Indian maritime history

Indian maritime history begins during the 3rd millennium BCE when inhabitants of the Indus Valley initiated maritime trading contact with Mesopotamia.[1] The Roman historian Strabo mentions an increase in Roman trade with India following the Roman annexation of Egypt.[2] Strabo reports that during the time when Aelius Gallus was Prefect of Egypt (26-24 BCE), he saw 120 ships ready to leave for India at the Red Sea port of Myos Hormos.[3] As trade between India and the Greco-Roman world increased spices became the main import from India to the Western world,[4] bypassing silk and other commodities.[5] Indians were present in Alexandria[6] while Christian and Jewish settlers from Rome continued to live in India long after the fall of the Roman Empire,[7] which resulted in Rome's loss of the Red Sea ports,[8] previously used to secure trade with India by the Greco-Roman world since the Ptolemaic dynasty.[9] The Indian commercial connection with South East Asia proved vital to the merchants of Arabia and Persia during the 7th–8th century.[10] A study published in 2013 found that some 11 percent of Aboriginal DNA is of Indian origin and suggests these immigrants arrived about 4,000 years ago, possibly at the same time dingoes first arrived in Australia.[11][12]

|

| History of science and technology in the Indian subcontinent |

|---|

| By subject |

|

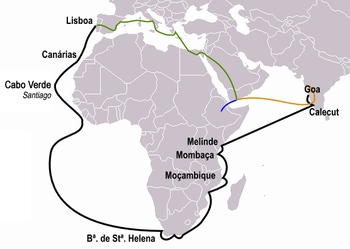

On orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, continuing to the eastern coast of Africa to Malindi to sail across the Indian Ocean to Calicut.[13] The wealth of the Indies was now open for the Europeans to explore.[13] The Portuguese Empire was the first European empire to grow from spice trade.[13]

National Maritime Day

5 April is celebrated as National Maritime Day in India. On this day in 1919, navigation history was created when SS Loyalty, the first ship of The Scindia Steam Navigation Company Ltd., journeyed to the United Kingdom, a crucial step for India's shipping history when sea routes were controlled by the British.

Prehistory

The region around the Indus river began to show visible increase in both the length and the frequency of maritime voyages by 3000 BCE.[14] Optimum conditions for viable long-distance voyages existed in this region by 2900 BCE.[15] Mesopotamian inscriptions indicate that Indian traders from the Indus valley—carrying copper, hardwoods, ivory, pearls, carnelian, and gold—were active in Mesopotamia during the reign of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE).[1] Gosch & Stearns write on the Indus Valley's pre-modern maritime travel:[16] Evidence exists that Harappans were bulk-shipping timber and special woods to Sumer on ships and luxury items such as lapis lazuli. The trade in lapis lazuli was carried out from northern Afghanistan over eastern Iran to Sumer but during the Mature Harappan period an Indus colony was established at Shortugai in Central Asia near the Badakshan mines and the lapis stones were brought overland to Lothal in Gujarat and shipped to Oman, Bahrain and Mesopotamia.

Archaeological research at sites in Mesopotamia, Bahrain, and Oman has led to the recovery of artefacts traceable to the Indus Valley civilisation, confirming the information on the inscriptions. Among the most important of these objects are stamp seals carved in soapstone, stone weights, and colourful carnelian beads....Most of the trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley was indirect. Shippers from both regions converged in Persian Gulf ports, especially on the island of Bahrain (known as Dilmun to the Sumerians). Numerous small Indus-style artefacts have been recovered at locations on Bahrain and further down the coast of the Arabian Peninsula in Oman. Stamp seals produced in Bahrain have been found at sites in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, strengthening the likelihood that the island may have acted as a redistribution point for goods coming from Mesopotamia and the Indus area....There are hints from the digs at Ur, a major Sumerian city-state on the Euphrates, that some Indus Valley merchants and artisans (bead makers) may have established communities in Mesopotamia.

