Amphitrite

In ancient Greek mythology, Amphitrite (/æmfɪˈtraɪtiː/; Greek: Ἀμφιτρίτη) was a sea goddess and wife of Poseidon and the queen of the sea.[1] She was a daughter of Doris and Nereus (or Oceanus and Tethys).[2] Under the influence of the Olympian pantheon, she became the consort of Poseidon and was later used as a symbolic representation of the sea and the goddess of the calm seas and safe passage through the storms. It is said that her voice is the only thing that can calm her husband’s mightiest of rages and lull him to a deep slumber so as to bring the ocean to peace once more. In Roman mythology, the consort of Neptune, a comparatively minor figure, was Salacia, the goddess of saltwater.[3]

Mythology

Amphitrite was a daughter of Nereus and Doris (and thus a Nereid), according to Hesiod's Theogony, but of Oceanus and Tethys (and thus an Oceanid), according to the Bibliotheca, which actually lists her among both the Nereids[4] and the Oceanids.[5] Others called her the personification of the sea itself (saltwater). Amphitrite's offspring included seals[6] and dolphins.[7] She also bred sea monsters and her great waves crashed against the rocks, putting sailors at risk.[2] Poseidon and Amphitrite had a son, Triton who was a merman, and a daughter, Rhodos (if this Rhodos was not actually fathered by Poseidon on Halia or was not the daughter of Asopus as others claim). Bibliotheca (3.15.4) also mentions a daughter of Poseidon and Amphitrite named Benthesikyme.

Amphitrite is not fully personified in the Homeric epics: "out on the open sea, in Amphitrite's breakers" (Odyssey iii.101), "moaning Amphitrite" nourishes fishes "in numbers past all counting" (Odyssey xii.119). She shares her Homeric epithet Halosydne ("sea-nourished")[9] with Thetis[10] in some sense the sea-nymphs are doublets.

Representation and cult

Though Amphitrite does not figure in Greek cultus, at an archaic stage she was of outstanding importance, for in the Homeric Hymn to Delian Apollo, she appears at the birthing of Apollo among, in Hugh G. Evelyn-White's translation, "all the chiefest of the goddesses, Dione and Rhea and Ichnaea and Themis and loud-moaning Amphitrite;" more recent translators[11] are unanimous in rendering "Ichnaean Themis" rather than treating "Ichnae" as a separate identity. Theseus in the submarine halls of his father Poseidon saw the daughters of Nereus dancing with liquid feet, and "august, ox-eyed Amphitrite", who wreathed him with her wedding wreath, according to a fragment of Bacchylides. Jane Ellen Harrison recognized in the poetic treatment an authentic echo of Amphitrite's early importance: "It would have been much simpler for Poseidon to recognize his own son... the myth belongs to that early stratum of mythology when Poseidon was not yet god of the sea, or, at least, no-wise supreme there—Amphitrite and the Nereids ruled there, with their servants the Tritons. Even so late as the Iliad Amphitrite is not yet 'Neptuni uxor'" [Neptune's wife]".[12]

.jpg)

Amphitrite, "the third one who encircles [the sea]",[13] was so entirely confined in her authority to the sea and the creatures in it that she was almost never associated with her husband, either for purposes of worship or in works of art, except when he was to be distinctly regarded as the god who controlled the sea. An exception may be the cult image of Amphitrite that Pausanias saw in the temple of Poseidon at the Isthmus of Corinth (ii.1.7).

Pindar, in his sixth Olympian Ode, recognized Poseidon's role as "great god of the sea, husband of Amphitrite, goddess of the golden spindle." For later poets, Amphitrite became simply a metaphor for the sea: Euripides, in Cyclops (702) and Ovid, Metamorphoses, (i.14).

Eustathius said that Poseidon first saw her dancing at Naxos among the other Nereids,[14] and carried her off.[15] But in another version of the myth, she fled from his advances to Atlas,[16] at the farthest ends of the sea; there the dolphin of Poseidon sought her through the islands of the sea, and finding her, spoke persuasively on behalf of Poseidon, if we may believe Hyginus[17] and was rewarded by being placed among the stars as the constellation Delphinus.[18]

