East Asian cultural sphere

The East Asian cultural sphere, or the Sinosphere (additionally known as the Sinic/Sinitic world, the Confucian world or the Taoist world), refers to countries in East and Southeast Asia which were historically influenced by Chinese culture. The area has also been known as the Chinese cultural sphere, although this title is often utilised in particular reference to the Sinophone community, defined as including any place or neighbourhood inhabited by a significant number of people who speak varieties of Chinese; the terms "East Asian cultural sphere" and "Chinese character (Hànzì) cultural sphere" are used interchangeably with "Sinosphere", but have different connotations depending on the context and point of view of the writers. The East Asian cultural sphere is comparable in this regard to the Arab world, Western world, Latin world, Greater India, Greater Iran and Turkic world, among others.

| East Asian cultural sphere | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 東亞文化圈 漢字文化圈 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 东亚文化圈 汉字文化圈 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Vùng văn hóa Đông Á Vùng văn hóa chữ Hán Đông Á văn hóa quyển Hán tự văn hóa quyển | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 塳文化東亞 塳文化𡨸漢 東亞文化圈 漢字文化圈 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 동아문화권 한자문화권 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 東亞文化圈 漢字文化圈 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 東亜文化圏 漢字文化圏 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | とうあぶんかけん かんじぶんかけん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

Cultural common denominators in the Sinosphere include the philosophies and religions known in the West as Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, along with important political and social institutions, legal and ritual practices, military and medical ideas and other cultural components in areas such as literature, art and architecture. The core regions of the East Asian cultural sphere included from antiquity to present are generally Greater China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam.

One facilitator of cultural exchange in the Sinosphere was “literary Sinitic” or Classical Chinese. This logographic script was invented in China several thousand years ago and became a commonly utilised literary lingua franca, allowing for the transmission of medical, scientific, literary, political, religious and cultural texts throughout the region. For more than a thousand years, until the early 20th century, the aristocracy and academics of the Sinosphere communicated in writing primarily using classical Chinese, alongside local written scripts such as Katakana and Hangul, which were utilised within their respective countries.[1]

Cultural exchange in the Sinosphere flowed in multiple directions; recent studies concerning the utilisation of literary Sinitic in East Asia have demonstrated that as well as bringing new cultural influences to Japan, Korea and Vietnam, both the language and the concepts transmitted to these environments via the literary Sinitic were transformed by them. [2] [3] The other countries of East Asia did not simply receive Chinese culture; they also actively participated in an ongoing and creative process of cultural interaction, exchange and reinvention. [4]

The historical force of Chinese traditions and cultural practices has extended beyond the East Asian cultural sphere to varying degrees and at various times. This can be seen in the establishment of overseas Chinese communities dating back to the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries in Southeast Asian nations such as Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos and the Philippines. Chinese architecture has also influenced the architecture of other Asian nations, including Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and the Philippines.[5][6][7][8][9] More recently, new waves of Mainland Chinese migrants have led to the emergence of large modern-day ethnic Chinese communities in a number of major cities in various parts of Southeast Asia and South Asia, notably Sihanoukville in Cambodia and Mandalay in Myanmar.[10][11]

Terminology

China has been regarded as one of the centres of civilisation, with the emergent cultures that arose from the migration of original Han settlers from the Yellow River generally remaining regarded as the starting point of the East Asian world. Nowadays, its population is approximately 1.43 billion (see Demographics of China).

The Japanese historian Nishijima Sadao (1919–1998), professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, originally coined the term Tōa bunka-ken (東亜文化圏, 'Tao Cultural Area'; later borrowed into Chinese). He conceived of a Chinese or East Asian cultural sphere distinct from the cultures of the west. According to Nishijima, this cultural sphere shared the philosophy of Confucianism, the religion of Buddhism, and similar political and social structures. His cultural sphere includes China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, stretching from areas between Mongolia and the Himalayas.[12]

Etymology of 'Sinosphere'

The term Sinosphere is sometimes used as a synonym for the East Asian cultural sphere, with the etymology of Sinosphere derived from Sino- ('China, Chinese") and -sphere in the sense of 'sphere of influence, area influenced by a country'. (cf. Sinophone.)

