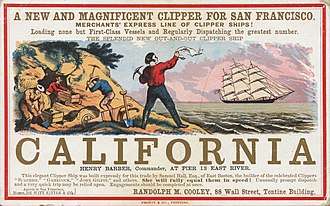

Transportation to California

In what has been referred to as the "first world-class gold rush,"[14] there was no easy way to get to California; forty-niners faced hardship and often death on the way. At first, most Argonauts, as they were also known, traveled by sea. From the East Coast, a sailing voyage around the tip of South America would take four to five months,[15] and cover approximately 18,000 nautical miles (21,000 mi; 33,000 km). An alternative was to sail to the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama, take canoes and mules for a week through the jungle, and then on the Pacific side, wait for a ship sailing for San Francisco.[16] There was also a route across Mexico starting at Veracruz. The companies providing such transportation created vast wealth among their owners and included the U.S. Mail Steamship Company, the federally subsidized Pacific Mail Steamship Company, and the Accessory Transit Company. Many gold-seekers took the overland route across the continental United States, particularly along the California Trail.[17] Each of these routes had its own deadly hazards, from shipwreck to typhoid fever and cholera.[18] In the early years of the rush, much of the population growth in the San Francisco area was due to steamship travel from New York City through overland portages in Nicaragua and Panama and then back up by steamship to San Francisco.[19]

Supplies and goods needed

Supply ships arrived in San Francisco with goods to supply the needs of the growing population. When hundreds of ships were abandoned after their crews deserted to go into the goldfields, many ships were converted to warehouses, stores, taverns, hotels, and one into a jail.[20] As the city expanded and new places were needed on which to build, many ships were destroyed and used as landfill.[20]

Northern California strikes

Within a few years, there was an important but lesser-known surge of prospectors into far Northern California, specifically into present-day Siskiyou, Shasta and Trinity Counties.[21] Discovery of gold nuggets at the site of present-day Yreka in 1851 brought thousands of gold-seekers up the Siskiyou Trail[22] and throughout California's northern counties.[23]

Settlements of the Gold Rush era, such as Portuguese Flat on the Sacramento River, sprang into existence and then faded. The Gold Rush town of Weaverville on the Trinity River today retains the oldest continuously used Taoist temple in California, a legacy of Chinese miners who came. While there are not many Gold Rush era ghost towns still in existence, the remains of the once-bustling town of Shasta have been preserved in a California State Historic Park in Northern California.[24]

Gold was also discovered in Southern California but on a much smaller scale. The first discovery of gold, at Rancho San Francisco in the mountains north of present-day Los Angeles, had been in 1842, six years before Marshall's discovery, while California was still part of Mexico.[25] However, these first deposits, and later discoveries in Southern California mountains, attracted little notice and were of limited consequence economically.[25]

Indigenous peoples driven out

By 1850, most of the easily accessible gold had been collected, and attention turned to extracting gold from more difficult locations. Faced with gold increasingly difficult to retrieve, Americans began to drive out foreigners to get at the most accessible gold that remained. The new California State Legislature passed a foreign miners tax of twenty dollars per month ($610 per month as of 2020), and American prospectors began organized attacks on foreign miners, particularly Latin Americans and Chinese.[26]

In addition, the huge numbers of newcomers were driving Native Americans out of their traditional hunting, fishing and food-gathering areas. To protect their homes and livelihood, some Native Americans responded by attacking the miners. This provoked counter-attacks on native villages. The Native Americans, out-gunned, were often slaughtered.[27] Those who escaped massacres were many times unable to survive without access to their food-gathering areas, and they starved to death. Novelist and poet Joaquin Miller vividly captured one such attack in his semi-autobiographical work, Life Amongst the Modocs.[28]

Earlier discoveries of gold

The first gold found in California was made on March 9, 1842. Francisco Lopez, a native California, was searching for stray horses. He stopped on the bank of a small creek in what later was known as Placerita Canyon, about 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the present-day Newhall, California, and about 35 miles (56 km) northwest of Los Angeles. While the horses grazed, Lopez dug up some wild onions and found a small gold nugget in the roots among the onion bulbs. He looked further and found more gold.[29]

Lopez took the gold to authorities who confirmed its worth. Lopez and others began to search for other streambeds with gold deposits in the area. They found several in the northeastern section of the forest, within present-day Ventura County. In 1843 he found gold in San Feliciano Canyon near his first discovery. Mexican miners from Sonora worked the placer deposits until 1846, when the Californios began to agitate for independence from Mexico, and the Bear Flag Revolt caused many Mexicans to leave California.[29]

Forty-niners

The first people to rush to the goldfields, beginning in the spring of 1848, were the residents of California themselves—primarily agriculturally oriented Americans and Europeans living in Northern California, along with Native Americans and some Californios (Spanish-speaking Californians).[30] These first miners tended to be families in which everyone helped in the effort. Women and children of all ethnicities were often found panning next to the men. Some enterprising families set up boarding houses to accommodate the influx of men; in such cases, the women often brought in steady income while their husbands searched for gold.[31]

Word of the Gold Rush spread slowly at first. The earliest gold-seekers were people who lived near California or people who heard the news from ships on the fastest sailing routes from California. The first large group of Americans to arrive were several thousand Oregonians who came down the Siskiyou Trail.[32] Next came people from the Sandwich Islands, and several thousand Latin Americans, including people from Mexico, from Peru and from as far away as Chile,[33] both by ship and overland.[34] By the end of 1848, some 6,000 Argonauts had come to California.[34]

Only a small number (probably fewer than 500) traveled overland from the United States that year.[34] Some of these "forty-eighters",[35] as the earliest gold-seekers were sometimes called, were able to collect large amounts of easily accessible gold—in some cases, thousands of dollars worth each day.[36][37] Even ordinary prospectors averaged daily gold finds worth 10 to 15 times the daily wage of a laborer on the East Coast. A person could work for six months in the goldfields and find the equivalent of six years' wages back home.[38] Some hoped to get rich quick and return home, and others wished to start businesses in California.