The world's first dock at Lothal (2400 BCE) was located away from the main current to avoid deposition of silt.[17] Modern oceanographers have observed that the Harappans must have possessed great knowledge relating to tides in order to build such a dock on the ever-shifting course of the Sabarmati, as well as exemplary hydrography and maritime engineering.[17] This was the earliest known dock found in the world, equipped to berth and service ships.[17] It is speculated that Lothal engineers studied tidal movements, and their effects on brick-built structures, since the walls are of kiln-burnt bricks.[18] This knowledge also enabled them to select Lothal's location in the first place, as the Gulf of Khambhat has the highest tidal amplitude and ships can be sluiced through flow tides in the river estuary.[18] The engineers built a trapezoidal structure, with north-south arms of average 21.8 metres (71.5 ft), and east-west arms of 37 metres (121 ft).[18]

Excavations at Golbai Sasan in Odisha have shown a Neolithic culture dating to as early as ca. 2300 BC, followed by a Chalcolithic (copper age) culture and then an Iron Age culture starting around 900 BC. Tools found at this site indicate boat building, perhaps for coastal trade.[19] Fish bones, fishing hooks, barbed spears and harpoons show that fishing was an important part of the economy.[20] Some artefacts of the Chalcolithic period are similar to artefacts found in Vietnam, indicating possible contact with Indochina at a very early period.[19]

Early kingdoms

Indian cartography locates the Pole star, and other constellations of use in navigational charts.[21] These charts may have been in use by the beginning of the Common Era for purposes of navigation.[21] Detailed maps of considerable length describing the locations of settlements, sea shores, rivers, and mountains were also made.[22] The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions a time when sea trade between India and Egypt did not involve direct sailings.[23] The cargo under these situations was shipped to Aden:[23]

Eudaimon Arabia was called fortunate, being once a city, when, because ships neither came from India to Egypt nor did those from Egypt dare to go further but only came as far as this place, it received the cargoes from both, just as Alexandria receives goods brought from outside and from Egypt.

It should be mentioned here that Tamil Pandya embassies were received by Augustus Caesar and Roman historians mention a total of four embassies from the Tamil country. Pliny famously mentions the expenditure of one million sestertii every year on goods such pepper, fine cloth and gems from the southern coasts of India. He also mentions 10,000 horses shipped to this region each year. Tamil and southern Sanskrit name inscriptions have been found in Luxor in Egypt. In turn Tamil literature from the Classical period mentions foreign ships arriving for trade and paying in gold for products.

The first clear mention of a navy occurs in the mythological epic Mahabharata.[24] Historically, however, the first attested attempt to organise a navy in India, as described by Megasthenes (c. 350—290 BCE), is attributed to Chandragupta Maurya (reign 322—298 BCE).[24] The Mauryan empire (322–185 BCE) navy continued till the times of emperor Ashoka (reign 273—32 BCE), who used it to send massive diplomatic missions to Greece, Syria, Egypt, Cyrene, Macedonia and Epirus.[24] Following nomadic interference in Siberia—one of the sources for India's bullion—India diverted its attention to the Malay peninsula, which became its new source for gold and was soon exposed to the world via a series of maritime trade routes.[25] The period under the Mauryan empire also witnessed various other regions of the world engage increasingly in the Indian Ocean maritime voyages.[25]

According to the historian Strabo (II.5.12.) the Roman trade with India trade initiated by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE kept increasing.[3] Indian ships sailed to Egypt as the thriving maritime routes of Southern Asia were not under the control of a single power.[26] In India, the ports of Barbaricum (modern Karachi), Barygaza, Muziris, Korkai, Kaveripattinam and Arikamedu on the southern tip of India were the main centres of this trade.[27] The Periplus Maris Erythraei describes Greco—Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, topaz, coral, storax, frankincense, vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "costus, bdellium, lycium, nard, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Seric skins, cotton cloth, silk yarn, and indigo".[27] In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth.[27]

The Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum was involved in the Indian Ocean trade network and was influenced by Roman culture and Indian architecture.[7] Traces of Indian influences are visible in Roman works of silver and ivory, or in Egyptian cotton and silk fabrics used for sale in Europe.[6] The Indian presence in Alexandria may have influenced the culture but little is known about the manner of this influence.[6] Clement of Alexandria mentions the Buddha in his writings and other Indian religions find mentions in other texts of the period.[6] The Indians were present in Alexandria[6] and Christian and Jewish settlers from Rome continued to live in India long after the fall of the Roman Empire,[7] which resulted in Rome's loss of the Red Sea ports,[8] previously used to secure trade with India by the Greco—Roman world since the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[9]