As cognates of each other, the "CJKV" languages—Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese—translate the English -sphere as:[13][14]

- Chinese: quān (圈, 'circle, ring, corral, pen')

- Japanese: ken (圏けん, 'sphere, circle, range, radius')

- Korean: gwon (권)

- Vietnamese: quyển

Victor H. Mair discussed the origins of these "culture sphere" terms.[15] The Chinese wénhuà quān (文化圈) dates back to a 1941 translation for the German term Kulturkreis, (''culture circle/field"), which the Austrian ethnologists Fritz Graebner and Wilhelm Schmidt proposed. Japanese historian Nishijima Sadao coined the expressions Kanji bunka ken (漢字文化圏, "Chinese-character culture sphere") and Chuka bunka ken (中華文化圏, "Chinese culture sphere"), which China later re-borrowed as loanwords. Nishijima devised these Sinitic "cultural spheres" within his Theory of an East Asian World (東アジア世界論, Higashi Ajia sekai-ron).

Chinese-English dictionaries provide similar translations of this keyword wénhuà quān (文化圈) as "the intellectual or literary circles" (Liang Shiqiu 1975) and "literary, educational circles" (Lin Yutang 1972).

The Sinosphere may be taken to be synonymous to Ancient China and its descendant civilisations as well as the "Far Eastern civilisations" (the Mainland and the Japanese ones). In the 1930s in A Study of History, the Sinosphere along with the Western, Islamic, Eastern Orthodox, Indic, etc. civilisations is presented as among the major "units of study."[16]

Comparisons with the West

The British historian Arnold J. Toynbee listed the Far Eastern civilisation as one of the main civilisations outlined in his book, A Study of History. He included Japan and Korea in his definition of "Far Eastern civilisation" and proposed that they grew out of the "Sinic civilisation" that originated in the Yellow River basin.[17] Toynbee compared the relationship between the Sinic and Far Eastern civilisation with that of the Hellenic and Western civilisations, which had an "apparentation-affiliation."[18]

The American Sinologist and historian Edwin O. Reischauer also grouped China, Korea, and Japan into a cultural sphere that he called the Sinic world, a group of centralised states that share a Confucian ethical philosophy. Reischauer states that this culture originated in Northern China, comparing the relationship between Northern China and East Asia to that of Greco-Roman civilisation and Europe. The elites of East Asia were tied together through a common written language based on Chinese characters, much in the way that Latin had functioned in Europe.[19]

The American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington considered the Sinic world as one of many civilisations in his book The Clash of civilisations. He notes that "all scholars recognize the existence of either a single distinct Chinese civilisation dating back to at least 1500 B.C. and perhaps a thousand years earlier, or of two Chinese civilisations one succeeding the other in the early centuries of the Christian epoch."[20] Huntington's Sinic civilisation includes China, North Korea, South Korea, Mongolia, Vietnam and Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.[21] Of the many civilisations that Huntington discusses, the Sinic world is the only one that is based on a cultural, rather than religious, identity.[22] Huntington's theory was that in a post-Cold War world, humanity "[identifies] with cultural groups: tribes, ethnic groups, religious communities [and] at the broadest level, civilisations."[23][24]

East-Asian culture

Arts

Architecture

Countries from the East Asian cultural sphere share a common architectural style stemming from the architecture of ancient China.[25]

Calligraphy

Cinema

Martial Arts

Music

Chinese musical instruments, such as erhu, have influenced those of Indonesia, Korea, Japan and Vietnam.[26]

Cuisine

The cuisine of East Asia shares many of the same ingredients and techniques. Chopsticks are used as an eating utensil in all of the core East Asian countries.[27] The use of soy sauce, which is made from fermenting soybeans, is also widespread in the region.