By the beginning of 1849, word of the Gold Rush had spread around the world, and an overwhelming number of gold-seekers and merchants began to arrive from virtually every continent. The largest group of forty-niners in 1849 were Americans, arriving by the tens of thousands overland across the continent and along various sailing routes[39] (the name "forty-niner" was derived from the year 1849). Many from the East Coast negotiated a crossing of the Appalachian Mountains, taking to riverboats in Pennsylvania, poling the keelboats to Missouri River wagon train assembly ports, and then travelling in a wagon train along the California Trail. Many others came by way of the Isthmus of Panama and the steamships of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Australians[40] and New Zealanders picked up the news from ships carrying Hawaiian newspapers, and thousands, infected with "gold fever", boarded ships for California.[41]

Forty-niners came from Latin America, particularly from the Mexican mining districts near Sonora and Chile.[41][42] Gold-seekers and merchants from Asia, primarily from China,[43] began arriving in 1849, at first in modest numbers to Gum San ("Gold Mountain"), the name given to California in Chinese.[44] The first immigrants from Europe, reeling from the effects of the Revolutions of 1848 and with a longer distance to travel, began arriving in late 1849, mostly from France,[45] with some Germans, Italians, and Britons.[39]

It is estimated that approximately 90,000 people arrived in California in 1849—about half by land and half by sea.[46] Of these, perhaps 50,000 to 60,000 were Americans, and the rest were from other countries.[39] By 1855, it is estimated at least 300,000 gold-seekers, merchants, and other immigrants had arrived in California from around the world.[47] The largest group continued to be Americans, but there were tens of thousands each of Mexicans, Chinese, Britons, Australians,[48] French, and Latin Americans,[49] together with many smaller groups of miners, such as African Americans, Filipinos, Basques[50] and Turks.[51][52]

People from small villages in the hills near Genova, Italy were among the first to settle permanently in the Sierra Nevada foothills; they brought with them traditional agricultural skills, developed to survive cold winters.[53] A modest number of miners of African ancestry (probably less than 4,000)[54] had come from the Southern States,[55] the Caribbean and Brazil.[56]

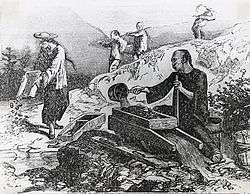

A number of immigrants were from China. Several hundred Chinese arrived in California in 1849 and 1850, and in 1852 more than 20,000 landed in San Francisco.[57] Their distinctive dress and appearance was highly recognizable in the goldfields. Chinese miners suffered enormously, enduring violent racism from white miners who aimed their frustrations at foreigners. To this day, there has been no justice for known victims. Further animosity toward the Chinese led to legislation such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and Foreign Miners Tax.[58][57]

There were also women in the Gold Rush. However, their numbers were small. Of the 40,000 people who arrived by ship in the San Francisco harbor in 1849, only 700 were women (including poor women, wealthy women, entrepreneurs, prostitutes, single women and married women).[59] They were of various ethnicities including Anglo-American, African-American,[60] Hispanic, Native, European, Chinese, and Jewish. The reasons they came varied: some came with their husbands, refusing to be left behind to fend for themselves, some came because their husbands sent for them, and others came (singles and widows) for the adventure and economic opportunities.[61] On the trail many people died from accidents, cholera, fever, and myriad other causes, and many women became widows before even setting eyes on California. While in California, women became widows quite frequently due to mining accidents, disease, or mining disputes of their husbands. Life in the goldfields offered opportunities for women to break from their traditional work.[62][63]

Legal rights

When the Gold Rush began, the California goldfields were peculiarly lawless places.[64] When gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill, California was still technically part of Mexico, under American military occupation as the result of the Mexican–American War. With the signing of the treaty ending the war on February 2, 1848, California became a possession of the United States, but it was not a formal "territory" and did not become a state until September 9, 1850. California existed in the unusual condition of a region under military control. There was no civil legislature, executive or judicial body for the entire region.[65] Local residents operated under a confusing and changing mixture of Mexican rules, American principles, and personal dictates. Lax enforcement of federal laws, such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, encouraged the arrival of free blacks and escaped slaves.[52]

While the treaty ending the Mexican–American War obliged the United States to honor Mexican land grants,[66] almost all the goldfields were outside those grants. Instead, the goldfields were primarily on "public land", meaning land formally owned by the United States government.[67] However, there were no legal rules yet in place,[64] and no practical enforcement mechanisms.[68]

The benefit to the forty-niners was that the gold was simply "free for the taking" at first. In the goldfields at the beginning, there was no private property, no licensing fees, and no taxes.[69][70] The miners informally adapted Mexican mining law that had existed in California.[71] For example, the rules attempted to balance the rights of early arrivers at a site with later arrivers; a "claim" could be "staked" by a prospector, but that claim was valid only as long as it was being actively worked.[64][72][73]

Miners worked at a claim only long enough to determine its potential. If a claim was deemed as low-value—as most were—miners would abandon the site in search for a better one. In the case where a claim was abandoned or not worked upon, other miners would "claim-jump" the land. "Claim-jumping" meant that a miner began work on a previously claimed site.[72][73] Disputes were often handled personally and violently, and were sometimes addressed by groups of prospectors acting as arbitrators.[67][72][73] This often led to heightened ethnic tensions.[74] In some areas the influx of many prospectors could lead to a reduction of the existing claim size by simple pressure.[75]

Development of gold-recovery techniques

Four hundred million years ago, California lay at the bottom of a large sea; underwater volcanoes deposited lava and minerals (including gold) onto the sea floor. By tectonic forces these minerals and rocks came to the surface of the Sierra Nevada,[76] and eroded. Water carried the exposed gold downstream and deposited it in quiet gravel beds along the sides of old rivers and streams.[77][78] The forty-niners first focused their efforts on these deposits of gold.[79]

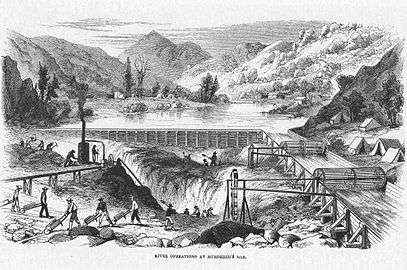

Because the gold in the California gravel beds was so richly concentrated, early forty-niners were able to retrieve loose gold flakes and nuggets with their hands, or simply "pan" for gold in rivers and streams.[80][81] Panning cannot take place on a large scale, and industrious miners and groups of miners graduated to placer mining, using "cradles" and "rockers" or "long-toms"[82] to process larger volumes of gravel.[83] Miners would also engage in "coyoteing",[84] a method that involved digging a shaft 6 to 13 meters (20 to 43 ft) deep into placer deposits along a stream. Tunnels were then dug in all directions to reach the richest veins of pay dirt.