Early Common Era—High Middle Ages

During this period, Hindu and Buddhist religious establishments of Southeast Asia came to be associated with economic activity and commerce as patrons entrusted large funds which would later be used to benefit local economy by estate management, craftsmanship and promotion of trading activities.[30] Buddhism, in particular, travelled alongside the maritime trade, promoting coinage, art and literacy.[31] This route caused the intermixing of many artistic and cultural influences, Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian and Chinese, Greco-Buddhist art represents one such vivid examples of this interaction.[32] Buddha was first depicted as human in the Kushan period with intermixing of Greek and Indian elements, and the influence of this Greco-Buddhist art can be found in later Buddhist art in China and throughout countries on the Silk Road.[33] Ashoka and after him his successors of Kalinga, Pallava and Chola empires along with their vassals Pandya and Chera dynasties, as well as Vijayanagra empire all played a vital role in expanding Indianisation, extending Indian maritime trade and growth of Hinduism and Buddhism. Port of Kollam is an example of important trade port in Maritime Silk Route.

Maritime Silk Route, which flourished between the 2nd century BC and 15th century AD connected China, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Arabian peninsula, Somalia, Egypt and Europe.[34] Despite its association with China in recent centuries, the Maritime Silk Route was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia, Tamil merchants in India and Southeast Asia, Greco-Roman merchants in East Africa, India, Ceylon and Indochina, and by Persian and Arab traders in the Arabian Sea and beyond.[35] Prior to the 10th century, the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian traders, although Tamil and Persian traders also sailed them.[35] For most of its history, Austronesian thalassocracies controlled the flow of the Maritime Silk Road, especially the polities around the straits of Malacca and Bangka, the Malay peninsula, and the Mekong delta; although Chinese records misidentified these kingdoms as being "Indian" due to the Indianization of these regions.[35] The route was influential in the early spread of Hinduism and Buddhism to the east.[36] The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlier Austronesian spice trade networks of Islander Southeast Asians with Sri Lanka and Southern India (established 1000 to 600 BCE).[37][38]

Kalinga (in 3rd century BCE was annexed by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka) and Vijayanagara Empire (1336-1646) also established footholds in Malaya, Sumatra and Western Java. Maritime history of Odisha, known as Kalinga in ancient times, started before 350 BC according to early sources. The people of this region of eastern India along the coast of the Bay of Bengal sailed up and down the Indian coast, and travelled to Indo China and throughout Maritime Southeast Asia, introducing elements of their culture to the people with whom they traded. The 6th century Manjusrimulakalpa mentions the Bay of Bengal as 'Kalingodra' and historically the Bay of Bengal has been called 'Kalinga Sagara' (both Kalingodra and Kalinga Sagara mean Kalinga Sea), indicating the importance of Kalinga in the maritime trade.[40] The old traditions are still celebrated in the annual Bali Jatra, or Boita-Bandana festival held for five days in October / November.[41]

Textiles from India were in demand in Egypt, East Africa, and the Mediterranean between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, and these regions became overseas markets for Indian exports.[25] In Java and Borneo, the introduction of Indian culture created a demand for aromatics, and trading posts here later served Chinese and Arab markets.[10] The Periplus Maris Erythraei names several Indian ports from where large ships sailed in an easterly direction to Chryse.[42] Products from the Maluku Islands that were shipped across the ports of Arabia to the Near East passed through the ports of India and Sri Lanka.[43] After reaching either the Indian or the Sri Lankan ports, products were sometimes shipped to East Africa, where they were used for a variety of purposes including burial rites.[43]

Indian spice exports find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850), al-Ghafiqi (1150 CE), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).[43] Chinese traveler Xuanzang mentions the town of Puri where "merchants depart for distant countries."[44] The Abbasid caliphate (750–1258 CE) used Alexandria, Damietta, Aden and Siraf as entry ports to India and China.[45] Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden paid tribute in form of musk, camphor, ambergris and sandalwood to Ibn Ziyad, the sultan of Yemen.[45]