Rice (米飯, mǐfàn) is a main staple food in all of East Asia and is a major focus of food security.[28] Moreover, in East Asian countries, the word for 'cooked rice' (simplified Chinese: 饭; traditional Chinese: 飯; pinyin: fàn) can embody the meaning of food in general.[27]

Popular terms associated with East Asian cuisine include kimchi (泡菜, pàocài), sushi (壽司, shòusī), hot pot (火鍋, huǒguō), tea (茶, chá), dumplings (餃子, jiǎozi), dimsum (點心, diǎnxīn), noodles (麵, miàn) / ramen, as well as phở, sashimi, wasabi, udon, among others.[29]

Traditions

Fashion[26]

Lion Dance

The Lion Dance is a form of traditional dance in Chinese culture and other culturally East Asian countries in which performers mimic a lion's movements in a lion costume to bring good luck and fortune. Aside from China, versions of the lion dance are found in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Tibet, and Taiwan. Lion Dances are usually performed during New Year, religious and cultural celebrations.

New Year

Greater China, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam traditionally observe the same Lunar New Year. However, Japan has moved its New Year to fit the Western New Year since the Meiji Restoration.

Philosophy and religion

The Art of War, Tao Te Ching, Analects are classic Chinese texts that have been influential in East Asian history.

Taoism

The countries of China, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam have been influenced by Taoism. It is also called as Onmyōdō in Japan.

Shintoism

Shintoism is the ethnic religion of Japan. Shinto means "Way of the Gods". Shinto practitioners commonly affirm tradition, family, nature, cleanliness and ritual observation as core values.[30]

Ritual cleanliness is a central part of Shinto life.[31] Shrines have a significant in Shinto, being places for the veneration of the kami (gods or spirits).[32] "Folk", or "popular", Shinto features an emphasis on shamanism, particularly divination, spirit possession and faith healing. "Sect" Shinto is a diverse group including mountain-worshippers and Confucian Shinto schools.[33]

Buddhism

The countries of China, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam share a history of Mahayana Buddhism. It spread from India via the Silk Road through Pakistan, Xinjiang, east as well as through SEA, Vietnam, then north through Guangzhou and Fujian. From China, it proliferated to Korea and Japan, especially during the Tang dynasty (see Kukai). It could have also re-spread from China south to Vietnam. East Asia is now home to the largest Buddhist population in the world at around 200-400 million (see Buddhism by country; the top five are China, Thailand, Myanmar, Japan, Vietnam—three countries within the East Asian Cultural Sphere).

Confucianism

The countries of China, Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam share a Confucian philosophical worldview.[19] Confucianism is a humanistic[34] philosophy that believes that human beings are teachable, improvable and perfectible through personal and communal endeavour especially including self-cultivation and self-creation. Confucianism focuses on the cultivation of virtue and maintenance of ethics, the most basic of which are rén (仁), yì (义/義), and lǐ (礼/禮).[35] Ren is an obligation of altruism and humaneness for other individuals, yi is the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition to do good, and li is a system of norms and propriety that determines how a person should properly act in everyday life.[35]

Neo-Confucianism

Mid-Imperial Chinese philosophy is primarily defined by the development of Neo-Confucianism. During the Tang dynasty, Buddhism from Nepal also became a prominent philosophical and religious discipline. Neo-Confucianism has its origins in the Tang dynasty; the Confucianist scholar Han Yu is seen as a forebear of the Neo-Confucianists of the Song dynasty.[36] The Song dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi is seen as the first true "pioneer" of Neo-Confucianism, using Daoist metaphysics as a framework for his ethical philosophy.[37]

Elsewhere in East Asia, Japanese philosophy began to develop as indigenous Shinto beliefs fused with Buddhism, Confucianism and other schools of Chinese philosophy. Similar to Japan, in Korean philosophy elements of Shamanism were integrated into the Neo-Confucianism imported from China. In Vietnam, neo-Confucianism was developed into Vietnamese own Tam giáo as well, along with indigenous Vietnamese beliefs and Mahayana Buddhism.

Other religions

Though not commonly identified with that of East Asia, the following religions have been influential in its history:

- Hinduism, see Hinduism in Vietnam, Hinduism in China

- Islam, see Xinjiang, Muslims in China, Islam in Hong Kong, Islam in Japan, Islam in Korea, Islam in Vietnam.

- Christianity, one of the most popular religions in Hong Kong, Korea, etc.

