Department for International Development

The Department for International Development (DFID) was a United Kingdom government department responsible for administering overseas aid. The goal of the department is "to promote sustainable development and eliminate world poverty". DFID is headed by the United Kingdom's Secretary of State for International Development. The position has been held since 13 February 2020 by Anne-Marie Trevelyan. In a 2010 report by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), DFID was described as "an international development leader in times of global crisis".[1] The UK aid logo is often used to publicly acknowledge DFID's development programmes are funded by UK taxpayers.

| |

.jpg) Department for International Development (London office) (far right) | |

| Department overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1997 |

| Preceding Department |

|

| Dissolved | September 2020 |

| Superseding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | United Kingdom |

| Headquarters | 22 Whitehall, London, England East Kilbride, Scotland |

| Annual budget | £13.4bn |

| Ministers responsible |

|

| Department executive |

|

| Website | www |

DFID's main programme areas of work are Education, Health, Social Services, Water Supply and Sanitation, Government and Civil Society, Economic Sector (including Infrastructure, Production Sectors and Developing Planning), Environment Protection, Research, and Humanitarian Assistance.

In 2009/10 DFID’s Gross Public Expenditure on Development was £6.65bn. Of this £3.96bn was spent on Bilateral Aid (including debt relief, humanitarian assistance and project funding) and £2.46bn was spent on Multilateral Aid (including support to the EU, World Bank, UN and other related agencies).[2] Although the Department for International Development’s foreign aid budget was not affected by the cuts outlined by the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s 2010 spending review, DFID will see their administration budgets slashed by approximately 19 percent over the next four years. This would mean a reduction in back-office costs to account for only 2 percent of their total spend by 2015.[3]

In June 2013 as part of the 2013 Spending Round outcomes it was announced that DFID's total programme budget would increase to £10.3bn in 2014/15 and £11.1bn in 2015/16 to help meet the UK government's commitment to spend 0.7% of GNI (Gross National Income) on ODA (Official Development Assistance). DFID is responsible for the majority of UK ODA; projected to total £11.7bn in 2014/15 and £12.2bn in 2015/16.[4] According to the OECD, 2019 official development assistance from the United Kingdom increased 2.2% to 19.4 billion.[5]

Ministers

The DFID Ministers are as follows:[6]

| Minister | Rank | Portfolio (by geographic region) |

|---|---|---|

| The Rt Hon. Anne-Marie Trevelyan MP | Secretary of State for International Development | Overall responsibility for the department; Cabinet and Cabinet Committees; National Security Council; All major spending decisions and overall delivery and management of 0.7%; Communications. |

| The Rt Hon. James Cleverly MP | Minister of State for Middle East & North Africa (jointly with FCO) | Middle East and North Africa; conflict, humanitarian issues, human security; CHASE (Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department); Stabilisation Unit; defence and international security; Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OCSE) and Council of Europe; Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF); safeguarding. |

| The Rt Hon. The Lord Goldsmith of Richmond Park PC | Minister of State for Pacific and the Environment (jointly with FCO and DEFRA) | Climate change, environment and conservation, biodiversity; oceans; Oceania; Blue Belt. |

| Nigel Adams MP | Minister of State for Asia (Jointly with FCO) | East Asia and South East Asia; economic diplomacy; trade; Economics Unit; Prosperity Fund; soft power, including British Council, BBC World Service and scholarships; third-country agreements; consular. |

| The Rt Hon. The Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon | Minister of State for South Asia and the Commonwealth (Jointly with FCO) | South Asia; Commonwealth; UN and multilateral; governance and democracy; open societies and anti-corruption; human rights, including Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI); treaty policy and practice; sanctions; departmental operations: human resources and estates. |

| James Duddridge MP | Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Africa (Jointly with FCO) | Sub-Saharan Africa; economic development; international financial institutions; CDC (UK government's development finance institution). |

| Wendy Morton MP | Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for the European Neighbourhood and the Americas (Jointly with FCO) | East and South-East Europe; Central Asia; Americas; health, global health security, neglected tropical diseases; water and sanitation; nutrition; Global Fund, GAVI (the Vaccine Alliance). |

| The Rt Hon. The Baroness Sugg | Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for the Overseas Territories and Sustainable Development (Jointly with FCO) | Overseas Territories; children, education and youth (including girls' education); sexual and reproductive health and rights, women and girls, LGBT, civil society, inclusive societies, disability; global partnerships and Sustainable Development Goals; departmental operations: finance and protocol |

The current Permanent Secretary is Matthew Rycroft, who assumed office in January 2018.