In the most complex placer mining, groups of prospectors would divert the water from an entire river into a sluice alongside the river, and then dig for gold in the newly exposed river bottom.[85] Modern estimates are that as much as 12 million ounces[86] (370 t) of gold were removed in the first five years of the Gold Rush.[87]

In the next stage, by 1853, hydraulic mining was used on ancient gold-bearing gravel beds on hillsides and bluffs in the goldfields.[88] In a modern style of hydraulic mining first developed in California, and later used around the world, a high-pressure hose directed a powerful stream or jet of water at gold-bearing gravel beds.[89] The loosened gravel and gold would then pass over sluices, with the gold settling to the bottom where it was collected. By the mid-1880s, it is estimated that 11 million ounces (340 t) of gold (worth approximately US$15 billion at December 2010 prices) had been recovered by hydraulic mining.[87]

A byproduct of these extraction methods was that large amounts of gravel, silt, heavy metals, and other pollutants went into streams and rivers.[90] As of 1999 many areas still bear the scars of hydraulic mining, since the resulting exposed earth and downstream gravel deposits do not support plant life.[91]

After the Gold Rush had concluded, gold recovery operations continued. The final stage to recover loose gold was to prospect for gold that had slowly washed down into the flat river bottoms and sandbars of California's Central Valley and other gold-bearing areas of California (such as Scott Valley in Siskiyou County). By the late 1890s, dredging technology (also invented in California) had become economical,[92] and it is estimated that more than 20 million ounces (620 t) were recovered by dredging.[87]

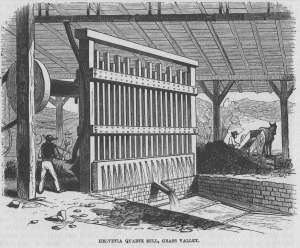

Both during the Gold Rush and in the decades that followed, gold-seekers also engaged in "hard-rock" mining, extracting the gold directly from the rock that contained it (typically quartz), usually by digging and blasting to follow and remove veins of the gold-bearing quartz.[93] Once the gold-bearing rocks were brought to surface, the rocks were crushed and the gold separated, either using separation in water, using its density difference from quartz sand, or by washing the sand over copper plates coated with mercury (with which gold forms an amalgam). Loss of mercury in the amalgamation process was a source of environmental contamination.[94] Eventually, hard-rock mining became the single largest source of gold produced in the Gold Country.[87][95] The total production of gold in California from then till now is estimated at 118 million ounces (3700 t).[96]

Forty-niner panning for gold

Forty-niner panning for gold Sluice for separation of gold from dirt using water

Sluice for separation of gold from dirt using water Excavating a riverbed after the water has been diverted

Excavating a riverbed after the water has been diverted Crushing quartz ore prior to washing out gold

Crushing quartz ore prior to washing out gold Excavating a gravel bed with jets, circa 1863

Excavating a gravel bed with jets, circa 1863

Profits

Recent scholarship confirms that merchants made far more money than miners during the Gold Rush.[97][98] The wealthiest man in California during the early years of the rush was Samuel Brannan, a tireless self-promoter, shopkeeper and newspaper publisher.[99] Brannan opened the first supply stores in Sacramento, Coloma, and other spots in the goldfields. Just as the rush began he purchased all the prospecting supplies available in San Francisco and re-sold them at a substantial profit.[99]

Some gold-seekers made a significant amount of money.[100] On average, half the gold-seekers made a modest profit, after taking all expenses into account; economic historians have suggested that white miners were more successful than black, Indian, or Chinese miners.[101] However, taxes such as the California foreign miners tax passed in 1851, targeted mainly Latino miners[102] and kept them from making as much money as whites, who did not have any taxes imposed on them. In California most late arrivals made little or wound up losing money.[97] Similarly, many unlucky merchants set up in settlements which disappeared, or which succumbed to one of the calamitous fires that swept the towns that sprang up. By contrast, a businessman who went on to great success was Levi Strauss, who first began selling denim overalls in San Francisco in 1853.[103]

Other businessmen reaped great rewards in retail, shipping, entertainment, lodging,[104] or transportation.[105] Boardinghouses, food preparation, sewing, and laundry were highly profitable businesses often run by women (married, single, or widowed) who realized men would pay well for a service done by a woman. Brothels also brought in large profits, especially when combined with saloons and gaming houses.[106]

By 1855, the economic climate had changed dramatically. Gold could be retrieved profitably from the goldfields only by medium to large groups of workers, either in partnerships or as employees. By the mid-1850s, it was the owners of these gold-mining companies who made the money. Also, the population and economy of California had become large and diverse enough that money could be made in a wide variety of conventional businesses.[107]

Path of the gold

Once extracted, the gold itself took many paths. First, much of the gold was used locally to purchase food, supplies and lodging for the miners. It also went towards entertainment, which consisted of anything from a traveling theater to alcohol, gambling, and prostitutes. These transactions often took place using the recently recovered gold, carefully weighed out.[108][109] These merchants and vendors in turn used the gold to purchase supplies from ship captains or packers bringing goods to California.[110]

The gold then left California aboard ships or mules to go to the makers of the goods from around the world. A second path was the Argonauts themselves who, having personally acquired a sufficient amount, sent the gold home, or returned home taking with them their hard-earned "diggings". For example, one estimate is that some US$80 million worth of California gold (equivalent to US$2.2 billion today) was sent to France by French prospectors and merchants.[111]

A majority of the gold went back to New York City brokerage houses.[19]

As the Gold Rush progressed, local banks and gold dealers issued "banknotes" or "drafts"—locally accepted paper currency—in exchange for gold,[112] and private mints created private gold coins.[113] With the building of the San Francisco Mint in 1854, gold bullion was turned into official United States gold coins for circulation.[114] The gold was also later sent by California banks to U.S. national banks in exchange for national paper currency to be used in the booming California economy.[115]

Near-term effects

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of new people in California within a few years, compared to a population of some 15,000 Europeans and Californios beforehand,[116] had many dramatic effects.[117]

A 2017 study attributes the record-long economic expansion of the United States in the recession-free period of 1841–1856 primarily to "a boom in transportation-goods investment following the discovery of gold in California."[118]

Development of government and commerce

The Gold Rush propelled California from a sleepy, little-known backwater to a center of the global imagination and the destination of hundreds of thousands of people. The new immigrants often showed remarkable inventiveness and civic-mindedness. For example, in the midst of the Gold Rush, towns and cities were chartered, a state constitutional convention was convened, a state constitution written, elections held, and representatives sent to Washington, D.C. to negotiate the admission of California as a state.[119]

Large-scale agriculture (California's second "Gold Rush"[120]) began during this time.[121] Roads, schools, churches,[122] and civic organizations quickly came into existence.[119] The vast majority of the immigrants were Americans.[123] Pressure grew for better communications and political connections to the rest of the United States, leading to statehood for California on September 9, 1850, in the Compromise of 1850 as the 31st state of the United States.