Language

Historical linguistics

Various languages are thought to have originated in East Asia and have various degrees of influence on each other. These include:

- Sino-Tibetan: Spoken mainly in China, Myanmar, Northeast India and parts of Nepal. Major Sino-Tibetan languages include the varieties of Chinese, the Tibetic languages and Burmese. They are thought to have originated around the Yellow River north of the Yangzi.[38][39]

- Austronesian: Spoken mainly in Taiwan, Indonesia, Madagascar, and the Pacific Islands. Major Austronesian languages include Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Javanese, and Filipino (Tagalog).

- Austroasiatic: Spoken mainly in Vietnam and Cambodia. Major Austroasiatic languages include Vietnamese and Khmer.

- Kra-Dai: Spoken mainly in Thailand, Laos, and parts of Southern China. Major Kra-Dai languages include Thai and Lao.

- Mongolic: Spoken mainly in Mongolia and China. Major Mongolian languages include Mongolian, Monguor, Dongxiang and Buryat.

- Tungusic: Spoken mainly in Siberia and China. Major Tungusic languages include Evenki, Manchu, and Xibe.

- Koreanic: Spoken mainly in Korea. Major Korean languages include Korean, and Jeju.

- Japonic: Spoken mainly in Japan. Major Japonic languages include Japanese, Ryukyuan and Hachijo

- Ainu language: Spoken mainly in Japan and considered an isolate.

The core Languages of the East Asian Cultural Sphere generally include the varieties of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. All of these languages have a well-documented history of having historically used Chinese characters, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese all having roughly 60% of their vocabulary stemming from Chinese.[40][41][42] There is a small set of minor languages that are comparable to the core East Asian languages such as Zhuang and Hmong-Mien. They are often overlooked since neither have their own country or heavily export their culture, but Zhuang has been written in hanzi inspired characters called Sawndip for over 1000 years. Hmong, while having supposedly lacked a writing system until modern history, is also suggested to have a similar percentage of Chinese loans to the core CJKV languages as well.[43]

While other languages have been impacted by the Sinosphere such as the Thai with its Thai numeral system and Mongolian with its historical use of hanzi: the amount of Chinese vocabulary overall is not nearly as expansive in these languages as the core CJKV, or even Zhuang and Hmong.

Various hypotheses are trying to unify various subsets of the above languages, including the Sino-Austronesian and Austric language groupings. An overview of these various language groups is discussed in Jared Diamond's Germs, Guns, and Steel, among other places.

Writing systems

East Asia is quite diverse in writing systems, from the Brahmic, inspired abugidas of SEA, the logographic hanzi of China, the syllabaries of Japan, and various alphabets and abjads used in Korea (Hangul), Mongolia (Cyrillic), Vietnam (Latin), Indonesia (Latin), etc.

| Writing system | Regions |

|---|---|

| Logograms 漢字 | China, Hong Kong, Macau, Japan, Korea, Vietnam*, Singapore, Taiwan |

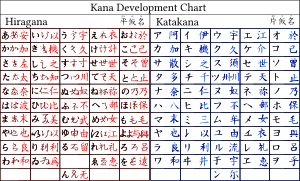

| Syllabary (かな, kana) | Japan |

| Alphabet (한글, hangul) | Korea |

| Abugidas (spread from India) | China (Tibet), Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Malays* |

| Alphabet (Latin) | Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Brunei, East Timor |

| Alphabet (Cyrillic) | Mongolia (though there is movement to switch back to Mongolian script)[44] |

| Alphabet (Mongolian) | Mongolia*, China (Inner Mongolia) |

| Abjad | China (Xinjiang), Malays*, Brunei |

| * unofficial usage. | |

Characters influences

Hanzi (漢字 or 汉字) is considered the common culture that unifies the languages and cultures of many East Asian nations. Historically, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam have used Chinese characters. Today, they are mainly used in China, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore albeit in different forms.

Mainland China and Singapore use simplified characters, whereas Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau use traditional.

Japan still uses kanji but has also invented kana, believed to be inspired by the abugida scripts of southern Asia.

Korea used to write in hanja but has invented an alphabetic system called hangul (also inspired by Chinese and phags-pa during the Mongol Empire) that is nowadays the majority script. However, hanja is a required subject in South Korea. Names are also written in hanja. Hanja is also studied and used in academia, newspapers, and law; areas where a lot of scholarly terms and Sino-Korean loanwords are used and necessary to distinguish between otherwise ambiguous homonyms.