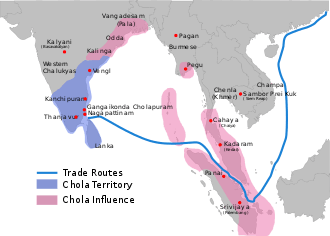

The Chola dynasty (200—1279) reached the peak of its influence and power during the medieval period.[46] Emperors Rajaraja Chola I (reigned 985-1014) and Rajendra Chola I (reigned 1012-1044) extended the Chola kingdom beyond the traditional limits.[47] At its peak, the Chola Empire stretched from the island of Sri Lanka in the south to the Godavari basin in the north.[48] The kingdoms along the east coast of India up to the river Ganges acknowledged Chola suzerainty.[49] Chola navies invaded and conquered Srivijaya and Srivijaya was the largest empire in Maritime Southeast Asia.[50] Goods and ideas from India began to play a major role in the "Indianization" of the wider world from this period.[51] The Cholas excelled in foreign trade and maritime activity, extending their influence overseas to China and Southeast Asia.[52] Towards the end of the 9th century, southern India had developed extensive maritime and commercial activity.[53][54] The Cholas, being in possession of parts of both the west and the east coasts of peninsular India, were at the forefront of these ventures.[55][56][57] The Tang dynasty (618–907) of China, the Srivijaya empire in Maritime Southeast Asia under the Sailendras, and the Abbasid caliphate at Baghdad were the main trading partners.[58]

Srivijaya empire, an Indianised Hindu-Buddhist empire founded at Palembang in 682 CE as indicated in Tang records, rose to dominate the trade in the region around the straits and the South China Sea emporium by controlling the trade in luxury aromatics and Buddhist artifacts from West Asia to a thriving Tang market.[35](p12) Chinese records also indicate that the early Chinese Buddhist pilgrims to South Asia booked passage with the Austronesian ships that traded in Chinese ports. Books written by Chinese monks like Wan Chen and Hui-Lin contain detailed accounts of the large trading vessels from Southeast Asia dating back to at least the 3rd century CE.[59]

One of the Pandya empire (3rd century BCE to 14th century CE) ruler Parantaka Nedumjadaiyan (765–790) and the Chera dynasty (absorbed into the Pandya political system by 10th/11th century AD) were a close ally of the Pallavas (275 CE to 897 CE).[60] Pallavamalla Nadivarman defeated the Pandya Varaguna with the help of a Chera king.[60] Cultural contacts between the Pallava court and the Chera country were common.[60] Eventually, Cheras dynasty were subsumed by Pandya dynasty, which in turn was subsumed by the Pallava dynasty.

.gif)

Kollam (also called Quilon or Desinganadu's) in coastal Kerala become operational in AD.825,[61] and has a high commercial reputation since the days of the Phoenicians and Romans,[62] The ruler of Kollam (who were vassals of pandya dynasty who in turn later became vassals of Chola dynasty) also used to exchange the embassies with Chinese rulers and there was flourishing Chinese settlement at Kollam.[63] The Indian commercial connection with Southeast Asia proved vital to the merchants of Arabia and Persia between the 7th and 8th centuries CE,[10] and merchant Sulaiman of Siraf in Persia (9th Century) found Kollam to be the only port in India, touched by the huge Chinese junks, on his way from Carton of Persian Gulf.[63] Marco Polo, the great Venician traveller, who was in Chinese service under Kublakhan in 1275, visited Kollam and other towns on the west coast, in his capacity as a Chinese mandarin.[63] Fed by the Chinese trade, port of Kollam was also mentioned by Ibn Battuta in the 14th century as one of the five Indian ports he had seen in the course of his travels during twenty-four years.[64]

Growth and development of agriculture in Kerala hinterlands brought about plentiful availability of surplus. The excess agricultural crops and grains were bartered for other necessities in angadis or trading centres, turning the ports to cities. Traders used coins especially in foreign trade to export spices, muslin, cotton, pearls and precious stones to countries of the west and received the wine, olive oil, amphora and terracotta pots from there. Egyptian dinars and Venetian ducats (1284-1797) were in great demand in medieval Kerala’s international trade.

