Ring of Gyges

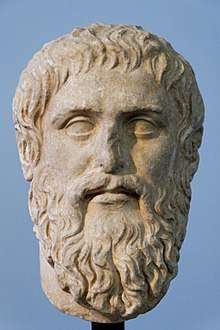

The Ring of Gyges /ˈdʒaɪˌdʒiːz/ (Ancient Greek: Γύγου Δακτύλιος, Gúgou Daktúlios, Attic Greek pronunciation: [ˈɡyːˌɡoː dakˈtylios] is a mythical magical artifact mentioned by the philosopher Plato in Book 2 of his Republic (2:359a–2:360d).[1] It grants its owner the power to become invisible at will. Through the story of the ring, Republic considers whether an intelligent person would be just if one did not have to fear any bad reputation for committing injustices.

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

|

The legends

Gyges of Lydia was a historical king, the founder of the Mermnad dynasty of Lydian kings. Various ancient works—the most well-known being The Histories of Herodotus[2]—gave different accounts of the circumstances of his rise to power.[3] All, however, agree in asserting that he was originally a subordinate of King Candaules of Lydia, that he killed Candaules and seized the throne, and that he had either seduced Candaules' Queen before killing him, married her afterwards, or both.

In Glaucon's recounting of the myth, an unnamed ancestor of Gyges[4] was a shepherd in the service of the ruler of Lydia. After an earthquake, a cave was revealed in a mountainside where he was feeding his flock. Entering the cave, he discovered that it was in fact a tomb with a bronze horse containing a corpse, larger than that of a man, who wore a golden ring, which he pocketed. He discovered that the ring gave him the power to become invisible by adjusting it. He then arranged to be chosen as one of the messengers who reported to the king as to the status of the flocks. Arriving at the palace, he used his new power of invisibility to seduce the queen, and with her help he murdered the king, and became king of Lydia himself.

The role of the legend in Republic

In Republic, the tale of the ring of Gyges is described by the character of Glaucon who is the brother of Plato. Glaucon asks whether any man can be so virtuous that he could resist the temptation of killing, robbing, raping or generally doing injustice to whomever he pleased if he could do so without having to fear detection. Glaucon wants Socrates to argue that it's beneficial for us to be just apart from all considerations of our reputation.

Glaucon posits:

Suppose now that there were two such magic rings, and the just put on one of them and the unjust the other; no man can be imagined to be of such an iron nature that he would stand fast in justice. No man would keep his hands off what was not his own when he could safely take what he liked out of the market, or go into houses and lie with any one at his pleasure, or kill or release from prison whom he would, and in all respects be like a god among men.

Then the actions of the just would be as the actions of the unjust; they would both come at last to the same point. And this we may truly affirm to be a great proof that a man is just, not willingly or because he thinks that justice is any good to him individually, but of necessity, for wherever any one thinks that he can safely be unjust, there he is unjust.

For all men believe in their hearts that injustice is far more profitable to the individual than justice, and he who argues as I have been supposing, will say that they are right. If you could imagine any one obtaining this power of becoming invisible, and never doing any wrong or touching what was another's, he would be thought by the lookers-on to be a most wretched idiot, although they would praise him to one another's faces, and keep up appearances with one another from a fear that they too might suffer injustice.

— Plato, Republic, 360b–d (Jowett trans.)

Though his answer to Glaucon's challenge is delayed, Socrates ultimately argues that justice does not derive from this social construct: the man who abused the power of the Ring of Gyges has in fact enslaved himself to his appetites, while the man who chose not to use it remains rationally in control of himself and is therefore happy (Republic 10:612b).

Cultural influences

- Cicero retells the story of Gyges in De Officiis to illustrate his thesis that a wise or good individual bases decisions on a fear of moral degradation as opposed to punishment or negative consequences. Cicero follows with a discussion of the role of thought experiments in philosophy. The hypothetical situation in question is complete immunity from punishment of the kind afforded to Gyges by his ring.[5]

- In the first canto of Orlando Innamorato, Galafrone, king of Cathay, gives his son Argalia a ring which makes the bearer invisible when carried in one's mouth and which protects against enchantment when worn on one's finger.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his "sixth walk" from his 1782 Reveries of a Solitary Walker (French: Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire), cites the Ring of Gyges legend and contemplates how he would use the ring of invisibility himself.

- Alberich's Ring in the Richard Wagner's opera Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung)

- H. G. Wells' The Invisible Man has as its basis a retelling of the tale of the Ring of Gyges.[6]

- The One Ring from J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings grants invisibility to its wearer but corrupts its owner. Although there is speculation[7] that Tolkien was influenced by Plato's story, a search on "Gyges" and "Plato" in his letters and biography provides no evidence for this. Unlike Plato's ring, Tolkien's exerts an active malevolent force that necessarily destroys the morality of the wearer.[8]

- Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz includes a modified subplot in his novel Arabian Nights and Days.

See also

References

- Laird, A. (2001). "Ringing the Changes on Gyges: Philosophy and the Formation of Fiction in Plato's Republic". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 121: 12–29. doi:10.2307/631825. JSTOR 631825.

- Herodotus 1.7–13

- Smith, Kirby Flower (1902). "The Tale of Gyges and the King of Lydia". American Journal of Philology. 23 (4): 361–387. doi:10.2307/288700. JSTOR 288700.

- Republic 359d: "τῷ [Γύγου] τοῦ Λυδοῦ προγόνῳ". In Republic, Book 10 (Republic 612b), Socrates refers to the ring as "the ring of Gyges" (τὸν Γύγου δακτύλιον). For this reason, the story is simply called "The Ring of Gyges".

- De Officiis 3.38–39

- Holt, Philip (July 1992). "H.G. Wells and the Ring of Gyges". Science Fiction Studies. 19, Part 2 (57): 236–247. JSTOR 4240153.

- "Plato: Ethics - Ring of Gyges". Oregon State University. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- Tolkien, The Lord of the Ring, Book I, Chapter 2, "The Shadow of the Past".

External links

- Glaukon's Challenge Glaukon's speech from book 2, translated by Cathal Woods (2010).

- Plato, Republic Book 2, translated by Benjamin Jowett (1892).

- The Ring of Gyges Analysis by Bernard Suzanne (1996).