Between 1847 and 1870, the population of San Francisco increased from 500 to 150,000.[124] The Gold Rush wealth and population increase led to significantly improved transportation between California and the East Coast. The Panama Railway, spanning the Isthmus of Panama, was finished in 1855.[125] Steamships, including those owned by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, began regular service from San Francisco to Panama, where passengers, goods and mail would take the train across the Isthmus and board steamships headed to the East Coast. One ill-fated journey, that of the S.S. Central America,[126] ended in disaster as the ship sank in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas in 1857, with approximately three tons of California gold aboard.[127][128]

Impact on Native Americans

The human and environmental costs of the Gold Rush were substantial. Native Americans, dependent on traditional hunting, gathering and agriculture, became the victims of starvation and disease, as gravel, silt and toxic chemicals from prospecting operations killed fish and destroyed habitats.[90][91] The surge in the mining population also resulted in the disappearance of game and food gathering locales as gold camps and other settlements were built amidst them. Later farming spread to supply the settlers' camps, taking more land away from the Native Americans.[129]

In some areas, systematic attacks against tribespeople in or near mining districts occurred. Various conflicts were fought between natives and settlers.[130] Miners often saw Native Americans as impediments to their mining activities.[131] Ed Allen, interpretive lead for Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park, reported that there were times when miners would kill up to 50 or more Natives in one day.[132] Retribution attacks on solitary miners could result in larger scale attacks against Native populations, at times tribes or villages not involved in the original act.[133] During the 1852 Bridge Gulch Massacre, a group of settlers attacked a band of Wintu Indians in response to the killing of a citizen named J. R. Anderson. After his killing, the sheriff led a group of men to track down the Indians, whom the men then attacked. Only three children survived the massacre that was against a different band of Wintu than the one that had killed Anderson.[134]

Historian Benjamin Madley recorded the numbers of killings of California Indians between 1846 and 1873 and estimated that during this period at least 9,400 to 16,000 California Indians were killed by non-Indians, mostly occurring in more than 370 massacres (defined as the "intentional killing of five or more disarmed combatants or largely unarmed noncombatants, including women, children, and prisoners, whether in the context of a battle or otherwise").[135] According to demographer Russell Thornton, between 1849 and 1890, the Indigenous population of California fell below 20,000 – primarily because of the killings.[136] According to the government of California, some 4,500 Native Americans suffered violent deaths between 1849 and 1870.[137] Furthermore, California stood in opposition of ratifying the eighteen treaties signed between tribal leaders and federal agents in 1851.[138] The state government, in support of miner activities funded and supported death squads, appropriating over 1 million dollars towards the funding and operation of the paramilitary organizations.[139] Peter Burnett, California's first governor declared that California was a battleground between the races and that there were only two options towards California Indians, extermination or removal. "That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct, must be expected. While we cannot anticipate the result with but painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power and wisdom of man to avert." For Burnett, like many of his contemporaries, the genocide was part of God's plan, and it was necessary for Burnett's constituency to move forward in California.[140] The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, passed on April 22, 1850 by the California Legislature, allowed settlers to capture and use Native people as bonded workers, prohibited Native peoples' testimony against settlers, and allowed the adoption of Native children by settlers, often for labor purposes.[141]

After the initial boom had ended, explicitly anti-foreign and racist attacks, laws and confiscatory taxes sought to drive out foreigners—not just Native Americans—from the mines, especially the Chinese and Latin American immigrants mostly from Sonora, Mexico and Chile.[57][142] The toll on the American immigrants was severe as well: one in twelve forty-niners perished, as the death and crime rates during the Gold Rush were extraordinarily high, and the resulting vigilantism also took its toll.[143][144]

World-wide economic stimulation

| Year | Grains | Flour |

| 1848 | 3000 | n/a |

| 1849 | 87,000 | 69,000 |

| 1850 | 277,000 | 221,000 |

| 1854 | 63,000 | 50,000 |

The Gold Rush stimulated economies around the world as well. Farmers in Chile, Australia, and Hawaii found a huge new market for their food; British manufactured goods were in high demand; clothing and even prefabricated houses arrived from China.[146] The return of large amounts of California gold to pay for these goods raised prices and stimulated investment and the creation of jobs around the world.[147] Australian prospector Edward Hargraves, noting similarities between the geography of California and his home country, returned to Australia to discover gold and spark the Australian gold rushes.[148] Preceding the Gold Rush, the United States was on a bi-metallic standard, but the sudden increase in physical gold supply increased the relative value of physical silver and drove silver money from circulation. The increase in gold supply also created a monetary supply shock.[149]

Within a few years after the end of the Gold Rush, in 1863, the groundbreaking ceremony for the western leg of the First Transcontinental Railroad was held in Sacramento. The line's completion, some six years later, financed in part with Gold Rush money,[150] united California with the central and eastern United States. Travel that had taken weeks or even months could now be accomplished in days.[151]

Longer-term effects

California's name became indelibly connected with the Gold Rush, and fast success in a new world became known as the "California Dream."[152] California was perceived as a place of new beginnings, where great wealth could reward hard work and good luck. Historian H. W. Brands noted that in the years after the Gold Rush, the California Dream spread across the nation:

The old American Dream ... was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin's "Poor Richard"... of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream ... became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter's Mill.[153]

Overnight California gained the international reputation as the "golden state".[154] Generations of immigrants have been attracted by the California Dream. California farmers,[155] oil drillers,[156] movie makers,[157] airplane builders,[158] computer and microchip makers, and "dot-com" entrepreneurs have each had their boom times in the decades after the Gold Rush.[159]

Included among the modern legacies of the California Gold Rush are the California state motto, "Eureka" ("I have found it"), Gold Rush images on the California State Seal,[160] and the state nickname, "The Golden State", as well as place names, such as Placer County, Rough and Ready, Placerville (formerly named "Dry Diggings" and then "Hangtown" during rush time), Whiskeytown, Drytown, Angels Camp, Happy Camp, and Sawyers Bar. The San Francisco 49ers National Football League team, and the similarly named athletic teams of California State University, Long Beach, are named for the prospectors of the California Gold Rush.