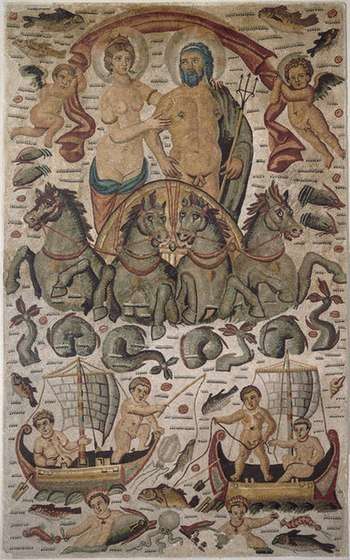

In the arts of vase-painting and mosaic, Amphitrite was distinguishable from the other Nereids only by her queenly attributes. In works of art, both ancient ones and post-Renaissance paintings, Amphitrite is represented either enthroned beside Poseidon or driving with him in a chariot drawn by sea-horses (hippocamps) or other fabulous creatures of the deep, and attended by Tritons and Nereids. She is dressed in queenly robes and has nets in her hair. The pincers of a crab are sometimes shown attached to her temples.

Theseus and Amphitrite clasp hands, with Athena looking on (red-figure cup by Euphronios and Onesimos, 500-490 BC)

Theseus and Amphitrite clasp hands, with Athena looking on (red-figure cup by Euphronios and Onesimos, 500-490 BC) Neptune and Amphitrite by Jacob de Gheyn II (latter 16th-century)

Neptune and Amphitrite by Jacob de Gheyn II (latter 16th-century) The Triumph of Neptune by Nicolas Poussin, showing Amphitrite velificans (1634)

The Triumph of Neptune by Nicolas Poussin, showing Amphitrite velificans (1634) Amphitrite with downturned trident, by François Théodore Devaulx (1866)

Amphitrite with downturned trident, by François Théodore Devaulx (1866)

Amphitrite legacy

- Amphitrite is the name of a genus of the worm family Terebellidae.

- In poetry, Amphitrite's name is often used for the sea, as a synonym of Thalassa.

- Seven ships of the Royal Navy were named HMS Amphitrite

- Amphitrite (1802 ship), which wrecked in 1833 with heavy loss of life while transporting convicts to New South Wales

- At least one ship of the Royal Netherlands Navy was named HM Amphitrite (corvette, in service 1830s).

- Three ships of the United States Navy were named USS Amphitrite.

- An asteroid, 29 Amphitrite, is named for her.

- The figure of Amphitrite plays a role in the 1918 Spanish novel Mare Nostrum by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez and its 1926 film adaptation.

- In 1936 Australia used an image of Amphitrite on a postage stamp as a classical allusion for the submarine communications cable across Bass Strait from Apollo Bay, Victoria to Stanley, Tasmania.

- The name of the former Greek Royal Yacht.

- Amphitrite Pool, a shallow ceremonial pool on the grounds of the United States Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York contains a statue of Amphitrite. When First Classmen are taking their Third Mate or Third Assistant Engineer License Examinations, it is considered good luck if they bounce a coin off Amphitrite into a seashell at her feet.

Notes

- Compare the North Syrian Atargatis.

- Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 58, at Google Books

- Sel, "salt"; "...Salacia, the folds of her garment sagging with fish" (Apuleius, The Golden Ass 4.31).

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca i.2.7

- Bibliotheke i.2.2 and i.4.6.

- "...A throng of seals, the brood of lovely Halosydne." (Homer, Odyssey iv.404).

- Aelian, On Animals (12.45) ascribed to Arion a line "Music-loving dolphins, sea-nurslings of the Nereis maids divine, whom Amphitrite bore."

- Ogden, Daniel (2017). The Legend of Seleucus. Translated by Raffan, John. Cambridge University Press. p. 41, note 64. ISBN 978-1-107-16478-9.

- Wilhelm Vollmer, Wörterbuch der Mythologie, 3rd ed. 1874:

- Odyssey iv.404 (Amphitrite), and Iliad, xx.207.

- E.g. Jules Cashford, Susan C. Shelmerdine, Apostolos N. Athanassakis.

- Harrison, "Notes Archaeological and Mythological on Bacchylides"The Classical Review 12.1 (February 1898, pp. 85–86), p. 86.

- Robert Graves. The Greek Myths (1960)

- Eustathius of Thessalonica, Commentary on Odyssey 3.91.1458, line 40.

- The Wedding of Neptune and Ampitrite provided a subject to Poussin; the painting is at Philadelphia.

- ad Atlante, in Hyginus' words.

- "...qui pervagatus insulas, aliquando ad virginem pervenit, eique persuasit ut nuberet Neptuno..." Oppian's Halieutica I.383–92 is a parallel passage.

- Catasterismi, 31; Hyginus, Poetical Astronomy, ii.17, .132.

References

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Amphitri'te" , and "Halosydne.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amphitrite. |

| Look up Amphitrite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (ca 130 images of Amphitrite)