Panathenaic Games

The Panathenaic Games (Ancient Greek: Παναθήναια) were held every four years in Athens in Ancient Greece from 566 BC[1] to the 3rd century AD.[2] These Games incorporated religious festival, ceremony (including prize-giving), athletic competitions, and cultural events hosted within a stadium.

In mythology

In the myth of the Minotaur, Minos' son Androgeus is killed during the Panathenaic Games. Some accounts, like Pseudo-Apollodorus's Bibliotheca, state he won and his jealous competitors ambushed and murdered him. Others, such as Graeciae Descriptio by Pausanias, say he was trampled to death by a mad bull.

Religious festival

The competitions for which this festival came to be known were only part of a much larger religious occasion; the Great Panathenaia itself. These ritual observances consisted of numerous sacrifices to Athena (the name-sake of the event and patron deity to the hosts of the event – Athens) as well as Poseidon and others. The Panathenaic festival was formed in order to honor the goddess Athena who had become the patron of Athens after having a competition with the god Poseidon where they were to win the favor of the Athenian people by offering the people gifts. The festival would also bring unity among the people of Athens.[3] A sister-event to the Great Panathenaia was held every year - the Lesser Panathenaia, which was 3–4 days shorter in celebration. The competitions were the most prestigious games for the citizens of Athens, but not as important as the Olympic Games or the other Panhellenic Games.

Ceremony

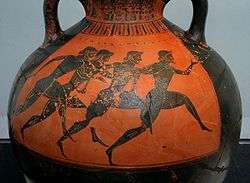

Award ceremonies included the giving of Panathenaic amphorae which were large ceramic vessels containing olive oil given as prizes. The winner of the chariot race received as a prize one-hundred and forty Panathenaic amphorae full of olive oil.

Cultural events

The Panathenaia also included poetic and musical competitions. Prizes were awarded for rhapsodic recitation of Homeric poetry, for instrumental music on the aulus and cithara, and for singing to the accompaniment of the aulus and cithara (citharody). In addition, the Games included a reading of both the Odyssey and the Iliad.

The Panathenaic Stadium

The athletic events were staged at the Panathenaic Stadium, which is still in use today. In 1865, Evangelis Zappas left a vast fortune in his will with instructions to excavate and refurbish the ancient Panathenaic stadium so that modern Olympic Games could be held every four years "in the manner of our ancestors".[4] The Panathenaic stadium has hosted Zappas Olympics in 1870,[5] and 1875, as well as the modern Olympic Games in 1896 and 2004. The stadium also hosted the 1906 Intercalated Games.

Contests

The Panathenaic Games held contests in a number of musical, athletic, and equestrian events. Due to the fact that there were so many contests held, the games usually lasted a little over a week. On a fourth century marble block, experts explain that on the block is written a program for the games, as well as individual events and their prizes. The inscription also says that there are two age categories for the music events but three age categories for the athletic events. According to scholars, the age groups are boys: 12–16; beardless youths: 16–20; men: over 20.[6] One thing that was different about these games than normal funeral games is that prizes were given to runners-up, not just the lone victor.

Using the inscription, experts put together a general program like so: Day 1: Musical and Rhapsodic Contest; Day 2: Athletic Contest for Boys and Youths; Day 3: Athletic Contest for Men; Day 4: Equestrian Contest; Day 5: Tribal Contest; Day 6: Torch Race and Sacrifice; Day 7: Boat Race; Day 8: Awarding of Prizes, Feasting and Celebrations.[6] Experts reasonably came up with how the games went based on the order of prizes which were written on the marble block. Wrestling was also a part of the contest as well as discus.

The musical events which took place were Kithara players, Flute players, and singers. The athletic events were the stadion, pentathlon, wrestling, boxing, and pankration. The equestrian events were two-horse chariot race, horse race, and javelin throw on horseback. Based on the inscription, we learn that the prizes given to the men and the youth were different. Men were rewarded a certain amount of drachmas and/or a valuable crown worth a certain amount of drachmas. Boys and youths were given a certain number of amphoras of olive oil.[6]

References

- A Brief History of the Olympic Games by David C. Young, Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4051-1129-4, p. 23

- Susan Heuck Allen, Finding the walls of Troy: Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann at Hisarlík, University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 0-520-20868-4, p. 39.

- Waldstein, Charles (1885). "The Panathenaic Festival and the Central Slab of the Parthenon Frieze". The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts. 1 (1): 10–17. doi:10.2307/495977. JSTOR 495977.

- The Modern Olympics, A Struggle for Revival by David C. Young, p. 42

- The Modern Olympics, A Struggle for Revival by David C. Young, Chapters 4 & 13

- Neils, Jennifer (1992). Goddess and Polis: The Panathenanic Festival In Ancient Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Further reading

- Roisman, Joseph, and translated by J.C Yardley, Ancient Greece from Homer to Alexander, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2011, ISBN 1-4051-2776-7

- Young, David C., A Brief History of the Olympic Games, Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4051-1129-4