Common moorhen

The common moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), also known as the waterhen or swamp chicken, is a bird species in the rail family (Rallidae). It is distributed across many parts of the Old World.[2]

| Common moorhen | |

|---|---|

_Photograph_by_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg) | |

| G. c. chloropus from Mangaon, Maharashtra, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Gallinula |

| Species: | G. chloropus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gallinula chloropus | |

| Subspecies | |

|

About 5, see text | |

| |

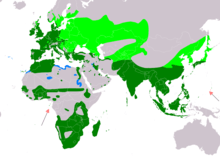

| Range of G. chloropus Breeding Resident Non-breeding Probably extinct | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The common moorhen lives around well-vegetated marshes, ponds, canals and other wetlands. The species is not found in the polar regions or many tropical rainforests. Elsewhere it is likely the most common rail species, except for the Eurasian coot in some regions.

The closely related common gallinule of the New World has been recognized as a separate species by most authorities,[2] starting with the American Ornithologists' Union and the International Ornithological Committee in 2011.[3]

Name

The name mor-hen has been recorded in English since the 13th century.[4] The word moor here is an old sense meaning marsh;[4] the species is not usually found in moorland. An older name, common waterhen, is more descriptive of the bird's habitat.

A "watercock" is not a male "waterhen" but the rail species Gallicrex cinerea, not closely related to the common moorhen. "Water rail" usually refers to Rallus aquaticus, again not closely related.

The scientific name Gallinula chloropus comes from the Latin Gallinula (a small hen or chicken) and the Greek chloropus (khloros χλωρός green or yellow, pous πούς foot).[5]

Description

The moorhen is a distinctive species, with dark plumage apart from the white undertail, yellow legs and a red frontal shield. The young are browner and lack the red shield. The frontal shield of the adult has a rounded top and fairly parallel sides; the tailward margin of the red unfeathered area is a smooth waving line. In the related common gallinule of the Americas, the frontal shield has a fairly straight top and is less wide towards the bill, giving a marked indentation to the back margin of the red area.

The common moorhen gives a wide range of gargling calls and will emit loud hisses when threatened.[6] A midsized to large rail, it can range from 30 to 38 cm (12 to 15 in) in length and span 50 to 62 cm (20 to 24 in) across the wings. The body mass of this species can range from 192 to 500 g (6.8 to 17.6 oz).[7][8]

Habitat

This is a common breeding bird in marsh environments, well-vegetated lakes and even in city parks. Populations in areas where the waters freeze, such as eastern Europe, will migrate to more temperate climates. In China, common moorhen populations are largely resident south of the Yangtze River, whilst northern populations migrate in the winter, therefore these populations show high genetic diversity. [9]

Behaviour

Diet and feeding

This species will consume a wide variety of vegetable material and small aquatic creatures. They forage beside or in the water, sometimes walking on lilypads or upending in the water to feed. They are often secretive, but can become tame in some areas. Despite loss of habitat in parts of its range, the common moorhen remains plentiful and widespread.

Breeding

The birds are territorial during breeding season. The nest is a basket built on the ground in dense vegetation. Laying starts in spring, between mid-March and mid-May in Northern hemisphere temperate regions. About 8 eggs are usually laid per female early in the season; a brood later in the year usually has only 5–8 or fewer eggs. Nests may be re-used by different females. Incubation lasts about three weeks. Both parents incubate and feed the young. These fledge after 40–50 days, become independent usually a few weeks thereafter, and may raise their first brood the next spring. When threatened, the young may cling to the parents' body, after which the adult birds fly away to safety, carrying their offspring with them.[6][10]

Status and population

On a global scale – all subspecies taken together – the common moorhen is as abundant as its vernacular name implies. It is therefore considered a species of Least Concern by the IUCN.[1] However, small populations may be prone to extinction. The population of Palau, belonging to the widespread subspecies G. c. orientalis and locally known as debar (a generic term also used for ducks and meaning roughly "waterfowl"), is very rare, and apparently the birds are hunted by locals. Most of the population on the archipelago occurs on Angaur and Peleliu, while the species is probably already gone from Koror. In the Lake Ngardok wetlands of Babeldaob, a few dozen still occur, but the total number of common moorhens on Palau is about in the same region as the Guam population: fewer than 100 adult birds (usually fewer than 50) have been encountered in any survey.[11]

The common moorhen is one of the birds (the other is the Eurasian coot, Fulica atra) from which the cyclocoelid flatworm parasite Cyclocoelum mutabile was first described.[12] The bird is also parasitised by the moorhen flea, Dasypsyllus gallinulae.[13]

Subspecies

Five subspecies are today considered valid; several more have been described that are now considered junior synonyms. Most are not very readily recognizable, as differences are rather subtle and often clinal. Usually, the location of a sighting is the most reliable indication as to subspecies identification, but the migratory tendencies of this species make identifications based on location not completely reliable. In addition to the extant subspecies listed below, an undescribed form from the Early Pleistocene is recorded from Dursunlu in Turkey.[14][15][16]

| List of subspecies by date of description | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Common and trinomial names |

Description | Range | |

| Eurasian common moorhen G. c. chloropus (Linnaeus, 1758) Includes correiana and indica. |