The Arabs and the Chinese were important trade partners of medieval Kerala. Arab trade and navigation attained a new enthusiasm since the birth and spread of Islam. Four gold coins of Umayyad Caliphate (665-750 CE) found in Kothamangalam testifies the visit of Arab traders to Kerala in that period. With the formation of Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE) the Golden Age of Islam began and trade flourished as the religion was favorably disposed towards trade. Ninth century on wards the Arab trade to Malabar was raised to new esteems and saw many outposts of Muslim merchants. This, later on, became a strong element of Kerala Maritime History.

The Trade with Malabar resulted in the drainage of Chinese gold in abundance that the Song dynasty (1127-1279) prohibited the use of gold, silver and bronze in foreign trade in 1219 and silk fabrics and porcelain was ordered to be bartered against foreign goods. Pepper, coconut, fish, betel nuts, etc were exported from Malabar in exchange for gold, silver, colored satin, blue and white porcelain, musk, quicksilver and camphor from China

Late Middle Ages

Ma Huan (1413–51) reached Cochin and noted that Indian coins, known as fanam, were issued in Cochin and weighed a total of one fen and one li according to the Chinese standards.[65] They were of fine quality and could be exchanged in China for 15 silver coins of four-li weight each.[65]

On the orders of Manuel I of Portugal, four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1497, continuing to Malindi on the eastern coast of Africa, from there to sail across the Indian Ocean to Calicut.[13] Christian missionaries traveling with trade, such as Saint Francis Xavier, were instrumental in the spread of Christianity in the East.[66]

The first Dutch expedition left from Amsterdam (April 1595) for South East Asia.[67] Another Dutch convoy sailed in 1598 and returned one year later with 600,000 pounds of spices and other Indian products.[67] The United East India Company forged alliances with the principal producers of cloves and nutmeg.[67]

Shivaji Bhonsle (reign 1664—1680) maintained a navy under the charge of general Kanhoji Angre (served 1698—1729).[68] The initial advances of the Portuguese were checked by this navy, which also effectively relieved the traffic and commerce in India's west coast of Portuguese threat.[68] The Maratha navy also checked the English East India Company, until the navy itself underwent a decline due to the policies of general Nanasaheb (reign 1740 – 1761).[69]

Baba Makhan Shah Labana, a noted Sikh of the 17th century is known for trade in sea route to Gulf and Mediterranean region.

British Raj – Modern Period

The British East India Company shipped substantial quantities of spices during the early 17th century.[67] Rajesh Kadian (2006) examines the history of the British navy in as the British Raj was established in India:[70]

In 1830 ships of the British East India Company were designated as the Indian navy. However, in 1863, it was disbanded when Britain's Royal Navy took control of the Indian Ocean. About thirty years later, the few small Indian naval units were called the Royal Indian Marine (RIM). In the wake of World War I, Britain, exhausted in manpower and resources, opted for expansion of the RIM. Consequently, on 2 October 1934, the RIM was reincarnated as the Royal Indian Navy (RIN).

The Indian rulers weakened with the advent of the European powers. Shipbuilders, however, continued to build ships capable of carrying 800 to 1,000 tons. The shipbuilders at the Bombay Dockyard built ships like HMS Hindostan and HMS Ceylon, inducted into the Royal Navy. The historical ships made by Indian shipbuilders included HMS Asia (commanded by Edward Codrington during the Battle of Navarino in 1827), the frigate HMS Cornwallis (onboard which the Treaty of Nanking was signed in 1842), and HMS Minden (on which The Star Spangled Banner was composed by Francis Scott Key). David Arnold examines the role of Indian shipbuilders during the British Raj:[71]

Shipbuilding was a well-established craft at numerous points along the Indian coastline long before the arrival of the Europeans and was a significant factor in the high level of Indian maritime activity in the Indian Ocean region....As with cotton textiles, European trade was initially a stimulus to Indian shipbuilding: vessels built in ports like Masulipatam and Surat from Indian hardwoods by local craftsmen were cheaper and tougher than their European counterparts.

Between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries Indian shipyards produced a series of vessels incorporating these hybrid features. A large proportion of them were built in Bombay, where the Company had established a small shipyard. In 1736 Parsi carpenters were brought in from Surat to work there and, when their European supervisor died, one of the carpenters, Lowji Nuserwanji Wadia, was appointed Master Builder in his place.