Mission

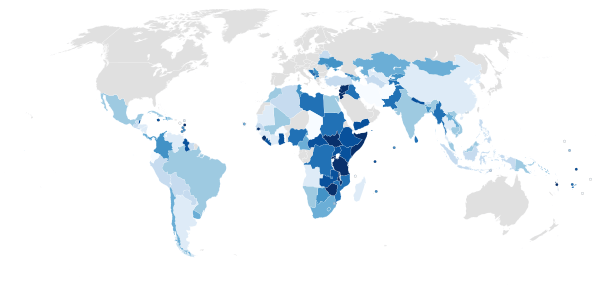

.jpg)

The main piece of legislation governing DFID's work is the International Development Act,[7] which came into force on 17 June 2002, replacing the Overseas Development and Co-operation Act 1980. The Act makes poverty reduction the focus of DFID's work, and effectively outlaws tied aid.[8]

As well as responding to disasters and emergencies, DFID works to support the United Nations' eight Millennium Development Goals, namely to:

- Halve the number of people living in extreme poverty and hunger

- Ensure that all children receive primary education

- Promote sexual equality and give women a stronger voice

- Reduce child death rates

- Improve the health of mothers

- Combat HIV & AIDS, malaria and other diseases

- Make sure the environment is protected

- Build a global partnership for those working in development.

all with a 2015 deadline.

Former Secretary of State Hilary Benn has indicated that on current trends, we will not achieve the Millennium Development Goals by 2015.[9] Although by 2010, mainly thanks to high growth in India and China who had 62% of the world's poor in 1990 there has been significant global progress towards meeting the millennium goals.[10]

History

.jpg)

The Department has its origins in the Ministry of Overseas Development (ODM) created during the Labour government of 1964–70, which combined the functions of the Department of Technical Cooperation and the overseas aid policy functions of the Foreign, Commonwealth Relations, and Colonial Offices and of other government departments.

After the election of a Conservative government in October 1970, the Ministry of Overseas Development was incorporated into the Foreign Office and renamed the Overseas Development Administration (ODA). The ODA was overseen by a minister of state in the Foreign Office who was accountable to the Foreign Secretary. Though it became a section of the Foreign Office, the ODA was relatively self-contained with its own minister, and the policies, procedures, and staff remained largely intact.

When a Labour government was returned to office in 1974, it announced that there would once again be a separate Ministry of Overseas Development with its own minister. From June 1975 the powers of the minister for overseas development were formally transferred to the Foreign Secretary.

In 1977, partly to shore up its difficult relations with UK business, the government introduced the Aid and Trade Provision. This enabled aid to be linked to nonconcessionary export credits, with both aid and export credits tied to procurement of British goods and services. Pressure for this provision from UK businesses and the Department of Trade and Industry arose in part because of the introduction of French mixed credit programmes, which had begun to offer French government support from aid funds for exports, including for projects in countries to which France had not previously given substantial aid.

After the election of the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher in 1979, the ministry was transferred back to the Foreign Office, as a functional wing again named the Overseas Development Administration. The ODA continued to be represented in the cabinet by the foreign secretary while the minister for overseas development, who had day-to-day responsibility for development matters, held the rank of minister of state within the Foreign Office.

In the 1980s part of the agency's operations was relocated to East Kilbride, with a view to creating jobs in an area subject to long-term industrial decline.

The Department was separated from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office when a Labour government returned in 1997; however, the Department and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office will be brought together to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office once again by the Conservatives under Boris Johnson in 2020.

DFID or the ODA's role has been under:

| In Cabinet | Outside Cabinet | |

|---|---|---|

| Separate Government Department | 1964–67 1997–present | 1961–64 1967–70 1974–75 |

| Answerable to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) | 1975–76 | 1970–74 1977–79 1979–97 |

Over its history the department for international development and its predecessors have been independent departments or part of the foreign office.[11] In 1997 Labour separated the Department for International Development from the Foreign Office. They also reduced the amount of aid tied to purchasing British goods and services which often led to aid being spent ineffectually.[12]

Along with the Nordic countries, DFID has generally avoided setting up its own programmes, in order to avoid creating unnecessary bureaucracy.[13] To achieve this, DFID distributes most of its money to governments and other international organisations that have already developed suitable programmes, and lets them distribute the money as efficiently as possible.[13] In July 2009, DFID rebranded all its aid programmes with the UK aid logo, to make clear the contributions are coming from the people of the United Kingdom.[14][15] While the decision met with some controversy among aid workers at the time, Commons International Development Select Committee Chairman Malcolm Bruce explained the rebranding saying "the name DFID does not reflect the fact that this is a British organisation; it could be anything. The Americans have USAID, Canada has got CIDA."[16]

