Libation

A libation is a ritual pouring of a liquid, or grains such as rice, as an offering to a deity or spirit, or in memory of the dead. It was common in many religions of antiquity and continues to be offered in cultures today.

Various substances have been used for libations, most commonly wine or other alcoholic drinks, olive oil, honey, and in India, ghee. The vessels used in the ritual, including the patera, often had a significant form which differentiated them from secular vessels. The libation could be poured onto something of religious significance, such as an altar, or into the earth.

In East Asia, pouring an offering of rice into a running stream, symbolizes the unattachment from karma and bad energy.

Religious practice

Historical

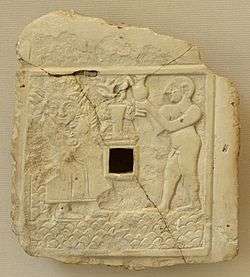

Ancient Sumer

The Sumerian afterlife was a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground,[1][2] This bleak domain was known as Kur,[1][3]:114[4]:184 the souls in there were believed to eat nothing but dry dust[3]:58 and family members of the deceased would ritually pour libations into the dead person's grave through a clay pipe, thereby allowing the dead to drink.[3]:58

Ancient Egypt

Libation was part of ancient Egyptian society where it was a drink offering to honor and please the various divinities, sacred ancestors, humans present and not present, as well as the environment. It is suggested that libation originated somewhere in the upper Nile Valley and spread out to other regions of Africa and the world.[5][6] According to Ayi Kwei Armah, “[t]his legend explains the rise of a propitiatory custom found everywhere on the African continent: libation, the pouring of alcohol or other drinks as offerings to ancestors and divinities.”[7]

Ancient Israel

Libations were part of ancient Judaism and are mentioned in the Bible:[8]

And Jacob set up a Pillar in the place where he had spoken with him, a Pillar of Stone; and he poured out a drink offering on it, and poured oil on it.

— Genesis 35:14

In Isaiah 53:12, Isaiah uses libation as a metaphor when describing the end of the Suffering Servant figure who "poured out his life unto death".

Ancient Greece

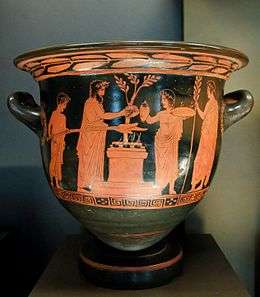

Libation (Greek: σπονδή, spondȇ, [spondɛ̌ː]) was a central and vital aspect of ancient Greek religion, and one of the simplest and most common forms of religious practice.[9] It is one of the basic religious acts that define piety in ancient Greece, dating back to the Bronze Age and even prehistoric Greece.[10] Libations were a part of daily life, and the pious might perform them every day in the morning and evening, as well as to begin meals.[11] A libation most often consisted of mixed wine and water, but could also be unmixed wine, honey, oil, water, or milk.[12]

The typical form of libation, spondȇ, is the ritualized pouring of wine from a jug or bowl held in the hand. The most common ritual was to pour the liquid from an oinochoē (wine jug) into a phiale, a shallow bowl designed for the purpose. After wine was poured from the phiale, the remainder of the oinochoē's contents was drunk by the celebrant.[13] A libation is poured any time wine is to be drunk, a practice that is recorded as early as the Homeric epics. The etiquette of the symposium required that when the first bowl (krater) of wine was served, a libation was made to Zeus and the Olympian gods. Heroes received a libation from the second krater served, and Zeús Téleios (Ζεύς Tέλειος, lit. "Zeus who Finishes") from the third, which was supposed to be the last. An alternative was to offer a libation from the first bowl to the Agathos Daimon and from the third bowl to Hermes. An individual at the symposium could also make an invocation of and libation to a god of his choice.