Wadia oversaw the construction of thirty-five ships, twenty-one of them for the Company. Following his death in 1774, his sons took charge of the shipyard and between them built a further thirty ships over the next sixteen years. The Britannia, a ship of 749 tons launched in 1778, so impressed the Court of Directors when it reached Britain that several new ships were commissioned from Bombay, some of which later passed into the hands of the Royal Navy. In all, between 1736 and 1821, 159 ships of over 100 tons were built at Bombay, including 15 of over 1,000 tons. Ships constructed at Bombay in its heyday were said to be ‘vastly superior to anything built anywhere else in the world’.

Contemporary Era (1947–present)

Military

In 1947, the Republic of India’s navy consisted of 33 ships, and 538 officers to secure a coastline of more than 4,660 miles (7,500 km) and 1,280 islands.[70] The Indian navy conducted annual Joint Exercises with other Commonwealth navies throughout the 1950s.[70] The navy saw action during various of the country's wars, including Indian integration of Junagadh,[72] the liberation of Goa,[73] the 1965 war, and the 1971 war.[74] Following difficulty in obtaining spare parts from the Soviet Union, India also embarked upon a massive indigenous naval designing and production programme aimed at manufacturing destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and submarines.[70]

India's Coast Guard Act was passed in August 1978.[70] The Indian Coast Guard participated in counter terrorism operations such as Operation Cactus.[70] During contemporary times the Indian navy was commissioned in several United Nations peacekeeping missions.[70] The navy also repatriated Indian nationals from Kuwait during the first Gulf War.[70] Rajesh Kadian (2006) holds that: "During the Kargil War (1999), the aggressive posture adopted by the navy played a role in convincing Islamabad and Washington that a larger conflict loomed unless Pakistan withdrew from the heights.".[70]

As a result of the growing strategic ties with the western world the Indian navy has conducted joint exercises with its western counterparts, including the United States Navy, and has obtained latest naval equipment from its western allies.[70] Better relations with the United States of America and Israel have led to joint patrolling of the Straits of Malacca.[70]

Civil

The following table gives the detailed data about the major ports of India for the financial year 2005–06 and percentage growth over 2004–05 (Source: Indian Ports Association):

| Name | Cargo Handled (06-07) '000 tonnes | % Increase (over 05-06) | Vessel Traffic (05-06) | % Increase (over 04-05) | Container Traffic (05-06) '000 TEUs | % Increase (over 04-05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolkata (Kolkata Dock System & Haldia Dock Complex) | 55,050 | 3.59% | 2,853 | 07.50% | 313 | 09.06% |

| Paradip | 38,517 | 16.33% | 1,330 | 10.01% | 3 | 50.00% |

| Visakhapatnam | 56,386 | 1.05% | 2,109 | 14.43% | 47 | 04.44% |

| Chennai | 53,798 | 13.05% | 1,857 | 11.26% | 735 | 19.12% |

| Tuticorin | 18,001 | 05.03% | 1,576 | 06.56% | 321 | 04.56% |

| Cochin | 15,314 | 10.28% | 1,225 | 09.38% | 203 | 09.73% |

| New Mangalore Port | 32,042 | -06.99% | 1,087 | 01.87% | 10 | 11.11% |

| Mormugao | 34,241 | 08.06% | 642 | -03.31% | 9 | -10.00% |

| Mumbai | 52,364 | 18.50% | 2,153 | 14.34% | 159 | -27.40% |

| J.N.P.T, Navi Mumbai | 44,818 | 18.45% | 2,395 | 03.06% | 2,267 | -04.39% |

| Ennore | 10,714 | 16.86% | 173 | 01.17% | ||

| Kandla | 52,982 | 15.41% | 2,124 | 09.48% | 148 | -18.23% |

| All Indian Ports | 463,843 | 9.51% | 19,796 | 08.64% | 4,744 | 12.07% |

See also

- Spread of Indian influence through maritiem routes

- Trading routes

- Indo-Roman trade relations

- Indian Ocean trade

- Indus-Mesopotamia relations

- Silk route

- Ancient maritime history

Notes

- Gosch & Stearns, 12

- Young, 20

- "At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Kingdom of Aksum (Ethiopia), and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise." —"The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917".

