Sciron

In Greek mythology, Sciron, also Sceiron, Skeirôn and Scyron, (Ancient Greek: Σκίρων; gen.: Σκίρωνoς) was one of the malefactors killed by Theseus on the way from Troezen to Athens. He was a famous Corinthian bandit who haunted the frontier between Attica and Megaris.

Family

Sciron was the son of either Pelops[1] and possibly Hippodameia, or Poseidon[1] and Iphimedeia.[2] Other sources makes his parents as Canethus and Henioche, a daughter of Pittheus which made him a cousin of Theseus.[3] Sciron was also called the son of Pylas, king of Megara and thus great grandson of Lelex.[4] He was the father of Endeis[5] by the daughter of Pandion[4] or Chariclo, daughter of Cychreus.[6] Through his daughter Endeis, Sciron was thus the grandfather of the heroes Telamon and Peleus.[5] A son of Sciron named Alycus, in the army of the Dioscuri was also said to be slain by Theseus when the latter kidnapped the young Helen.[3]

| Relation | Names | Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apollodorus | Plutarch | Pausanias | ||

| Parents | Pelops | ✓ | ||

| Poseidon | ✓ | |||

| Canethus and Henioche | ✓ | |||

| Pylas | ✓ | |||

| Wife | Chariclo | ✓ | ||

| Pandion's daughter | ✓ | |||

| Children | Endeis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alycus | ✓ | |||

Mythology

Sciron, the robber

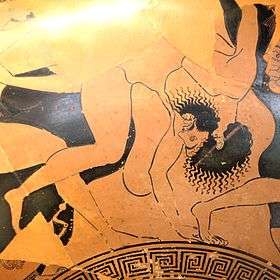

An Isthmian outlaw, Sciron dwelt at the Sceironian Rocks, a cliff on the Saronic coast of the Isthmus of Corinth on the Megarian territory.[2][7] He robbed travelers passing the Sceironian Rocks and sitting near the sea he made it his practice to force them to wash his feet at a precipitous place. When they knelt before him, he would suddenly give them a kick over the cliff into the sea, where the victim's body was devoured by a huge monstrous sea turtle which used to swim under the rocks[2][8] or rolled down the crags into the sea at a place called Chelone (i.e. tortoise).[9] As his fourth labour, Theseus slew him in the same way, by pushing him off the cliff[10] or according to some, the hero seized him by the feet and threw him into the sea.[11][12] In the pediment of the royal Stoa at Athens, there was a group of figures of burnt clay, representing Theseus in the act of throwing Sciron into the sea.[13]

Sciron, the warlord

According to Plutarch, however, the Megarians claimed that Sciron was not a robber, but identified him with the Megarian warlord named Sciron.

"Sciron was neither a violent man nor a robber, but a chastiser of robbers, and a kinsman and friend of good and just men. For Aeacus, they say, is regarded as the most righteous of Hellenes, and Cychreus the Salaminian has divine honors at Athens, and the virtues of Peleus and Telamon are known to all men. Well, then, Sciron was a son-in law of Cychreus, father-in law of Aeacus, and grandfather of Peleus and Telamon, who were the sons of Endeis, daughter of Sciron and Chariclo. It is not likely, then, they say, that the best of men made family alliances with the basest, receiving and giving the greatest and most valuable pledges."[14]

When Pylas was exiled from Megara, he gave the rule to his son-in-law Pandion, who then gave it to his son Nisus. Sciron who married the daughter of Pandion disputed with Nisus about the throne. But later on, he agreed to accept the arbitration of Aeacus, king of Aegina, who decided that Nisus and his descendants should be king and have the government while Sciron was entitled as the military leader and in command of war.[15] Sciron accepted this decision and married his daughter Endeïs to the chosen umpire Aeacus.

In one version, Theseus instituted the Isthmian Games so as to honor him and made expiation for his murder because of their kinship (they were cousins as their mothers Aethra and Henioche were sisters). Others, Plutarch remarked, related the same of Sinis, another bandit killed by Theseus.[3]

A passage in Ovid (Met. 7.444), where the poet claims that certain cliffs by the name of Sciron owe their name to the man, suggests an aetiological origin for the tale.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sciron. |

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, Epitome 1.2

- Tripp, Edward. The Meridian Handbook of Classical Mythology. Meridian, 1970, p. 522.

- Plutarch. Parallel Lives, "Theseus", 25.4-5

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.39.6

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, Book 3.12.6

- Plutarch. Parallel Lives, "Theseus", 10.3

- Strabo. Geography, 9.1.4

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.44.8

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, Book 4.59.4

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, Epitome 1.2; Hyginus. Fabulae, 38; Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.44.12; Scholia. ad Euripides, Hippolytus, 976

- Ovid. Metamorphoses, Book 7.445

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, Epitome 1.3

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.3.1

- Plutarch. Parallel Lives, "Theseus", 10.2-3

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.39.6; 1.44.6

Sources

- William Smith. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, s.v. Sciron 1 & 2. London.