Libation generally accompanied prayer.[14] The Greeks stood when they prayed, either with their arms uplifted, or in the act of libation with the right arm extended to hold the phiale.[15]

In conducting animal sacrifice, wine is poured onto the victim as part of its ritual slaughter and preparation, and then afterwards onto the ash and flames.[16] This scene is commonly depicted in Greek art, which also often shows sacrificers or the gods themselves holding the phiale.[17]

The Greek verb spéndō (σπένδω), "pour a libation", also "conclude a pact", derives from the Indo-European root *spend-, "make an offering, perform a rite, engage oneself by a ritual act". The noun is spondȇ (plural spondaí), "libation." In the middle voice, the verb means "enter into an agreement", in the sense that the gods are called to guarantee an action.[18] Blood sacrifice was performed to begin a war; spondaí marked the conclusion of hostilities, and is often thus used in the sense of "armistice, treaty." The formula "We the polis have made libation" was a declaration of peace or the "Truce of God", which was observed also when the various city-states came together for the Panhellenic Games, the Olympic Games, or the festivals of the Eleusinian Mysteries: this form of libation is "bloodless, gentle, irrevocable, and final".[17]

Libations poured onto the earth are meant for the dead and for the chthonic gods. In the Book of the Dead in the Odyssey, Odysseus digs an offering pit around which he pours in order honey, wine, and water. For the form of libation called choē (Ancient Greek: χεῦμα, cheuma, "that which is poured"; from IE *gheu-),[19] a larger vessel is tipped over and emptied onto the ground for the chthonic gods, who may also receive spondai.[20] Heroes, who were divinized mortals, might receive blood libations if they had participated in the bloodshed of war, as for instance Brasidas the Spartan.[21] In rituals of caring for the dead at their tombs, libations would include milk and honey.[22]

The Libation Bearers is the English title of the center tragedy from the Orestes Trilogy of Aeschylus, in reference to the offerings Electra brings to the tomb of her dead father Agamemnon.[17] Sophocles gives one of the most detailed descriptions of libation in Greek literature in Oedipus at Colonus, performed as atonement in the grove of the Eumenides:

First, water is fetched from a freshly flowing spring; cauldrons which stand in the sanctuary are garlanded with wool and filled with water and honey; turning towards the east, the sacrificer tips the vessels towards the west; the olive branches which he has been holding in his hand he now strews on the ground at the place where the earth has drunk in the libation; and with a silent prayer he departs, not looking back.[23]

Hero of Alexandria described a mechanism for automating the process by using altar fires to force oil from the cups of two statues.

Ancient Rome

.jpg)

The English word "libation" derives from the Latin libatio, an act of pouring, from the verb libare, "to taste, sip; pour out, make a libation" (Indo-European root *leib-, "pour, make a libation").[24] In ancient Roman religion, the libation was an act of worship in the form of a liquid offering, most often unmixed wine and perfumed oil.[25] The Roman god Liber Pater ("Father Liber"), later identified with the Greek Dionysus or Bacchus, was the divinity of libamina, "libations," and liba, sacrificial cakes drizzled with honey.[26]

In Roman art, the libation is shown performed at a mensa (sacrificial meal table), or tripod. It was the simplest form of sacrifice, and could be a sufficient offering by itself.[27] The introductory rite (praefatio) to an animal sacrifice included an incense and wine libation onto a burning altar.[28] Both emperors and divinities are frequently depicted, especially on coins, pouring libations.[29] Scenes of libation commonly signify the quality of pietas, religious duty or reverence.[30]

The libation was part of Roman funeral rites, and may have been the only sacrificial offering at humble funerals.[31] Libations were poured in rituals of caring for the dead (see Parentalia and Caristia), and some tombs were equipped with tubes through which the offerings could be directed to the underground dead.[32]

Milk was unusual as a libation at Rome, but was regularly offered to a few deities, particularly those of an archaic nature[33] or those for whom it was a natural complement, such as Rumina, a goddess of birth and childrearing who promoted the flow of breast milk, and Cunina, a tutelary of the cradle.[34] It was offered also to Mercurius Sobrius (the "sober" Mercury), whose cult is well attested in Roman Africa and may have been imported to the city of Rome by an African community.[35]

Africa

Ancient Egypt

Libation was part of ancient Egyptian society where it was a drink offering to honor and please the various divinities, sacred ancestors, humans present and not present, as well as the environment. It is suggested that libation originated somewhere in the upper Nile Valley and spread out to other regions of Africa and the world.[5][6] According to Ayi Kwei Armah, “[t]his legend explains the rise of a propitiatory custom found everywhere on the African continent: libation, the pouring of alcohol or other drinks as offerings to ancestors and divinities.”[7]