- Ball, 131

- Ball, 137

- Lach, 18

- Curtin, 100

- Holl, 9

- Lindsay, 101

- Donkin, 59

- Yong, Ed (2013). "Aboriginal Australian genomes reveal Indian ancestry". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.12219.

- "Migration from India to Australia". Nature. 493 (7432): 274. 2013. doi:10.1038/493274c.

- "Gama, Vasco da". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press.

- Gosch & Stearns, 7

- Gosch & Stearns, 9

- Gosch & Stearns, 12–13

- Rao, 27–28

- Rao, 28–29

- Sushanta Ku. Patra & Benudhar Patra. "ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE MARITIME HISTORY OF ANCIENT ORISSA" (PDF). OHRJ, Vol. XLVII, No. 2. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Sila Tripati. "Early Maritime Activities of Orissa on the East Coast of India: Linkages in Trade and Cultural Developments" (PDF). Marine Archaeology Centre, National Institute of Oceanography, Dona Paula, Goa. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- Sircar, 330

- Sircar, 327

- Young, 19

- Chakravarti (1930)

- Shaffer, 309

- Lach, 13

- Halsall, Paul. "Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". Fordham University.

- Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar, 1933– (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- Donkin, 67

- Donkin, 69

- Xinru, Liu,The Silk Road in World History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 21.

- Foltz, Richard C. (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. New York: St Martin's Press. p. 45.

- "Maritime Silk Road". SEAArch.

- Guan, Kwa Chong (2016). "The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea" (PDF). NSC Working Paper (23): 1–30.

- Sen, Tansen (3 February 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15.

- Bellina, Bérénice (2014). "Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road". In Guy, John (ed.). Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to 8th century. Yale University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 9781588395245.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean" (PDF). In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0415100540.

- The Journal of Orissan History, Volumes 13-15. Orissa History Congress. 1995. p. 54.

- "Bali Yatra". Orissa Tourism. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Donkin, 64

- Donkin, 92

- Donkin, 65

- Donkin, 91–92

- Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, 5

- Kulke & Rothermund, 115

- Rajendra Chola I completed the conquest of the island of Sri Lanka and captured the Sinhala king Mahinda V. Nilakanta Sastri, The CōĻas pp 194–210.

- Majumdar, 407

- The kadaram campaign is first mentioned in Rajendra's inscriptions dating from his 14th year. The name of the Srivijaya king was Sangrama Vijayatungavarman—Nilakanta Sastri, The CōĻas, 211–220.

-

Shaffer, Lynda Noreen (2001). "Southernization". In Adas, Michael (ed.). Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History. Critical perspectives on the past. American Historical Association. Temple University Press. p. 308. ISBN 9781566398329. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

The term 'southernization' [...] is used [...] to refer to a multifaceted process that began in Southern Asia and spread from there [...]. The process included [...] many interrelated strands of development[:] [...] the metallurgical, the medical, [...] the literary [...] the development of mathematics; the production and marketing of subtropical or tropical spices; the pioneering of new trade routes; the cultivation, processing, and marketing of southern crops such as sugar and cotton; and the development of various related technologies. [...] Southernization was well under way in Southern Asia by the fifth century C.E.

- Kulke & Rothermund, 116–117.

- Kulke & Rothermund, 12

- Kulke & Rothermund, 118

- Kulke & Rothermund, 124

- Tripathi, 465

- Tripathi, 477

- Nilakanta Sastri, The CōĻas, 604

- McGrail, Seán (2001). Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to the Medieval Times. Oxford University Press. pp. 289–293. ISBN 9780199271863.

- See A History of South India – pp 146 – 147

- "Page No.710, International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania". Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1958) [1935]. History of South India (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- "Short History of Kollam". Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Kollam - Mathrubhumi Archived 9 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Chaudhuri, 223

- Corn 1999, pp 68-. "If the Portuguese had wrested the spice trade from the Arabs in those distant lands, then why shouldn't a people enslaved by a false doctrine be likewise freed? This rhetorical question became for Xavier his ultimate concern. It was Portugal's supremacy on the seas and in the spice trade that allowed it to flourish."