.jpg) |

Wings and back blackish-olive | Ranges from Northwest Europe to North Africa and eastwards to Central Siberia and from the humid regions of the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia eastwards to Japan; also found the Canary, Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde islands. |

| Indo-Pacific common moorhen G. c. orientalis (Horsfield, 1821) |

Small, with slate grey upperwing coverts and large frontal shield. | Found in the Seychelles, Andaman Islands, and South Malaysia through Indonesia; also found in the Philippines and Palau. The breeding population existing on Yap in Micronesia since the 1980s is probably of this subspecies, but might be of the rare G. c. guami.[17][18] Population size: Perhaps a few 100s on Palau as of the early 2000s,[11] less than 100 on Yap as of the early 2000s.[17][18] | |

| African common moorhen G. c. meridionalis (C. L. Brehm, 1831) |

|

Similar to orientalis, but the frontal shield is smaller. | Found in Sub-Saharan Africa and Saint Helena. |

| Madagascan common moorhen G. c. pyrrhorrhoa (A. Newton, 1861) |

|

Similar to meridionalis, but the undertail coverts are buff. | Found on the islands of Madagascar, Réunion, Mauritius, and the Comoros. |

| Mariana common moorhen G. c. guami (Hartert, 1917) Called pulattat in Chamorro. |

Body plumage is very dark. | Endemic to the Northern Mariana Islands, but see also G. c. orientalis above. Population size: About 300 as of 2001.[19] | |

Gallery

Common Moorhen chick having a paddle

Common Moorhen chick having a paddle_collecting_for_nest.jpg) collecting for nest, Wolvercote, Oxfordshire

collecting for nest, Wolvercote, Oxfordshire_on_nest.jpg) on nest, Wolvercote, Oxfordshire

on nest, Wolvercote, Oxfordshire Chick, 1–2 weeks old

Chick, 1–2 weeks old Moorhen feeding chick some regurgitated food

Moorhen feeding chick some regurgitated food

_juvenile.jpg) Juvenile, Strumpshaw Fen, Norfolk

Juvenile, Strumpshaw Fen, Norfolk

References

- BirdLife International (2014). "Gallinula chloropus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Common Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus) Linnaeus, 1758". Avibase. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Chesser, R. Terry; Banks, Richard C.; Barker, F. Keith; Cicero, Carla; Dunn, Jon L.; Kratter, Andrew W.; Lovette, Irby J.; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Remsen, J. V.; Rising, James D.; Stotz, Douglas F.; Winker, Kevin (2011). "Fifty-second supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds". Auk. 128 (3): 600–613. doi:10.1525/auk.2011.128.3.600.

- Lockwood, W.B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866196-2.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 103, 170. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Snow, David W.; Perrins, Christopher M.; Doherty, Paul; Cramp, Stanley (1998). The Complete Birds of the Western Palaearctic on CD-ROM. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-268579-1.

- Common moorhen media from ARKive Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- "Common Gallinule". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Ruan, L.; Xu, W.; Han, Y.; Zhu, C.; Guan, B.; Xu, C.; Goa, B.; Zhao, D. (2018). "Gene flow from multiple sources maintains high genetic diversity and stable population history of Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropus in China". Ibis. 160 (4): 855–869. doi:10.1111/ibi.12579.

- Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- VanderWerf, Eric A.; Wiles, Gary J.; Marshall, Ann P.; Knecht, Melia (2006). "Observations of migrants and other birds in Palau, April–May 2005, including the first Micronesian record of a Richard's Pipit". Micronesica. 39 (1): 11–29.

- Dronen, Norman O.; Gardner, Scott L.; Jiménez, F. Agustín (2006). "Selfcoelum limnodromi n. gen., n. sp. (Digenea: Cyclocoelidae: Cyclocoelinae) from the long-billed dowitcher, Limnodromus scolopaceus (Charadriiformes: Scolopacidae) from Oklahoma, U.S.A" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1131: 49–58. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1131.1.3.

- Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1953). Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos. A study of bird parasites. London: Collins. p. 113.

- McCoy, John J. (1963). "The fossil avifauna of Itchtucknee (sic) River, Florida" (PDF). Auk. 80 (3): 335–351. doi:10.2307/4082892. JSTOR 4082892.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1974). "The Pleistocene Rails of North America" (PDF). Condor. 76 (2): 169–175. doi:10.2307/1366727. JSTOR 1366727.

- Louchart, Antoine; Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile; Guleç, Erksin; Howell, Francis Clark; White, Tim D. (1998). "L'avifaune de Dursunlu, Turquie, Pléistocène inférieur: climat, environnement et biogéographie" [The avifauna of Dursunlu, Turkey, Lower Pleistocene: climate, environment and biogeography]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIA (in French). 327 (5): 341–346. doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(98)80053-0.

- Wiles, Gary J.; Worthington, David J.; Beck, Robert E. Jr.; Pratt, H. Douglas; Aguon, Celestino F.; Pyle, Robert L. (2000). "Noteworthy Bird Records for Micronesia, with a Summary of Raptor Sightings in the Mariana Islands, 1988–1999". Micronesica. 32 (2): 257–284.

- Wiles, Gary J.; Johnson, Nathan C.; de Cruz, Justine B.; Dutson, Guy; Camacho, Vicente A.; Kepler, Angela Kay; Vice, Daniel S.; Garrett, Kimball L.; Kessler, Curt C.; Pratt, H. Douglas (2004). "New and Noteworthy Bird Records for Micronesia, 1986–2003". Micronesica. 37 (1): 69–96.

- Takano, Leilani L.; Haig, Susan M. (2004). "Distribution and Abundance of the Mariana Subspecies of the Common Moorhen". Waterbirds. 27 (2): 245–250. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2004)027[0245:DAAOTM]2.0.CO;2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gallinula chloropus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Gallinula chloropus |

- (Common) Moorhen species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- "Common moorhen media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Common Gallinule Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Common Moorhen Information - Gallinula chloropus - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Madeira Birds – Moorhen breeding in Madeira Island

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 5.7 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- BirdLife species factsheet for Gallinula chloropus

- Common moorhen photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Audio recordings of Common moorhen on Xeno-canto.