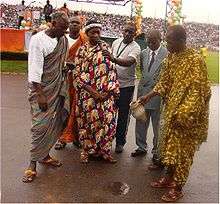

In African cultures, African traditional religions the ritual of pouring libation is an essential ceremonial tradition and a way of giving homage to the ancestors. Ancestors are not only respected in such cultures, but also invited to participate in all public functions (as are also the gods and God). A prayer is offered in the form of libations, calling the ancestors to attend. The ritual is generally performed by an elder. Although water may be used, the drink is typically some traditional wine (e.g. palm wine), and the libation ritual is accompanied by an invitation (and invocation) to the ancestors, gods and God. In the Volta region of Ghana, water with a mixture of corn flour is also used to pour libation.

Libation is also commonly recognized as the break within the famous performance of Agbekor, a ritual dance performed in West African cultures. It is also poured during traditional marriage ceremony, when a child is born and funeral ceremony. Traditional Festivals like Asafotu and Homowo of the Ga Adangbe people of Ghana and Togo. Also during installment of Kings, Queens, Chiefs libation is poured.

Americas

In the Quechua and Aymara cultures of the South American Andes, it is common to pour a small amount of one's beverage on the ground before drinking as an offering to the Pachamama, or Mother Earth. This especially holds true when drinking Chicha, an alcoholic beverage unique to this part of the world. The libation ritual is commonly called challa and is performed quite often, usually before meals and during celebrations. The sixteenth century writer Bernardino de Sahagún records the Aztec ceremony associated with drinking octli:

Libation was done in this manner: when octli was drunk, when they tasted the new octli, when someone had just made octli...he summoned people. He set it out in a vessel before the hearth, along with small cups for drinking. Before having anyone drink, he took up octli with a cup and then poured it before the hearth; he poured the octli in the four directions. And when he had poured the octli then everyone drank it.[36]

Asia

Burmese Buddhism

In Burmese Buddhism, the water libation ceremony, called yay zet cha (ရေစက်ချ), which involves the ceremonial pouring of water from a vessel of water into a vase, drop by drop, concludes most Buddhist ceremonies, including donation celebrations, shinbyu, and feasts. This ceremonial libation is done to share the accrued merit with all other living beings in all 31 planes of existence.[37] The ceremony has three primary prayers: the confession of faith, the pouring of water, and the sharing of merits.[38] While the water is poured, a confession of faith, called the hsu taung imaya dhammanu (ဆုတောင်း ဣမာယ ဓမ္မာနု), is recited and led by the monks.[39]

Then, the merit is distributed by the donors (called ahmya wei အမျှဝေ) by thrice saying the following:[38]

(To all those who can hear), we share our merits with all beings

(Kya kya thahmya), ahmya ahmya ahmya yu daw mu gya ba gon law''

((ကြားကြားသမျှ) အမျှ အမျှ အမျှ ယူတော်မူကြပါ ကုန်လော)

Afterward, in unison, the participants repeat thrice a declaration of affirmation: thadu (သာဓု, sadhu), Pali for "well done", akin to the Christian use of amen. Afterward, the libated water is poured on soil outside, to return the water to Vasudhara. The earth goddess Vasudhara is invoked to witness these meritorious deeds.[39]

Prior to colonial rule, the water libation ceremony was also performed during the crowning of Burmese kings, as part of procedures written in the Raza Thewaka Dipani Kyan, an 1849 text that outlines proper conduct of Burmese kings.[40][41]

Although the offering of water to Vasudhara may have pre-Buddhist roots, this ceremony is believed to have been started by King Bimbisara, who poured the libation of water, to share his merit with his ancestors who had become pretas.[42][43][44]

This ceremony is also practiced at the end of Thai and Laotian Buddhist rituals to transfer merit, where it is called kruat nam (กรวดน้ำ) and yaat nam respectively.[45]

Hinduism

In Hinduism the ritual is part of Tarpan and also performed during Pitru Paksha (Fortnight of the ancestors) following the Bhadrapada month of the Hindu calendar, (September–October).[46] In India and Nepal, Lord Shiva (also Vishnu and other deities) is offered abhiṣeka with water by devotees at many temples when they go visit the temple, and on special occasions elaborately with water, milk, yogurt, ghee, honey, and sugar.