- Donkin, 169

- Sardesai, 53–56, Shivaji Bhonsle and Heirs

- Sardesai, 293–296, Peshwai and Pentarchy

- Kadian (2006)

- Arnold, 101–102

- The navy was used in national integration by ferrying troops and securing the coast during the Junagadh state operations—Rajesh Kadian (2006).

- the Indian navy, among other actions, sank the Portuguese frigate Afonso de Albuquerque—Rajesh Kadian (2006).

- The navy's fortunes were greatly restored in 1971. After East Pakistan (Bangladesh) seceded, leading to civil war between Pakistan's two wings, the Indian navy trained four task forces of riverine guerrillas. Those frogmen sank or damaged over 100,000 tons of shipping in four months and disrupted ports and inland waterways, the lifeline of the country. In December, after the war formally started, an imaginative, daring raid by Osa missile boats on Karachi harbor sank two warships, damaged others, and ignited oil storage facilities. The Indian armed forces conducted amphibious landings for the first time toward the end of the war—Rajesh Kadian (2006).

Bibliography

- Radhakumud Mookerji (1912). Indian Shipping - A history of the sea-borne trade and maritime activity of the Indians from the earliest times. Longmans, Green and Co., Bombay.

- Mehta, Asoka (1940). Indian Shipping: A case study of the working of Imperialism. N.T.Shroff, Bombay.

References

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Indian maritime history |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maritime history of India. |

- Arnold, David (2004), The New Cambridge History of India: Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-56319-4.

- Ball, Warwick (2000), Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-11376-8.

- Chakravarti, P. C. (1930), "Naval Warfare in ancient India", The Indian Historical Quarterly, 4 (4): 645–664.

- Chaudhuri, K. N. (1985), Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-28542-9.

- Corn, Charles (1999) [First published 1998], The Scents of Eden: A History of the Spice Trade, Kodansha, ISBN 1-56836-249-8.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond etc. (1984), Cross-Cultural Trade in World History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-26931-8.

- Donkin, Robin A. (2003), Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans, Diane Publishing Company, ISBN 0-87169-248-1.

- Gosch, Stephen S. & Stearns, Peter N. (2007), Premodern Travel in World History, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-203-92695-1.

- Hermann & Rothermund [2000] (2001), A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32920-5.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (2003), Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements, Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-0407-1.

- Kadian, Rajesh (2006), "Armed Forces", Encyclopedia of India (vol. 1) edited by Stanley Wolpet, pp. 47–55.

- Kulke & Rothermund [2000] (2001), A History of India, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32920-5.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994), Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-46731-7.

- Lindsay, W.S. (2006), History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 0-543-94253-8.

- Majumdar, R.C. (1987), Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN 81-208-0436-8.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A [1935] (1984), The CōĻas, University of Madras.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A [1955] (2002), A History of South India, Oxford University Press.

- K.M. Panikkar, 1945: India and the Indian Ocean: an essay on the influence of sea power on Indian history

- Rao, S. R. (1985), Lothal, Archaeological Survey of India.

- Rao, S. R. The Lost City of Dvaraka, National Institute of Oceanography, ISBN 81-86471-48-0 (1999)

- Rao, S. R. Marine Archaeology in India, Delhi: Publications Division, ISBN 81-230-0785-X (2001)

- Sardesai, D.R. (2006), "Peshwai and Pentarchy", Encyclopedia of India (vol. 3) edited by Stanley Wolpet, pp. 293–296.

- Sardesai, D.R. (2006), "Shivaji Bhonsle and Heirs", Encyclopedia of India (vol. 4) edited by Stanley Wolpet, pp. 53–56.

- Shaffer, Lynda N. (2001), "Southernization", Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History edited by Michael Adas, Temple University Press, ISBN 1-56639-832-0.

- Sircar, D.C. (1990), Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-0690-5.

- Tripathi, Rama Sankar (1967), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass Publications, ISBN 81-208-0018-4.

- Young, Gary Keith (2001), Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC-AD 305, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24219-3.

- Medieval Kerala’s Maritime trade history with Arabs and Chinese https://www.tyndisheritage.com/the-amazing-stories-of-kerala-maritime-history