Vietnam used to write in chữ Hán or Classical Chinese. Since the 8th century they began inventing many of their own chữ Nôm. Since French colonization, they have switched to using a modified version of the Latin alphabet called chữ Quốc ngữ. However, Chinese characters still hold a special place in the cultures as their history and literature have been greatly influenced by Chinese characters. In Vietnam (and North Korea), hanzi can be seen in temples, cemeteries, and monuments today, as well as serving as decorative motifs in art and design. And there are movements to restore Hán Nôm in Vietnam. (Also see History of writing in Vietnam.)

Zhuang are similar to the Vietnamese in that they used to write in Sawgun (Chinese characters) and have invented many of their characters called Sawndip (Immature characters or native characters). Sawndip is still used informally and in traditional settings, but in 1957, the People's Republic of China introduced an alphabetical script for the language, which is what it officially promotes.[45]

Literature

East Asian literary culture was based on the use of Literary Chinese, which became the medium of scholarship and government across the region. Although each of these countries developed vernacular writing systems and used them for popular literature, they continued to use Chinese for all formal writing until it was swept away by rising nationalism around the end of the 19th century.[46]

Throughout East Asia, Literary Chinese was the language of administration and scholarship. Although Vietnam, Korea, and Japan each developed writing systems for their languages, these were limited to popular literature. Chinese remained the medium of formal writing until it was displaced by vernacular writing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[47] Though they did not use Chinese for spoken communication, each country had its tradition of reading texts aloud, the so-called Sino-Xenic pronunciations, which provide clues to the pronunciation of Middle Chinese. Chinese words with these pronunciations were also borrowed extensively into the local vernaculars, and today comprise over half their vocabularies.[48]

Books in Literary Chinese were widely distributed. By the 7th century and possibly earlier, woodblock printing had been developed in China. At first, it was used only to copy the Buddhist scriptures, but later secular works were also printed. By the 13th century, metal movable type was used by government printers in Korea but seems to have not been extensively used in China, Vietnam, or Japan. At the same time manuscript reproduction remained important until the late 19th century.[49]

Japan's textual scholarship had Chinese origin which made Japan one of the birthplaces of Sinology.[50]

Geopolitics and international relations

Some analysts say that Australia and New Zealand are increasingly under Asian influence both culturally and economically due to its proximity.[51] In 2019, Italy became the first G7 country to sign a BRI memorandum with China, much to the dismay of the United States.[52]

Economy and trade

The business cultures of Sinosphere countries in some ways are heavily influenced by Confucianism.

Important in China is the social concept of 關係 or guanxi. This has influenced the societies of Korea, Vietnam and Japan as well.

Japan features hierarchically-organized companies and the Japanese place a high value on relationships (see Japanese work environment).[53] Korean businesses also adhere to Confucian values, and are structured around a patriarchal family governed by filial piety (孝順) between management and a company's employees.[54]

Before European imperialism, East Asia has always been one of the largest economies in the world, whose output had mostly been driven by China and the Silk Road.

During the Industrial Revolution, East Asia modernized and became an area of economic power starting with the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century when Japan rapidly transformed itself into the only industrial power outside the North Atlantic area.[55] Japan's early industrial economy reached its height in World War II (1939-1945) when it expanded its empire and became a major world power.

Post WW2 (Tiger economies)

Following Japanese defeat, economic collapse after the war, and US military occupation, Japan's economy recovered in the 1950s with the post-war economic miracle in which rapid growth propelled the country to become the world's second-largest economy by the 1980s.

Since the Korean War and again under US military occupation, South Korea has experienced its postwar economic miracle called the Miracle on the Han River, with the rise of global tech industry leaders like Samsung, LG, etc. As of 2019 its economy is the 4th largest in Asia and the 11th largest in the world.

Hong Kong became one of the Four Asian Tiger economies, developing strong textile and manufacturing economies.[56] South Korea followed a similar route, developing the textile industry.[56] Following in the footsteps of Hong Kong and Korea, Taiwan and Singapore quickly industrialized through government policies. By 1997, all four of the Asian Tiger economies had joined Japan as economically developed nations.