China

In Chinese customs, rice wine or tea is poured in front of an altar or tombstone horizontally from right to left with both hands as an offering to gods and in honour of deceased. The offering is usually placed on the altar for a while before being offered in libation. In more elaborate ceremonies honouring deities, the libation may be done over the burning paper offerings; whereas for the deceased, the wine is only poured onto the ground.

Japan

In Shinto, the practice of libation and the drink offered is called Miki (神酒), lit. "The Liquor of the Gods". At a ceremony at a Shinto shrine, it is usually done with sake, but at a household shrine, one may substitute fresh water which can be changed every morning. It is served in a white porcelain or metal cup without any decoration.

Siberian shamanism

Shamanism among Siberian peoples exhibits the great diversity characteristic of shamanism in general.[47] Among several peoples near the Altai Mountains, the new drum of a shaman must go through a special ritual. This is regarded as "enlivening the drum": the tree and the deer who gave their wood and skin for the new drum narrate their whole lives and promise to the shaman that they will serve him. The ritual itself is a libation: beer is poured onto the skin and wood of the drum, and these materials "come to life" and speak with the voice of the shaman in the name of the tree and the deer. Among the Tubalar, moreover, the shaman imitates the voice of the animal, and its behaviour as well.[48]

Modern customs

In Cuba a widespread custom is to spill a drop or two of rum from one's glass while saying "para los santos" (‘for the Saints’). An identical form is done in Brazil when one drinks cachaça, with the drops being offered "para o santo" or "para o santinho". These customs are similar to the practise of Visayans living on Mindanao, the Philippines, where they spill a capful of rum as soon as the bottle is opened while saying "para sa yawa" ('for the Devil').[49]

In Russia and surrounding countries, it is an old tradition to pour vodka onto a grave, an act possibly connected with dziady custom.

In the contemporary United States, occasionally libations are offered in the name of a deceased person on various occasions, usually when drinking socially among friends in a private setting. There is also a tradition of pouring libations of malt liquor from a forty before drinking, which is particularly associated with African-American rappers. This is referred to as "tipping" to one's [dead] homies (friends),[50] or "pouring one out".[51] This is performed in movies, such as Boyz n the Hood, and referenced in various songs, such as the 1993 "Gangsta Lean (This Is For My Homies)" by DRS ("I tip my 40 to your memory"), and sometimes accompanied by ritual expressions such as "One for me, and one for my homies" as well as the 1994 song "Pour Out a Little Liquor" by 2Pac. This was parodied in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999).[52]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Libations. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Libation |

| Look up libation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Notes

- Choksi, M. (2014), "Ancient Mesopotamian Beliefs in the Afterlife", Ancient History Encyclopedia, ancient.eu

- Barret, C. E. (2007). "Was dust their food and clay their bread?: Grave goods, the Mesopotamian afterlife, and the liminal role of Inana/Ištar". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. 7 (1): 7–65. doi:10.1163/156921207781375123. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-1705-6

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998), Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Daily Life, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0313294976

- Delia, 1992, pp. 181-190

- James, George G. M. (1954) Stolen Legacy, New York: Philosophical Library

- Armah, Ayi Kwei (2006) The Eloquence of the Scribes: a memoir on the sources and resources of African literature. Popenguine, Senegal: Per Ankh, p207

- Bar, Shaul (2016). A Nation Is Born: The Jacob Story. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4982-3935-6. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Louise Bruit Zaidman and Pauline Schmitt Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, translated by Paul Cartledge (Cambridge University Press, 1992, 2002, originally published 1989 in French), p. 28.

- Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Harvard University Press, 1985, originally published 1977 in German), pp. 70, 73.

- Hesiod, Works and Days 724–726; Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 39.

- Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 40; Burkert, Greek Religion, pp. 72–73.

- Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 40.

- Burkert, Greek Religion, pp. 70–71.

- William D. Furley, "Prayers and Hymns," in A Companion to Greek Religion (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 127; Jan N. Bremmer, "Greek Normative Animal Sacrifice," p. 138 in the same volume.

- Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 36; Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 71.

- Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 71.