The National Audit Office (NAO) 2009 Performance Management review[17] looked at how DFID has restructured its performance management arrangements over the last six years. The report responded to a request from DFID’s Accounting Officer to re-visit the topic periodically, which the Comptroller and Auditor General agreed would be valuable. The study found that DFID had improved in its general scrutiny of progress in reducing poverty and of progress towards divisional goals, however noted that there was still clear scope for further improvement.

In 2016, DFID was taken to task with accusations of misappropriation of funding in the British Overseas Territory of Montserrat. Whistleblower Sean McLaughlin commenced legal action against the Department in the Eastern Caribbean Court,[18] questioning the DFID fraud investigation process.

On 16 June 2020, Boris Johnson announced that the Department for International Development and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office would be brought together to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office from 1st September the same year, centralising oversight of the UK foreign aid budget.[19] The stated aim, according to Prime Minister Johnson was to 'unite our aid with our diplomacy and bring them together in our international effort'. Three former British Prime Ministers (David Cameron, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair) criticised the plan.[20]

Pergau Dam

When it was the Overseas Development Administration, a scandal erupted concerning the UK funding of a hydroelectric dam on the Pergau River in Malaysia, near the Thai border. Building work began in 1991 with money from the UK foreign aid budget. Concurrently, the Malaysian government bought around £1 billion worth of arms from the UK. This linkage of arms deals to aid was inappropriate; it became the subject of a UK government inquiry from March 1994.[21]

Ethiopia

In February 2015, DFID ended its financial support for a controversial development project alleged to have helped the Ethiopian government fund a brutal resettlement programme.[22][23] Four million people were forced off their land by security forces while their homes and farms were sold to foreign investors. In early 2017 the department ended £5.2m of support for the all-girl Ethiopian acting and pop group Yegna, called Ethiopia's 'Spice Girls',[24] citing concerns about the effectiveness and value for money of the programme.[25][26]

Budget

In 2010, DFID were criticised for spending around £15 million a year in the UK, although this only accounts for 0.25% of their total budget.[27] £1.85 million was given to the Foreign Office to fund the Papal visit of Pope Benedict in September 2010, although a department spokesman said that "The contribution recognised the Catholic Church's role as a major provider of health and education services in developing countries".[28] There has also been criticism of some spending by international organisations with UNESCO and the FAO being particularly weak.[29] The government were also criticised for increasing the aid budget at a time where other departments were being cut. The head of the conservative pressure group TaxPayers' Alliance said that "The department should at least get the same treatment other high priority areas like science did – a cash freeze would save billions.".[30] In November 2015, DFID released a new policy document titled "UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest".[31] In 2010 the incoming coalition government promised to reduce back-office costs to only 2% of the budget and to improve transparency by publishing more on their website.[29]

The budget for 2011–12 was £6.7 billion including £1.4 billion of capital.[32]

When the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, a fund of more than £1 billion per year for tackling conflict and instability abroad, was created on 1 April 2015 under the control of the National Security Council,[33] £823 million was transferred from the DFID budget to the fund, £739 million of which was then administered by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and £42 million by the Ministry of Defence.[34][35] Subsequently, concern was expressed in the media that the UK aid budget was being spent on defence and foreign policy objectives and to support the work of other departments.[36][37][38]

International grants table

The following table lists committed funding from DFID for the top 15 sectors, as recorded in DFID's International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) publications. DFID joined IATI in January 2011 but also records grants before that point.[39] The sectors use the names from the DAC 5 Digit Sector list.[40]

| Committed funding (GBP millions) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Before 2011 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Sum |

| Material relief assistance and services | 527.6 | 213.2 | 318.3 | 494.1 | 758.1 | 492.0 | 231.1 | 0.0 | 3,034.4 |

| Emergency food aid | 479.0 | 181.7 | 347.4 | 269.6 | 353.3 | 137.4 | 148.2 | 0.0 | 1,916.5 |

| Primary education | 856.2 | 521.8 | 474.7 | 91.2 | 44.3 | 49.3 | 216.9 | 0.0 | 2,254.4 |

| Social/ welfare services | 980.6 | 268.4 | 225.8 | 376.6 | 32.3 | 235.8 | 40.3 | 0.0 | 2,159.8 |