As of 2019, South Korean and Japanese growth have stagnated (see also Lost Decade), and present growth in East Asia has now shifted to China and to the Tiger Cub Economies of Southeast Asia.[57][58][59][60]

Modern era

Since the Chinese economic reform, China has become the 2nd and 1st-largest economy in the world respectively by nominal GDP and GDP (PPP).

The Pearl River Delta is one of the top startup regions (comparable with Beijing and Shanghai) in East Asia, featuring some of the world's top drone companies, such as DJI.

Up until the early 2010s, Vietnamese trade was heavily dependent on China, and many Chinese-Vietnamese speak both Cantonese and Vietnamese, which share many linguistic similarities. Vietnam, one of Next Eleven countries as of 2005, is regarded as a rising economic power in Southeast Asia.[61]

East Asia participates in numerous global economic organizations including:

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization

- Bamboo Network

- ASEAN, ASEAN Plus Three, AFTA

- East Asia Summit

- East Asian Community

See also

- Sinosphere (linguistics)

- Adoption of Chinese literary culture

- East Asia

- Sinophone world

- Sinoxenic

- Culture of China

- Culture of Korea

- Culture of Japan

- Culture of Hong Kong

- Culture of Singapore

- Culture of Taiwan

- Culture of Vietnam

- List of tributaries of China

- Four Asian Tigers

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

References

Citations

- Benjamin A Elman, ed (2014). Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919. Brill. ISBN 900427927X.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Nanxiu Qian et al, eds (2020). Rethinking the Sinosphere: Poetics, Aesthetics, and Identity Formation. Cambria Press. ISBN 1604979909.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Nanxiu Qian et al, eds (2020). Reexamining the Sinosphere: Cultural Transmissions and Transformations in East Asia. Cambria Press. ISBN 1604979879.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Jeffrey L. Richey (2013). Confucius in East Asia: Confucianism’s History in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Association for Asian Studies. ISBN 0924304731., Rutgers University, ed. (2010). East Asian Confucianism: Interactions and Innovations. Rutgers University. ISBN 0615389325.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)Chun-chieh Huang, ed. (2015). East Asian Confucianisms: Texts in Contexts. National Taiwan University Press and Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783847104087.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- L. Carrington Goodrich (2007). A Short History of the Chinese People. Sturgis Press. ISBN 978-1406769760.

- McCannon, John (19 March 2018). Barron's how to Prepare for the AP World History Examination. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 9780764118166.

- Formichi, Chiara (1 October 2013). Religious Pluralism, State and Society in Asia. Routledges. ISBN 9781134575428.

- Sthapitanond, Nithi; Mertens, Brian (19 March 2018). Architecture of Thailand: A Guide to Tradition and Contemporary Forms. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9789814260862.

- Winks, Robin (21 October 1999). The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume V: Historiography. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191542411.

- Rodriguez T. Senase, Jose (25 July 2019). "Qingdao Airlines launches inaugural flight to Sihanoukville". Khmer Times. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Rieffel, Lex (2010). Myanmar/Burma: inside challenges, outside interests. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0-8157-0505-5.

- Wang Hui, "'Modernity and 'Asia' in the Study of Chinese History," in Eckhardt Fuchs, Benedikt Stuchtey, eds.,Across cultural borders: historiography in global perspective (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 ISBN 978-0-7425-1768-4), p. 322.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (2003), ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary, University of Hawaii Press, p. 750.

- T. Watanabe, E. R. Skrzypczak, and P. Snowden (2003), Kenkyūsha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, Kenkyusha, p. 873. Compare Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

- Victor Mair, Sinophone and Sinosphere, Language Log, November 8, 2012.

- See the "family tree" of Toynbee's "civilizations" in any edition of Toynbee's work, or e.g. as Fig.1 on p.16 of: The Rhythms of History: A Universal Theory of Civilizations, By Stephen Blaha. Pingree-Hill Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-9720795-7-2.

- Sun, Lung-kee (2002). The Chinese National Character: From Nationalhood to Individuality. M.E. Sharpe. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7656-3936-3.

- Sun, Lung-kee (2002). The Chinese National Character: From Nationalhood to Individuality. M.E. Sharpe. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-7656-0826-0.