In addition, the standard route shield of state highways in California is in the shape of a miner's spade to honor the California Gold Rush.[161][162] Today, the aptly named State Route 49 travels through the Sierra Nevada foothills, connecting many Gold Rush-era towns such as Placerville, Auburn, Grass Valley, Nevada City, Coloma, Jackson, and Sonora.[163] This state highway also passes very near Columbia State Historic Park, a protected area encompassing the historic business district of the town of Columbia; the park has preserved many Gold Rush-era buildings, which are presently occupied by tourist-oriented businesses.

Cultural references

- The literary history of the Gold Rush is reflected in the works of Mark Twain (The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County), Bret Harte (A Millionaire of Rough-and-Ready), Joaquin Miller (Life Amongst the Modocs), and many others.[28][164]

- The American football team San Francisco 49ers are named in honor of the "forty-niners" of 1849.

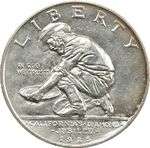

- The 1925 California Diamond Jubilee half dollar features a Forty-niner panning for gold.

- A number of animated cartoons satirized the California Gold Rush, including Gold Rush Daze (Warner Bros., 1939), 14 Carrot Rabbit (Warner Bros., 1952) and Barbary Coast Bunny (Warner Bros., 1956).

See also

- Barbary Coast

- California Mining and Mineral Museum

- Colorado Gold Rush

- Klondike Gold Rush

- Witwatersrand Gold Rush

Notes

- "[E]vents from January 1848 through December 1855 [are] generally acknowledged as the 'Gold Rush'. After 1855, California gold mining changed and is outside the 'rush' era.""The Gold Rush of California: A Bibliography of Periodical Articles". California State University, Stanislaus. 2002. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- "California Gold Rush, 1848–1864". Learn California.org, a site designed for the Secretary of State of California. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- For a detailed map, see California Historic Gold Mines Archived December 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, published by the State of California. Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 32-34.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 39-41.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 60.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 55-56.

- Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 80.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 103-105.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 59-60.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 51. "800 residents"

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 187.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 126.

- Hill, Mary (1999), p. 1

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 103-121

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 75–85. Another route across Nicaragua was developed in 1851; it was not as popular as the Panama option. Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 252-253.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 5.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 101, p. 107.

- Stiles, T. J. (2009)

- Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 80; "Shipping is the Foundation of San Francisco—Literally". Oakland Museum of California. 1998. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 363-366.

- Dillon, Richard (1975), pp. 361-362

- Wells, Harry (1881), p. 60-64.

- The buildings of Bodie, the best-known ghost town in California, date from the 1870s and later, well after the end of the Gold Rush.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 3.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 9.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 8.

- Miller, Joaquin (1873).

- Blakely, Jim (1985)

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 43-46.

- Moynihan, Ruth B., Armitage, Susan, and Dichamp, Christiane Fischer (eds.) (1990). p. 3.

- Starr, Kevin (2000), pp. 50-54

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 48–53.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 50–54.

- Caughey, John (1975), p. 17

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 197–202.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 63. Holliday notes these luckiest prospectors were recovering, in short amounts of time, gold worth in excess of $1 million when valued at the dollars of today.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 28.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 57–61.

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 53–61.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 53–56.

- Johnson, Susan (2001), p. 59.

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 61–64.

- Magagnini, Stephen (January 18, 1998)"Chinese transformed 'Gold Mountain'", The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 93–103.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 57–61. Other estimates range from 70,000 to 90,000 arrivals during 1849 (ibid. p. 57).

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 25.

- "Exploration and Settlement – John Bull and Uncle Sam: Four Centuries of British-American Relations – Exhibitions (Library of Congress)". loc.gov.

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 193–194.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 62.

- "The Oregon Trail". isu.edu. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008.

- Neary, J. (2015), pp. 226-248

- Freguli, Carolyn. (eds.) (2008), pp.8–9.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 5. Another estimate is 2,500 forty-niners of African ancestry.

- African Americans who were slaves and came to California during the Gold Rush could gain their freedom. One of the miners was African American Edmond Edward Wysinger (1816–1891), see also Moses Rodgers (1835–1900)

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 67–69.

- Faragher, John (2006), p. 411

- "The Gold Rush". The American Experience. 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- "Men : Women in Early San Francisco". FoundSF. August 26, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "Key Points in Black History and the Gold Rush – Instructional Materials (CA Dept of Education)". Cde.ca.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- Moynihan, Ruth B., Armitage, Susan, and Dichamp, Christiane Fischer (eds.) (1990). p. 3-8.

- Levy, Joann (1992). p. xxii, p. 92.

- By one account, in late 1850, the population of California was over 110,000, not including the Californios or the California Indians. The surviving U.S. census counts in California add up to 92,600, not including the lost censuses of San Francisco (the largest city in California at that time), Contra Costa county and Santa Clara County. The women who came to California in the early years were a distinct minority, consisting of less than 10% of the population.

- Young, Otis (1970), pp. 111–112.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 115-123.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 235.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 123-125.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 127. There were fewer than 1,000 U.S. soldiers in California at the beginning of the Gold Rush.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 27.

- The federal law in place at the time of the California Gold Rush was the Preemption Act of 1841, which allowed "squatters" to improve federal land, then buy it from the government after 14 months.

- Paul, Rodman (1947), pp. 211-213

- Clay, Karen and Wright, Gavin. (2005), pp. 155–183.

- Clappe, Louise (1922), pp. 207-221. "Dame Shirley" was the name adopted by Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe as she wrote a series of letters to her family describing in detail her life in the Feather River goldfields. The letters were originally published in 1854–1855 by The Pioneer magazine.