| Environmental policy and administrative management | 400.2 | 194.3 | 284.0 | 107.2 | 300.8 | 136.4 | 113.2 | 0.0 | 1,536.2 |

| Public sector policy and administrative management | 1,352.4 | 151.1 | 249.1 | 159.0 | 251.3 | 109.8 | 115.6 | 0.0 | 2,388.4 |

| Education policy and administrative management | 1,153.6 | 328.4 | 504.2 | 64.1 | 101.1 | 10.8 | 6.4 | 1.5 | 2,170.1 |

| Multisector aid | 753.1 | 805.0 | 155.4 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1,733.5 |

| Relief co-ordination; protection and support services | 170.9 | 71.4 | 115.6 | 145.3 | 320.0 | 119.8 | 177.5 | 0.0 | 1,120.4 |

| Reproductive health care | 720.5 | 308.6 | 267.0 | 161.0 | 65.8 | 91.4 | 47.9 | 0.0 | 1,662.2 |

| Small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) development | 173.8 | 16.1 | 583.2 | 58.8 | 147.3 | 17.2 | 49.5 | 0.0 | 1,046.0 |

| Basic health care | 477.3 | 287.5 | 165.7 | 84.3 | 37.2 | 179.3 | 43.8 | 0.0 | 1,275.0 |

| Financial policy and administrative management | 520.8 | 51.5 | 285.4 | 56.7 | 101.4 | 12.3 | 49.2 | 0.0 | 1,077.2 |

| Agricultural development | 179.0 | 142.1 | 37.4 | 102.0 | 161.5 | 72.2 | 33.0 | 0.0 | 727.1 |

| Family planning | 236.8 | 175.6 | 136.4 | 75.7 | 38.0 | 44.7 | 31.1 | 0.0 | 738.3 |

| Other | 28,828.3 | 9,225.2 | 4,636.4 | 2,479.2 | 2,217.2 | 1,521.6 | 1,611.9 | 36.9 | 50,519.9 |

| Total | 37,810.1 | 12,941.7 | 8,785.8 | 4,733.0 | 4,939.3 | 3,231.6 | 2,916.4 | 38.5 | 75,396.4 |

DFID research

DFID is the largest bilateral donor of development-focused research. New science, technologies and ideas are crucial for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals, but global research investments are insufficient to match needs and do not focus on the priorities of the poor. Many technological and policy innovations require an international scale of research effort. For example, DFID was a major donor to the International LUBILOSA Programme: which developed a biological pesticide for locust control in support of small-holder farmers in the Sahel.

DFID Research commissions research to help fill this gap, aiming to ensure tangible outcomes on the livelihoods of the poor worldwide. They also seek to influence the international and UK research agendas, putting poverty reduction and the needs of the poor at the forefront of global research efforts.

DFID Research manages long-term research initiatives that cut across individual countries or regions, and only funds activities if there are clear opportunities and mechanisms for the research to have a significant impact on poverty.

Research is funded through a range of mechanisms, including Research Programme Consortia (RPCs), jointly with other funders of development research, with UK Research Councils and with multilateral agencies (such as the World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organisation, World Health Organisation).[41] Information on both DFID current research programmes and completed research can be found on the (R4D) portal Research4Development.[42] From November 2012 all new DFID-funded research will be subject to its DFID Research Open and Enhanced Access Policy.[43][44] International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell declared that this will ensure "that these findings get into the hands of those in the developing world who stand to gain most from putting them into practical use".[45]

DFID launched its first Research Strategy in April 2008.[46] This emphasises DFID's commitment to funding high quality research that aims to find solutions and ways of reducing global poverty. The new strategy identifies six priorities:

- Growth[47]

- Health[48]

- Sustainable Agriculture[49]

- Climate Change[50]

- Governance in Challenging Environments[51]

- Future Challenges and Opportunities[52]

The strategy also highlights three important cross-cutting areas, where DFID will invest more funding:

DFID recently reviewed progress on its Research Strategy[56]

Principles for Digital Development

In addition to DFID Research Open and Enhanced Access Policy,[43] DFID expects partners and suppliers to adhere to the Principles for Digital Development across all programming.[57] The Principles for Digital Development also feature in the "DFID Digital Strategy 2018 to 2020: Doing Development in a Digital World"[58]

Monitoring

DFID is scrutinised by the British House of Commons International Development Committee and the Independent Commission for Aid Impact.