- D.Q. Adams and J.P. Mallory, entry on "Libation," in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (Taylor & Francis, 1997), p. 351. From the same root derives the Latin verb spondeo, "promise, vow."

- Adams and Mallory, "Libation," p. 351.

- Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 70.

- Gunnel Ekroth, "Heroes and Hero-Cult," in A Companion to Greek Religion, p. 107.

- D. Felton, "The Dead," in A Companion to Greek Religion, p. 88.

- Summary by Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 72.

- D.Q. Adams and J.P. Mallory, entry on "Libation," in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (Taylor & Francis, 1997), p. 351.

- John Scheid, "Sacrifices for Gods and Ancestors," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 269.

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologies 6.19.32; Adams and Mallory, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, p. 351; . Robert Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome (Routledge, 2001; originally published in French 1998), p. 66.

- Katja Moede, "Reliefs, Public and Private," in A Companion to Roman Religion, pp. 165, 168.

- Moede, "Reliefs, Public and Private," pp. 165, 168; Nicole Belayche, "Religious Actors in Daily Life: Practices and Related Beliefs," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 280.

- Jonathan Williams, "Religion and Roman Coins," in A Companion to Roman Religion, pp. 153–154.

- Scheid, "Sacrifices for Gods and Ancestors," p. 265.

- Scheid, "Sacrifices for Gods and Ancestors," p. 270–271.

- Nicola Denzey Lewis, entry on "Catacombs," The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), vol. 1, p. 58; John R. Clarke, Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 315 (University of California Press, 2003), p. 197.

- Such as Jupiter Latiaris and Pales.

- Hendrik H.J. Brouwer, Bona Dea: The Sources and a Description of the Cult (Brill, 1989), pp. 328–329.

- Robert E.A. Palmer, Rome and Carthage at Peace (Franz Steiner, 1997), pp. 80–81, 86–88.

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Henry B. Nicholson, Thelma D. Sullivan, Primeros Memoriales. The civilization of the American Indian series, University of Oklahoma Press, 1997; p. 72. ISBN 0806129093

- Spiro, Melford E. (1996). Burmese supernaturalism. Transaction Publishers. pp. 44–47. ISBN 978-1-56000-882-8.

- ဝတ်ရွတ်စဉ် (PDF) (in Burmese). Austin, Texas: သီတဂူဗုဒ္ဓဝိဟာရ. 2011. pp. 34–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- Spiro, Melford E. (1982). Buddhism and society: a great tradition and its Burmese vicissitudes. University of California Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-520-04672-6.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-25. Retrieved 2010-06-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.ari.nus.edu.sg/showfile.asp?eventfileid=304

- Houtman, Gustaaf (1990). Traditions of Buddhist Practice in Burma. ILCAA. pp. 53–55.

- http://www.usamyanmar.net/.../Life%20of%20Gotama%20Buddha.ppt%5B%5D

- "The king performs merit in the name of his ancestors reborn as petas (hungry ghosts); the peta rejoice in the act and receive a share of the merit". Mahidol University. 2002. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Hayashi, Yukio (2003). Practical Buddhism among the Thai-Lao: religion in the making of a region. Trans Pacific Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-4-87698-454-1.

- "Indian Hindu devotee performs "Tarpan",". Hindustan Times. Oct 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-12-15. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- Hoppál 2005: 15

- Eliade 2001: 164 (= Chpt 5 discussing the symbolics of shamanic drum and costume, the subsection about the drum)

- Soy del Caribe - Edición No.23 - Reportaje | El Ron de Cuba, con su toque de siglos Archived 2012-09-13 at Archive.today

- "40ozMaltLiquor.com". Archived from the original on 2010-03-07. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- Libation For The Dead, TV Tropes

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0145660/characters/nm0000196

References

- Eliade, Mircea (1983). Le chamanisme et les techniques archaïques de'l extase. Paris: Éditions Payot.

- Eliade, Mircea (2001). A samanizmus. Az extázis ősi technikái. Osiris könyvtár (in Hungarian). Budapest: Osiris. ISBN 963-379-755-1. Translated from Eliade 1983.

- Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3. The title means "Shamans in Eurasia", the book is published also in German, Estonian and Finnish. Site of publisher with short description on the book (in Hungarian).