- The rules of mining claims adopted by the forty-niners spread with each new mining rush throughout the western United States. The U.S. Congress finally legalized the practice in the "Chaffee laws" of 1866 and the "placer law" of 1870. Lindley, Curtis H. (1914) A Treatise on the American Law Relating to Mines and Mineral Lands, San Francisco: Bancroft-Whitney, p.89–92. Karen Clay and Gavin Wright, "Order Without Law? Property Rights During the California Gold Rush." Explorations in Economic History 2005 42(2): 155–183. See also John F. Burns, and Richard J. Orsi, eds; Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California University of California Press, 2003

- Information Sharing During the Klondike Gold Rush, p. 13–14. Douglas W. Allen, Simon Fraser University

- Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 169–173.

- Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 94–100.

- Young, Otis (1970), pp. 106–108.

- Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 105–110.

- Young, Otis (1970), pp. 108–110.

- Brands, H. W. (2002), pp. 198–200.

- "goldrushtrail.net". Archived from the original on May 14, 2006.

- Bancroft, Hubert (1884), pp. 87-88.

- Young, Otis (1970), pp. 110–111.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 90.

- The Troy weight system is traditionally used to measure precious metals, not the more familiar avoirdupois weight system. The term "ounces" used in this article to refer to gold typically refers to troy ounces. There are some historical uses where, because of the age of the use, the intention is ambiguous.

- Hayes, Garry "Mining History and Geology of the California Gold Rush", Modesto Junior College (accessed September 20, 2018).

- Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 89.

- Use of volumes of water in large-scale gold-mining dates at least to the time of the Roman Empire. (See Roman-era gold mines in Spain.) Roman engineers built extensive aqueducts and reservoirs above gold-bearing areas, and released the stored water in a flood so as to remove over-burden and expose gold-bearing bedrock, a process known as hushing. The bedrock was then attacked using fire and mechanical means, and volumes of water were used again to remove debris, and to process the resulting ore. Examples of this Roman mining technology may be found at Las Médulas in Spain and Dolaucothi in South Wales. The gold recovered using these methods was used to finance the expansion of the Roman Empire. Hushing was also used in lead and tin mining in Northern Britain and Cornwall. There is, however, no evidence of the earlier use of hoses, nozzles and continuous jets of water in the manner developed in California during the Gold Rush.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 32-36.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 116-121.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 199.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 36-39.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 39-43.

- Charles N. Alpers; Michael P. Hunerlach; Jason T. May; Roger L. Hothem. "Mercury Contamination from Historical Gold Mining in California". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved February 26, 2008.

- Hausel, Dan. "California – Gold, Geology & Prospecting". Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- Clay, Karen; Jones, Randall (2008). "Migrating to Riches? Evidence from the California Gold Rush". Journal of Economic History. 68 (4): 997–1027. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.163.572. doi:10.1017/S002205070800079X.

- Rohrbough, Malcolm (1998)

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 69-70.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 63.

- Zerbe, R. O.; Anderson, C. L. (2001). "Culture and fairness in the development of institutions in the California gold fields". Journal of Economic History. 61 (1): 114–143. doi:10.1017/S0022050701025062. JSTOR 2697857.

- Sears, Clare (2014), p. 68. "In 1852 the California state legislature targeted Chinese residents for a 'foreign miners' tax [...]"

- Levi's jeans were not invented until the 1870s. Lynn Downey, Levi Strauss & Co. (2007)

- James Lick made a fortune running a hotel and engaging in land speculation in San Francisco. Lick's fortune was used to build Lick Observatory.

- Four particularly successful Gold Rush era merchants were Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, Sacramento area businessmen (later known as the Big Four) who financed the western leg of the First Transcontinental Railroad, and became very wealthy as a result.

- Johnson, Susan (2001), pp. 164-168.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 52-68, pp. 193-197

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 212-214.

- Young, Otis (1970), p. 109.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 256-259.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 90.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 193-97, pp. 214-215.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 214.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 212.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 226-227.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 50. Other estimates are that there were 7,000–13,000 non-Native Americans in California before January 1848. See Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 26, p. 51.

- Historians have reflected on the Gold Rush and its effect on California. Historian Kevin Starr stated that for all its problems and benefits, the Gold Rush established the "founding patterns, the DNA code, of American California", and quotes from The Annals of San Francisco in 1855 that the Gold Rush advanced California into a "rapid, monstrous maturity". See Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 80 and Starr, Kevin (1973), p. 110.

- Davis, Joseph; Weidenmier, Marc D. (2017). "America's First Great Moderation" (PDF). The Journal of Economic History. 77 (4): 1116–1143. doi:10.1017/S002205071700081X. ISSN 0022-0507.

- Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 91-93.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 243-248. By 1860, California had over 200 flour mills, and was exporting wheat and flour around the world. Ibid. at 278–280.

- Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 110-111.

- Starr, Kevin (1973), pp. 69-75.

- Caughey, 1975, p. 192

- Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1870, U.S. Bureau of the Census

- "Monthly Record of Current Events". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 10 (58): 543. March 1855.

From California we have intelligence to January 16. The railroad across the Isthmus of Panama is completed, and trains passed.. for the first time on the 28th of January.

- S.S. Central America information Archived November 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; Final voyage of the S.S. Central America. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 192–196.

- Another notable ship wreck was the steamship Winfield Scott, bound to Panama from San Francisco, which crashed into Anacapa Island off the Southern California coast in December 1853. All hands and passengers were saved, along with the cargo of gold, but the ship was a total loss.

- "Focus On the West". apstudynotes.org.

- Castillo, Edward D. (1998). "California Indian History". Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- "Native History: California Gold Rush Begins, Devastates Native Population". Indian Country Today Media Network.com. January 24, 2014. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "Native History: California Gold Rush Begins, Devastates Native Population". Indian Country Today Media Network.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- While the Bloody Island Massacre occurred during this time period, it did not occur in the Gold Rush era mining districts.

- "Trinity County California". visittrinity.com. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- Madley, Benjamin (2016), p. 11, p. 351

- Thornton 1987, pp. 107–109.

- "Minorities During the Gold Rush". California Secretary of State. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- Norton, Jack (1979). pp. 70-73

- Smith, Chuck (1999). "Indians of California – American Period (Anthropology Class 6)". Cabrillo College. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018.

- Lindsay, Brenden (2012), p. 231.

- Lindsay, Brenden (2012). p. 148.

- Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 56–79.

- Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 84-87.

- Cossley-Batt, Jill (1928), ch. 16: "California Banditti". Joaquin Murrieta was a famous Mexican bandit during the Gold Rush of the 1850s.

