Clytie (Oceanid)

Clytie (/ˈklaɪtiiː/; Greek: Κλυτίη), or Clytia (/ˈklaɪtiə/; Greek: Κλυτία) was a water nymph, daughter of Oceanus and Tethys in Greek mythology.[1] She loved Helios in vain.[2]

Narrative

Helios, having loved her, abandoned her for Leucothoe and left her deserted. She was so angered by his treatment that she told Leucothea's father, Orchamus, about the affair. Since Helios had defiled Leucothea, Orchamus had her put to death by burial alive in the sands. Clytie intended to win Helios back by taking away his new love, but her actions only hardened his heart against her. She stripped herself and sat naked, with neither food nor drink, for nine days on the rocks, staring at the sun, Helios, and mourning his departure. After nine days she was transformed into the turnsole, also known as heliotrope (which is known for growing on sunny, rocky hillsides),[3] which turns its head always to look longingly at Helios' chariot of the sun. The episode is most fully told in Ovid, Metamorphoses iv. 204, 234–56.

Modern traditions substitute the turnsole with a sunflower, which according to (incorrect) folk wisdom turns in the direction of the sun. The original French form tournesol primarily refers to sunflower, while the English turnsole is primarily used for heliotrope.

Art

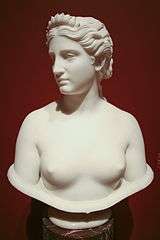

Bust (Townley collection)

One sculpture of Clytie, found in the collection of Charles Townley, might be either a Roman work, or an eighteenth century "fake".[4]

The bust was created between 40 and 50 AD. Townley acquired it from the family of the principe Laurenzano in Naples during his extended second Grand Tour of Italy (1771–1774); the Laurenzano insisted it had been found locally. It remained a favorite both with him (it figures prominently in Johann Zoffany's iconic painting of Townley's library (illustration, right), was one of three ancient marbles Townley had reproduced on his visiting card, and was apocryphally the one which he wished he could carry with him when his house was torched in the Gordon Riots – apocryphal since the bust is in fact far too heavy for that) and with the public (Joseph Nollekens is said to have always had a marble copy of it in stock for his customers to purchase, and in the late 19th century Parian ware copies were all the rage.[5]

The identity of the subject, a woman emerging from a calyx of leaves, was much discussed among the antiquaries in Townley's circle. At first referred to as Agrippina, and later called by Townley Isis in a lotus flower, it is now accepted as Clytie. Some modern scholars even claim the bust is of eighteenth century date, though most now think it is an ancient work showing Antonia Minor or a contemporaneous Roman lady in the guise of Ariadne.

Bust (George Frederick Watts)

Another famous bust of Clytie was by George Frederick Watts.[6] Instead of Townley's serene Clytie, Watts's is straining, looking round at the sun.

References

- Her name appears in the long list of Oceanids in Hesiod, Theogony 346ff.

- Two other minor personages name Clytie are noted: see Theoi Project: Clytie.

- Scholia on in Ovid Metamorphoses 4.267

- Trustees of the British Museum – Marble bust of 'Clytie' Archived 2012-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Trustees of the British Museum – Parian bust of Clytie Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- The Victorian Web – Clytie George Frederick Watts, R.A., 1817–1904

External links

Images of Clytie in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database