John Tzetzes

John Tzetzes (Greek: Ἰωάννης Τζέτζης, romanized: Iōánnēs Tzétzēs; c. 1110, Constantinople – 1180, Constantinople) was a Byzantine poet and grammarian who is known to have lived at Constantinople in the 12th century.

He was able to preserve much valuable information from ancient Greek literature and scholarship.[1]

Biography

Tzetzes was Greek on his father's side and part Iberian (Georgian) on his mother's side.[2] In his works, Tzetzes states that his grandmother was a relative of the Georgian Bagratid princess Maria of Alania who came to Constantinople with her and later became the second wife of the sebastos Constantine Keroularios, megas droungarios and nephew of the patriarch Michael Keroularios.[3]

He worked as a secretary to a provincial governor for a time and later began to earn a living by teaching and writing.[1] He was described as vain, seems to have resented any attempt at rivalry, and violently attacked his fellow grammarians. Owing to a lack of written material, he was obliged to trust to his memory; therefore caution has to be exercised in reading his work. However, he was learned, and made a great contribution to the furtherance of the study of ancient Greek literature.

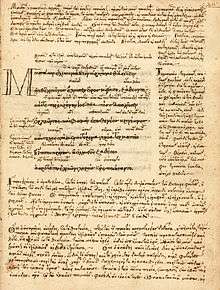

The most important of his many works is considered to be the Book of Histories, usually called Chiliades ("thousands") from the arbitrary division by its first editor (N. Gerbel, 1546) into books each containing 1000 lines (it actually consists of 12,674 lines of political verse). It is a collection of literary, historical, theological, and antiquarian miscellanies, whose chief value consists in the fact that it, to some extent, makes up for the loss of works which were then accessible to Tzetzes. The whole production suffers from an unnecessary display of learning, with the total number of authors quoted being more than 200.[4] The author subsequently brought out a revised edition with marginal notes in prose and verse (ed. T. Kiessling, 1826; on the sources see C. Harder, De J. T. historiarum fontibus quaestiones selectae, diss., Kiel, 1886).[5]

His collection of 107 Letters addressed partly to fictitious personages, and partly to the great men and women of the writer's time, contain a considerable amount of biographical details.

Tzetzes supplemented Homer's Iliad by a work that begins with the birth of Paris and continues the tale to the Achaeans' return home.

The Homeric Allegories, in "political" verse and dedicated initially to the German-born empress Irene and then to Constantine Cotertzes,[5] are two didactic poems, the first based on the Iliad and the second based on the Odyssey, in which Homer and the Homeric theology are set forth and then explained by means of three kinds of allegory: euhemeristic (πρακτική), anagogic (ψυχική) and physic (στοιχειακή). The first of these works was translated into English in 2015 by Adam J. Goldwyn and Dimitra Kokkini.[6]

In the Antehomerica, Tzetzes recalls the events taking place before Homer's Iliad. This work was followed by the Homerica, covering the events of the Iliad, and the Posthomerica, reporting the events taking place between the Iliad and the Odyssey. All three are currently available in English translations.

Tzetzes also wrote commentaries on a number of Greek authors, the most important of which is that elucidating the obscure Cassandra or Alexandra of the Hellenistic poet Lycophron, usually called "On Lycophron" (edited by K.O. Müller, 1811), in the production of which his brother Isaac is generally associated with him. Mention may also be made of a dramatic sketch in iambic verse, in which the caprices of fortune and the wretched lot of the learned are described; and of an iambic poem on the death of the emperor Manuel I Komnenos, noticeable for introducing at the beginning of each line the last word of the line preceding it (both in Pietro Matranga, Anecdota Graeca 1850).

For the other works of Tzetzes see J. A. Fabricius, Bibliotheca graeca (ed. Harles), xi.228, and Karl Krumbacher, Geschichte der byz. Litt. (2nd ed., 1897); monograph by G. Hart, "De Tzetzarum nomine, vitis, scriptis," in Jahn's Jahrbucher für classische Philologie. Supplementband xii (Leipzig, 1881).[5]

References

- "John Tzetzes - Byzantine scholar".

- Banani, Amin (1977). Individualism and Conformity in Classical Islam. Otto Harrassowitz. p. 126. ISBN 9783447017824.

In the twelfth century, John Tzetzes writes to a member of the imperial family: "I descend from the most noble of Iberians in my mother's family; from my father I am a pure Greek."

- Garland, Lynda (2006), Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience, 800-1200, pp. 95-6. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-5737-X.

- Abrantes 2017.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Tzetzes, John. Allegories of the Iliad. Trans. Adam J. Goldwyn and Dimitra Kokkini. Harvard University Press.

Sources

- Abrantes, Miguel Carvalho (2017), Sources of Tzetzes Chiliades: Second Edition. CreateSpace.

- (in French) Gautier, Paul (1970), La curieuse ascendance de Jean Tzetzes. Revue des Études Byzantines, 28: 207-20.

- Goldwyn, Adam, Kokkini, Dimitra (2015), Allegories of the Iliad. Harvard University Press.

External links

- Tzetzes Allegoriae Iliadis 1851 edition at Internet Archive

- Scolia eis Lycophroon, 1811 edition at Google Books

- Tzetzes, Letters 1851 edition at Internet Archive

- Ioannis Tzetzae Antehomerica, Homerica et posthomerica 1793 edition at Google Books

- English translations of Tzetzes' Antehomerica, Homerica and Posthomerica

- English translation of Tzetzes' Chiliades

- Chiliades 1826 edition at Google Books