- (in Spanish) Villalobos, Sergio; Silva, Osvaldo; Silva, Fernando and Estelle, Patricio. 1974. Historia De Chile. Editorial Universitaria, Chile. p 481-485.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), p. 286.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 287-289.

- Younger, R. M. 'Wondrous Gold' in Australia and the Australians: A New Concise History, Rigby, Sydney, 1970

- Narron, James; Morgan, Don (August 7, 2015). "Crisis Chronicles–The California Gold Rush and the Gold Standard". New York Fed. Liberty Street Economics. New York, NY: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

The gold rush constituted a positive monetary supply shock because the United States was on the gold standard at the time. The nation had switched from a bimetallic (gold and silver) standard to a de facto gold standard in 1834. Under the latter, the U.S. government stood ready to buy gold for $20.67 per ounce, a parity that prevailed until 1933. That commitment anchored prices, but the large gold discovery functioned like a monetary easing by a central bank, with more gold chasing the same amount of goods and services. The increase in spending ultimately led to higher prices because nothing real had changed except the availability of a shiny yellow metal.

- Rawls, James J. (1999), pp. 278-279.

- Historians James Rawls and Walton Bean have postulated that were it not for the discovery of gold, Oregon might have been granted statehood ahead of California, and therefore the first "Pacific Railroad might have been built to that state." See Rawls, James, J., and Walton Bean (2003), p. 112.

- Starr, Kevin (1973)

- Brands, H. W. (2002), p. 442.

- A perception of lawlessness also was connected with California. See Burchell, Robert A. (1974). "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875". California Historical Quarterly. 53 (2): 115–30. doi:10.2307/25157500. JSTOR 25157500. (stories about Gold Rush lawlessness deterred some immigration for two decades).

- Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 110. "[A]griculture dominated the post-Gold Rush sequence of development, employing more people than mining by 1869 ... and surpassing mining in 1879 as the leading element of the California economy."

- See, e.g., Signal Hill, California, Bakersfield, California; Los Angeles, California

- 20th Century-Fox, MGM, Paramount, RKO, Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, and United Artists are among the most recognized entertainment industry names centered in California; see also Film studio

- Douglas Aircraft, Lockheed Aircraft, Hughes Aircraft, North American Aviation, Convair, and Northrop were among the complex of companies in the aerospace industry which flourished in California during and after World War II.

- Gaither, Chris; Chmielewski, Dawn C (October 10, 2006). "Google Bets Big on Videos". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- Gold Rush images on the state seal include a forty-niner digging with a pick and shovel, a pan for panning gold, and a "long-tom." In addition, the ships on the water suggest the sailing ships filling the Sacramento River and San Francisco Bay during the Gold Rush era.

- "Economic Development History of State Route 99 in California". Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

In the 1960s, green and white CA-99 signs that resemble miners' spades replaced the black and white U.S. 99 shields

- Papoulias, Alexander (January 4, 2008). "Car Sales Curbed Along El Camino". Palo Alto Weekly. Office of California State Senator Leland Yee. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

State routes can be identified by the green State Highway Route shield, which is in the shape of a spade in honor of the California Gold Rush, and bears the route's number

- "Your guide to the Mother Lode: Complete map of historic Hwy 49". historichwy49.com. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- Watson, Matthew (2005) looks at Bret Harte's notion of Western partnership in such California gold rush stories as "The Luck of Roaring Camp" (1868), "Tennessee's Partner" (1869), and "Miggles" (1869). While critics have long recognized Harte's interest in gender constructs, Harte's depictions of Western partnerships also explore changing dynamics of economic relationships and gendered relationships through terms of contract, mutual support, and the bonds of labor.

References

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884). History of California: 1848–1859. San Francisco: The History Company.

- Blakely, Jim; Barnette, Karen (July 1985). Historical Overview: Los Padres National Forest (PDF).

- Boyd, Nan Alamilla (2003). Wide-Open Town: A History of Queery San Francisco to 1965. University of California Press.

- Brands, H. W. (2002). The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-50216-8.

- Caughey, John Walton (1975). The California Gold Rush. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02763-3.

- Clappe, Louise Amelia Knapp Smith (1922). The Shirley Letters from the California Mines, 1851–1852. San Francisco: T.C. Russell.

- Clay, Karen; Gavin Wright (April 2005). "Order Without Law? Property Rights During the California Gold Rush" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 42 (2): 155–183. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2004.05.003.

- Cossley-Batt, Jill L. (1928). The Last of the California Rangers. New York and London: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

- Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail: The Hudson's Bay Company Route to California. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-016980-7.

- Faragher, John Mack (2006). Out of Many: A History of the American People (5th ed.). Pearson. p. 411.

- Gaither, Chris; Chmielewski, Dawn C. (October 10, 2006). "Google Bets Big on Videos" (PDF). Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2006.

- Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The Destruction of California Indians. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7262-0.

- Hill, Mary (1999). Gold: The California Story. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21547-4.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for Riches: Gold Fever and the Making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21401-9.

- Johnson, Susan Lee (2001). Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32099-2.

- Levy, JoAnn (1990). They Saw the Elephant: Women in the California Gold Rush. Hamden, CT: Archon Books. ISBN 0-208-02273-2.

- Lindsay, Brenden C. (2012). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846–1873. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803224803.

- Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300181364.

- Miller, Joaquin (1874). Life Amongst the Modocs. Hartford, CT: American Publishing Company.

- Neary, J.; Robbins, Hollis (2015). "11: African American Literature of the Gold Rush". Mapping Regions in Early American Writing. University of Georgia Press. pp. 226–248. ISBN 978-0-8203-4823-0.

- Norton, Jack (1979). Genocide in Northwestern California: When Our Worlds Cried. San Francisco: Indian Historian Press.

- Paul, Rodman W. (1969) [1947]. California Gold: The Beginning of Mining in the Far West. Bison: University of Nebraska Press.

- Rohrbough, Malcolm J. (1998). Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21659-4.

- Moynihan, Ruth B.; Armitage, Susan; Dichamp, Christiane Fischer, eds. (1990). So Much to be Done: Women Settlers on the Mining and Ranching Frontier (2nd ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8248-3.

- Rawls, James, J.; Bean, Walton (2003). California: An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-255255-3.

- Rawls, James J.; Orsi, Richard J., eds. (1999). A Golden State: Mining and Economic Development in Gold Rush California. California History Sesquicentennial, 2. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21771-3.