- Edwin O. Reischauer, "The Sinic World in Perspective," Foreign Affairs 52.2 (January 1974): 341-348. JSTOR

- The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996; ISBN 0684811642), p. 45

- William E. Davis (2006). Peace And Prosperity in an Age of Incivility. University Press of America. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7618-3248-5.

- Michail S. Blinnikov (2011). A Geography of Russia and Its Neighbors. Guilford Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-60623-933-9.

- Lung-kee Sun (2002). The Chinese National Character: From Nationalhood to Individuality. M.E. Sharpe. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7656-0826-0.

- Hugh Gusterson (2004). People of the bomb: portraits of America's nuclear complex. U of Minnesota Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8166-3860-4.

- McCannon, John (February 2002). How to Prepare for the AP World History. ISBN 9780764118166.

- Adi, Yoga (13 July 2017). "Top 8 Chinese Culture in Indonesia". Facts of Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Davidson, Alan (1981). Food in Motion: The Migration of Foodstuffs and Cookery Techniques : Proceedings : Oxford Symposium 1983. Oxford Symposium. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-907325-07-9.

- Wen S. Chern; Colin A. Carter; Shun-yi Shei (2000). Food security in Asia: economics and policies. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-78254-334-3.

- Kim, Kwang-Ok (1 February 2015). Re-Orienting Cuisine : East Asian Foodways in the Twenty-First Century. Berghahn Books, Incorporated. p. 14. ISBN 9781782385639.

- Ono, Sakyo. Shinto: The Kami Way. Pp 97–99, 103–104. Tuttle Publishing. 2004. ISBN 0-8048-3557-8

- Ono, Sakyo. Shinto: The Kami Way. Pp 51–52, 108. Tuttle Publishing. 2004. ISBN 0-8048-3557-8

- Markham, Ian S. & Ruparell, Tinu. Encountering Religion: an introduction to the religions of the world. pp 304–306 Blackwell Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-631-20674-4.

- Ono, Sakyo. Shinto: The Kami Way. Pg 12. Tuttle Publishing. 2004. ISBN 0-8048-3557-8

- Juergensmeyer, Mark (2005). Religion in global civil society. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-518835-6.

- Craig, Edward. Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. ISBN 0-19-285421-6 Craig 1998, p. 536.

- Essentials of Neo-Confucianism: Eight Major Philosophers of the Song and Ming Periods by Huang, Siu-chi. Huang 1999, p. 5.

- A Sourcebook of Chinese Philosophy by Chan, Wing-tsit. Chan 2002, p. 460.

- Jin, Li; Wuyun Pan; Yan, Shi; Zhang, Menghan (24 April 2019). "Phylogenetic evidence for Sino-Tibetan origin in northern China in the Late Neolithic". Nature. 569 (7754): 112–115. Bibcode:2019Natur.569..112Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1153-z. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31019300.

- Sagart, Laurent and Jacques, Guillaume and Lai, Yunfan and Ryder, Robin and Thouzeau, Valentin and Greenhill, Simon J. and List, Johann-Mattis. 2019. "Dated language phylogenies shed light on the ancestry of Sino-Tibetan". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 21. 10317-10322. doi:10.1073/pnas.1817972116

- DeFrancis, John, 1911-2009. (1977). Colonialism and language policy in Viet Nam. The Hague: Mouton. ISBN 9027976430. OCLC 4230408.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sohn, Ho-min. (1999). The Korean language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521361230. OCLC 40200082.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi. (1990). The languages of Japan. 柴谷, 方良, 1944- (Reprint 1994 ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521360706. OCLC 19456186.

- Ratliff, Martha Susan. (2010). Hmong-Mien language history. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 9780858836150. OCLC 741956124.

- "Why reading their own language gives Mongolians a headache". SoraNews24. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Zhou, Minglang, 1954- (24 October 2012). Multilingualism in China : the politics of writing reforms for minority languages, 1949-2002. Berlin. ISBN 9783110924596. OCLC 868954061.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kornicki, P.F. (2011), "A transnational approach to East Asian book history", in Chakravorty, Swapan; Gupta, Abhijit (eds.), New Word Order: Transnational Themes in Book History, Worldview Publications, pp. 65–79, ISBN 978-81-920651-1-3.Kornicki 2011, pp. 75–77

- Kornicki (2011), pp. 66–67.