See also

- British government departments

- List of development aid agencies

- Stabilisation Unit

References

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/departmental-report/2010/dfid-in-2009-10-revised-6-sept-2010.pdf

- "DFID's Aid Budget Spared from UK Spending Cuts - Devex".

- 2013 Spending Round Outcomes: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/209036/spending-round-2013-complete.pdf

- https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org//sites/ff4da321-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e331623-en&_csp_=b14d4f60505d057b456dd1730d8fcea3&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=chapter#

- "Department for International Development - GOV.UK". Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Legislation.gov.uk". www.opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 August 2005. Retrieved 9 August 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Global targets, local ingenuity". The Economist. 23 September 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- "Reforming Development Assistance: Lessons from the U.K. Experience" (PDF). Brookings Institution. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- "Development: Clare Short's clean sheet". The Economist. 6 November 1997. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- Elizabeth Pisani (2008). Wisdom of the Whores. Penguin. pp. 289, 293.

- "Departmental Marketing: 21 Jul 2009: Hansard Written Answers - TheyWorkForYou".

- "UK aid - standards for using the logo". DFID. 2 July 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Britain's Help to the third World to be rebranded UKAid The Independent, 4 July 2009

- "NAO Review - DFID: Progress in improving performance management - National Audit Office (NAO)".

- "Sean Ross Mclaughlin v Montserrat Development Corporation". Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Haynes, Deborah (16 June 2020). "Foreign Office and International Development merger will curb 'giant cashpoint' of UK aid, PM pledges". Sky News. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Smith, Beckie. "'Wrong and regressive': three former prime ministers condemn DfID-FCO merger". CSW. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Dam Lies", The Economist, November 2012

- British support for Ethiopia scheme withdrawn amid abuse allegations, 27 February 2015, Sam Jones, Mark Anderson, The Guardian, retrieved at 13 January 2016

- The refugee who took on the British government, 12 January 2016, Ben Rawlence, The Guardian, retrieved at 13 January 2016

- "Yegna, Ethiopia's 'Spice Girls', lose UK funding". BBC. 7 January 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

"We judge there are more effective ways to invest UK aid," a spokeswoman said,

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/department-international-development-priti-patel-defends-foreign-aid-ethiopian-spice-girls-yegna-a7483901.html

- "Update on DFID's partnership with Girl Effect - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Mendick, Robert (13 February 2010). "£50m of Government's international aid budget spent in the UK". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- "MPs query £1.85m overseas aid spent on Pope visit". BBC. 3 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "More is more?". The Economist. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2011. (subscription required)

- Copping, Jasper (15 January 2011). "Where our overseas aid goes: salsa in Cambridge, coffee in Yorkshire". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- "UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest - Publications - GOV.UK".

- Budget 2011 (PDF). London: HM Treasury. 2011. p. 48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- "Conflict, Stability and Security Fund inquiry launched". Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy. UK Parliament. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Lorna Booth (23 November 2015). "Spending Review 2015: the future of overseas aid". House of Commons Library. UK Parliament. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Main Estimate 2015/16 (PDF). Department for International Development (Report). UK Parliament. 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- John Mcdermott, Jim Pickard (20 November 2015). "Cash-strapped UK departments circle aid budget ahead of cuts". Financial Times. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Ben Quinn (24 September 2016). "More than a quarter of UK aid budget to fall prey to rival ministries by 2020". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Alex Scrivener (25 November 2016). "Do we really want the military spending our aid budget?". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "About - UK - Department for International Development (DFID)". IATI Registry. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "DAC 5 Digit Sector". The IATI Standard. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line".

- "DFID Research Open and Enhanced Access Policy".

- "Overseas aid transparency - GOV.UK".

- Jha, Alok (25 July 2012). "UK government will enforce open access to development research". The Guardian. London.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "DFID Finances Research Projects carried out by Finish Line". Archived from the original on 1 January 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- "Putting digital principles into practice in our aid programmes - DFID bloggers". dfid.blog.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "DFID Digital Strategy 2018 to 2020: Doing Development in a Digital World - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

Further reading

- Victoria C. Honeyman, "New Labour's overseas development aid policy – charity or self-interest?", Contemporary British History, vol. 33, no. 3 (2019), pp. 313–335.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Department for International Development. |

- DFID Homepage

- DFID's Research4Development (R4D) portal, which provides information on DFID-funded research

- International Citizen Service Funded by DFID, provides voluntary opportunities for young people aged 18–25

- Video clips

.svg.png)