- Sears, Clare (2014). Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco. Duke University Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8223-5754-4.

- Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California Dream: 1850–1915. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504233-7.

- Starr, Kevin (2005). California: A History. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-679-64240-4.

- Starr, Kevin and Richard J. Orsi (eds.) (2000). Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22496-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Thornton, Russell (1987). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2074-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watson, Matthew A. (2005). "The Argonauts of '49: Class, Gender, and Partnership in Bret Harte's West". Western American Literature. 40 (1): 33–53. doi:10.1353/wal.2005.0076.

- Wells, Harry L. (1881). History of Siskiyou County, California. Oakland, California: D.J. Stewart & Co.

- Young, Otis E. (1970). Western Mining. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1352-4.</ref>

Further reading

- Burchell, Robert A. (Summer 1974). "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875". California Historical Quarterly. 53 (3): 115–130. doi:10.2307/25157500. ISSN 0097-6059. JSTOR 25157500.

- Burns, John F. and Richard J. Orsi (eds.) (2003). Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23413-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Drager, K.; C. Fracchia (1997). The Golden Dream: California from Gold Rush to Statehood. Portland, Oregon: Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-55868-312-9.

- Durham, Walter T. (1997). Volunteer Forty-Niners: Tennesseans and the California Gold Rush. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 9780585170930. OCLC 44959444.

- Dwyer, Richard A.; Richard E. Lingenfelter; David Cohen (1964). The Songs of the Gold Rush. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Eifler, Mark A. (2002). Gold Rush Capitalists: Greed and Growth in Sacramento. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2822-9.

- Hart, Eugene (2003). A Guide to the California Gold Rush. Merced: Freewheel Publications. ISBN 978-0-9634197-2-9.

- Helper, Hinton Rowan (1855). The Land of Gold: Reality Versus Fiction. Baltimore: H. Taylor.

- Holliday, J. S.; Swain, William (2002) [1981]. The World Rushed in: The California Gold Rush Experience. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3464-2.

- Hurtado, Albert L. (2006). John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3772-8.

- Klare, Normand E. (2005). The Final Voyage of the SS Central America 1857. Ashland, Oregon: Klare Taylor Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9764403-0-7.

- Knorr, Lawrence (2008). A Pennsylvania Mennonite and the California Gold Rush. Camp Hill: Sunbury Press. ISBN 978-0-9760925-8-2.

- Lienhard, Heinrich. "Wenn Du absolut nach Amerika willst, so gehe in Gottesnamen!", Erinnerungen an den California Trail, John A. Sutter und den Goldrausch 1846–1849. Herausgegeben von [edited by] Christa Landert, mit einem Vorwort von [foreword by] Leo Schelbert. Zürich: Limmat Verlag, 2010, 2011. ISBN 978-3-85791-504-8

- Owens, Kenneth N. (ed.) (2002). Riches for All: The California Gold Rush and the World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8617-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Haun Collection Archive". Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- Roberts, Brian (2000). American Alchemy: The California Gold Rush and Middle-class Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4856-2.

- Rohrbough, Malcolm J. (1998). Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21659-4. online edition

- Stiles, T.J. (2009). The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt. Knopf. ISBN 9780375415425.

- Watson, Matthew A. (2005). "The Argonauts of '49: Class, Gender, and Partnership in Bret Harte's West". Western American Literature. 40 (1): 33–53. ISSN 0043-3462.

- Witschi, N. S. (2004). "Bret Harte." Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Ed. Jay Parini. New York: Oxford University Press. 154–157.

- Witschi, N.S. (2002). Traces of Gold: California's Natural Resources and the Claim to Realism in Western American Literature. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1117-9.

Maps

- Ord, Edward Otho Cresap, Topographical sketch of the gold & quicksilver district of California, 1848. from loc.gov accessed October 4, 2018.

- Lawson's Map from Actual Survey of the Gold, Silver & Quicksilver Regions of Upper California Exhibiting the Mines, Diggings, Roads, Paths, Houses, Mills, Missions &c. &c by J.T. Lawson, Esq. Cala. . . . New York, 1849. from raremaps.com accessed October 4, 2018. Lawson's map of the Gold Regions is the first map to accurately depict California's Gold Regions. Issued in January 1849, at the beginning of the California Gold Rush, Lawson's map was produced specifically for prospectors and miners.

- A Correct Map of the Bay of San Francisco and the Gold Region from actual Survey June 20th. 1849 for J.J. Jarves. Embracing all the New Towns, Ranchos, Roads, Dry and Wet Diggings, with their several distances from each other, James Munroe & Co. of Boston, 1849 from raremaps.com accessed October 4, 2018. One of the earliest maps of the gold region made from personal observation, Jarves' map states on it that it was the result of a survey of the diggings made for him on June 20, 1849.

- George Derby, Sketch of General Riley's Route Through the Mining Districts July and Aug., J. McH. Hollingsworth, New York, 1849 from raremaps.com accessed October 4, 2018.

- The Sacramento Valley from The American River to Butte Creek, Surveyed & Drawn by Order of Gen.l Riley ... by Lt. George H. Derby,... September & October 1849, Washington, 1849 from raremaps.com accessed October 4, 2018. Map by Lt. George H. Derby, from Tyson's Information in Relation to the Geology and Topography of California.

- Jackson, William A., Map of the mining district of California, Lambert & Lane's Lith., 1850. from loc.gov accessed October 4, 2018.

- Map of the Gold Region of California taken from a recent survey By Robert H. Ellis 1850 (with early manuscript annotations), George F. Nesbitt, Lith., New York, 1850 from raremaps.com accessed October 4, 2018. A later 1850 map showing the growing settlement in the goldfields and in that vicinity of the state.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to California Gold Rush. |

- California Gold Rush at Curlie

- California Gold Rush chronology at The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- Gold at the website of United States Geological Survey

- Gold Country Museum in Placer County, California

- "California as I Saw It:" First-Person Narratives of California's Early Years, 1849–1900 Library of Congress American Memory Project

- University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library

- The University of California, Calisphere, 1848–1865: The Gold Rush Era

- California State Library, "California As We Saw It": Exploring the California Gold Rush, online exhibit

- Map of North America during the California Gold Rush at omniatlas.com

- Lewis B. Rush diary, diary of a gold rush miner, MSS SC 161 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Gold Rush Collection. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.