- Miyake (2004), pp. 98–99.

- Kornicki (2011), p. 68.

- "Given Japan’s strong tradition of Chinese textual scholarship, encouraged further by visits by eminent Chinese scholars since the early twentieth century, Japan has been one of the birthplaces of modern sinology outside China" Early China - A Social and Cultural History, page 11. Cambridge University Press.

- Weijian, Chen. "Australia And New Zealand Are Ground Zero For Chinese Influence". NPR.org. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- "DOCUMENTO D'INTESA TRA IL GOVERNO DELLA REPUBBLICA ITALIANA E IL GOVERNO DELLA REPUBBLICA POPOLARE CINESE SULLA COLLABORAZIONE ALL'INTERNO DEL PROGETTO ECONOMICO "VIA DELLA SETA" E DELL'INIZIATIVA PER LE VIE MARITTIME DEL XXI° SECOLO".

- Where cultures meet; a cross-cultural comparison of business meeting styles. Hogeschool van Amsterdam. p. 69. ISBN 978-90-79646-17-3.

- Timothy Book; Hy V.. Luong (1999). Culture and economy: the shaping of capitalism in eastern Asia. University of Michigan Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-472-08598-9. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Aiko Ikeo (4 January 2002). Economic Development in Twentieth-Century East Asia: The International Context. Taylor & Francis. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-203-02704-2.

- Compare: J. James W. Harrington; Barney Warf (1995). Industrial Location: Principles, Practice, and Policy. Routledge. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-415-10479-1.

As the textile industry began to abandon places with high labor costs in the western industrialized world, it began to sprout up in a variety of Third World locations, in particular the famous 'Four Tiger' nations of East Asia: South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Textiles were particularly important in the early industrialization of South Korea, while garment production was more significant to Hong Kong.

- "Why South Korea risks following Japan into economic stagnation". Australian Financial Review. 21 August 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Abe, Naoki (12 February 2010). "Japan's Shrinking Economy". Brookings. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "The rise and demise of Asia's four little dragons". South China Morning Post. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "YPs' Guide To: Southeast Asia—How Tiger Cubs Are Becoming Rising Tigers". spe.org. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "The story behind Viet Nam's miracle growth". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

Sources

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Global communication without universal civilization. 1. Geneva, Switzerland: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Elman, Benjamin A (2014). Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 900427927X.

- Joshua Fogel, "The Sinic World," in Ainslie Thomas Embree, Carol Gluck, ed., Asia in Western and World History a Guide for Teaching. (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, Columbia Project on Asia in the Core Curriculum, 1997). ISBN 0585027331. Access may be limited to NetLibrary affiliated libraries.

- Fogel, Joshua A. (2009). Articulating the Sinosphere : Sino-Japanese relations in space and time. Edwin O. Reischauer Lectures ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03259-0.

- Holcombe, Charles (2011). "Introduction: What is East Asia". A history of East Asia : from the origins of civilization to the twenty-first century (1st published. ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0521731645.

- Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia, 221 B.C.-A.D. 907 ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Honolulu: Association for Asian Studies and University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0824824150.

- Huang, Chun-chieh (2015). East Asian Confucianisms: Texts in Contexts. Taipei and Göttingen, Germany: National Taiwan University Press and Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783847104087.

- Qian, Nanxiu (2020). Reexamining the Sinosphere: Cultural Transmissions and Transformations in East Asia. Amherst, N.Y.: Cambria Press. ISBN 1604979879.

- Qian, Nanxiu (2020). Rethinking the Sinosphere: Poetics, Aesthetics, and Identity Formation. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press. ISBN 1604979909.

- Reischauer, Edwin O. (1974). "The Sinic World in Perspective". Foreign Affairs. 52 (2): 341–348. doi:10.2307/20038053. JSTOR 20038053.

- Richey, Jeffrey L. (2013). Confucius in East Asia: Confucianism’s History in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies. ISBN 0924304731.

- Rutgers University, Confucius Institute (2010). East Asian Confucianism: Interactions and Innovations. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University. ISBN 0615389325.

External links

- Asia for Educators. Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University.

.svg.png)